When the Nigerian Communications Commission issued MTN, the South Africa-based multinational mobile telecommunications company, with a US$5.2 billion fine for “flouting” regulations in 2015, the global business media dismissed it as just another pitfall of doing business in Africa. Lindokuhle Nkosi goes behind the numbers to explore the “entangled steamy affairs of state and capital” that underpin economic relations, trade and diplomacy between the two African superpowers.

This is only one of many possible beginnings. An excursion perhaps, to locate where it all sparks. A strange proposal really, how the kidnapping of a Nigerian former finance minister might bring an African telecommunications giant to its knees. Drop the pin near a farm in the Akure North Council area of Ondo State, Nigeria, where seven men lie in wait on the ground, concealed by thick green braids and tangles of foliage. Some of the men have guns, handed to them just hours before; the rest carry sharpened, rusty cutlasses. The plan as conveyed to the prostrate herdsmen is to “rob a human being and sell him for money”. “How do you sell a human being for money?” Umoru Ibrahim asks himself, body flattened against the unyielding earth below him. The men move from the bush, staying low, feeling high, and enter a river near the farm, soaking themselves in the water, careful not to submerge their weaponry.

Waiting.

A Toyota Hilux passes them and drives onto the plot, its headlamps flooding them in light. The leader, a herdsman turned criminal mastermind, signals and the men crawl out of the water, silently at first, and then charging like a frenzied army. The men with guns are upfront, spraying bullets and gunpowder indiscriminately. The men behind swing knives and cutlasses wildly ahead of them. They spot the target, Chief Olu Falae, who’s celebrating his 77th birthday, and capture him.

“When we saw the chief,” explains Ibrahim, “we arrested him. One of us, with a cutlass, attacked Chief Falae and injured him. We then took him away and we had a very long walk, then Baba Uro showed up with a bike. He and one other mounted the bike and they took Chief away.”

The rest of the men walk 12 hours through light and dark before reaching the meeting point, where the chief sits bound, blood trickling from his head. They stand watch over the former minister for four days, until a ransom is negotiated and paid. “We got a call that the ransom had been paid and we should let him go. We took him out on the road and we all fled.”

This piece appears in the Chronic, April 2016.

On 14 October 2015, the police receive a distress call from a bank that’s currently being robbed. After a pursuit and a shootout, the robbers are caught with N137 million, an AK-47, a rocket, a pistol and six magazines in their possession. Some of the notes are marked, the same cash that was paid by Nigeria’s intelligence 24 days ago during the ransom negotiations for Chief Olu Falae.

In a time of Boko Haram, the kidnapping dominates the headlines. The tabloids scream: “Christian Yoruba Chief Kidnapped by Muslim Fulani Herdsmen”. It has all the makings of a perfect scandal: tribal and ethnic conflicts, Christian Big Men and Muslim protagonists, North vs South Nigeria politics, crime and money. Something has happened here, but you’re not sure what it is. You read the evidence, pick at the facts as one would in a crime novel, but somewhere along the line, criminals morph from a crew of naive herdsmen into Africa’s largest mobile network operator. The tribes are nation-states – Nigeria and South Africa. The entangled, steamy affairs of state and capital. And a ransom that has ballooned from N5 million, bound and packaged in bags, to a fine of US$5.2 billion; the largest in Nigeria’s history. So, how do you sell a human being for money?

***

When creating an African multinational corporation, you must be brave, ready to take risks, and unscrupulous. The “Rainbow Nation” will be your guiding force, and if Mandela is with you, what weapon formed against you shall prosper? These are the new economics; South Africa is sanctionless. The gates in the global economic wall have crumbled like the Berlin Wall and there’s all this money to be made, wealth to be had. Let’s not talk reparations, wealth redistribution and land reform, structural inequity. And there’s no use mentioning the trillions that disappeared from the Reserve Bank during the transition to democracy. We’re free goddammit! The invisible hand of the free market is reaching out to you South Africa! Grab it with both hands. We have acronyms and abbreviations: RDP and OPEC, OBE and AA, BEE and BB-BEE. We have board members with struggle credentials. Trade unionists turned capitalists. We have blood just waiting to be turned into gold. It’s 1994, and we have alchemists.

