by Binyavanga Wainaina

(Winner of The Caine Prize 2002)

Cape Town – June, 1995.

There is a problem. Somebody has fallen asleep in the toilet. The upstairs bathroom is locked and Frank has disappeared with the keys. There is a small riot as drunken women with smudged lipstick and crooked wigs bang on the door. There is always that point at a party when people are too drunk to be having fun; when strange smelly people are asleep on your bed; when the good booze runs out and there is only Sedgwick’s Brown Sherry and a carton of sweet white wine; when you realise that all your flatmates have gone and all this is your responsibility; when the DJ is slumped over the stereo and some strange person is playing Brenda Fassie’s latest hit over and over again.

I have been studying here, in Umtata, South Africa, for five years and have rarely breached the boundary of my clique. Fear, I suppose, and a feeling that I am not quite ready to leave a place that has let me be anything I want to be and provided not a single predator. That is what this party is all about:

I am going home for a year.

So maybe this feeling that my movements are being guided is explicable. This time tomorrow I will be sitting next to my mother. We shall soak each other up. Flights to distant places always arouse in me a peculiar awareness: that the substance we refer to as reality is really an organisation as changeable as the puffy white lines that planes leave behind as they fly.

I will wonder why I don’t do this every day. I hope to be in Kenya for 13 months. I intend to travel as much as possible and finally to attend my grandparent’s 60th wedding anniversary in Uganda in December.

There are so many possibilities that could overturn this journey, yet I cannot leave without being certain that I will get to my destination. If there is a miracle in the idea of life it is this: that we are able to exist for a time, in defiance of chaos. Later, you often forget how dicey everything was; how the tickets almost didn’t materialise; how the event almost got postponed; how a hangover nearly made you miss the flight…

Phrases swell, becoming bigger than their context and speak to us as truth. We wield this series of events as our due, the standard for gifts of the future. We live the rest of our lives with the utter knowledge that there is something deliberate that transports everything into place, if we follow the stepping-stones of certainty.

After the soft light and mellow manners of Cape Town, Nairobi is a shot of whisky. We drive from the airport into the city centre.

Around us: Matatus, those brash, garish public transport vehicles, so irritating to every Kenyan except those who own one, or work for one; I can see them as the best example of contemporary Kenyan art. The best of them get new paint jobs every few months: Oprah seems popular right now; the inevitable Tupak. The coloured lights, and fancy horn, the purple interior lighting, the Hip Hop blaring out of speakers I will never afford. Art galleries in Kenya buy only the expression for which there is demand in Europe and America – the real artists, the guys who are turning their lives into vivid colour, are the guys who decorate matatus.

The matatus swing in and out of gaps, darting into impossible angles, turning the traffic into an obstacle course. Watching them with my no-hurry eyes, they seem like a form of jazz: every trip, finding sophisticated and spontaneous solutions to getting their route accomplished as quickly as possible in Nairobi’s ageing, colonial road system, designed for a small driving middle-class. Public transport must just find a way to make do.

Oh and they do.

Manambas conduct the movement of the matatu, hanging out of the open doors, performing all kinds of gymnastics, as they call their routes, announce openings in the traffic, and communicate with the driver through a series of bangs on the roof that manage to be heard above the music. There are bangs for oncoming allies; bangs that warn of traffic jams ahead; bangs announcing an impending traffic policeman. There are also methods to deliver the bribe, without having to stop.

I see one guy, who is hanging on by his fingernails to the roof, one toe in the open door, inches away from death, letting both hands go, and clapping and whistling at a woman who is walking by the side of the road, dressed in tight jeans. She raises her nose and looks determinedly at an electricity pole on the other side of the road. This is Nairobi. This is what you do to get ahead: make yourself boneless, and treat your straitjacket as if it were a game, a challenge. The city is now all on the streets, sweet-talk and hustle. Our worst recession ever has just produced brighter, more creative matatus.

It is good to be home.

In the afternoon, I take a walk down River Road, all the way to Nyamakima. This is the main artery of movement to and from the main bus ranks. It is ruled by manambas, and their image is cynical, every laugh a sneer, the city a war or a game. It is a useful face to carry, here where humanity invades all the space you do not claim with conviction. The desperation that is for me most touching is the expressions of the people who come from the rural areas into the City Centre to sell their produce. Thin-faced, with the large cheekbones common amongst the Kikuyu, cheekbones so dominating they seem like an appendage to be embarrassed about, something that draws attention to their faces when attention is the last thing they want.

Anywhere else those faces are beauty.

Their eyes dart about, consistently uncertain, unable to train themselves to a background of so much chaos. They do not know how to put on a glassy expression.

Those who have been in the fresh produce business longer are immediately visible: mostly old women in khanga sarongs with weary take-it-or-leave-it voices. They hang out in groups, chattering away constantly, as if they want no quiet where the fragility of their community will reveal itself in this alien place.

I take the dawn Nissan matatu to Nakuru.

The Kikuyu-grass by the side of the road is crying silver tears the colour of remembered light; Nairobi is a smoggy haze in the distance. Soon, the innocence that dresses itself in mist will be shoved aside by a confident sun, and the chase for money will reach its crescendo.

A man wearing a Yale University sweatshirt and tattered trousers staggers behind his enormous mkokoteni, moving so slowly it seems he will never get to his destination. He is transporting bags of potatoes. No vehicle gives him room to move. The barrow is so full that it seems that some bags will fall off onto the road. Already, he is sweating. From some reservoir I cannot understand, he smiles and waves at a friend on the side of the road, they chat briefly, laughing as if they had no care in the world. Then the mkokoteni man proceeds to move the impossible.

Why, when all odds are against our thriving, do we move with so much resolution? Kenya’s economy is on the brink of collapse, but we march on like safari ants, waving our pincers as if we will win.

Maybe motion is necessary even when it produces nothing.

I sit next to the driver, who wears a Stetson hat, and has been playing an upcountry matatu classic on the cassette player: Kenny Rogers’ The Gambler. There are two women behind me talking. I can’t hear what they are saying, but it seems very animated.

I catch snatches, when exclamations send their voices higher than they would like.

“Eh! Apana! I don’t believe!”

“Haki!”

“I swear!”

“Me I heard ati…”

Aha. Members of the Me-I-Heard-Ati society.

I construct their conversation in my mind: “Eee-heeee! Even me I’ve heard that one! Ati you know, they are mining oil in Lake Victoria, together with Biwott.”

“Really!”

“Yah!”

“And they are exporting the ka-plant to Australia. They use it to feed sheep.”

“Nooo! Really? What plant?”

“You knooow, that plant — Water-hyak haycy… haia. Argh! That ka-plant that is covering the lake!”

“Hyacinth?”

“Yah! That hya-thing was planted by Moi and Biwott and them in Lake Victoria. They want to finish the Luos!”

The driver changes the tape, and a song comes on that takes me straight back to a childhood memory.

