The metronomes of ancient history, the legacy of war, the wavering prosperity of peace, impending independence and inter-ethnic tensions beat the rhythms of Juba – the new capital of Southern Sudan. Billy Kahora reports.

All day and night in July mangoes plop into the Nile flowing past Juba. Every late afternoon, Eastern European men employed by foreign contractors work out in the makeshift gym at Oasis Camp, a caravan park that’s part of the new Southern Sudan boom. Then, before the sun sets, the men congregate underneath the mango trees and shake their branches. If this fails to work, they hurl stones at any ripe colour peeping through the dark leaves. The stones fly through the branches and skim on the surface of the Nile, another fruit falls into one of their hands and they shout out in joy in their languages. The mango trees extend for tens of kilometres up and down the Nile – it is said they were planted by the British ages ago.

Downriver, in the villages, the Bari sub-tribes – on whose ancestral land Juba is located – have been eating mangoes for decades and now leave them for cattle. Or for these young Eastern European men. The local adults shun fruit trees, a new middle-class observance in this new Sudan. When the Eastern European men are not under the mango trees, they are solemn, sullen even, from heat and work exhaustion, till Juba evening comes. The afternoons are humid and hot – little work can be done and their shouts rouse everyone from their sweaty afternoon naps at Oasis Camp. The river at this time seems to be at its highest, as though rising with the sun, low in the morning, high at noon, and then low and dark in the evening.

From Nairobi, one comes into Juba by air through kilometres of variegated landscape. From the north of Kenya the world unexpectedly turns green. It is a general misconception in Kenya that north of Mount Kenya it is arid all the way to the Mediterranean; that Southern Sudan, southern Ethiopia, are all similar to the drylands of northern Kenya and southern and eastern Somalia. And so when the landscape takes to greenery brought on by the tropical belt that extends from the Congo to the West, the lush Nile Valley, and the Rift Valley, something happens to an East African consciousness. One’s ‘Kenyaness’ becomes completely discombobulated – all presumptuous ideas of the place become a new curiosity.

Juba Airport: a few kiosks, a dusty floor, all sorts of milling individuals who are clearly not travellers; the officials are half-uniformed but deadly serious about security. Like the heat in-country, Juba’s airport stupefies. There is little evidence of the usual razzmatazz of the international airport: no brand colours, tight skirted hostesses with tightly held smiles, or even weighing scales. Despite being a small, untidy space, Juba Airport remains a revolving door of international stars and continental politicians. Jimmy Carter, I am told, is always here; George Clooney passed through last week. Recently, a minister’s wife was caught trying to transport a million US dollars out of the country.

When my guide and cab driver, Shahin, picks me up, we get into the city by way of its asphalt spine. Small though, what we like to think of as an African Central Business District, Juba has a monumental ancientness to it all that is unmistakable. Bar the war, I see this as a city that was once on its way to greatness. There are the foundation stones when one finally gets to the main square from the airport. The stones are similar to those found in Nairobi’s Kenyatta Avenue, and Kampala, put down by colonial explorers, such as Samuel Baker and John Speke seeking the source of the Nile. There is also the time clock that has been counting the hours to the independence referendum.

The oldest hotel, Juba Hotel, is recognisable to subjects of the once British Empire. So too is the look of the oldest building in Juba, the British Equatorial headquarters, authoritatively familiar in its decrepit age. But with minimal tarmac, the Nile, which survived both Anyanya Wars, remains the main artery of Juba. Everything else besides the main thoroughfare is a dusty bypass connecting old neighbourhoods to war and new hope. Shahin points out the self-sufficient UN moon-base a few kilometres from the airport. Peace has also brought the housing ‘estate’ to Juba and the ‘Executive’ ex-revolutionaries have their new shiny mansionettes, wide boulevards and fledgling malls. On the other side, a large military base stands, a testament to the fact that this is all hard earned-prosperity – this was once the old airport. Dust swirls everywhere.

We head to the ministry of information where I have to report that I have entered the country as a journalist. If all else from the airport is sprawl, the new government is an immediately recognisable large block. SUVs with Government of South Sudan (GOSS) plates roll in and out – everywhere else in Juba the majority of the other cars are either UN or CD. There are queues everywhere; service is expected by the new citizenry. It is hard to distinguish between staffers and visitors: the mostly lanky dark figures all come in suits or long frocks. There is a sobriety, a freshness, even if many of the office desks are empty and people visibly loll under trees. Business is conducted on the go, in the corridors, and inside and outside cars. There are few foreigners on Government Square. Shahin tells me proudly that his sister works there.

