Akin Adesokan writes in exaltation of the game of tennis, the sheer artistry of arguably its greatest and most storied male player and his 24 tricks of the forehand.

With his second-round loss to an unknown Ukrainian player in this year’s Wimbledon, tennis great Roger Federer missed reaching the quarter-finals of a grand slam event for the first time since the 2004 French Open. Federer, the defending champion, fell to Sergiy Stakhovsky 7-6, 6-7, 5-7, 6-7 on Wednesday, 26 June 2013. Unable to defend his title, the former No. 1 fell to No. 5 in the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) rankings on 8 July, his lowest since 2003.

It was a stunner. Here was the one and only Roger Federer, arguably the greatest male player of all time, winner of 17 grand slams and 79 tournaments in total, with the highest number of weeks at No. 1 in the ATP’s rankings, being routed by a journeyman ranked 116th. The event quickly overshadowed the upset of the previous day, when Rafael Nadal, two-time Wimbledon champion, crashed out in the early rounds for the second straight year. The previous week, Roger had won the Gerry Weber Open in Halle, Germany, but it was small consolation. He had reached the finals of only one tennis event all year – the Masters in Rome – and that he lost to Nadal. Finally, improbably, he crashed out of the Wimbledon he was favoured 9-1 to win.

It was beginning to look like the twilight of the god.

Before Wimbledon, tensions were running high. You can have the best game in a sport, be its most storied player, but if you are not reaching the finals and winning them, particularly in a manner your fans are accustomed to, things are bound to get anxious. I was feeling the heat on Sunday, 17 June, hours before Roger beat Russian Mikhail Youzhny at the last grass-court event before Wimbledon.

Until Roger rose to the top, I never cared much for the career of a single tennis superstar. I liked Boris Becker in his prime, but viewed him as distant and ancient. I admired the Williams sisters and liked to see either or both of them win. When they played each other, I rooted for Venus, who had more grace on court. But there was something insincerely infantile in the way Andre Agassi broke into tears and piled his hands on his head after every win. Martina Hingis came across as a mean-spirited sore loser. It was enough to know that Pete Sampras was a Florida Republican for him not to have my sympathies, win or lose.

With Roger, it is different. I am happy each time he wins a match. I am sad each time he loses. Once he is eliminated from any event, my interest wanes. I would still watch the remaining matches, but there is no one left to root for.

I am not a tennis player myself, so what does this deep identification with the game’s most storied player mean for me? Tennis is not a team sport, my interest cannot be of the Nigerian Super Eagles variety, generated by the patriotic fervour of seeing one’s country’s representatives triumph. For this, one need not know anything about the game; patriotic opinionating is all that matters.

Could it be a matter of colour? With the ascendancy of the Williams sisters, the game certainly received the kind of racial-uplift boost it did not have with names like Arthur Ashe, MaliVai Washington, and James Blake. But when Roger is facing black players like Jo-Wilfred Tsonga or Gaël Monfils or even Blake, there is never a question of where my allegiance lies. Politically also, my sympathies are always with the underdog in any contest, so the instinctual allegiance to the top dog is out of character.

American writer David Foster, himself a tennis player, described watching Federer play as a “religious experience”. In analysing my feelings, I have often wondered if my secular devotion to Roger’s fortunes is a way of making up for the lack of religious devotion in my normal life.

Talent the man has in ample, demonstrable quantities. The sheer beauty of his movements – the effortless manner in which he plays the game – has precedence perhaps in the career of the Australian legend, Rod Laver. Talent is an endowment of quality, and if one has that endowment in great quantities, it is but a short stretch before the possessor attains the status of genius. This is the distinguishing mark of Roger as a tennis player. He plays the game at the highest level, displaying unusual skill and intuition, and enjoying every bit of his time on court.

It is 4 July, 2004. Roger is playing against Andy Roddick, ranked number two and then current US Open champion, in the Wimbledon final. Having won Wimbledon for the first time the previous year, beating Roddick in the semis, and also taking the Australian Open in January, Roger is at the top of his game. He will end the year with a phenomenal 76-6 record of games won and lost. After the semi-final victory, the former tennis player, Mary Carrillo, running commentary for NBC, says of Roger’s game: “This is masterful. This is the kind of tennis that wins Wimbledon.”

And so it was, as Mark Philippoussis found out two days later.

Andy Roddick – the 21-year-old golden boy of American tennis, who has unquestionably the fastest serve in the world, peaking at 234kph – is similarly high-flying and highly regarded. He is ready and able to match Roger, point for point.

True enough, serving at 30-40 in the third game at 1-all, Roger hits a second-serve return with a weak forehand slice that the opponent pounces upon for a clear winner. Roddick’s game relies on the power of his incredible serve, and the way he paces it to outwit Roger’s nimble footwork. The first break thus goes to Roddick, who holds serve on the next game and never gives Roger a chance, winning the first set 6-4.

