By Simon Kuper

Every year, in an election you may have missed, Belgian football coaches and journalists vote for the best African player in the Belgian league. The most recent “Ebony Shoe” went to the Senegalese striker, Mbaye Leye, prompting a worldwide chorus of “Who?”

If you scan the list of previous winners of the award (and forget the colonialist overtones of its name), you see some rather more prominent players. In 2004 and 2005 the Ebony Shoe went to Vincent Kompany – the captain of Belgium and Manchester City – who is of Congolese descent (his surname refers to the old, colonial Belgian ‘company’ in the Congo for which an ancestor worked). A fellow Belgian of Congolese origin, the striker Romelu Lukaku, soon perhaps of Chelsea, won in 2011. And in 2008 the prize went to the Belgian-Moroccan, Marouane Fellaini, now of Everton, soon perhaps of Manchester United. A scary thought: perhaps the best ‘African’ players aren’t Africans at all, but rather Europeans of African origin.

Sportsmen born in Africa are born with a disadvantage. In our book, Soccernomics, the sports economist Stefan Szymanski and I stated a general rule of sport: poor countries are usually poor at sport. The few black African champions in international sport have been, for the most part, Kenyan and Ethiopian distance-runners – and running is probably the sport that typically requires the least resources. You don’t even need a pair of shoes. But looking at international triumphs across all sports, 4.3 million white South Africans have outcompeted the rest of the continent put together. Fewer than one in ten South Africans is white, yet 13 of the 15 players in the Springbok rugby team that won the 2007 World Cup were white, the five South African golfers who have won majors are white and most of the country’s best cricketers are white. The nearly all-black national football team, Bafana Bafana, ranks poorly in international standings.