Start where you are. Post-apartheid South Africa. Incorporate what will become a multinational telecommunications company. Fill the board with fresh-faced businesspeople with worldly accents and international degrees. A few of them must be politically connected. Be down with the people but have friends in high places. Expand. Cross the Pongola River. Paint the Swaziland borders yellow (Yello Summer). Go to Uganda, Rwanda, Cameroon… And, as any business knows, go to Nigeria.

It’s an obvious proposal. One hundred and twenty million people. Africa’s largest consumer base, its largest economy. They say: if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere. But Nigeria is particular. Market observers call it “extremely risky”; its economic and political tectonic plates are always shifting, rubbing against each other, erupting. There’s the unstable power supply, a lack of infrastructure and inconsistent government policies. Add to that Nitel, the parastatal that had been governing telecoms in the country. In the decades it has been operational, it has only amassed a few hundred users.

But you’ve done this before, perfected the strategy in South Africa. Build the infrastructure, make friends with the state. Outspend your competitors. Tint everything yellow, and use money to tilt the odds in your favour. Bend a few rules, but keep the rule-makers happy. Read Peter Enahoro’s How to be a Nigerian.

***

Fifteen years: how long MTN has been operational in Nigeria. The registration process too was long: six years; five court edicts; two presidents.

Almost sixty-three million – the number of subscribers on the network in Nigeria. MTN is the market leader, surpassing Globacom (31.3 million), Airtel Nigeria (28.6 million) and Etisalat (22.9 million). MTN’s consumer base in Nigeria is more than double its base in South Africa.

US$5.2 billion – the original MTN fine, issued on 25 October 2015. The Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) has sanctioned MTN for “flouting” regulations. The telecommunications company failed to register all SIM cards in operation. Because of this failure, the NCC required that all unregistered or improperly registered SIM cards be disconnected from the network. MTN again failed to act. This is the biggest sanction ever issued by the NCC, and is also one of largest in Nigeria’s history, even larger than the fines paid by Shell for polluting the Delta region.

Twenty-five – the percentage decrease in the fine. The decrease was initially thought to be 35 per cent. This would bring the fine down to US$3.4 billion. The NCC alleges that this was a “typo”.

US$3.9 billion – the final MTN fine.

***

You’ve dug up all the required documents: ID book. Check. Your signed lease as proof of address. Check. A passport-sized photo: colour, no smiles, no headgear, perfect lighting. You know this because you’ve done this before. Stood in this queue, with the exact same documents, two years ago. But for some reason you have to do it again.

Yesterday you arrived at the MTN centre at Ile-Ife at 10.30am. You were number 333 in the line. Today, you’re a little smarter, a lot earlier. You wake up with the sun. Your geyser has stopped working. The light on it blinks red, but the water runs cold. You heat a large pot of water in the kettle and pour some out into a cup for tea, the rest goes into a red bucket in the shower. You wash, get dressed, double-check your documents. You’re at the MTN office at 7.30am. You are number 100. Around the corner, three entrepreneurial boys, maybe 15 years old, sell “pre-registered” SIM cards.

In the queue, people complain loudly. They’re supposed to be at work. They’ve travelled two hours, or they’ve waited for 12. The machines have stopped working. The internet is down. At midday only four people have been successfully registered, but in a network audit a few months later, the NCC discovers some strange registered subscribers. You haven’t managed to register your SIM card, but a goat named Mohammed and numerous yams from around the country have.

Your line is disconnected.

***

When Chief Ole Falae arrives at the Special Anti-Robbery Squad premises in Ondo State, he is greeted by applause and cheers. In a line-up he points out Umoru Ibrahim and Idris Lawan, two of the men who held him captive in the bush, threatening him every hour for four days.