Back at the caravan park, the Eastern Europeans workout without conversation, in grunts. Their exertion has little curiosity for other Europeans, or the locals who come in for development workshops, or the waitresses from Kenya, Uganda, Congo and Eritrea, but they attack the weights and the fruit as they would do whatever natural resource their company is extracting. The men’s day-time indifference to the waitresses is a studied casualness. One night I see one of them sneak into a caravan with one of the waitresses, a Congolese girl. They share caravans so the fellow occupant waits on the steps, a cigarette glow haloing his face.

Later, I am told that the Eastern Europeans are part of an influx that accompanies the fast track modernisation of a space that many argue has been completely innocent of wide colonial European influence since the 19th century – and now finally the UN, Western media and oil corporations and the Chinese gobble-gobble reach have arrived. And so in the caravan park, as the rest of Juba, Southern Sudan hosts an East African potpourri of Somalis, Kikuyus, Luos, Northern Ugandans, Nyankole, Bagandans, Rwandese and Borana.

The waitresses are from all over East Africa. They squabble and stride in red and black uniforms in the dust, harangue and insult each other in extreme language from boredom. Few have learnt Kiswahili and they use what they know in crudely sexual and intimate ways. They reserve their vernacular languages, Kikuyu, Chagga, Teso and Nyankole, for their tough frontier-like behaviour. When I hear two of them speak in Swahili and even later in Kikuyu, I order a meal in friendly Swahili after I have been in Juba for five days, but this is met with indifference.

The locals I see at the caravan bar are always calm, relaxed and posing after or between the innumerable workshops that are at the Oasis Caravan and all over town. Juba is in-between momentous times. A state is being talked and workshopped into being, after years of war and atrocities. Conversations around the new South Sudan hinge on the atrocities perpetrated there during the two wars; the human rights discourse professing international outrage has become mainstream. Many have argued that there are two major hurdles ahead to the proper idea of a South Sudan: rebuilding and development after all the destruction wrought by civil war, and building a commonality between the diverse peoples to which the region is home. The idea is not yet of a common peoples, whatever that means anywhere else, but something on the heels of a momentum of outrage at too much blood spilt. Even the comfort with which the East African waitresses trade insults and the Eastern Europeans eat mangoes publicly, in the presence of locals, hints that there is a commonality, a nationality that is yet to be developed.

Shahin is also a Bari patriarch – he tells me that he is expected to take care of his extended family as the oldest able man. He talks of his people proudly. Everybody else, including the Dinka and the Nuer, are foreigners, no different say, than Northern Ugandans who share a border with some of the tribes of Southern Sudan. Juba is seen as a frontier of opportunity, and it scarcely matters whether I’m as Kikuyu as that waitress, unless she can benefit from our tribal kinship. And so I am as close to her in this place as a Congolese woman. The unease of the foreigners suggests the arrogance of a newcomer to the frontier. Moreover, it stands in relief when one thinks of all the blood that has been shed here over the years. It lacks the humility of experience and carries the hubris of the profit-seeker. The waitresses serve with reluctance, their looks saying that they come from better places and have only been fooled into coming here. And now they stay for money.

Mr Singh, the Kenyan owner of Oasis Caravan Park, is one of the many who have come into the new Juba. At the end of each day, he walks around his caravan park with one of his waddling lackeys and observes the Eastern Europeans amusedly. He gives orders and his fat accountant tails him with imperceptible nods. This way, oblivious to everything, they walk around, a sure metronome, day in, day out. Mr Singh is scrawny and chirpy; he talks through the tendons in his neck as if the Juba heat has dried him out. When he is not walking before dusk, he sits in his office and makes observations about Juba to whoever will listen.

The idea for Oasis Park started across the Kenyan border in Lokichoggio, a few hundred kilometres from Juba, but closer to where we are than Kenya proper. Soon, Lokichoggio, like Nimule and other Northern Ugandan towns, will consider Juba as more of the centre than their respective national capitals. Juba certainly recognises the role Northern Ugandans played during the war. Joseph Kony’s army found itself just tens of kilometres from Juba during Northern occupation. Northern Uganda was open for all Southern Sudanese and today it is vice versa.

Mr Singh was part of a boom in the 1970s when Sudan, especially the south, imported a significant number of Kenyan goods. Back then, he says, you could go all the way to Juba from Nairobi by road. The slow strangulation of indigenous manufacturing saw the death of this trade, not to mention Anyanya 2, which kicked off in 1983. Mr Singh says he’s seen the new Juba come up in the last ten years from a spot no bigger than Lokichoggio to what it is today.

