by Binyavanga Wainaina

(photographs by Philippe Niorthe)

I meet Alex at breakfast in Accra. He is a carver of wooden curios who has a small shop at the hotel. His uncle owns the hotel. He spends his days at the gym, playing soccer, and making wooden sculptures of voluptuous Ghanaian women. For tourists. He shines with beauty and health and fresh-ironedness. He seems ready, fit and ready. I am not sure what for. We chat. He doesn’t speak very much. I ask him if he can help get me somebody. He plays finger football on his mobile phone, and finds me somebody to take me to Lome.

Later, in the evening, we get in his uncles Peugeot, and he drives me to meet my guide. I am struck, again, by the fluidity of his body-language; and even more by his solemn maturity. There does not seem to be anything he cannot handle.

But – his attitude towards me is overly respectful. He plays boy to my man. Does not contradict anything I say. It is disturbing. Before we get to the suburb where his friends are hanging out, he turns to me and asks, his face awed, and suddenly boyish, “So, how is life in New York?”

We find them, Alex and me, at dusk, a group of young men sitting by the road, in track-suits and shorts and muscle tops. They are all fat free and pectoraled and look boneless, postocoital, and grey, after a vigorous exercise session at the beach, and a swim and shower. One of them has a bandage on his knee, and is limping. They are all fashionably dressed.

I ask around…they all come from middle-class families. They are all jobless, in their twenties, not hungry, cushioned in very small ways by their families, and small deals here and there.

Hubert is a talented soccer player. Twenty-one years old, he is the star of a first division team in Accra. In two weeks he will go to South Africa to try out for a major soccer team. His coach has high hopes for him.

“I am a striker.”

He looks surprisingly small for West African football player. Ghanaians are often built like American footballers. I conclude that he must be exceptionally good if he can play here with people.

“Aren’t you afraid of those giant Ghanaian players? I say, nodding my head at his hulking friends.

He just smiles. He is the one with the international offers.

Hubert agrees to take me to for a couple of days. He is mortified by my suggestion that I stay in a hotel. We will sleep in his mother’s house in Lomè. His father died recently. Hubert is in Accra because there are more opportunities in Ghana than in Togo.

“Ghana has no politics.”

I offer Alex a drink. To say thanks. We end up at a bar by the side of a road. A hundred people or so have spilled onto the road, dancing and talking rowdily and staggering. Alex looks a little more animated. They are playing Hip Life – Ghana’s version of Hip Hop, merged with High Life. It is a weekday, and it is packed with large good looking men, all in their twenties, it seems. There are very few women. We sit on one side on the road, and chat, watching people dance on the street. This could never happen in Nairobi – this level of boisterousness would be assumed to lead to chaos and anarchy, and would be clipped quickly. Three young men stagger and chase each other on the road, beers in hand – laughing loudly. Alex knows a lot of the guys here – and he joins in a little, in his solemn way.

I notice there are no broken bottles, no visible bouncer. No clues that this level of happiness ever leads to meaningful violence.

After a while, we find a table. I head off to the bar to get a round of drinks – some of Alex’s friends have joined us. (You don’t drink Guinness? They ask, shocked. Guinness is MANPOWER).

When I get back, I find a couple have joined the table. A tall man with large mobile lips and a round smooth baby’s face; and a heavily made-up young woman with sharp breasts and a shiny short dress.

The rest of the table is muted. They do not meet the woman’s eye – although she is their age. The man is in his thirties. He shouts for a waiter, who materialises. His eyes sweep around, a string of cursive question marks. People nod assent shyly. He has a French-African accent.

Alex introduces us. He is Yves, from Ivory Coast. He is staying at the same hotel that I am.

Yves laughs, his eyes teasing, “Your uncle’s hotel. Eh.”

Alex looks down. Nobody talks to me now. It is assumed Yves is my peer, and they must submit. They start to talk among themselves, and I turn to Yves.

“So – you are here on business? Do you live in Cote D’Ivoire?”

“Ah. My brother, who can live there. I live in South London. And in Chad. I also live in Accra sometimes.”

“Oh, where do you work?”

“I am in oil – we supply services to the Oil companies in Ndjamena.”

We talk. No. He talks. For a full hour. Yves is 33. He has three wives. One is the daughter of the president of Chad. The other is mixed race – a black Brit. The third lives here in Accra. I look for him to turn to cuteface by his side. He does not. And she does not react. It is as if she is worried the makeup will crack if she says anything. Every so often, he breaks from his monologue to whisper babyhoney things in her ear.

Yves knows Kofi Annan’s son. He is on a retainer for a major oil company seeking high level contacts in Africa. He looks at me, eyes dead straight and serious, and asks me about my contacts in State House. I have none to present. He laughs, generously. No problem. No problem. Kenya was stupid, he says, to go with the Chinese so easily.

This is the future. But most people do not see this…

He turns to Alex, “See this pretty boy here? I am always telling him to get himself ready. I will make it work for him….but he is lazy.”

Yves turns to the group, “You Ghana boys are lazy – you don’t want to be aggressive.”

The group is eating this up eagerly, smiling shyly and looking somewhat hangdog. The drinks flow. Cuteface now has a bottle of champagne.

Later, we stand to head back, Yves grabs Alex’s neck in a strong chokehold, “You won’t mess me in the deal, eh, my brother?”