It must have been a Sunday, and I was standing outside KukuDen restaurant in Nakuru, as my mother chatted away with an old friend. It was quite hot, and my Sunday clothes itched. Then this song came on. Congo music, with voices as thick as hot honey, and wayward in a way Christian school tunes hadn’t prepared me for. Guitar and trumpet, parched like before the rains, dived into the honey and out again. The voices pleaded in a strange language, men sending their voices higher than men should, and letting go of control, letting their voices flow, slow and phlegmy, like the honey. There was a lorry outside, and the men unloading the maize were singing to the music, pleading with the honey. The song burst out with the odd Swahili phrase, then forgot itself and started on its gibberish again.

It disturbed me, demanding too much of my attention, derailing my daydreams.

It doesn’t any more.

I am at home. The past eight hours is already receding into the forgotten; I was in Cape Town this morning, I am in Nakuru, Kenya now.

Blink.

Mum looks tired and her eyes are sleepier than usual. She has never seemed frail, but does so now. I decide that it is I who is growing, changing, and my attempts at maturity make her seem more human.

I make my way to the kitchen. The Nandi woman still rules the corridor.

After 10 years, I can still move about with ease in the dark. I stop at that hollow place, the bit of wall on the other side of the fireplace. My mother’s voice, talking to my Dad, echoes in the corridor. None of us has her voice: if crystal were water solidified, her voice would be the last splash of water before it sets.

Light from the kitchen brings the Nandi woman to life. A painting.

I was terrified of her when I was a kid. Her eyes seemed so alive and the red bits growled at me menacingly. Her broad face announced an immobility that really scared me; I was stuck there, fenced into a tribal reserve by her features: rings on her ankles and bells on her nose, she will make music wherever she goes.

Why? Did I sense, so young, that her face could never translate into acceptability?

That, however disguised, it would not align itself to the programme I aspired to?

In Kenya, there are two sorts of people: those on one side of the line will wear thirdhand clothing till it rots. They will eat dirt, but school fees will be paid.

On the other side of the line live people you see in coffee-table books. Impossibly exotic and much fewer in number than the coffee table books suggest. They are like an old and lush jungle that continues to flourish its leaves and unfurl extravagant blooms, refusing to realise that somebody cut off the water.

Often, somebody from the other side of the line.

These two groups of people are fascinated by one another. We, the modern ones, are fascinated by the completeness of the old ones. To us, it seems that everything is mapped out and defined for them, and everybody is fluent in those definitions. The old ones are not much impressed with our society, or manners – what catches their attention is our tools: the cars and medicines and telephones and wind-up dolls and guns. In my teens, set alight by the poems of Senghor and Okot P’Bitek, the Nandi woman became my Tigritude. I pronounced her beautiful, marvelled at her cheekbones and mourned the lost wisdom in her eyes, but I still would have preferred to sleep with Pam Ewing or Iman.

It was a source of terrible fear for me that I could never love her. I covered that betrayal with a complicated imagery that had no connection to my gut: O Nubian Princess, and other bad poetry. She moved to my bedroom for a while, next to the faux- Kente wall hanging, but my mother took her back to her pulpit.

Over the years, I learned to look at her amiably. She filled me with a lukewarm nostalgia for things lost. I never again attempted to look beyond her costume. She is younger than me now; I can see that she has girlishness about her. Her eyes are the artist’s only real success: they suggest mischief, serenity, vulnerability and a weary wisdom. Today, I don’t need to bludgeon my brain with her beauty, it just sinks in, and I find myself desiring her.

I look up at the picture again.

Then I see it.

Have I been such a bigot? Everything: the slight smile, the angle of her head and shoulders, the mild flirtation with the artist. I know you want me, I know something you don’t.

Mona Lisa: nothing says otherwise. The truth is that I never saw the smile. Her thick lips were such a war between my intellect and emotion. I never noticed the smile. The artist is probably not African, not only because of the obvious Mona Lisa business but also because, for the first time, I realise that the woman’s expression is odd. In Kenya, you will only see such an expression in girls who went to private schools, or were brought up in the richer suburbs of the larger towns.

That look, that slight toying smile, could not have happened with an actual Nandi woman. In the portrait, she has covered her vast sexuality with a shawl of ice, letting only the hint of smile reveal that she has a body that can quicken: a flag on the moon. The artist has got the dignity right but the sexuality is European: it would be difficult for an African artist to get that wrong.

The lips too seem wrong. There’s awkwardness about them, as if a shift of aesthetics has taken place on the plain of muscles between her nose and her mouth. Also, the mouth strives too hard for symmetry, as if to apologise for its thickness. That mouth is meant to break open like the flesh of a ripe mango; restraint of expression is not common in Kenya and certainly not among the Nandi, who smile more than any other nation I know.

The eyes are enormous; as if the artist were determined to arouse the sympathy of the viewer, to change a preconceived notion of a woman is. Skins, with “tribal scars” on her face. I can see the gaggle of tourists exclaiming:

“Ooh…such dignity! She’s so… well, noble!”

I turn, and head for the kitchen. I cherish the kitchen at night. It is cavernous, and echoes with night noises that are muffled by the vast spongy silence outside. After so many years in cupboard-sized South African kitchens, I feel more thrilled than I should.

On my way back to my room, I turn and face the Nandi woman, thinking of the fullcircle I have come since I left.

When I left, white people ruled South Africa. When I left, Kenya was a one-party dictatorship. When I left, I was relieved that I had escaped the burdens and guilts of being in Kenya, of facing my roots, and repudiating them. Here I am, looking for them again. I know, her eyes say. I know.

Oh but your land is beautiful!

I’VE GOT a part-time job: driving around Central and Eastern province, and getting farmers to start growing cotton again. I have been provided with a car and a driver. My colleague Kariuki and I are on the way to Mwingi town in a new, zippy Nissan pick-up. The road to Masinga Dam is monotonous, and my mind is has been taken over by bubblegum music, chewing away, trying to digest a vacuum.

That terrible song: “I donever reallywanna IKllTheDragon…”

It zips around my mind like some demented fly, always a bit too fast to catch and smash.

I try to start a conversation, but Kariuki is not talkative. He sits hunched over the steering wheel of the car, body tense, his face twisted into a grimace. He is usually quite relaxed when he isn’t driving, but cars seem to bring out some demon in him. To be honest, Mwingi is not a place I want to visit. It is a new district, semi-arid, and there is nothing there that I have heard is worth seeing or doing, except eating goat. Apparently, according to the unofficial National Goat Meat Quality Charts, Mwingi goat is second after Siakago goat in flavour. I am told some enterprising fellow from Texas started a goat ranch to service the 10,000 Kenyans living there. He is making a killing. South African goat tastes terrible. Over the years in South Africa, I have driven past goats that stare at me with arrogance, chewing nonchalantly, and daring me to wield my knife.

It is payback time.

This is why we set out at six in the morning, in the hope that we would be through with all possible bureaucracies by midday, after which we could get down to drinking beer and eating lots and lots of goat.

I have invested in a few sachets of Andrews Liver Salt. I doze, and the sun is shining by the time I get up. We are 30 kilometres from Mwingi town. There is an intriguing sign on one of the dusty roads that branches off from the highway, a beautifully drawn picture of a skinny red bird and a notice with an arrow: Gruyere.