This is the kind of challenge Roger needs. While facing the Australian top player, Lleyton Hewitt in the quarter-finals, the loss of a service game sufficiently energised him to come back with an angry resolve, breaking all of Hewitt’s serves and routing him in straight sets. In the second set against Roddick, then, Roger races to a 4-0 lead before being broken on his third service game. But no matter: even though his serve lets him down consistently in this set, such that Roddick actually pulls up to a 4-all tie, Roger has the match pretty much in control, through an ingenious plan involving the mixture of serve-and-volley and his magical forehand dexterity. Here is how it happens.

According to the tennis analyst, John Yandell, who has pulled together a broad array of videos of Roger’s games, a careful attention to his forehand shows a flexibility that is not only unprecedented, but also previously considered impossible in tennis. Using slow motion and an impressive assuredness, Yandell has demonstrated that Roger has no fewer than 24 ways of hitting a forehand.

“Federer has found ways to combine the velocity associated with the classical style,” he writes, “with the heavy spin associated with the extreme styles. And to create virtually any variation in between.” His forehand “synthesises elements from technical styles that previously seemed incompatible.” Getting even more technical, but with great assurance, Yandell notes that Roger’s forehand

is classic in the sense that he has a conservative grip structure, somewhere between a modern eastern and a mild semi-western. This grip makes it possible for him to hit on the rise, and also to step into the ball and hit effortlessly with a neutral stance and a vertical finish. But his forehand is also extreme. It incorporates the patterns of extreme torso rotation and extreme hand and arm rotation associated with the underneath grip styles.

How does one play against someone with this range of skills in using just the forehand? When writers like Wallace and Calvin Tomkins say that Roger makes shots that no pro tennis player has ever tried, this is what they are referring to.

He racks it up in this second set. More than once in a quick succession of the next four games, Roger relies on the diverse tricks of the forehand, not needing to use all two dozen of them. He is serving after Roddick has held for 4-all and without a moment’s notice, changes tactics. He watches the ball sail close, holds it for a few seconds more than necessary, and this is possible because he has created an extra leeway for himself by retreating just a little to the baseline. Meanwhile, Roddick, expecting a quick return, has committed to a direction, turning to his left because that is the way Roger is looking as the ball makes contact with his racket. But those few extra seconds are now lots of time for Roger, and he puts the ball to Roddick’s right for a winner and a hold for 5-4.

He uses the same tactic in the next game, on Roddick’s serve, but this time with another unexpected change in the middle of play. He is deploying lots of volleys and also mixing them with net plays. He manages to push the man to two deuces before Roddick’s explosive serves produce two consecutive aces to win the game. No matter, still: he will win the next two games and take the set at 7-5. He has executed his plan without seeming to have developed one, and it consists of slowing things down, out-thinking the opponent and forcing a change of course that the latter isn’t prepared for.

When using the backhand (“a thing of beauty” according to Tomkins), Roger is a delight to watch. Study any picture of him taken as he tries to return a shot. You will see that his eyes appear shut, that his left hand is just an inch below the yellow sphere, and that the right, yes, the racquet, is also an inch below the ball, ready for a fluid stroke of one-handed backhand. But in reality, the eyes only narrow to keep the ball in view, and the appearance of being closed is a sign of intense concentration.

The third set is now at 2-1 in Roddick’s favour, and the backhand comes in handy, when the aces are slow in coming. He continues to wrong-foot Roddick with the backhand slices, especially during the long rallies with the fast-serving American. It is hard to be distracted from a beautiful sight, particularly when it is producing desired results.

So I find myself writing about Roger, not only as a way of better understanding the game of tennis as a vector of individual excellence, but also for what it might reveal to me about the profession of writing. Some of the game’s elements – individual effort, discipline, luck, chance – are also at play in writing. A writer can think of teamwork in marketing a book, not in writing it. In tennis, as in golf, you are as much on your own as a writer is before the blank sheet or the blank screen, and are, ethically speaking, ruled out of appealing to the practice of equal opportunity.

It is true that the level at which professional tennis is played, with the multi-million-dollar prize money, the endorsements, the prime-time exposures, and the year-round tours, is one of extreme prestige (and risk) and commercialisation, and leagues away from the world of the kind of monkish dedication to figurative language that I have come to understand as writing. It is also true that authors of books that sell like Nike shoes (Dan Brown and JK Rowling, for example) are regarded as celebrities in the manner of top-ranked tennis professionals. But this is not what is on my mind when I contemplate Roger’s career.

Roger does not have – or at any rate does not reveal – the neurotic, self-destructive habits of sports superstars as gamesmen or celebrities. He plays with amazing grace and elegance, and only in his pre-junior phase was he known to throw tantrums or destroy his racquets out of frustration.