Alex smiles sheepishly, “Ah no, Yves, I will do it, man.”

“I like you. Eh…Alex? I like you. I don’t know why, you are always promising, and nothing happens. You are lucky I like you.”

Alex looks very happy.

We separate at the hotel lift, and Yves slaps me on the back,

“ Call me, eh?”

Early the next morning, we take a car from the Accra bus rank at dawn. It is a two-hour drive to the border. You cross the border at Aflao, and you are in Lomé, the capital of Togo.

Gnassingbe Eyadema was a Kabyé, the second largest ethnic group in Togo. The Kabyé homeland around the northern city of Kara is arid and mountainous. In the first half of the twentieth century, many young Kabyé moved south to work as sharecroppers on Ewe farms. The wealthier Ewe looked down upon the Kabyé, but depended on them as labourers. Eyadema made sure to fill the military with Kabyé loyalists. It was called “The Army of Cousins” and was armed by the French.

So Eyedema had the loyalty of most Kabyé – and was happy, when threatened, to make much of the differences between the two ethnic groups. Ewe protesters were imprisoned or harassed in the 1990s. The Kabyé who were not directly related to the president benefited very little from his rule – but he held them hostage by fear. Like Kenya’s former president Daniel Arap Moi, he had so offended the rest of the country over the years, the Kabyé are terrified that if his family cease to rule, they will be victimised.

In 1974, Eyadema decided to stop calling himself Étienne. He Africanised his name, and became General Gnassingbé Eyadéma – the title “general” was not Africanised. He survived a few assassination attempts, was well known for having ‘powerful medicine’.

He threw political opponents to the crocodiles.

Lomè is hot, dry and dusty. People look dispirited and the city is rusty and peeling and bleached from too much of brine and sun and rough times. Hubert points out a tourist hotel to me. It looks like it has been closed for years – but the weather here can deteriorate things rapidly. The tourist industry collapsed after the pro-democracy riots in early 2005.

The Ewe, who are the largest ethnic group in both Ghana and Togo, settled in the Lomé area in the early 1600s. The area had plenty of trees that provided fragrant and healthful chewing sticks, traditional toothbrushes. So, it is said they called the place Alo Mé, meaning “among chewing sticks”.

For 200 years, the coastal region was a major raiding centre for Europeans in search of slaves. To Europeans, what is now Togo was known as “The Slave Coast.”

One day, some time ago, Eyadèma wrote to a Prof. Dr David Schweitzer of the Nu Health Clinic in London. The good Prof. Dr. had discovered, through his scientific research that blood cells express themselves in ‘sacred geometry and their harmonious shapes and colours.’

After he received a blood test that monitored and eliminated ‘free radicals’, Eyadema wrote to the good doctor:

‘Your contribution to humanity is greater than words can describe.’

Dr David Schweitzer is the grandson of another great contributor to humanity, Dr. Albert Schweitzer, who saved lepers in the jungle of Gabon. Prof. Dr David Schweitzer is the co-author of The Power of SuperFoods. He is the first scientist to photograph the effects of thoughts, captured in water. Prof. Dr. David Schweitzer has also discovered that disease occurs in an area of the body where cells and their molecular structures are vibrating out of harmony. He has received the World Intellectual Award from the International Biographical Center in Cambridge, UK.

He lived and worked in Lome Togo in the 1980s, where he carried out human treatment tests on Sickle Cell disease patients and Malaria patients, presumably with the approval of his friend, Eyadema.

He treated them using IUG Bio-Litho-Energies therapy, using a philpsophy called Cosmocyclic Harmonisation.

The results were spectacular.

The alchemist, Prof. Dr. Ivan U. Ghyssaert developed the Bio-Litho-Energies after 33 years researching Homeopathy, Kinesiology, and Bach Flower Essences.

BioLithoEnergies use the following: 9 colours of the rainbow (condensations of divine light), manufactured from of semi-precious stones; Dr. Ghyssaert’s Original IUG Cosmocyclic Harmonizing Drops; native metals, and wild flowers.

Other products they offer are: IUG Kenya-Aura Protection Shield, made from a meteorite found in Kenya; IUG Indigo Jojoba oil, which is endowed with finely ground diamond powder. This therapy is said to cure malaria, haemorrhoids, sickle-cell disease and help with menopause, concentration, weight reduction and breast care.

In June 2002, a BBC program, by Paul Kenyon discovered that all Prof. Dr. David Schweitzer’s qualifications were bogus.

He is not Albert Schweitzer’s son, whatever that means.

I wonder how many people died.

When Eyadema who died, while on his way to seek treatment ‘abroad’, the military forcibly installed one of his sons as president.

Faure Gnassingbe, 38 years old, the son who most resembled his father, the son known to be sober, the son who had earned an MBA at George Washington University in America before returning to Togo to manage his father’s businesses.

The Gnassingbe family are straight out of The Godfather. There are three sons who matter.

Ernest the eldest son, is a military man, his late father’s ‘enforcer’, who organised a coup in 1992, has been accused of issuing death threats to a former Prime Minister, who fled the country. He was once the Commander of the Green Berets, a Commander of a military Garrison. He organised a coup for his father in 1992. He was the favourite to take over from his father until he fell ill.

Faure managed his father’s businesses and the family interests in Phosphates, Togo’s leading foreign currency earner. He has an MBA in finance.