I am curious, and decide to turn in and investigate. After all, I think to myself, it would be good to see what the Cotton Growing Situation is on the ground before going to the District Agricultural Office.

Ahem.

It takes us about 20 minutes on the dusty road to get to Gruyere. This part of Ukambani is really dry, full of hardy-looking bushes and dust. Unlike most places in Kenya, people live far away from the roads, so one has the illusion that the area is sparsely populated. We are in a tiny village center. Three shops on each side, and a large quadrangle of beaten-down dust in the middle on which three giant wood-carvings of giraffes sit, waiting for transport to the curio markets of Nairobi. There doesn’t seem to be anybody about, we get out of the car, and enter Gruyere, which turns out to be a pub.

It looks about as Swiss as one can get be in Ukambani. A simply built structure with a concrete floor and simple furnishings, it nevertheless has finish – nothing sticking out, everything in symmetry. I notice an ingenious beer-cooler: a little cavern worked into the cement floor, where beer and sodas are cooled in water. This is a relief; getting a cold beer outside Nairobi is quite a challenge.

Kenyans love warm beer, even if it is 40 degrees outside. Since I arrived in these parts, I have had concerned barmaids worrying that I will get pneumonia, or that the beer will go completely flat if left in the fridge for more than twenty minutes.

The owner walks in, burnt salad-tomato red, wearing a kikoi, and nothing else. He welcomes us and I introduce myself and start to chat, but soon discover that he doesn’t speak English, or Kiswahili. He is Swiss, and speaks only French and Kamba. My French is rusty, but it manages to get me a cold beer, served by his wife. She has skin the colour of bitter chocolate. She is beautiful in the way only Kamba women can be, with baby-soft skin, wide-apart eyes, and an arrangement of features that seems permanently on the precipice of mischief.

We chat, and I ask her what brought her husband to Mwingi, and she laughs: “You know mzungus (white people) always have strange ideas! He is a mKamba now, he doesn’t want anything to do with Europe.”

After the heat outside, the brown bottles, shyly poking their heads out of the Cavern of Cool, are tempting. I stick to tea though. I have been frivolous enough today. I can see a bicycle coming a distance, an impossibly large man weaving his way towards us, short rounded legs pumping furiously.

Enter the jolliest man I have ever seen, plump as a mound of ugali, glowing with bonhomie and wiping streams of sweat from his face. There is (of course) the Kamba expression of mischief on his face – only with him, it is multiplied to a degree that makes it ominous. Gruyere’s wife tells me he is the local chief. I stand up and greet him, then ask him to join us. He sits down, and orders a round of beer.

“Ah! You can’t be drinking soda here! This is a bar!”

He beams again, and I swear that somewhere a whole shamba of flowers is blooming.

I try to glide into the subject of cotton, but it is brushed aside.

“So,” he says, “Si you go to South Africa with my daughter? She’s just sitting at home, can’t get a job – Kambas make good wives, you know, you Kikuyus know nothing about having a good time.”

I can’t deny that. He leans close, his eyes round as a full moon, and tells me a story about a retired Major who lives nearby and has three young wives, who complain about his sexual demands. So, it is said that parents in the neighbourhood are worried because their daughters are often seen batting their eyelids whenever he is about.

“You know,” he says, “You Kikuyus cannot think further than your next coin. You grow maize on every available inch of land, and cover your sofas with plastic. Ha! Then, in bed! Bwanaa! Even sex is work! But Kambas are not lazy, we work hard, we fuck well, we play hard. So drink your beer!”

I decide to rescue the reputation of my community. I order a Tusker. Cold.

What a gift charisma is. By eleven, there is a whole table of people, all of us glowing under the chief’s beams of sunlight. My tongue has rediscovered its French, and I chat with Monsieur Gruyere, who isn’t very chatty. He seems to be still under the spell of this place, and as we drink, I can see his eyes running over everyone. He doesn’t seem too interested in the substance of the conversation; he is held more by the mood. It is midday when I finally excuse myself. We have to make our way to Mwingi.

Kariuki is looking quite inebriated, and now the chief finally displays an interest in our mission.

“Cotton! Oh! You will need someone to take you around the District Agricultural Office. He! You are bringing development back to Mwingi!”

We arrive at the District Agricultural Office. Our meeting there is blessedly brief, and we get all the information we want. The chief leads us through a maze of alleys to the best butchery/bar in Mwingi. He, of course, is well known there, and we get the VIP cubicle. Wielding his potbelly like a sexual magnet, he breaks up a table of young women, and encourages them to join us.

Whispered aside:

“You bachelors must surely be starving for female company, seeing that you have gone a whole morning without any.”

We head off to the butcher, who has racks and racks of headless, hanging goats. I am salivating already. We choose four kilos of ribs, and order mutura (blood sausage) as an appetiser.

The mutura is delicious – hot, spicy, and rich – and the ribs tender and full of the herbal pungency that we enjoy in good goat-meat.

After a couple of hours, I am starting to get uncomfortable at the levels of pleasure around me. I want to go back to my cheap motel-room, and read a book full of realism and stingy prose.

No, no, no! says Mr. Chief. You must come to my place, back to the village, we need to talk to people there about cotton. Surely you are not going to drive back after so many beers? Sleep at my house!

Back at the chief’s house, I lay myself under the shade of a tree in the garden, and sleep.

Wake up! Let’s go and party!

I am determined to refuse. But the light embraces me. By the time we have showered and attempted to make our grimy clothes respectable, it is dusk.

As there is only space for two in the front of the pick-up, I have been sitting at the back. I console myself with the view. Now that the glare of the sun is fading, all sorts of things reveal themselves: tiny hidden flowers of extravagant colour. As if, like the chief, they disdain the frugal humourlessness one expects is necessary to thrive in this dustbowl. We cross several dried riverbeds.

We are now so far away from the main-road, I have no idea where we are. This lends the terrain around me a sudden immensity. The sun is the deep yellow of a free-range egg, on the verge of bleeding its yolk over the sky.

The fall of day becomes a battle: Birds are working themselves into a frenzy, flying about feverishly, unbearably shrill. The sky makes its last stand, shedding its ubiquity, and competing with the landscape for the attention of the eye.

I spend some time watching the chief through the back window. He hasn’t stopped talking since we left. Kariuki is actually laughing.

It is dark when we get to the club. I can see a thatched roof, and four or five cars. There is nothing else around. We are, it seems, in the middle of nowhere. We get out of the car.

“It will be full tonight,” says Chief, “Month-end.”

Three hours later, I am somewhere beyond drunk, coasting on a vast plateau of sobriety that seems to have no end. The place is packed.

More hours later, I am standing in a line of people outside the club, a chorus of liquid glitter arcing high out, then down to the ground, then zips close. The pliant nothingness of the huge night above us goads us to movement.

Some well known Dombolo song starts, and a ripple of excitement overtakes the crowd.

This communal goosebump wakes a rhythm in us, and we all get up to dance. One guy, with a cast on one leg, is using his crutch as a dancing aid, bouncing around us like a string-puppet. The cars all around have their inside lights on, as couples do what they do. The windows seem like eyes, glowing with excitement as they watch us on stage. Everybody is doing the Ndombolo, a Congolese dance where your hips (and only your hips) are supposed to move like a ball-bearing made of mercury. To do it right, wiggle your pelvis from side to side while your upper body remains as casual as if you were lunching with Nelson Mandela. In any restaurant in Kenya, a sunny-side up fried egg is called mayai (eggs) tombolo.