After staying two days continuously at the camp, I wake up early to head out. Breakfast here is served impossibly early. The Eastern Europeans are present, at that hour reluctant beings biting at toast and sipping, watching the waters of the Nile lap gently against its banks. One has to put in early hours before the sun really settles down. Breakfast is the most edible meal for fragile stomachs – the rest of the menu has a jumble of pseudo-Western courses, standard urban East African fare. Scrawny fried chicken with finger size fries. Some odd kind of sandwich. A string of steak. Cooking traditionally raised animal products with modern technologies obliterates most of their mass. And then, what really pays the bills here: sweating East African beers.

Shahin drives the only Toyota I see during my time in this new city. Every day he smiles quietly when I give him another new place that I want to go to, and he laughs quietly at my comments. The days are all the same, hot, dusty off the ground and with humid temperatures. And like everybody else he waits for the referendum, making as much money as possible. Unlike Nairobi cab drivers, he has the relaxed patience of a man taking to peace after years of conflict, settling into a routine that reflects his mixed priorities: cab driver, guide, part-time lawyer and Bari patriarch.

Juba is trying to revert to a glorious past: peacetime from1972 to 1983, between the two Anyanya wars. Shahin is too young to remember what it was like back then. And now, trade routes and geopolitical maps are being redrawn overnight.

“Now, everything come and go from Kampala. Khartoum now too far away. Five days by road. One week by boat,” he says. “Yes. People go by boat. Khartoum.”

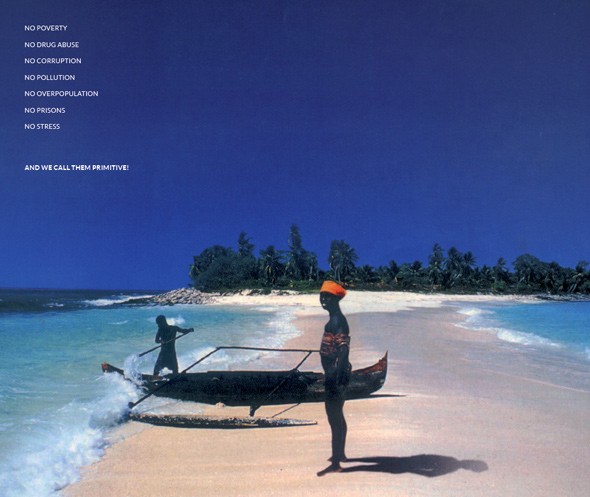

From him, it sounds like the end of the world. Juba is the new epicentre of an extremely rural south Sudan that has been in the shadow of an Arabic ‘centre’ for hundreds of years, mainly untouched by colonialism – the Brits not only ruling Khartoum from Egypt, but leaving the south as a real outpost. This has created a feeling of a new general freedom, not only from the war, but from a history of hundreds of years.

Once a settlement for soldiers returning from the Second World War who refused to go back to their village origins, Juba then became an administrative centre for the British during colonial times before 1956. Through the 1920s it had become a town for Arab traders fronted by Khartoum administrative rule. After 1972, it became a garrison town. It has always been at the centre of the Bari-speaking community’s ancestral land. Now it is the capital of what will soon be the newest African state, South Sudan.

In the 1970s, Juba was a heavily forested area – the Khartoum government cut down trees for energy and its own use. Eventually, in the 1990s, this turned out to be the only mode of survival. Because of the limited tarmac, many foolishly describe Juba as small. This is the curse and bias of urban modernity. A limited skyline blinkers horizontal vision. Juba is, however, a sprawl beyond its tarmac. A whole grass city starts with the Malakal of winding dust trails and dry streambeds that become its paths. There are several huge markets on all different points of the compass. There are feeder roads that link with the main spine that head outward to Stone Mountain, Juba University and up and down the Nile. This will all soon be connected with tarmac. There is Ghazal swamp. There is the real city beneath the modern gaze – the grass city; the UN/Donor city, and the Government city. It is said that there were only 10 cars in 2006. Now there are more than 100,000.

I meet David Ludukuu a few days after coming into Juba. Ludukuu is a UK-trained medical doctor and writer. Juba has its Shahins but it also has its Davids, a huge number of West- and East African-trained professionals returning to rebuild the new country. David tells me about macro-project stuff, the new banks, the ATMs being installed, all the architects drawing up more plans. His father never really left Juba; a civil servant during the years of peace, the older Ludukuu remained and worked for the Khartoum government in the long years of the siege. When I meet him, he tells me that nothing in Juba ever really dies, even when the new comes up. He has seen the old cattle trails fade; people barely survive on pre-modern foods, and, now, the traditional systems of power struggle for relevance in the face of the raising of a new flag, the euphoria at the end of war.