Rock was the rebellious one – who disapproved of his father and avoids politics, and is now in charge of the Togolese Football Federation. His brother Kpatcha used to head the state body SAZOF, which oversees investments into and exports out of the country. He is now the Defence Minister.

After Faure was installed as president by the military, there were riots in the streets, arrests, deaths; other states and ECOWAS refused to recognise his government. But his late father’s machinery organised elections, which he won. He immediately began to appeal to young people for support, saying his door was open to them.

He has had good fortune on his side: his younger brother Rock, the rebellious one, who was once a former parachute commandant, is in charge of Togolese football, and amidst all the unrest he delivered to Faure the best gift his family has received since his father took over the government in 1967.

Togo qualified for the World Cup.

They swept away a series of African soccer giants–Senegal, Mali, Congo, Zambia and Morocco – and thrilled the country. The Togolese yellow jersey is flapping about all over Lomé’s markets – like a new flag.

Rock Gnassingbe was recently made a Commander of the Order of Mono. Togo is drawn in the same group with France – an encounter many Togolese are looking forward to, especially after Senegal, who had many old grudges to settle, beat France in the opening match of the last World cup.

Hubert is not Ewe. And he supports Faure, “ He understands young people.”

It turns out that his family is originally from the North.

We take a taxi into town and drive around looking for a bureau that will change my dollars to CFA francs. One is closed. We walk into the next one. It has the characterless look of a government office. It smells of old damp cardboard. They tell us we have to wait an hour to change any money.

In the centre of the city, buildings are imposing, unfriendly and impractical. Paint has faded, plastic fittings look bleached and brittle. I have seen buildings like this before – in South African homeland capitals, in Chad and Budapest. These are buildings that international contractors build for countries eager to show how ‘modern’ they are. They are usually described as ‘ultramodern’ – and when new, they shine like the mirrored sunglasses of a presidential bodyguard. Within months, they rust and peel and crumble. I see one calledCentre des Cheques Postaux, another Centre National de Perfecionnment Professional.

There are International Bureaus of Many Incredibly Important things, and Centre’s Internationals of Even More Important Things. I count 14 buildings that have the word ‘Developpement’ on their walls. In Accra, signs are warm, quirky and humorous: Happy Day Shop, Do Life Yourself, Diplomatic Haircut.

Evereywhere.

Everywhere,

People are wearing yellow Togo team shirts.

We decide to have lunch. Hubert leads me to a small plot of land, surrounded on three sides by concrete walls. On one side of this plot, a group of women are stirring large pots. One the other, there is a makeshift thatch shade, with couches and a huge television. A fat gentleman, who looks like the owner of the place, is watching Octopussy on satellite television. There are fading murals on the walls. On one wall, there is a couple of stiff looking white people waltzing, noses facing the sky. Stiff and awkward, cliché white people. An arrow points to a violin, and another arrow points to a champagne bottle. It is an ad for a hotel: L’Hotel Climon. 12 chambres. Entièrement Climatisés. Non loin du Lycee Francaise.

One another wall, there is an ad for this restaurant.

A topless black women with spectacular breasts – large, pointy and firm – serves brochettes and a large fish on a huge platter. A black chef grins at us, with sparkling cheeks. A group of people are eating, drinking, laughing. Fluent, affluent, flexible. I order the fish.

We make our way out and look for a taxi. There are more taxis than private cars on the road. Hubert and the taxi driver have a heated discussion about prices: we leave the taxi in a huff. Hubert is furious. I remain silent – the price he quotes seemed reasonable – but Nairobi taxis are very expensive.

“ He is trying to cheat us because you are a foreigner.”

I assume the taxi driver was angry because Hubert did not want to be a good citizen and conspire with him to overcharge me. We get another taxi, and drive past more grim looking buildings. There are lots of warning signs: Interdit de…Interdit de…

One.

Interdit de Chier Ici.

A policeman stands in front of the sign, with a gun.

There are several hand-painted advertisements of women serving on things or another, topless, with the same spectacular breasts. I wonder if they are all by the same artists. Most Ghanian hand-painted murals are either barbershop signs, or hair-salon signs. Here breasts rule. Is this a Francophone thing? An Eyadema thing?

It could be that what makes Lomé look so drab is that since the troubles that sent donors away, and sent tourists away, there have not been any new buildings built to make the fading old ones less visible. The licks of paint, the gleaming automobiles of a political elite, the fluttering flags on the streets, and presidential murals; the pink and blue tourist hotels with pink and blue bikinis on the beach sipping pink and blue cocktails.

The illusions of progress no longer need to be maintained. The dictator who needed them is dead. The tourists have gone; The French are too busy Eurogising to remember Togo as well as they did.

We drive past the suburb where all the villas are, and all the embassies. Nearby there is a dual carriageway, in sober charcoal grey, better than any road I have seen so far. It cuts through bushes and gardens and vanishes into the distance. This is the road to the presidential palace that the dictator Gnassingbe Eyadema. It is miles away. It is surrounded by lush parkland, and Hubert tells me the presidential family have a zoo in the compound. Eyadema was a hunter and loved animals.

We drop off my luggage at Hubert’s home. His mother lives in a large compound in a tree-lined suburb. The bungalow is shaped like a U – and rooms open to a corridor, and face a courtyard where stools are set. His mother and sisters rush out to hug him – he is clearly a favourite. We stay for a few minutes, have some refreshments and take a taxi back to the city centre.