I have struggled to get this dance right for years. I just can’t get my hips to roll in circles like they should. Until tonight. The booze is helping, I think. I have decided to imagine that I have an itch deep in my bum, and I have to scratch it without using my hands, or rubbing against anything.

My body finds a rhythmic map quickly, and I build my movements to fluency, before letting my limbs improvise. Everybody is doing this, a solo thing – yet we are bound, like one creature, in one rhythm.

Any Ndombolo song has this section where, having reached a small peak of hipwiggling frenzy, the music stops, and one is supposed to pull one’s hips to the side and pause, in anticipation of an explosion of music faster and more frenzied than before. When this happens, you are supposed to stretch out your arms and do some complicated kung-fu manoeuvres. Or keep the hips rolling, and slowly make your way down to your haunches, then work yourself back up. If you watch a well-endowed woman doing this, you will understand why skinny women are not popular in Africa.

If you ask me now, I’ll tell you this is everything that matters. So this is why we move like this? We affirm a common purpose, any doubts about others’ motives must fade if we are all pieces of one movement. We forget, don’t we, that there is another time, apart from the hour and the minute? A human measurement, ticking away in our bodies, behind our facades.

Our shells crack, and we spill out and mingle.

I join a group of people who are talking politics, sitting around a large fire outside, huddled together to find warmth and life under a sagging hammock of night mass. A couple of them are students at university; there is a doctor who lives in Mwingi town. If every journey has a moment of magic, this is mine. Anything seems possible. In the dark like this, all we say seems free of consequence, the music is rich, and our bodies are lent a brotherhood by the light of the fire.

Politics makes way for Life. For these few hours, it is as if we were old friends, comfortable with each other’s dents and frictions. We talk, bringing the oddities of our backgrounds to this shared plate.

The places and people we talk about are rendered exotic and distant this night. Warufaga… Burnt Forest… Mtito Andei… Makutano…Mile Saba…Mua Hills… Gilgil… Sultan Hamud… Siakago…Kutus… Maili-Kumi…The wizard in Kangundo who owns a shop and likes to buy people’s toenails; the hill, somewhere in Ukambani, where things slide uphill; thirteen-year-old girls who swarm around bars like this one, selling their bodies to send money home, or take care of their babies; the politician who was cursed for stealing money, and whose balls swell up whenever he visits his constituency; a strange insect in Turkana that climbs up your urine as you piss, and causes much pain for a day or two.

Painful things are shed like sweat.

Somebody confesses that he spent time in prison in Mwea. He talks about his relief at getting out before all the springs of his body were worn out. We hear about the guard who got AIDS, and infected many inmates with the disease deliberately before dying. Kariuki reveals himself. We hear how he prefers to work away from home because he can’t stand seeing his children at home without school fees; how, though he had a diploma in Agriculture, he has been taking casual driving jobs for ten years. We hear about how worthless his coffee farm has become. He starts to laugh when he tells us how he lived with a woman for a year in Kibera, afraid to contact his family because he had no money to provide. The woman owned property. She fed him and kept him in liquor while he lived there.

His wife found him by putting an announcement on National Radio.

Some of us break to dance, and return to regroup. We talk and dance and talk and dance, not thinking how strange we will be to each other when the sun is in the sky, and our plumage is unavoidable, and trees suddenly have thorns, and around us a vast horizon of possible problems reseal our defences.

The edges of the sky start to fray, a mauve invasion of the dark that protects us. I can see shadows outside the gate, people headed to the fields.

There is a guy laying on the grass, obviously in agony, his stomach taut as a drum. He is sweating badly. I almost expect the horns of the goat that he had been eating to force themselves through his sweat glands. His friends take him away in a pickup. Self-pity music comes on. Kenny Rogers, A Town like Alice, Dolly Parton. I try to get Kariuki and the chief to leave, but they are stuck in an embrace, howling to the music and swimming in sentiment.

Then a song comes on that makes me insist that we are leaving.

Some time in the 1980s, a Kenyan university professor recorded a song that was an enormous hit. It could best be described as a multiplicity of yodels celebrating The Wedding Vow.

Will you take me (spoken, not sung)

To be your law-(yodel) -ful wedded wife

To love to cherish and to (yodel)

(then a gradually more hysterical yodel): Yieeeeei-yeeeeei….MEN!

…. then just Amens, and more yodels.

Of course, all these proud warriors, pillars of the community, are at this moment yodelling in unison with the music, hugging themselves (beer bottles under armpit), and looking sorrowful.

Soon, the beds in this motel will be creaking, as some of these men forget self-pity and look for a lost youth in the bodies of young girls.

Late afternoon: Sunlight can be very rude. I seem to have developed a set of bumpy new lenses in my eyes. Who put sand in my eyes? Somewhere, in the distance, a war is taking place: Guns, howitzers, bitches, jeeps, and gin and juice.

“Everybody say Heeeey!”

Chief bursts into my room, looking like he spent the night eating fresh vegetables and massaging his body in vitamins. This is not fair.

“Hey bwana, chief”

Is that my voice? I have a wobbly vision of water, droplets cool against a chilled bottle, waterfalls, mountain streams, taps, ice-cubes falling into a glass. Oh to drink.

“Pole about the noise — my sons like this funny music too much.”

There’s somebody in the bed next to me.

Kariuki snores too much.

A fluid disposition: Maasailand

AUGUST 1995. A few minutes ago, I was sleeping comfortably in the front of a Land Rover Discovery. Now, I am woken up suddenly, as the agricultural extension officer makes a mad dash for the night comforts of Narok town. Driving at night in this area is not a bright idea.

It is an interesting aspect of traveling to a new place that for the first few moments, your eyes cannot concentrate on the particular. I am overwhelmed by the glare of dusk, by the shiver of wind on undulating acres of wheat and barley, by the vision of mile upon mile of space free from our wirings. So much is my focus derailed that when I return into myself I find, to my surprise, that my feet are not off the ground, that the landscape had grabbed me with such force it sucked up the awareness of myself for a moment. It occurs to me that there is no clearer proof of the subjectivity (or selectivity) of our senses than at moments like this.

Seeing is almost always only noticing.

There are rotor-blades of cold chopping away in my nostrils. The silence, after the non-stop drone of the car, is as clinging as cobwebs, as intrusive as the loudest of noises. I have an urge to claw it away from my eardrums.

I am in Maasailand.

Not television Maasailand. We are high up in the Mau hills. There are no rolling grasslands, lions, and acacia trees here, there are forests.

Impenetrable woven highland forest, dominated by bamboo. Inside, there are elephants, who come out at night and leave enormous pancakes of shit on the road. When I was a kid, I used to think that elephants, like cats, use dusty roads as toilet paper – sitting on the ground on their haunches and levering themselves forward with their forelegs.