“This one,” he says, fingering Ibrahim, “threatened to shoot me.”

Another suspect, Dojijo, denied taking part in the kidnapping. “I wasn’t involved in it,” asserts Dojijo. “Though my phone number was used for the negotiation of the ransom and a large amount of the ransom was found on me, I wasn’t involved.” Dojijo claims that his friend, Idris, borrowed his MTN SIM card over a period of four days. And that Idris returned it, two days after Sallah, with a bag containing money. “As soon as I put the SIM card back in my phone, the police arrived and arrested me.”

***

In May 2013, as part of its counter-insurgency operations against Boko Haram, the Nigerian military shut down mobile GSM services in three north-eastern states – Adamawa, Borna and Yobe. While they released few official public statements, the spokesperson of the 7-division of the Nigeria army, Col. Muhammed Dole, confirmed that this strategy was an attempt to slow down the communications of Boko Haram operatives, who were spread out in camps. All four national carrier services were barred. Troops arrived in Borno State capital by land and air. Jet fighters were spotted overhead. A state of emergency was declared. Schools closed.

Services were shut down again in March 2014.

***

MTN takes the NCC to court over the fine, essentially asking a Nigerian court to challenge its own regulations. To decide between state and capital, as though the distinction were real. The court washes its hands of the matter, urging MTN and the NCC to seek an “amicable” out-of-court settlement. MTN hires a former US state attorney to represent it in court.

In 2013, the NCC issues a first round of fines and deadlines to mobile operators, at a combined total of N53.8 million. At this stage, the fine given to MTN is N29.2 million: N200,000 per 146 pre-registered SIM cards reported to the commission.

In 2015, the NCC announces a second process of re-registration, sparking rumours that the regulators have misplaced the original data. The NCC argues that 38.87 million users have not registered correctly. Fingerprints were poorly taken, photographs were blurry, some proofs of addresses were faked.

On 4 August 2015, the NCC meets with representatives from all four mobile network operators to discuss the security challenges presented through the use of pre-registered, unregistered and incorrectly registered SIM cards. The operators are presented with an ultimatum: all problematic SIM cards within seven days.

On 14 August 2015, an audit is conducted. While the three other operators have begun to deregister problematic SIM cards, MTN had shown “no signs of compliance”. MTN is fined N102.2 million, Globacom N7.4 million, Etisalat N7 million and Airtel N3.8 million. The other operators have complied, they have paid up and deregistered SIM cards, while MTN has left 5.2 million “improperly registered” users still active on their network.

On 20 October 2015, MTN is sanctioned to pay a sum of N200,000 for each of the 5.2 million improperly registered SIM cards, totalling N780 billion.

On 2 November 2015, MTN renews its license to operate in Nigeria until 2021.

On 2 December 2015, MTN announces that the NCC has reduced the fine by 35 per cent.

On 3 December 2015, the NCC announces that its earlier missive to MTN contained a typo. The fine is actually reduced by 25 per cent. The amount drops to US$3.9 billion, payable on 31 December 2015.

On 15 December 2015, MTN challenges the fine in court.

On 7 January 2016, MTN acquires Visafone, the only surviving Code Division Multiple Access Network (CDMA) in Nigeria’s telecommunications industry. Amina Oyagbola, an MTN executive, says the acquisition of Visafone is in line with a continued commitment by MTN to improving the quality of its broadband services.

***

Some economists call the fine “an elaborate 419 scam”; extortion at the hands of an unscrupulous government; a pitfall of doing business in Africa; a misguided campaign to eradicate corruption; Buhari is showing up and showing off; Nigeria is biting the hand that feeds it; Nigeria is running out of oil, running low on reserves. Others think the fine is well deserved, that MTN has a history, widely reported, of playing fast and loose with results and a cavalier attitude to regulations and conventions. This liberal adherence to the rules is part of the reason for MTN’s success. Rules are for other people, with less money.