Driving past the city’s main hospital and I see the first signs of sensible commerce: somebody providing a useful product or service to individuals who need it. Lined along the hospital wall are second hand imported goods in this order: giant stereo speakers, some very expensive looking, a drum set, bananas, a small kiosk with a sign on its forehead: Telephon Inter-Nation, dog chains, a cluster of second-hand lawn mowers, dog chains, five or six big screen televisions, dog chains, crutches, a row of second-hand steam irons, a large faded oriental carpet.

An hour later, we reach the market in Lomé, and finally find ourselves in a functional and vibrant city. Currency dealers present themselves at the window of the car – negotiations are quick. Money changes hands – and we walk into the maze of stalls. It is hard to tell how big it is – people are milling about everywhere; there are people selling on the ground and small rickety stalls in every available space.

There are stalls selling stoves and electronic goods, and currency changers and traders from all over West Africa, and tailors and cobblers and brokers and fixers and food, and drink. Everything if fluent, everybody in perpetual negotiation, flexible and competitive. Togo’s main official export is phosphates – but it has always made its money as a free trade area, supplying traders from all over West Africa.

Markets like these have been in existence all over West Africa at least a millenium – and there are traders from seven or eight countries here. Markets in Lome are run by the famous “Mama Benz” – rich trading women who have chauffer-driven Mercedes Benz. These days, after years of economic stagnation, the Mama Benz are called Mama Opel.

Most of all the stalls are bursting with fabrics. I have never seen so many–there are shapeless sploches of colour on cloth, bold geometries on wax, hot pinks on earth brown, ululating pinstripes. There are fabrics with thousands of embroidered coin-sized holes shaped like flowers. There are fabrics that promise wealth: one stall-owner points out a strange design on a Togolese coin and shows me the same design on the fabric of an already busy shirt. There are fabrics for clinging, for flicking over a shoulder, for square shouldering, for floppy collaring, for marrying, and some must surely assure instant breakups.

We brush past clothes that lap against my ear, whispering, others lick my brow from hangers above my face.

Anywhere else in the world the fabric is secondary: it is the final architecture of the garment that makes a difference. But this is Lomé, the Freeport capital of Togo, and here it is the fabric that matters. The fabric you will buy can be sewed into a dress, a shirt, an evening outfit of headband, skirt and top in one afternoon, at no extra cost. It is all about the fabric. There are fabrics of silk, of cotton, from the Netherlands, from China, mudcloth from Mali, Kente from Northern Togo.

It is the stall selling bras that stops my forward motion. It is a tiny open-air stall – there are bras piled on a small table, bras hanging above. Years ago, I had a part-time job as a translator for some Senegalese visitors to Kenya. Two of the older women, both quite large, asked me to take them shopping for bras. We walked into shop after shop in Nairobi’s biggest mall. They probed and pulled and sighed and exclaimed – and I translated all this to the chichi young girls who looked offended that a woman of that age can ask questions about a bra that have nothing to do with it practical uses. We roamed what seemed like hours, but these Francofone women failed to find a single bra in all the shops in Sarit Centre that combined uplifting engineering with the right aesthetic.

They could not understand this Anglofone insistence on ugly bras for any woman over twenty-five with children.

Open-air bra-stalls in my country sell useful, practical white bras. All second hand. Not here. There are red strapless bras with snarling edges of black lace. I see a daffodil yellow bra with curly green leaves running along its seam. Hanging down the middle of the line is the largest feeding bra I have ever seen – white and wired and ominous – I am sure the white covers pulleys and pistons and a flying buttress or two. One red bra has bared black teeth around a nipple-sized pair of holes. Next to it is a corset in a delicate ivory colour. I did not know people still wore corsets.

A group of women start laughing. I am gaping. Anglophone. Prude.

It takes us an hour for Hubert and I to move only a hundred metres or so. Wherever I look, I am presented with goods to touch and feel. Hubert looks grim. I imitate him. Heads down, we move forward. Soon we see a stall specializing in Togo football team jerseys. There are long-sleeved yellow ones, short-sleeved ones, sleeveless ones. Shirts for kids. All of them have one name on the back: Togo’s super-striker, Emmanuel Sheyi Adebayo.

I pick out a couple of jerseys and while Hubert negotiates for them I amble over to a nearby stall. An elegant, motherly woman, an image of genuine mama-benzhood, dressed in pink lace smiles at me graciously. I am told since Eyadema died the economy has floundered in the markets, and they are now called Mama Opels. Her stall sells shirts, and looks cool and fresh. She invites me in. I come and stand under the flapping clothes to cool down. She dispatches a young man to get some cold mineral water. I admire one of the shirts – to small for you, she says sorrowfully. Suddenly I want it desperately – she is reluctant. Ok. Ok she says. I will try to help you. When are you leaving? Tomorrow I say. Ahh. I have a tailor – we will get the fabrics and sew the shirts up for you, a proper size.

It is here that my resolve cracks, that my dislike of shopping vanishes. I realize that I can settle in this cool place – cast my eyes about, express an interest and get a tailor-made solution. I point at possible fabrics she frowns and says nooooo, this one without fancy collars. We will make it simple – let the fabric speak for itself. In French this opinion sounds very authoritative. Soon I find I have ordered six shirts. A group of leather-workers present an array of handmade sandals: snakeskin, crocodile, every colour imaginable. Madam thinks the soft brown leather ones are good. She Bends one shoe thing into a circle. Nods. Good sole.