Back on the choosing to see business. I know chances are I will see no elephants for the weeks I am here. I will see people. It occurs to me that if I were white, chances are I would choose to see elephants, and this would be a very different story. That story would be about the wide, empty spaces people from Europe yearn to get lost in, rather than the cosy surround of kin we Africans generally seek.

Whenever I read something by a white writer who stopped by, or lives in Kenya, I am astonished by the amount of game that appears for breakfast at their patios, and the number of snakes that drop into the baths, and cheetah cubs that become family pets. I have seen five or six snakes in my life. I don’t know anybody who has ever been bitten by one.

The cold air is really irritating. I want to breathe in, suck up the moist mountain-ness of the air, the smell of fever tree and dung – but the process is just too painful. What do people do in wintry places? Do they have some sort of nasal sensodyne? I can see our ancient Massey Ferguson wheezing up a distant hill. They are headed this way.

Relief.

A week later, I am on a tractor, freezing, as we make our way from the wheat fields and back to camp. We have been supervising the spraying of wheat and barley in the scattered fields my father leases here.

There isn’t much to look forward to at night here, no pubs hidden in the bamboo jungle. You can’t even walk about freely at night because outside is full of stinging nettles. We will be in bed by seven to beat the cold. I will hear stories about frogs that sneak under your bed and turn into beautiful women who entrap you. I will hear stories about legendary tractor drivers – people who could turn the jagged roof of Mt Kilimanjaro into a neat afro. I will hear about Maasai people, about so-and-so, who got two hundred thousand shillings for barley grown on his land, and how he took off to the Majengo Slums in Nairobi, leaving his wife and children behind, to live with a prostitute for a year.

When the money ran out, he discarded his suit, pots and pans, and furniture. He wrapped a blanket around himself and walked home, whistling happily all the way. Most of all, I will hear stories about Ole Kamaro, our landlord, and his wife Eddah (names changed).

My dad has been growing wheat and barley in this area since I was a child. All this time, we have been leasing a portion of Ole Kamaro’s land to keep our tractors and things and to make camp. I met Eddah when she had just married Ole Kamaro. She was his fifth wife, thirteen years old. He was very proud of her. She was the daughter of a big time chief from near Mau Narok. Most importantly, she could read and write. Ole Kamaro bought her a pocket radio and made her follow him about with a pen and pencil everywhere he went, taking notes.

I remember being horrified by the marriage – she was so young! My sister Ciru was eight and they played together one day. That night, my sister had a terrible nightmare that my dad had sold her to Ole Kamaro in exchange for fifty acres of land. Those few years of schooling were enough to give Eddah a clear idea of the basic tenets of Empowerment. By the time she was eighteen, Ole Kamaro had dumped the rest of his wives.

Eddah leased out his land to Kenya Breweries and opened a bank account where all the money went.

Occasionally, she gave her husband pocket money.

Whenever he was away, she took up with her lover, a wealthy young Kikuyu shopkeeper from the other side of the hill who kept her supplied with essentials like soap, matches and paraffin.

Eddah is the local chairwoman of the KANU Women’s League and so remains invulnerable to censure from the conservative element in the area. She also has a thriving business, curing hides and beading them elaborately for the tourist market at the Mara. Unlike most Maasai women, who disdain growing of crops, she has a thriving market garden with maize, beans, and other vegetables. She does not lift a finger to take care of this garden. Part of the co-operation we expect from her as landlady depends on our staff taking care of her garden.

Something interesting is going on today and the drivers are nervous. There is a tradition among the Maasai, that women are released from all domestic duties a few months after giving birth. They are allowed to take over the land and claim any lovers that they choose. For some reason I don’t quite understand, this all happens at a particular season, and this season begins today. I have been warned to keep away from any bands of women wandering about.

We are on an enormous hill and I can hear the old Massey Ferguson tractor wheezing. We get to the top, turn to make our way down, and there they are: led by Eddah, a troop of about forty women marching towards us dressed in their best traditional clothing.

Eddah looks imperious and beautiful in her beaded leather cloak, red khanga wraps, rings, necklaces and earrings. There is an old woman amongst them, she must be seventy and she is cackling with glee. She takes off her wrap and displays her breasts, which resemble old socks.

Mwangi, who is driving, stops, and tries to turn back, but the road is too narrow: on one side there is the mountain, and on the other, a yawning valley. Kipsang, who is sitting in the trailer with me, shouts, “Aiiii. Mwangi bwana! DO NOT STOP! It seems that the modernised version of this tradition involves men making donations to the KANU Women’s Group. Innocent enough, you’d think — but the amount of these donations must satisfy them or they will strip you naked and do unspeakable things to your body.

So we take off at full speed. The women stand firm in the middle of the road. We can’t swerve. We stop.

Then Kipsang saves our skins by throwing a bunch of coins onto the road. I throw down some notes and Mwangi (renowned across Maasailand for his stinginess) empties his pockets, throws down notes and coins. The women start to gather the money, the tractor roars back into action and we drive right through them.

I am left with the picture of the toothless old lady diving to avoid the tractor. Then standing up, looking back at us and laughing, her breasts flapping like a flag of victory. I am in bed, still in Maasailand. I pick up my father’s World Almanac and Book of Facts 1992. The language section has new words, confirmed from sources as impeccable as the Columbia Encyclopedia and the Oxford English Dictionary. The list reads like an American Infomercial: Jazzercise, Assertiveness Training, Bulimia, Anorexic, Microwavable, Fast-tracker.

The words soak into me. America is the cheerleader. They twirl the baton, and we follow.

There is a word there, skanking, described as: “A style of West Indian dancing to reggae music, in which the body bends forward at the waist and the knees are raised and the hands claw the air in time to the beat; dancing in this style.”

I have some brief flash of us in forty years time, in some generic dance studio. We are practicing for the Senior Dance Championships, plastic smiles on our faces as we skank across the room.

The tutor checks the movement: shoulder up, arms down, move this-way, move-that:

Claw, baby. Claw!

In time to the beat, dancing in this style.

Langat and Kariuki have lost their self-consciousness around me and are chatting away about Eddah Ole Kamaro, our landlady.

“Eh! She had ten thousand shillings and they went and stayed in a Hotel in Narok for a week. Ole Kamaro had to bring in another woman to look after the children!”

“Hai! But she sits on him!”

Their talk meanders slowly, with no direction – just talk, just connecting, and I feel that tight wrap of time loosen, the anxiety of losing time fades and I am a glorious vacuum for a while, just letting what strikes my mind strike my mind, then sleep strikes my mind.

Ole Kamaro is slaughtering a sheep today.

We all settle on the patch of grass between the two compounds. Ole Kamaro makes quick work of the sheep and I am offered the fresh kidney to eat. It tastes surprisingly good: slippery warmth, an organic cleanliness.

Ole Kamaro introduces me to his sister-in-law, Suzannah, tells me proudly that she is in Form-Four. Eddah’s sister. I spotted her this morning staring at me from the tiny window in their manyatta. It was disconcerting at first, a typically Maasai stare, unembarrassed, not afraid to be vulnerable. Then she noticed that I had seen her, and her eyes narrowed and became sassy – street-sassy, like a girl from Eastlands in Nairobi.