In Nigeria, the NCC edicts have real-life effects: money and queues and inconvenience and disconnected phone lines. Broadly, opinion in the Nigerian press falls under two categories: it’s a matter of surveillance and personal privacy – the government is using the threat of Boko Haram and terrorism as an excuse to spy on its citizens; or, it’s typical of South Africa, even its companies feel like they are above the law.

***

The Johannesburg Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) takes place in early December 2015, under the theme “Africa-China Progressing Together: Win-Win Cooperation for Common Development”. President Jacob Zuma’s opening speech contains all the accurate keywords: development, infrastructure, poverty eradication. President Zuma says that the conference “offers a unique opportunity to reiterate the historical friendship between 2.3 billion people of Africa and China. It is also a partnership anchored in equality and respect, and aimed at improving the lives of a substantial portion of humanity. It is also an opportunity to further harness and complement the economic potential of two of the fastest-growing regions of the world.

“Reflecting on the mutually beneficial results that FOCAC has achieved since its inception 15 years ago, my Government and I are convinced that the Johannesburg FOCAC Summit will further afford us an opportunity to continue to strengthen the current platform for collective dialogue, consolidate Africa-China traditional friendship, deepen strategic collaboration and enhance the mechanism of practical cooperation between China and Africa.”

It’s against this backdrop of China-Africa economics, cooperation and friendship that Zuma and Buhari are rumoured to meet. The leaders need to talk about another relationship – their own. South Africa and Nigeria have long been jostling for pole position in the African Success Story, and this is not without its tensions. For years under apartheid, Nigeria was the undisputed superpower below the Sahara. South Africa didn’t even exist. When Nelson Mandela campaigned against Sani Abacha’s government and its execution of the Ogoni 9, Abacha felt slighted. Nigeria supported South Africa’s liberation struggle – it sanctioned the apartheid government and opened its borders and resources to South Africans seeking refuge, and so Mandela’s outspokenness felt like a betrayal. Former president Thabo Mbeki traces the diplomatic anxieties between South Africa and Nigeria to this moment.

“President Mandela came under great pressure publicly to condemn the Nigerian Abacha military government, especially for its continued detention of M.K.O. Abiola who had won the 1993 Presidential elections, and agree to the imposition of some sanctions against Nigeria,” Mbeki recounts in a statement released on his Facebook page in February 2016.

“In July 1995 I led a small delegation of our Government to Nigeria to meet General Abacha. This time our focus was on the two matters of persuading General Abacha and his Government to release the Ogoni leader, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and his co-accused, as well as to release Generals Olusegun Obasanjo and Shehu Yar’ Adua… Having heard us out, he told us that he would reflect on what we had said and would respond to us before we left Nigeria…”

“This response was that with regard to the matter of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his co-accused, Gen. Abacha could not intervene to stop a legal judicial process which involved murder charges. However, if the accused were to be found guilty and sentenced to death, he would use his prerogative as Head of State to reprieve the accused so that they would not be executed…”

“It was with this knowledge that President Mandela left South Africa to attend the New Zealand Commonwealth Heads of Governemnt Meeting. When Ken Saro-Wiwa and others were executed, President Mandela was truly surprised and genuinely outraged that Gen Abacha could evidently so easily betray his solemn undertaking in this regard. Undoubtedly our Government drew its own conclusions from this painful experience with regard to the complexities of the construction of inter-state relations, including as this relates to the effective promotion of human rights.”

When Mbeki and Obasanjo took their respective seats as first citizens of their countries in 1999, they made efforts to mend this rift. Together, they spearheaded the formation of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the African Union (AU) and the South Africa-Nigeria Binational Commission. When Jacob Zuma and Alhaji Umayu Yar’Adua took over, they were prepared to maintain the close ties.