Her eyes narrow at the salesman and ask, “ How much?”

His reply elicits a shrug and a turn – she has lost interest. No value for money. Price drops. Drops again. I buy. She summons a Ghanaian cobbler, who reinforces the seams for me as I sit, glues the edges. In seconds all s ready. She looks at me with some compassion. What about something for the woman you love? I start to protest – no. No – am not into this love thing. Ahh. Compassion deepens. But the woman’s clothes! I see a purple top with a purple fur collar. A hand embroidered skirt and top of white cotton. It is clear to me that my two sisters will never be the same again if they have clothes like this.

They each get two outfits.

I can’t believe how cheap the clothes are. Now my nieces – what about Christmas presents for them? And my brother Jim? And my nephews. And what about Jim’s wife? These women in my life – they will be as gracious and powerful as this madam in pink lace – cool in the heat. Queen, princesses. Matriarchs. Mama Benzes. Sexy. I spend four hours in her stall – and spend nearly two hundred dollars.

Hubert and I make our way to a beach bar. On the way from the centre of Lomé, I see an old sign by the side of the road. Whatever it was previously advertising has rusted away.

Somebody has painted on it, in huge letters: TOGO 3 – CONGO 0.

The beach runs alongside a highway – and hundreds of scooter taxis chug past us – with 5 pm clients – mostly women, who seem very comfortable. One woman on sits the passenger seat, at a right angle to the scooter. She is holding a baby and groceries, and her head is tied into one of West Africa’s ubiquitous knots of cloth. She seems quite unbothered by the risks of two wheels. We sit on some rickety plastic chairs and discourage a guitar-playing crooner who wants to give us a personal soundtrack for sunset. We order beers.

“Look,” Hubert says, pointing at the fishermen. “They are about to pull in the nets.”

There must be fifty people all dragging one long, long net in.

“They do this every evening – then you will see people coming to buy fish for home and for the market.”

It takes at least half an hour for the net to come in. Hundreds of people gather to buy fish. The crooner returns – and a group of Sierra Leonains sitting next to us shout at him to leave.

After the sunset, we go back to Hubert’s house. His eldest brother has spent the day lying under a tree. He had a nasty motorcycle accident months ago, and his leg is in a cast. He is a mechanic and has his own workshop. His wife lives here too, and two sisters. We shake hands and he back away. There are metal roads thrust into the cast. He must be in pain. The evening is cool, and the earthen compound is large and freshly swept. It is a large old house. This is an upper-middle class family.

Hubert’s mother and sisters are happy to see him home, and have cooked a special sauce with meat and baobab leaves and chili. Hubert’s mother, a retired nurse, is a widow. Hubert is the last born, and it is clear he is the favourite of his sisters. The front of the house is rooms that open to the garden, where some of the cooking takes place to take advantage of the cool.

We all stand around the kitchen, Hubert’s brother must be thirty, but he remains sullen. Clearly they do not get along, but what is most curious is the family set-up. His mother is the head of the household. His father is dead. His brother – a good ten years older than Hubert, behaves like a boy in his presence. There is something resonant about this, and it remains in my mind…

Talking about money with Hubert has been tricky. He agreed to come with me, but said we would come to an agreement about money later. He has made it clear he will be happy with anything reasonable I can afford. He is not doing this because he is desperate for the money. He seems comfortable with the arrangement I offered– and is happy to do things trusting my good faith, and giving his. He does not eat – as an athlete he is very finicky about what he eats. I dig into the sauce. It’s hot. Awkwardly, I make him an offer.

I find out I am to sleep in his room.

It is very neat. There is a fan, which does not work. There is a computer, which does not work. There are posters of soccer players, faded posters. There are two gimmicky looking pens arranged in crisp symmetry on the table, both dead. There is a cassette player plugged, and ready to be switched on, but I can see not tapes. There is no electricity – I am using a paraffin lamp. The bedroom is all aspiration. I wonder, before I go to sleep, how his brother’s bedroom looks like.

In the morning, I try to make the bed. I lift the mattress, and see, on the corner, a heavy grey pistol, as calm and satisfied as a slug.

,,,,,

The next morning, Hubert and I head back to Accra. I do not know much more about soccer. I have a hangover. I have a very colourful new wardrobe.

I shall google.

The following description of the Kingdom of Ghana was written by Al-Bakri, a member of a prominent Spanish Arab family who lived during the 11th century.

“Among the people who follow the king’s religion only he and his heir apparent (who is the son of his sister) may wear sewn clothes. All other people wear robes of cotton, silk, or brocade, according o their means. All of them shave their beards, and women shave their heads. The king adorns himself like a woman (wearing necklaces) round his neck and (bracelets) on his forearms, and he puts on a high cap decorated with gold and wrapped in a turban of fine cotton. He sits in audience or to hear grievances against officials in a domed pavilion around which stand ten horses covered with gold-embroidered materials. Behind the king stand ten pages holding shields and swords decorated with gold, and on his right are the sons of the (vassel) kings of his country wearing splendid garments and their hair plaited with gold. The governor of the city sits on the ground before the king and around him are ministers seated likewise. At the door of the pavilion are dogs of excellent pedigree who hardly ever leave the place where the king is, guarding him. Round their necks they wear collars of gold and silver studded with a number of balls of the same metals. The audience is announced by the beating of a drum which they call duba made from a long hollow log. When the people who profess the same religion as the king approach him they fall on their knees and sprinkle dust on their head, for this is their way of greeting him. As for the Muslims, they greet him only by clapping their hands.