So I am now confused how to approach her. Should my approach be one of exaggerated politeness, as is traditional, or with a casual cool, as her second demeanour requested? I would have opted for the latter but her uncle is standing eagerly next to us. She responds by lowering her head and looking away. I am painfully embarrassed. I ask her to show me where they tan their hides. We escape with some relief.

“So where do you go to school?”

“Oh! At St Teresa’s Girls in Nairobi.”

“Eddah is your sister?”

“Yes.”

We are quiet for a while. English was a mistake. Where I am fluent, she is stilted. I switch to Swahili and she pours herself into another person, talkative, aggressive. A person who must have a Tupac t-shirt stashed away somewhere.

“Arhh! It’s so boring here! Nobody to talk to! I hope Eddah comes home early.”

I am still stunned. How bold, and animated she is, speaking Sheng, a very hip street language that mixes Swahili and English and other languages.

“Why didn’t you go with the women today?”

She laughs, “I am not married. Ho! I’m sure they had fun! They are drinking muratina somewhere, I am sure. I can’t wait to get married.”

“Kwani? You don’t want to go to University and all that?”

“Maybe, but if I’m married to the right guy, life is good. Look at Eddah, she is free, she does anything she wants. Old men are good. If you feed them, and give them a son, they leave you alone.”

“Won’t it be difficult to do this if you are not circumcised?”

“Kwani who told you I’m not circumcised? I went last year.”

I am shocked, and it shows. She laughs.

“He! I nearly shat myself! But I didn’t cry!”

“Why? Si, you could have refused.”

“Ai! If I had refused, it would mean that my life here was finished. There is no place here for someone like that.”

“But…”

I cut myself short. I am sensing this is her compromise – to live two lives fluently. As it is with people’s reasons for their faiths and choices – trying to disprove her is silly. As a Maasai, she will see my statement as ridiculous.

In Sheng, there is no way for me to bring it up that would be diplomatic, in Sheng she can only present this with a hard-edged bravado, it is humiliating. I do not know of any way we can discuss this successfully in English. If there is a courtesy every Kenyan practices, it is that none of us ever questions each other’s contradictions; we all have them, and destroying someone’s face is sacrilege.

There is nothing wrong with being what you are not in Kenya, just be it successfully. Almost every Kenyan joke is about somebody who thought they had mastered a new persona and ended up ridiculous.

Suzanna knows her faces well.

Christmas in Bufumbira

DECEMBER 20th 1995: The drive through the Mau Hills, past the Rift Valley and onwards to Kisumu bores me. I haven’t been this way for ten years, but my aim is to be in Uganda. We arrive in Kampala at ten in the evening. We have been on the road for over eight hours.

This is my first visit to Uganda, a land of incredible mystery for me. I grew up with her myths and legends and her horrors, narrated with the intensity that only exiles can muster. It is my first visit to my mother’s ancestral home; the occasion is her parents’ 60th wedding anniversary.

It will be the first time that she and her ten surviving brothers and sisters have been together since the early 1960s. The first time that my grandparents will have all their children and most of their grandchildren at home together; more than a hundred people are expected.

My mother, and the many relatives and friends who came to visit, have filled my imagination with incredible tales of Uganda. I heard how you had to wriggle on your stomach to see the Kabaka; how the Tutsi king in Rwanda (who was seven feet tall) was once given a bicycle as a present; because he couldn’t touch the ground (being a king and all), he was carried everywhere, on his bicycle, by his bearers.

Apparently, in the old kingdom in Rwanda, Tutsi women were not supposed to exert themselves or mar their beauty in any way. Some women had to be spoonfed by their Hutu servants and wouldn’t leave their huts for fear of sunburn.

I was told about a trip my grandfather took when he was young, with an uncle, where he was mistaken for a Hutu servant and taken away to sleep with the goats. A few days later his uncle asked about him and his hosts were embarrassed to confess that they didn’t know he was “one of us.”

It has been a year of mixed blessings for Africa.

This the year that I sat at Newlands Stadium during the Rugby World Cup in the Cape and watched South Africans reach out to each other before giving New Zealand a hiding. Mandela, wearing the Number Six rugby jersey, managed to melt away, for one incredible night, all the hostility that had gripped the country since he was released from jail. Black people, traditionally supporters of the All Blacks, embraced the Springboks with enthusiasm. For just one night, most South Africans felt a common nationhood. It is the year that I returned to my home, Kenya, to find people so way beyond cynicism that they looked back on their cynical days with fondness.

Uganda is different: this is a country that has not only reached the bottom of the hole countries sometimes fall into, it has scratched through that bottom and free-fallen again and again, and now it has rebuilt itself and swept away the hate. This country gives me hope that this continent is not, finally, incontinent.

This is the country I used to associate with banana trees, old and elegant kingdoms, Idi Amin, decay and hopelessness. It was an association I had made as a child, when the walls of our house would ooze and leak whispers of horror whenever a relative or friends of the family came home, fleeing from Amin’s literal and metaphoric crocodiles.

I am rather annoyed that the famous Seven Hills of Kampala are not as clearly defined as I had imagined they would be. I have always had a childish vision of a stately city filled with royal paraphernalia. I had expected to see elegant people dressed in flowing robes, carrying baskets on their heads and walking arrogantly down streets filled with the smell of roasting bananas; and intellectuals from a 1960s dream, shaking the streets with their Afrocentric rhetoric.

Images formed in childhood can be more than a little bit stubborn.

Reality is a better aesthetic. Kampala seems disorganised, full of potholes, bad management, and haphazardness. The African city that so horrifies the West. The truth is that it is a city being overwhelmed by enterprise. I see smiles, the shine of healthy skin, and teeth; no layabouts lounging and plotting at every street corner. People do not walk about with walls around themselves as they do in Nairobbery.

All over, there is a frenzy of building. A blanket of paint is slowly spreading over the city, so it looks rather like one of those Smirnoff adverts where inanimate things get breathed into Technicolor by the sacred burp of forty percent or so of clear alcohol. It is humid, and hot, and the banana trees flirt with you, swaying gently like fans offering a coolness that never materialises.

Everything smells musky, as if a thick, soft steam has risen like broth. The plants are enormous. Mum once told me that, travelling in Uganda in the 1940s and the ’50s, if you were hungry you could simply enter a banana plantation and eat as much as you wished. You didn’t have to ask anybody. But you were not allowed to carry so much as a single deformed banana out of the plantation.

We are booked in at the Catholic Guesthouse. As soon as I have dumped my stuff on the bed, I call up an old school friend, who promises to pick me up. Musoke comes at six and we go to find food. We drive past the famous Mulago Hospital and into town. He picks up a couple of friends and we go to a bar called Yakubu’s.

We order a couple of beers, lots of roast pork brochettes, and sit in the car. The brochettes are delicious. I like them so much, I order more. Nile beer is okay, but nowhere near Kenya’s Tusker.

The sun is drowned suddenly and it is dark.

We get onto the highway to Entebbe. On both sides of the road, people have built flimsy houses. Bars, shops, and cafes line the road the whole way. Many people are out, especially teenagers, guided hormones flouncing about, puffs of fog surrounding their huddled faces. It is still hot outside; paraffin lamps light the fronts of all these premises.

