By Wendell Hassan Marsh

“Do you believe that Islam is the truth?” a taxi driver in Dakar asked me one afternoon, sounding like a protestant proselytiser casting a net. The corpulent man was leaning close to me in the passenger seat with a glimmer in his eyes, making it clear that he was more interested in offering me an invitation than reaching my destination. Having grown up in the American South, I was all too familiar with the spreading of the Word, its techniques and tactics, but I was struck by a sense of the uncanny. This was no Pentecostal on a mission. Yet, he was earnestly spreading a message.

When I had lived in Dakar several years before, the cosmopolites of the city would jokingly ask me how it was living with the villagers of Ouakam. Once a fishing village nestled in between the volcanic, breast-shaped hills with serene vistas of the western-most point of the African continent, the suburb is now claimed by a sprawling city, forcing the villagers to squeeze into what little land is left, while above them the Lighthouse of Mamelles and the Statue of African Renaissance cast shadows of perpetually unachieved development. Before the boom born of the fantasy of an Africa rising, the most remarkable building in Ouakam came from an entirely different kind of vision. From a certain point, around the time of Maghrib prayers, you can see the twin minarets of the Mosque of the Divine shoot into the heavens like lances or lasers, slicing across a brown-red earth, a cold blue sea and a rose-graded sky. The mosque’s builder, Mohamed Seyni Guèye, saw it in a dream that his followers believe he had during a 14-year spiritual retreat. It was within walking distance of this beach – home of God’s “Khalif on earth” – that I picked up from the driver.

“Well, yes, of course,” I spat out without thinking of meaning or its effects. He studied me briefly, making it clear from the first bismillah that, despite his occupation, driving was not his main preoccupation. He was feeling me out, gauging how receptive I was to his message. He smiled, no doubt reckoning that since I was a believer, he could test the limits of credulity.

“God has written a miracle into my body,” he said, waiting for my response, which this time was not forthcoming. I imagine that he let his words linger so I could catch their weight. He reached into his plain, mass-market boubou and retrieved a picture of his ear. He passed me the phone and asked offhandedly if I could read Arabic. I said that I could. He then turned the phone around, inverting the image of his ear.

“There is the name of God, Allah.”

I had to concede that there was an uncanny resemblance to the four lines and hanging tab that make up the exalted name, but then again, many people see God everywhere. My face must have conveyed that I was on the fence of belief.

“God has shown me the most marvellous things in my sleep. He has made me a miracle. I smoked two packs of cigarettes a day for years. And then one day, I prayed to God and begged him for his help. The next day, I quit.”

I shook my head and said “God is powerful”. He then continued to go through his phone, slowing down to a crawl and running into the pavement once or twice. He gave me the phone again. I saw a photograph of his dark round face in a car.

“What do you see on the lips?”

“Nothing.”

“Here. Zoom in. Can you read Arabic? Look at the letters in white”

“I don’t see anything”

“La illaha ila la. It’s the Shahada.”

His lips just looked chapped and ashy to me. Still, I could see how they gave him enough to animate his imagination. Curved and crossing lines. He showed me more pictures. Here, his body read Subhan Allah. There, it was marked with a crescent. It was interesting, sure. But I was annoyed because we were barely moving and I had somewhere to be. I think he read my annoyance as disbelief.

“What I’m talking about here is beyond reason,” he said with a shrug. “You can’t use it to understand.“

Maybe he read my silence as scepticism. He quickly switched tactics, as if to prove he was not irrational, not backward in the basic sense. He had already told me that he was a retired police officer, that he drove taxis because he had to show his children that you can’t sit at home and expect life to come to you, that you have to keep moving. But now he needed to sharpen the point. He said that he was educated, that he continued to serve as a UN police officer. Okay, I said. I believe it. By now I had arrived at my destination and I was trying to pay.

“So that you don’t think I’m not serious, look.” He passed me his UN ID card. I shook my head and forced a smile and handed it back to him.

As I walked away, I thought of the distance between us and the African Renaissance back in Ouakam. There, the heroic African man holding a boy-child aloft who points to the light of the Statue of Liberty. Here, a regular working man pointing to something that can only be illuminated by faith. If the first represented an elite fantasy, political liberalisation, free-market policies and the emergence of the individual in civil society, the second reflected a scepticism of elite rationality and a rejection of the dichotomous divisions of public and private. Senghor shudders. Or maybe not. This two-track system of elite reason and popular belief has long gotten us where we are.