,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

Nearly a year has passed. The book was published.

The World Cup is over. I am in Kenya. I have spent the last week sitting on a balcony, surrounded by coconut trees and cute grey monkeys with large blue testicles, trying to write this.

I wish I had read Ahmadou Kourouma before I went to Togo.

I wish every African in the world would read Ahmadou Kourouma.

For the late Kourouma’s rage is magisterial.

Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote measures with an exactitude I have not encountered reading anything about our continent, the farce: the history, and rumour, the myth and praise, the double-eye, the flapping ears operating on four registers, the crocodile-grinning farce of the giant blue balls of our monkeyish leaders – who are rendered at once more and at once less than human by the seriousness with which their administrations took the fake independence they were given.

If it is said that Big Men survive because they cultivate mystery, readers of Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote will find themselves immune to any of the many psychological fetishes that have been ruling us. They are rendered mute by exposure.

The book is a thinly disguised attack on Eyadema’s Togo.

Here, he is called Koyaga, of the totem of the Falcon. Hunter, and Dictator-President of the Republique du Golfe. When Koyaga goes to visit his brother dictator, a thinly veiled Bokassa, of the totem of the hyena, who gives him advice:

“Other African presidents are dishonest, hypocritical. They begin the tour of their republics at the National Assembly or at some school. The most important institution in any one-party state is the prison.”

Now one of the most powerful weapons a supreme leader has is sperm. Every man spews billions of wiggly things every day. Alas, only one at a time can yield a useful son. Then here are other practicalities: money to sustain many children. Power, to keep many women and children secure and fearful. A supreme leader can ensure that he has a whole battalion of sons.

“Koyaga provides accommodation for the mothers of his children until such a time as they snare a husband capable of adequately providing for them. He finances and presides over the marriage ceremonies of his former mistresses…Former mistresses have easy access to bank credit; they end up as Benz Mummies…The administration of their allowances and the rents on the houses of his former mistresses becomes one of the most difficult duties of the republic. It is to facilitate the smooth running of this work that computing makes its first appearance in the Republique du Golfe. The task is handled by a network of five powerful computers.”

All of Koyaga’s children are educated in the School for Presidential Children. Boys are prepared to join the army. Girls marry army officers.

The Togolese soccer federation is run by Rock Gnassingbé, brother of the president and son of Eyadéma. He is also the head of the army’s artillery division.

Rock is said to be Eyadema’s most humane and compassionate son: he rebelled against his father and eldest brother.

Now soccer itself is not a negotiable object: democracy is; treasuries are; French government loans and grants; the lives of all citizens; the wombs of all women – all these things can bend comfortably to the will of the First family – but the fates of the National Soccer team belong to the people. Nobody has ever successfully banned the playing of soccer in Africa.

It is easy to see why: soccer is a skill one can cultivate to the highest levels with nothing but plastic and string and will.

A soccer player seeks to find chinks in the structural arrangements of an opposing team – needs to make his body and mind flexible; needs to have an eye that does not just understand the structure of the opposition; but can seduce, fake, deceive, con, charm. Can score, and secure victory by finding a hole, a gap, seeing avenues where zig-zag paths exist; sweet-talking your way through the barbed wire of the Port Area that serves the whole of West Africa – bullshitting your way into the Fatcats office; seducing, with a nimble tongue the stiff and proud daughter of the fatcat; and then you have access to the duty free goods of a sub-continent. Strolling through gates manned by violent giants into the inner sanctum, the president’ zoo; his home and the treasury of your country. At any time, a giant monster, or a team of them will be ready to bring you down with all the violence they know how to produce. Your tongue, the flexibility of your limbs, your sexiness, the timbre of your voice; your understanding of the structure of power you face – these are your only tools.

This intelligence is not harboured in the mind – repeated practice transfers the ideas of the mind into the instinct of the body. No gun to the head can make this body perform.

To be a successful sovereign citizen of urban Togo (or Brazil, or Nigeria, or Kenya), one who is not allied to French Scholarships and its departments; administrative authority and the ‘private sector’; one not allied by clan or tribe or family relationship to the Gnassingbés, one needs to cultivate a certain fitness; a certain rhythm – your body, your tongue must respond quickly to an environment which shifts every few minutes sometimes. Your mind must constantly invent new strategies to thrive the next day. This strategy needs to be drilled into the body, so it is used subtly and suddenly when required.

What is so sublime about the truly great soccer players is the ability of a single individual to completely bewilder a nation: Maradona over Germany and England.

Zinadene Zidane against everybody, restrained only by his own pride, his other sovereignty, his realisation at the very climax of his art and career that soccer is only a game, and he, a paid performer.

What makes billions of poor people around the world froth in the mouth about this game is that these formidable countries with their massive institutional intelligence; their media and techniques can be rendered mute by the feet of one man.