I turn to Musoke and ask, “Can we stop at one of those pubs and have a beer?”

“Ah! Wait till we get to where we are going, it’s much nicer than this dump!”

“I’m sure it is; but you know, I might never get a chance to drink in a real Entebbe pub, not those bourgeois places. Come on, I’ll buy a round.” Magic words.

The place is charming. Ugandans seem to me to have a knack for making things elegant and comfortable, regardless of income. In Kenya, or South Africa, a place like this would be dirty, and buildings would be put together with a sort of haphazard selfloathing; sort of like saying “I won’t be here long, so why bother?” The inside of the place is decorated simply, mostly with reed mats. The walls are well finished, and the floor, simple cement, has no cracks or signs of misuse. Women in traditional Baganda dresses serve us.

I find Baganda women terribly sexy. They carry about with them a look of knowledge, a proud and naked sensuality, daring you to satisfy it.

They don’t seem to have that generic cuteness many city women have, that I have already begun to find irritating. Their features are strong; their skin is a deep, gleaming copper and their eyes are large and oily black.

Baganda women traditionally wear a long loose Victorian-style dress. It fulfils every literal aspect the Victorians desired, but manages despite itself to suggest sex. The dresses are usually in bold colours. To emphasize their size, many women tie a band just below their buttocks (which are often padded).

What makes the difference is the walk.

Many women visualise their hips as an unnecessary evil, an irritating accessory that needs to be whittled down. I guess a while back women looked upon their hips as a cradle for the depositing of desire, for the nurturing of children. Baganda women see their hips as supple things, moving in lubricated circles – so they make excellent Ndombolo dancers. In those loose dresses, their hips filling out the sides as they move, they are a marvel to watch.

Most appealing about them is the sense of stature they carry about them. Baganda women seem to have found a way to be traditional and powerful at the same time – most I know grow more beautiful with age and many compete with men in industry, without seeming to compromise themselves as women.

I sleep on the drive from Kampala to Kisoro.

From Kisoro, we begin the drive to St. Paul’s Mission, Kigezi. My sister Ciru is sitting next to me. She is a year younger than me. Chiqy, my youngest sister, has been to Uganda before and is taking full advantage of her vast experience to play the adult tour guide. At her age, cool is a god.

I have the odd feeling we are puppets in some Christmas story. It is as if a basket weaver were writing this story in a language of weave; tightening the tension on the papyrus strings every few minutes, and superstitiously refusing to reveal the ending – even to herself – until she has tied the very last knot.

We are now in the mountains. The winding road and the dense papyrus in the valleys seem to entwine me, ever tighter, into my fictional weaver’s basket. Every so often, she jerks her weave to tighten it.

I look up to see the last half-hour of road winding along the mountain above us. We are in the Bufumbira range now, driving through Kigaland on our way to Kisoro, the nearest town to my mother’s home.

There is an alien quality to this place. It does not conform to any African topography that I am familiar with. The mountains are incredibly steep and resemble inverted icecream cones. The hoe has tamed every inch of them.

It is incredibly green.

In Kenya, “green” is the ultimate accolade a person can give land: green is scarce, green is wealth, green is fertility.

Bufumbira green is not a tropical green, no warm musk, like in Buganda; nor is it the harsh green of the Kenyan savannah, that two-month-long green that compresses all the elements of life – millions of wildebeest and zebra, great carnivores feasting during the rains, frenzied ploughing and planting, and dry riverbeds overwhelmed by soil and bloodstained water. Nairobi underwater.

It is not the green of grand waste and grand bounty that my country knows. This is a mountain green, cool and enduring. Rivers and lakes occupy the cleavage of the many mountains that surround us.

Mum looks almost foreign now. Her Kinyarwanda accent is more pronounced, and her face is not as reserved as usual. Her beauty, so exotic and head-turning in Kenya, seems at home here. She does not stand out any more, she belongs; the rest of us seem like tourists.

As the drive continues, the sense of where we are starts to seep into me. We are no longer in the history of Buganda, of Idi Amin, of the Kabakas, or civil war, Museveni, and Hope.

We are now on the outskirts of the theatre where the Hutus and the Tutsis have been performing for the world’s media. My mother has always described herself as a Mufumbira, one who speaks Kinyarwanda. She has always said that too much is made of the differences between Tutsi and Hutu; and that they are really more alike than not. She insists that she is Bufumbira, speaks Kinyarwanda. Forget the rest, she says. I am glad she hasn’t, because it saves me from trying to understand. I am not here about genocide or hate. Enough people have been here for that – try typing “Tutsi” on any search engine.

I am here to be with family.

I ask my mother where the border with Rwanda is. She points it out, and points out Zaire as well. They are both nearer than I thought. Maybe this is what makes this coming together so urgent. How amazing life seems when it stands around death. There is no grass as beautiful as the blades that stick out after the first rain. As we move into the forested area, I am enthralled by the smell and by the canopy of mountain vegetation. I join the conversation in the car. I have become self-conscious about displaying my dreaminess and absent-mindedness these days.

I used to spend hours gazing out of car windows, creating grand battles between battalions of clouds. I am aware of a conspiracy to get me back to Earth, to get me to be more practical. My parents are pursuing this cause with little subtlety, aware that my time with them is limited. It is necessary for me to believe that I am putting myself on a gritty road to personal success when I leave home. Cloud travel is well and good when you have mastered the landings. I never have. I must live, not dream about living. We are in Kisoro, the main town of the district, weaving through roads between people’s houses. We are heading towards Uncle Kagame’s house.

The image of a dictatorial movie director manipulating our movements replaces that of the basket-weaver in my mind. I have a dizzy vision of a supernatural producer slowing down the action before the climax by examining tiny details instead of grand scenes.

I see a Continuity Presenter in the fifth dimension saying: “And now our Christmas movie: a touching story about the reunion of a family torn apart by civil war and the genocide in Rwanda. This movie is sponsored by Sobbex, hankies for every occasion” (repeated in Zulu).

My grandmother embraces me. She is very slender and I feel she will break. Her elegance surrounds me and I feel a strong urge to dig into her, burrow into her secrets, see with her eyes. She is a quiet woman, and unbending, even taciturn – and this gives her a powerful charisma. Things not said. Her resemblance to my mother astounds me. My grandfather is crying and laughing, exclaiming when he hears that Chiqy and I are named after him and his wife (Kamanzi and Binyavanga). We drink rgwagwa, banana wine laced with honey. It is delicious, smoky and dry.

Ciru and Chiqy are sitting next to my grandmother. I see why my grandfather was such a legendary schoolteacher: his gentleness and love of life are palpable. At night, we split into our various age groups and start to bond with each other. Of the cousins, Manwelli, the eldest, is our unofficial leader. He works for the World Bank. Aunt Rosaria and her family are the coup of the ceremony. They were feared dead during the war in Rwanda and hid for months in their basement, helped by a friend who provided food. They all survived; they walk around carrying expressions that are more common in children – delight, sheer delight at life.