Like most of his generation, the new is not all good. There is the usual struggle for government contracts, tenders. The arrival back home of Southern Sudanese from Australia, Europe, North America and East Africa does not bring the things they learnt out there, such as democracy and professionalism. Many unfortunately align themselves with the new rulers; others aspire to be the new middle class, the backbone of any successful space. Others like Shahin look askance at these imported dreams and declare: “I am from Juba. Yes, I was born here. My family is here. No more war. I will make my life here.”

Juba also has its returning refugees. I meet a young parliamentary reporter, Luke Deng, who grew up in a refugee camp in Kenya. In a recognisably Kenyan accent he complains that in a few months millionaires have been created, but, at the same time, there are many UN drivers and night-watchmen and poor government functionaries. He laughs when I ask him about John Garang and tells me about the Garang Memorial and the false hope it now brings to its visitors. I tell him about a Sudan that is being projected as the new East African state by its media and its leadership. He looks at me blankly.

The few days I have been in Juba, I do not see any of these projections. When I listen, all I hear is Juba Arabic with its own concerns. And, of course, griping about the North and what the Arabs did. Luke shares the many conspiracies that surround Garang: how the revolutionary did not want Juba to become the capital of Sudan; his distance from the many who are now in power; how he did not want the South to separate because he believed that all of Sudan would accept him as the new leader; and his uneasy relationship with Yoweri Museveni. That is the other side of Juba and Southern Sudan, a well of secrets and conspiracies. When I ask Shahin about Garang, he smiles and shakes his head.

As we traverse Juba, through the influx of SUVs I notice a proliferation of roadside garages. Under each car or metallic shell, whole stretches of roadside earth have turned greasy. The little vegetation is dead and car parts litter the ground: crumpled oil cans, filter tins, discarded tyres, broken fenders, half engines. Greasy, streaked men wrestle with machines on jacks – GOSS and UN SUVS, metre after metre after metre. Mechanics from all over East Africa rule this part of Juba. They come from Nairobi and Kampala. There are no regular Toyota Landcruiser or Landrover dealers, but everything can be fixed here.

All these GOSS- and UN-plated vehicles are fed by the jerry-can depot near Stone Mountain. Trucks bring oil and petroleum from the newly discovered oil fields to the north. There are hundreds of yellow jerry-cans of all sizes that have been set in a winding queue. This is where Juba’s daily energy needs are distributed. There are also tankers, waiting in a large shed, that pick up diesel for industrial use and other macro needs. A pipeline is being built, but for now the operations are rudimentary. But one hears $10 billion of petroleum revenues have been consumed so far.

Juba, as is, does not even exist for East Africa. Juba, from afar in Nairobi and Kampala, is all about the resources of Southern Sudan. There is now a lot of talk of Juba as the East African community’s last and final piece of the puzzle: this new, open space that titillates all purveyors of Empire and hegemony.

The centre always overlooks what it deems as unimportant to its interests. In truth, peoples within the region have always interacted in spite of national borders. Little can be made of the differences between Northern Ugandan and Southern Sudanese peoples at the borders. And so, Juba has become a collecting point for these interlocking identities of people of different nationalities. It also carries that huge paradox of the African City and its schizophrenias.

Like borders, cities enact a similar paradox in reverse. Whereas people in borders reinforce their commonality in spite of border posts, cities carve out spaces and declare them modern, forcing people of different identities together, or forcing them to become people with a common identity. Often, in the city, the glue becomes the trappings of class. Borders separate people of similar identities. Cities become an uneasy glue of differing identities. But, Juba has now emerged as connector of different nationalities above its larger identities. Juba’s history is now being told in broad strokes – a well-known time-line that stamps authority on referendums, and shortly to follow, independence – but has yet to come to grips with the inter-ethnic tension and small ripples of attacks by locals on foreigners.