A cobbler should be able to attack you she before you see him, see a chink in your fine leather before you can slap him away. A Kenyan market trader needs to be able to pack up all wares in a minute once a City Council askari in civilian clothes has been spotted. Must do this, and turn over enough money for tomorrow’s stocks and today’s bribe, and yesterday’s children’s medication, and this months tax to a City Council that collects taxes efficiently and will never allow you to trade freely, or invest your taxes in any infrastructure for you.

A money changer standing by the side of the road needs to jostle to the front of the queue; while keeping you happy and secure; while calculating rapidly what he can offer you, which is better than what the other forty guys are shouting; must always have enough cash to handle the biggest clients, on hand.

Which braider has the fastest and most fluent fingers? How can she persuade you, as you step out of a matatu in Kenyatta market, in ten seconds, your eyes overwhelmed by screams and slogans and hands and winking eyes and jumping eye-brows, that she has the most fluent fingers?

I am sure Stephen Keshi and Emmanuel Adayebar have spent nice times in chic Lome locations hanging with The Funky Peeps: the former students of the Presidential Primary School and their now cappuccino drinking,dreadlock sporting, Paris living, liberal-talking progeny. They have sat next to each other on First class flights out of Lome; have probably screwed the same women; have invested in little deals; laughed about the now harmless and comical exploits of the “old man”; have sat on balconies in each other’s homes over barbeques and spoken with concern about ‘standards’ in their leafy suburbs.

But the World Cup is bigger than all of them; and nothing in their lives has prepared them for the scale of it; and its power.

Sides are taken.

Rock is the first to see the shit unravel. Now according to the natural law of Togo, all monies from overseas, all collected taxes, belong to the First Family. So, naturally one has to follow precedent. The FTF receives $250,000 a year from Fifa, but the 14 professional clubs get none of it. The national television station also broadcasts two live matches a week, but the clubs receive no return from that.

Forum De La Semaine, an independent newspaper in Togo accused Rock of having his hand in the till. The people of Togo are furious. The editor, Dimas Dikodo, is sweet-talked, is crocodile-grinned, offered blood-soaked sweetmeats, a lifetime of Big Man soft-brained, diplomatic visa, stiff-limbed, Euro-lubricated comfort. He says no. He is locked up.

Tino Adjeté, the football federation (FTF) treasurer, wrote an open letter, published in The Forum, to Rock Gnassingbé. He says that he cannot do his job because Rock Steady has taken sole charge of the FTF’s income and has not accounted for it.

“You are in violation of the rules of the FTF,” he wrote. “You have a duty to the statutes of Fifa. It is incumbent on us to stay credible before the rest of the world. I would like to give you the opportunity to straighten this situation out.”

The players were irate. They had asked the FTF for 2400 US dollars as living expenses for the African Cup of Nations. Commandant Rock offered them 600 dollars each. They downed tools while still preparing for the Africa Cup of Nations. The team was due to fly out to France to play a friendly against Guinea and refused to fly.

Meanwhile Rock tried to exert his power. He called a Press conference on the 14th of January to announce a sponsorship deal.

There are balloons in the Press Conference room; a few bespectacled Dutch businessmen, I imagine, one who has known and bribed and loved the Gnassingbes for forty years; and his Dutch ancestors have known and bribed fat, rich and violent warlords for a couple of hundred years – so waxy Dutch cloth, of quite astonishing expense is bought by millions of West Africans; in the room there are long, lithe hostesses serving Gnassingbe bottled water and Gnassingbe biscuits, and they are dressed in tight print fabrics and head knots that would silence Erykah Badu.

They are Mama Opels in training; in the room, there are a few sullen Eyadema Grandsons in mummy’s soft yellow skin and pouty pink lips and giant gold chains and OutKast’s wardrobe; in the room there are tight-faced fat women, still Benzing, powdered, with round surgically blanked faces; fat football officials in shoulderpadded shirts, and patrols of multi-coloured pens in their front left pockets; and right at the back of the room, standing, right in front of the red-eyed soldiers bearing guns are lean underpaid local journalists with ruled notebooks and bic pens.

International correspondents with their long Dictaphones, and dirty jeans, and 500 words before whisky, are slouched over the red velvet chairs, in the VIP section in the front, looking for The Story: the most Machetering Deathest, most Treasury Corruptest, Most Entrail-Eating Civil-Warest, Most Crocodile-Grinning Dictatorest, Most Heart-Wrenching and Genociding Pulitezerest, Most Black Big-Eyed Oxfam Child Starvingest, the Most Wild African Savages Having AIDS-Ridden Sexest With Genetically Mutilated-est Girls….

The Most Authentic Real Black Africanest story they can find for Reuters or AP, or Agence France.

But:

This time, because this is the World Cup, a billion or two viewers, and endorsements and there is a pretence that everybody comes in there somewhat equal, they will actually look for a normal story about normal human beings doing normal things. This is the only time CNN will show you a former Favela resident playing and thriving and normal and actually Speaking for Himself, and not shooting, or shooting-up, or in the throes of unbearable Care International-seeking suffering.

Sitting next to the Foreign Correspondents are their dark, slinky girlfriends, the better educated daughters of some Ma-Benzes, one of whom nearly became Miss Togo; another who nearly won her regions Face of Africa competition.

A 25 piece army band starts to play. Trumpets (The elephant is about to speak).

Rock announces that a Dutch textile company has bought the rights to print cloth with the Hawk’s logo on it. The words ‘Cloth’ and “Dutch’ are nearly as electric as the words “World Cup” in Togo.