Rosaria’s three sons spend every minute bouncing about with the high of being alive. They dance at all hours, sometimes even when there is no music. In the evenings, we squash onto the veranda, looking out as far as the Congo, and they entertain us with their stand-up routines in French and Kinyarwanda, the force of their humour carrying us all to laughter.

Manwelli translates one skit for me: they are imitating a vain Tutsi woman who is pregnant and is kneeling to make a confession to the shocked priest: “Oh please God, let my child have long fingers, and a gap between the teeth; let her have a straight nose and be ta-a-all. Oh lord, let her not have a nose like a Hutu. Oh please, I shall be your grateful servant!”

The biggest disappointment so far, is that my Aunt Christine has not yet arrived. She has lived with her family in New York since the early 1970s. We all feel her absence keenly, as it was she who urged us all years ago to gather for this occasion at any cost. She and my Aunt Rosaria are the senior aunts, and they were very close when they were younger. They speak frequently on the phone and did so especially during the many months that Aunt Rosaria and her family were living in fear in their basement. They are, for me, the summary of the pain the family has been through over the years. Although they are very close, they haven’t met since 1961. Visas, wars, closed borders and a thousand triumphs of chaos have kept them apart. We are all looking forward to their reunion.

As is normal on traditional occasions, people stick with their peers; so I have hardly spoken to my mother the past few days. I find her in my grandmother’s room, trying, without much success, to get my grandmother to relax and let her many daughters and granddaughters do the work.

I have been watching Mum from a distance for the past few days. At first, she seemed a bit aloof from it all, but now she’s found fluency with everything and she seems far away from the Kenyan mother we know. I can’t get over the sight of her blushing as my grandmother machine-guns instructions at her. How alike they are. I want to talk with her more, but decide not to be selfish, not to make it seem that I am trying to establish possession of her. We’ll have enough time on the way back.

I’ve been trying to pin down my grandfather, to ask him about our family’s history. He keeps giving me this bewildered look when I corner him, as if he were asking: Can’t you just relax and party?

Last night, he toasted us all and cried again before dancing to some very hip gospel rap music from Kampala. He tried to get grandmother to join him, but she beat a hasty retreat.

Gerald is getting quite concerned that when we are all gone, they will find it too quiet. We hurtle on towards Christmas. Booze flows, we pray, chat and bond under the night rustle of banana leaves. I feel as if I were filled with magic and I succumb to the masses. In two days, we feel a family. In French, Swahili, English, Kikuyu, Kinyarwanda, Kiganda, and Ndebele, we sing one song, a multitude of passports in our luggage. At dawn on December 24, I stand smoking in the banana plantation at the edge of my grandfather’s hill and watch the mists disappear. Uncle Chris saunters up to join me. I ask, “Any news about Aunt Christine?”

“It looks like she might not make it. Manwelli has tried to get in contact with her and failed. Maybe she couldn’t get a flight out of New York. Apparently, the weather is terrible there.” The day is filled with hard work. My uncles have convinced my grandfather that we need to slaughter another bull as meat is running out. The old man adores his cattle but reluctantly agrees. He cries when the bull is killed.

There is to be a church service in the sitting room of my grandfather’s house later in the day.

The service begins and I bolt from the living room, volunteering to peel potatoes outside.

About halfway through the service, I see somebody staggering up the hill, suitcase in hand and muddied up to her ankles. It takes me an instant to guess. I run to her and mumble something. We hug. Aunt Christine is here.

The plot has taken me over now. Resolution is upon me. The poor woman is given no time to freshen up or collect her bearings. In a minute, we have ushered her into the living room. She sits by the door, facing everybody’s back. Only my grandparents are facing her. My grandmother starts to cry.

Nothing is said, the service motors on. Everybody stands up to sing. Somebody whispers to my Aunt Rosaria. She turns and gasps soundlessly. Others turn. We all sit down. Aunt Rosaria and Aunt Christine start to cry. Aunt Rosaria’s mouth opens and closes in disbelief. My mother joins them, and soon everybody is crying. The priest motors on, fluently. Unaware.

End

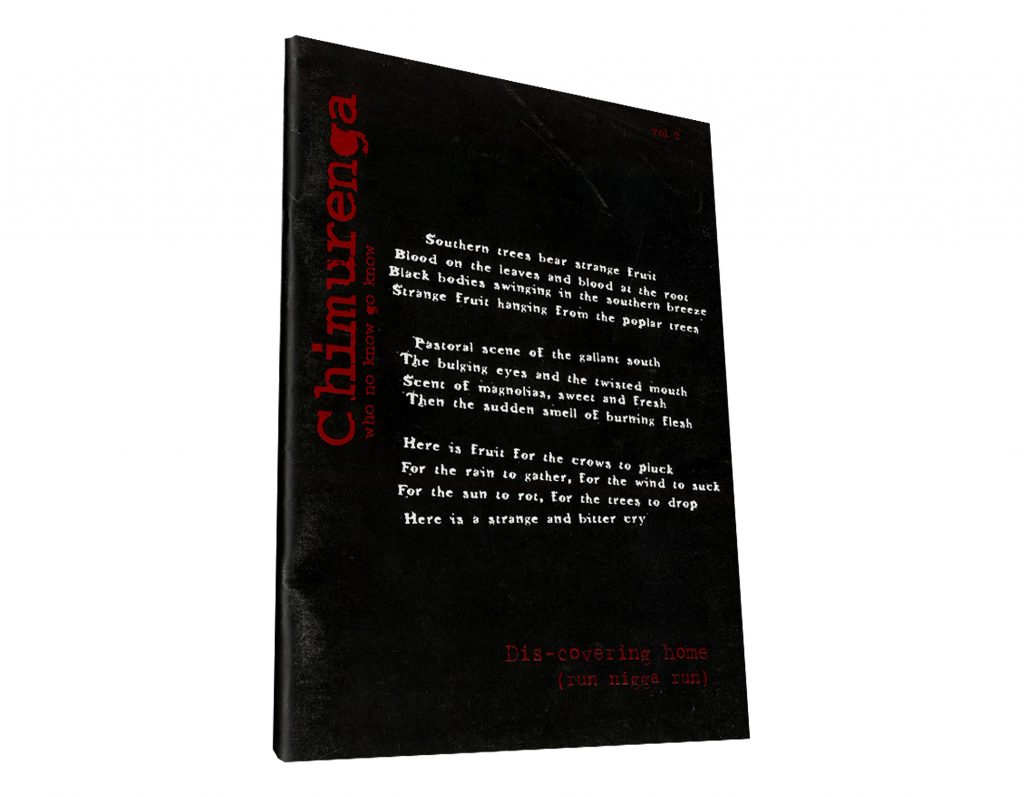

This story, and others, features in Chimurenga 02: Dis-covering Home (July 2002).

Home, lost and found.

Takes by Mahmood Mamdani, Julian Jonker, Henk Rossouw, Binyavanga Wainaina, Gaston Zossou, Haile Gerima, Ashraf Jamal, Noa Jasmine, George Hallet, Jorge Matine, Goddy Leye, Nadia Davids, Zwelethu Mthetwa, Dominique Malaquais, Louis Moholo and many others.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work