The third set is at 2-1 in Roddick’s favour when Roger, serving at 40-0, produces a rare 210kph serve, forcing an even rarer “C’mon!” from himself, the resulting energy solid enough to power him to win three straight games. He loses only one service game after that, but he will win the set again, in tie-break. So it is not so much the serves, which continue to middle at around 60 per cent on first and second, that do the trick. It is the returns on forehand or backhand, calling upon those 24 odd variations, which allow Federer to fight from behind and neutralise Roddick’s improbable serve – the serve that wins him an endorsement from Microsoft Windows. By the eighth game in the set, winning which gives Federer a 5-3 edge, Roddick has won 11 of 12 points, and the next game looks like it is the last. No matter, let Roddick take that. The aces are now back and Federer reaps one on a 206kph first serve, watches his now-tired opponent commit an error on the next point, before hitting a characteristic wrong-footing backhand winner for a 40-30 championship point.

The next sound is that of an ace and an emotional breakdown on grass. Roger has successfully defended his title at Wimbledon, and he will continue to do so year after year, and not just at Wimbledon. By now, he is no longer “the finest player of his generation,” as John McEnroe puts it in 2005, but the best player of all time.

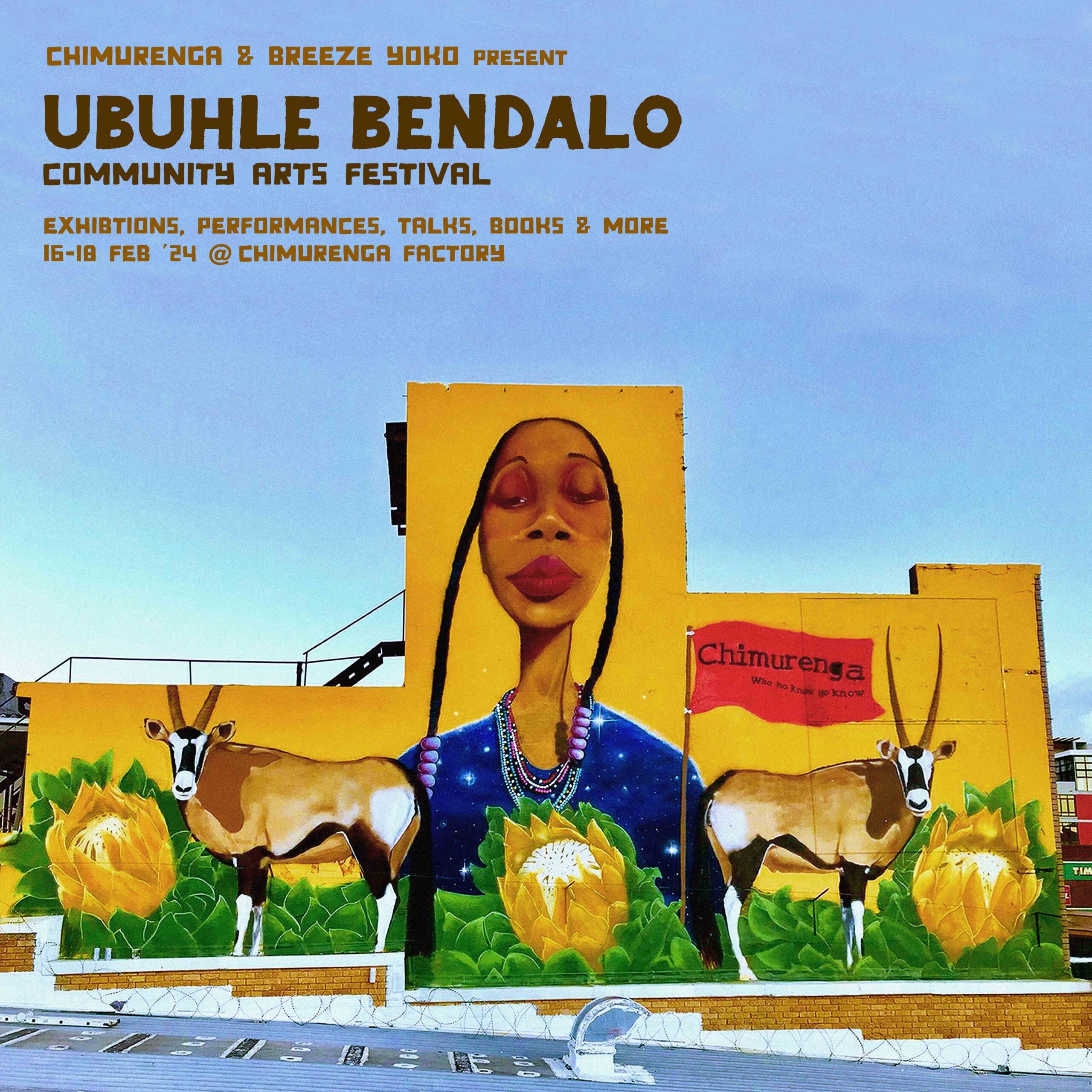

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

In this issue, artists and writer from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states. To read the article in full get a copy in our online shop or visit your nearest stockists.

Buy the Chronic

Buy the Chronic

No comments yet.