But there were issues: the 125 Nigerian nationals who had been refused entry into South Africa in 2010 and the 125 South Africans who had been deported in retaliation; Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s appointment as chair of the AU after South Africa and Nigeria had both agreed that neither country would run for the position; and the brutal xenophobic attacks in South Africa, in 2008 and again in 2014.

Both presidents know that this is a diplomatic issue. Everything that happens involving South Africa and Nigeria is a diplomatic issue. The NCC protests, “This has nothing to do with Buhari”, but the rumours persist. Nigeria’s president of “No tolerance corruption” and South Africa’s president of “Corruption? What corruption?” need to negotiate this US$5.2 billion fine.

Neither president openly discusses the fine.

A week later, the fine is reduced.

According to security analysts, a key to Boko Haram’s success is its ability to coordinate operations and cells across spatially remote locations. Also, Boko Haram mutates quickly, adapting to “tactical exigencies on the ground”.

Outside of credible human intelligence, Nigerian security agencies are reliant on tapping the phone lines of suspected Boko Haram members and their funders.

Step 1: Seize control of the 150 million active phone lines in the interests of “enhancing the security of the state”.

A number of Boko Haram leaders are arrested. In response, Boko Haram embarks on a series of attacks on telecommunications bases in Borno, Yobe, Bauchi and Kano. Abi Qaqa, the Boko Haram spokesman, has this to say: “We are attacking GSM companies because they have helped security agencies to arrest and kill many of our members and we will continue our attacks on them until they stop.”

***

To register a SIM card, a user must provide, in addition to fingerprints and other biometric information, their mother’s user name. Currently, Nigeria has no legislation or infrastructure in place covering personal data protection. The constitution states that “the privacy of citizens, their homes, correspondence, telephone conversations and telegraphic communications is hereby guaranteed and protected”.

***

Sifiso Dabengwa, the group CEO of MTN sits across from his predecessor at the latter’s air-conditioned office, shifting uneasily in his chair. Dabengwa has been summoned from the sprawling estate in Roodepoort, Johannesburg, where MTN is headquartered, to Phuthuma Nhleko’s investment company in Sandton. Nhleko was at the helm when MTN entered the Nigerian market. Dabengwa has served as both CEO of the group and CEO of its Nigerian operations.

Perhaps Dabengwa argues the simple economics. Argues that this is a balancing act to mitigate a bleeding Nigerian fiscus. Maybe he mentions all the other fines paid by MTN in that year; the N21.8 million for the sale of pre-registered SIM cards, or the N80.4 million for the failure to deactivate 420 MSISDN (landline telephone numbers linked to SIM cards). The regulator has issued MTN with more “notices of intention to sanction”: one to do with the depletion of data bundles, and another relating to the portability of cell phone numbers.

Does Dabengwa argue that this is a witch-hunt? Does he insist that MTN is the victim of a complicated shakedown? Nhleko is sympathetic but unmoved. The shareholders need accountability, the stock market demands action. Dabengwa steps down, stating, “Due to the most unfortunate prevailing circumstances occurring at MTN Nigeria, I, in the interest of the company and its shareholders, have tendered my resignation with immediate effect.”

Nhleko is now group CEO again, albeit temporarily. A month later, in the first week of December 2015, MTN Nigeria’s CEO, Micheal Ikpoki, resigns, taking the head of Regulatory and Corporate Affairs, Akinwale Goodluck, with him.

***

Meanwhile, according to the Financial Times, Nigeria has applied for emergency loans from the World Bank and the African Development Bank to the value of US$3.5 billion, roughly the equivalent of the MTN fine. Kemi Adeosun, the finance minister, denies this, stating that “no formal loan applications have been made”, and that Nigeria as a member of the World Bank group “is entitled to access available funds like every member-country”.