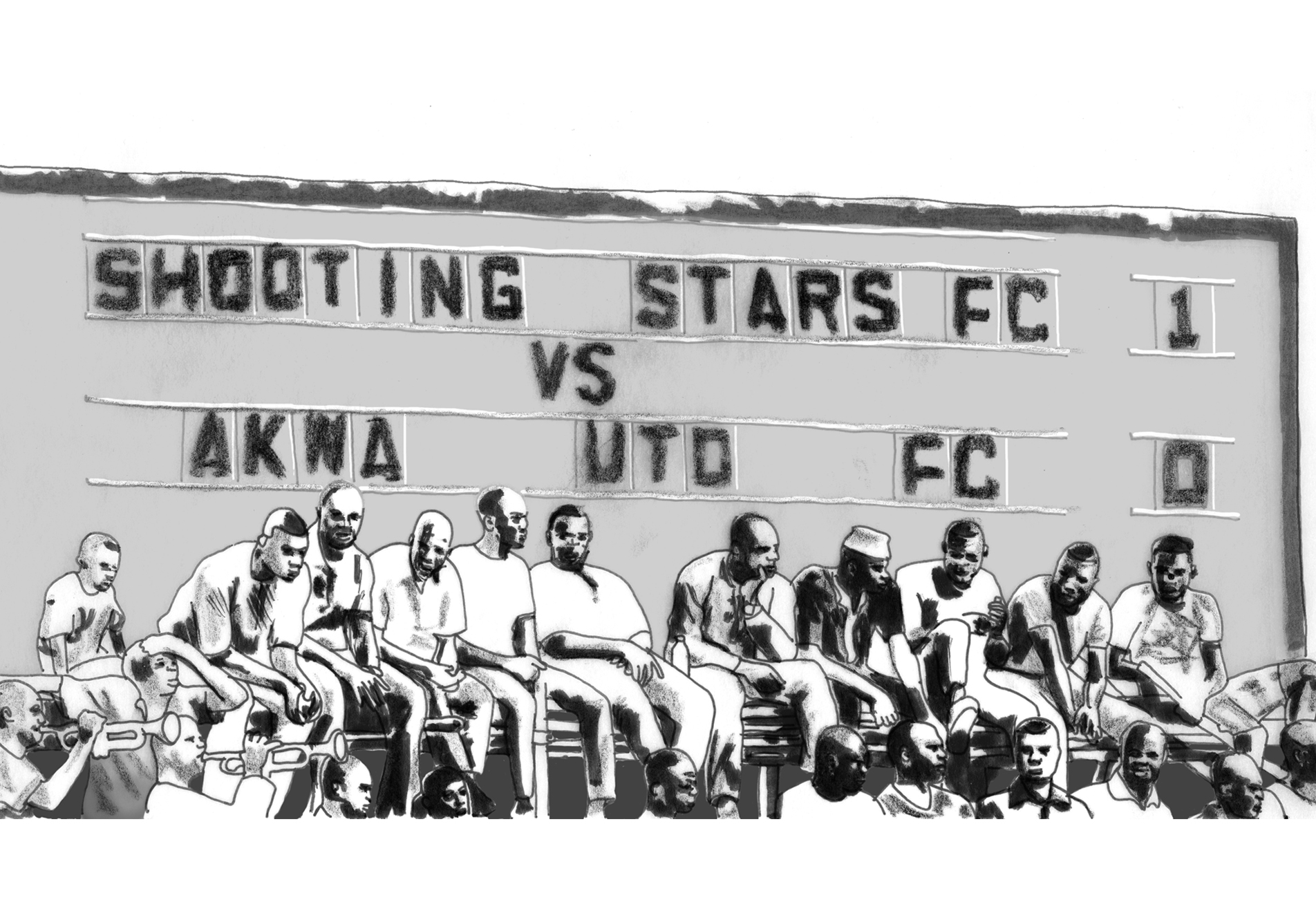

This isn’t to say that white people are genetically better at sport. Rather it’s a question of resources. You are unlikely to grow into a great athlete if you are undernourished, prone to disease, lack good medical care and don’t have access to good coaching. These are still realities for large numbers of Africans. Then there is disorganisation: just before the 2010 Fifa World Cup in South Africa, Nigeria staged a training camp in England, during which the team barely played friendlies because it couldn’t afford to rent stadiums. A game would be arranged, but when the hosting club began to doubt that it would receive any money, the match would be called off. At the 2010 event, the Nigerian Football Association booked the team into a cheap, mosquito-ridden hotel outside Durban and soon had to change it.

But Africa’s biggest problem might be isolation. The best football is played in Western Europe, where 400 million relatively wealthy people live jammed close together, constantly exchanging knowhow across borders. With only about six per cent of the world’s population, Europeans have won six of the last 10 world cup competitions.

Most Africans struggle to access European knowledge networks. They can’t easily travel to Italy or Germany and see how football is played there, let alone talk to the best coaches. And only a few of the very best African players break into the world’s best leagues. One reason why poor countries do badly at sport – and one reason why they are poor – is that they tend to be less networked, less connected to other countries. It is hard for them to access the latest best practice on how to play a sport. So Africa produces neither many stars (like Latin America) nor sophisticated tactics (like Europe).

The importance of being networked is evident when you make a list of top African players in Europe. For a start, there aren’t many of them. Now that Didier Drogba, Samuel Eto’o and Michael Essien are winding down their careers, only a handful of Africans are stars in their prime with big European clubs: Yaya Touré at Manchester City, Andre Ayew at Olympique Marseille, Kevin-Prince Boateng at Milan, John Obi Mikel at Chelsea and Alex Song, who these days sits on Barcelona’s bench. The sad truth is that Belgium probably has more players with major European clubs than does all of Africa put together. This fact belies the popular African notion that Europeans are constantly exploiting the continent’s football for ‘raw materials’.

The second thing to note is how many of today’s African stars were actually raised in Europe. Drogba flew from Ivory Coast to France alone, aged five, clutching his favourite stuffed animal on a teary flight, to live with an uncle who was a professional footballer in the French league. He has spent very little time in Ivory Coast since. Boateng was born and raised in Berlin; in fact, his half-brother, Jerome, plays for Germany. Ayew, the son of the great Ghanaian player, Abedi Pele, was born in France and moved back there as a teenager. They are among the few Africans who had early access to European knowledge networks. For the same reason, most of the Senegalese team that reached the 2002 World Cup quarterfinal were de facto Frenchmen, of Senegalese parents, but born and raised in France.

If you stay in Africa beyond the age of sixteen, you almost certainly won’t make the top. That’s why most great players of African origin were born, or at least raised, in Europe: Zinedine Zidane (born in France to Algerian parents); Patrick Vieira (moved from Senegal to France as a child); Marcel Desailly (born in Ghana, raised in France); and now the excellent Belgian generation of Kompany-Fellaini-Lukaku plus Moussa Dembele (the Spurs player with a Malian father). From Drogba to Paul Pogba (a young Frenchman of Guinean parents now starring in the Juventus midfield), African footballers have little future in Africa.

Happily, this may change, chiefly because of economics. Six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies of the last decade were in Africa, according to The Economist. One nice side-effect might be in football. It’s no coincidence that Ghana, Africa’s best performer in the last two World Cup competitions, is a democracy where incomes have been growing by more than five per cent a year.

Better-organised, richer countries tend to do better at sport. There’s hope for African football yet.

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

In this issue, artists and writer from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states. To read the article in full get a copy in our online shop or visit your nearest stockists.

Buy the Chronic

No comments yet.