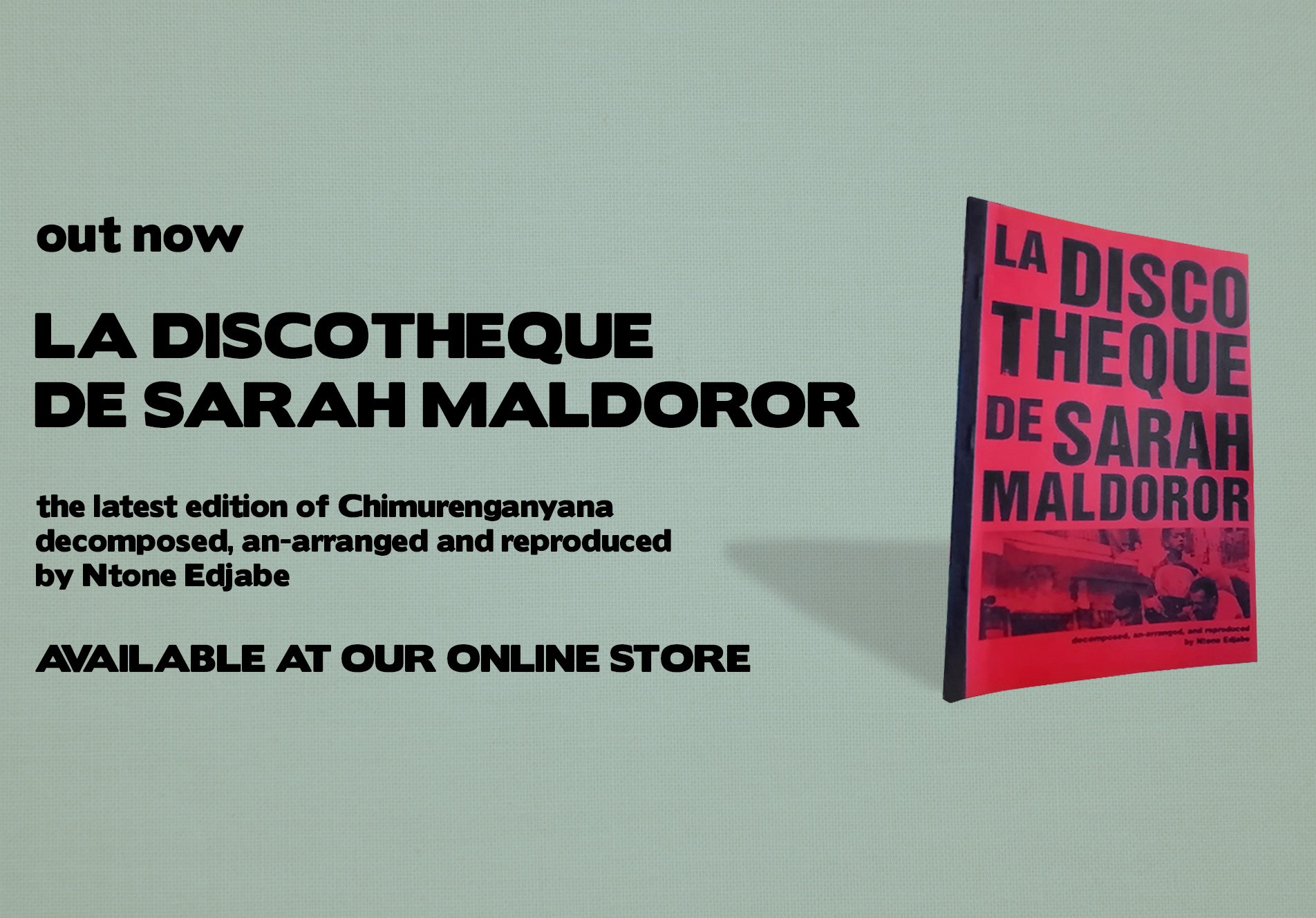

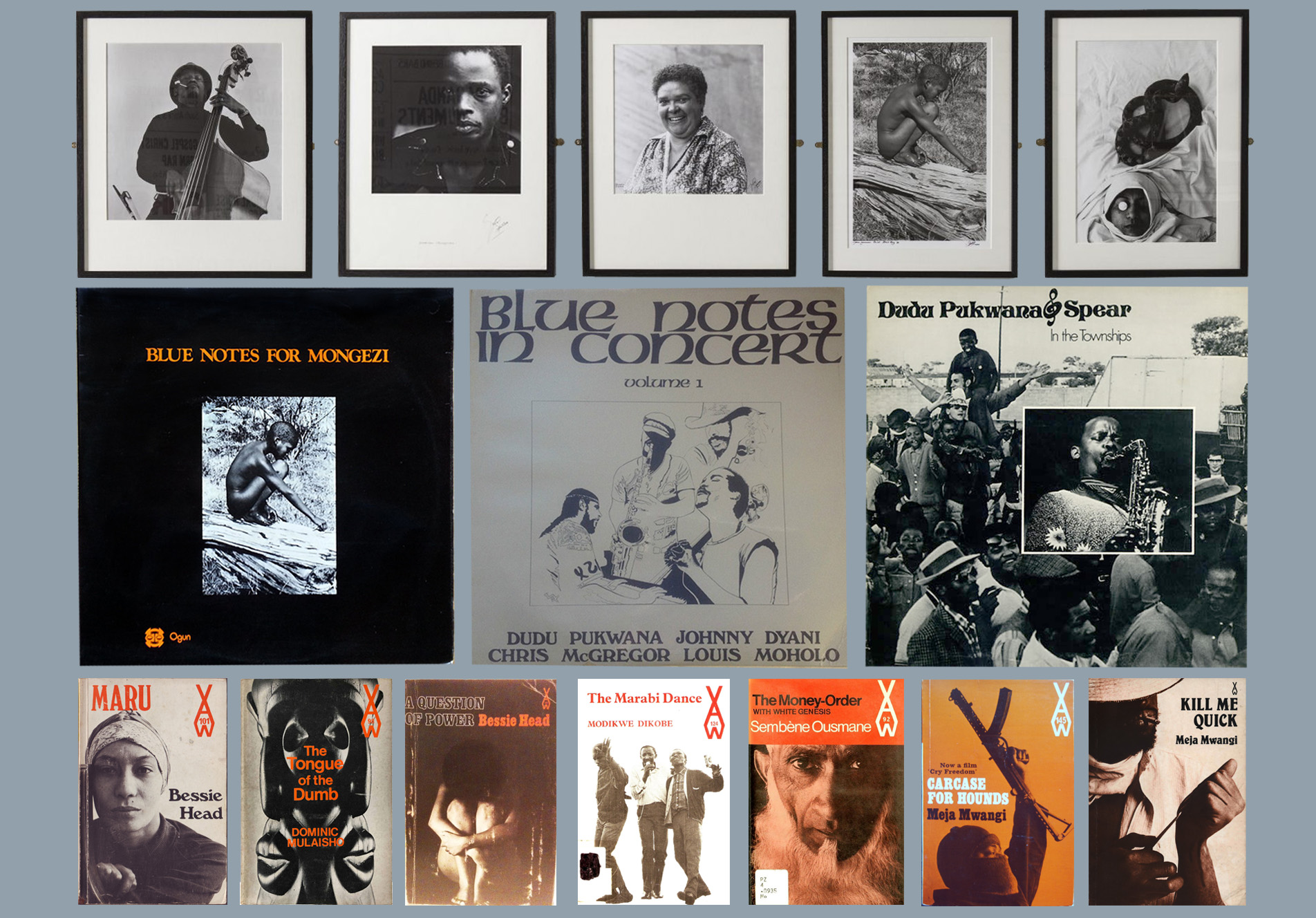

This story features in the Chronic (April 2016), an edition in which we explore the tensions between reform and revolution, and decolonisation and the neoliberal order in the academy, through the lens of history and via the alternate education paradigms based in indigenous knowledge systems, and also arising from South Africa’s radical anti-apartheid struggle.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

Buy the Chronic

No comments yet.