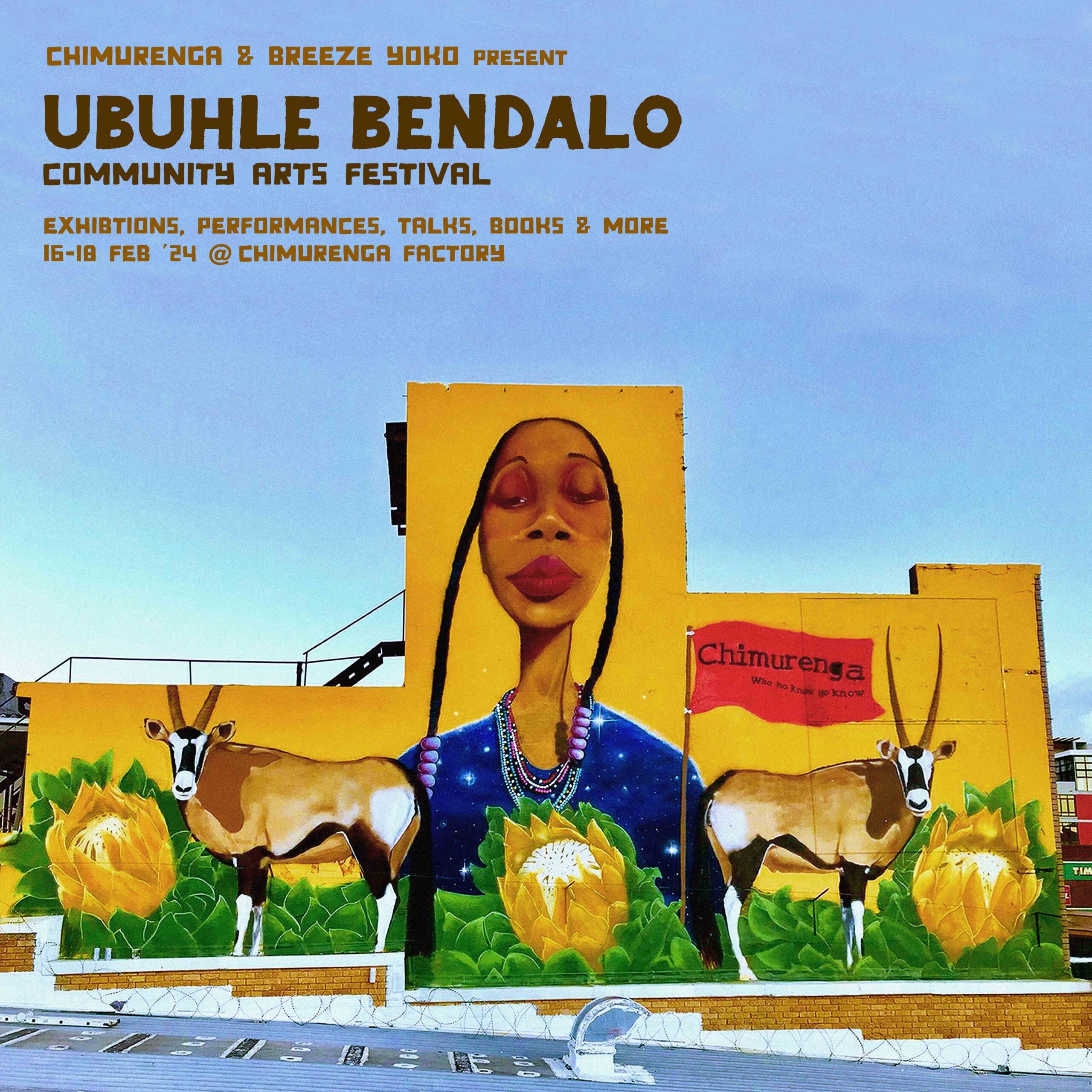

This story features in the Chronic (April 2016), an edition in which we explore the tensions between reform and revolution, and decolonisation and the neoliberal order in the academy, through the lens of history and via the alternate education paradigms based in indigenous knowledge systems, and also arising from South Africa’s radical anti-apartheid struggle.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

No comments yet.