Market women are salivating. Mercedes benz dealers start sending text messages to East London and Dusselforf.

Snap Snap. Mobile phone – motorolla razor takes a picture of the sample fabric on display. Somebody sneaks out of the room – an Ivorian perhaps, and calls his guy in Abidjan, tells him to catch a flight to the fabric factories of Ganzung Province China tonight to have five containers in Lome by the Weekend.

Tomorrow, the Chinese traders in Lome market will do the same. Cheaper.

But soccer wins over the drools of fabric.

A journalist asks Rock about the players who are holding him ransom. He loses his temper in a George-Bushish way and accuses the journalist of being unpatriotic.

Rock loses the war against error. Togo is humiliated in the Cup of Nations.

Togo meets South Korea in their opening match of the World Cup.

The entire continent, almost every man and woman – 900 million of us: in small towns in Germany where day is Euros and incontinent old Germans, and night is Neo-Nazis; in Foreign Correspondents’ Sea-Facing living rooms in Accra, long sexy limbs are flying and weave is dishevelled and a girl with a long tubular face and pouting lips is screaming, as Foreign Correspondent sips whisky and types,

“Africans in the heart of Togo’s dark jungle, in the middle of the dead animals of fetish-markets today cheered…”

“Africa forgot war and misery today, to celebrate the rare good news…”

The entire continent: in musty dormitories in Moscow; dusty and tired and drunk living among abandoned warehouses and dead industries of New Jersey; in well-oiled board-rooms in Nairobi, and Lagos and Johannesburg; in cramped tenements in the suburbs of Paris; inside the residences of the alumni of the Presidential School of Lome; in the markets of Accra, and the corrugated iron bars of Lusaka; in school halls; and social halls; in the giant markets of Addis Ababa; in ecstatic churches dancing in Uganda; on wailing coral balconies in Zanzibar; in a dark rhumba-belting, militia-ridden bar in Lubumbashi; in rickety video-shops in Dakar; in prisons in Central African republic; in mini-skirts in red-lit street corners in Cape Town, peering into SuperSport bars; in School halls in Cherengani; in Parliament cafeterias in Harare,

We all jump up and down, and shout, and sing when, in the 34th minute, Kader gives Togo the lead over South Korea, with a blistering shot from a very difficult angle.

For one and a half hours, the continent is a possible place.

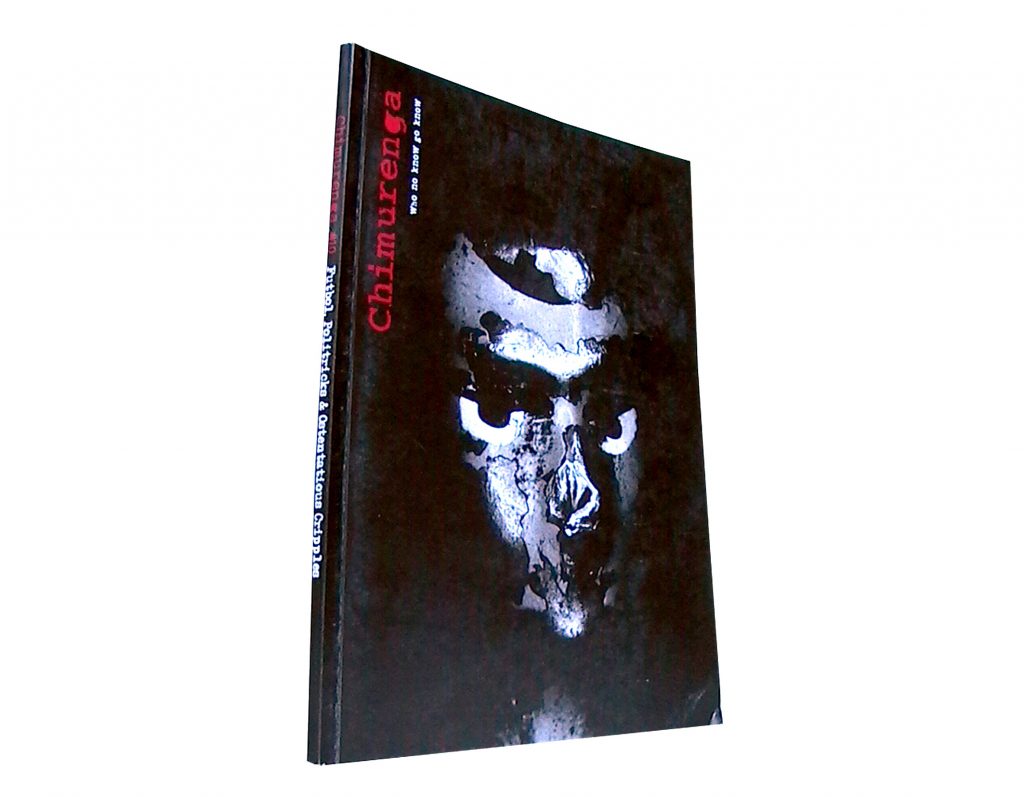

This story, and others, features in Chimurenga 10: Footbal, Politricks & Ostentatious Cripples (December 2006) in which we scope the stadia, markets, ngandas and banlieues to spotlight narratives of love, hate and the wide and deep spectrum of emotions and affiliations that the game of football generates.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work