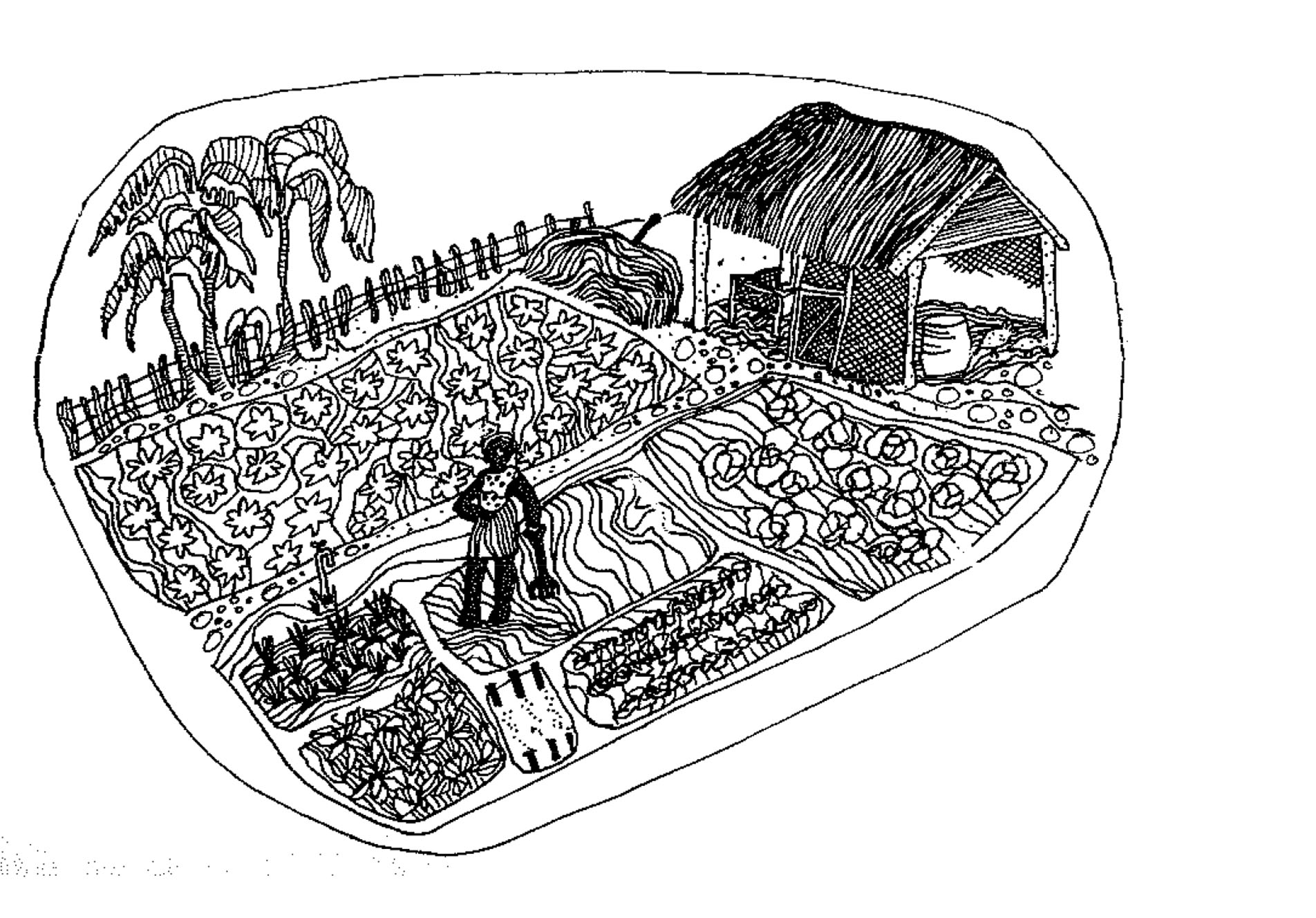

Before I leave Juba, I take a brief boat trip on the Nile. On land, Juba is too many intertwined histories of then and now, shifting geographies or tarmac and grass – a dust storm, a curfew, a heave of mass change. From the Nile it all slows down, it becomes observable, a huge cut slice. We head north first from Uganda and we see the commerce: Juba Port, restaurants, the new settlements, the old villages and then the spaces of war. On the other side we see the industries, new and old, cement and traditional practice. We see where they grow khodra and all other foodstuffs consumed in the city – this is outside of modern languages, where Juba Arabic is moving things.

A few kilometres and one enters Bari land and things have not changed for hundreds of years. Shahin seems more at ease and I remember all the things he said about being born here and living here comfortably with all the contradictions. From the Nile and in Shahin, one recognises Juba as an amazing phenomenon, a city that has the ability to integrate both a traditional past and its new oil economy on its own terms.

This story, and others, features in The Chimurenga Chronicle, a once-off edition of an imaginary newspaper which is also issue 16 of Chimurenga Magazine. Set in the week 18-24 May 2008, the Chronic imagines the newspaper as producer of time – a time-machine.

To purchase as a PDF, head to our online shop.

No comments yet.