Commonplace readings of Africa narrate the village as a segregated space, its borders demarcated by the subjective, paternal gaze, its memories restricted by linearity and the mirage of urban superiority. Thabo Jijana explores beyond the rural-urban divide and “cremates” the tragedy of relocation, celebrating it instead as a continuous dance of contexts and multiplicities of citizenship.

Any memoir of the rural-urban must quickly descend into a memo of the un-category, the transcendent pause in between heavy breaths, bringing news from the melting pot.

Any memoir of the rural-urban ought to locate the borders of demarcation, “unnecessary” –as Nomboniso Gasa has rightfully said elsewhere – for the sole purpose of pissing on them.

Any memoir of the rural-urban is inclined to interrogate its margins as if a cornered man had collaged his intentions into a kaleidoscope of meanings, trading off contexts and jumping between viewpoints, his only defence being that he equally rejects the supposed superiority of the urban as he does the apparent subjecthood of the rural. Whatever conflicts of interest his words confirm epitomise the break where the rural ends and the urban is yet to begin.

Any memoir of the rural-urban should make use of personal memories, careful not to bind its narrative to the restrictions of the same linearity that got us here in the first place; the continuum of its storylines should dictate the mapping of the argument: “How can we challenge divisions,” as Paddy O’Halloran asks, “both actual and perceived?”

a boy is born in a village:

which is not entirely true – his whole existence may seem to revolve around these 400-odd dwellings of families of former farm hands, but from the clinic he is regularly taken to, to the heavy-duty trucks that occasionally shortcut through the village to rejoin the N2, the rural-urban mirage is brought to dust by the interrelationship, economic or else, of the city and the village;

This article appears in print in the Chronic, April 2017.

the urban imposes itself on him; later he will grow to see his home as outsiders must surely do too, the village as a poorer replica of the urban; whatever is raw and is mined and shipped to the city and later sold back to the village could have been a means of recouping shreds of his originality, but he doesn’t even trust that – the original from the fake, the civilised from the subjected, the lighter from the darker, the how and why of overvaluing these segregated spaces sustaining the conflict;

he could not have come to know the music of Stimela by ear unless the urban asserted itself onto the rural by knocking at the door and driving a “rope of wires” through the mud wall of his grandfather’s hut so there was now “a lamp that need not glow with a matchstick anymore”, dangling from the wooden pillar of the knitted-grass ceiling;

those Jet magazines his mother received every month with a courtesy reminder of where her Sales House account stood, always a watered-down-version-of-MTV offering on the cover, to be skimmed as a feeble attack on boredom;

here is how he remembers radio in his childhood – a snippet of the breakfast show before he left for school; his mother and dabawo, as was the case if he happened to fall sick, would continue into the mid-morning programme, with all its advice on homemade flu remedies, call-in competitions dominated by Omo and insurance companies, and church sermons on Thursdays, usuku loomama; “Umhlobo mhlobo” took it seriously that theirs was to garrison against any eroding influence on the culture of amaXhosa, supplanting not only missionary-backed newspapers of old in its purpose, but arranging their shows so as to reflect elements of rural life: the village men’s meetings reprised as midday call-in dialogues over the latest political controversy, umakhulu/gogo’s storytelling resurfacing as radio drama after supper – now that there is a daycare in his village too, playground songs and iintsomi (courtesy of Nal’ibali) follow the children out of the house;

a boy schools in a village:

the whole concept of economics as a subject seems to disregard the African village’s fiscal health as a crucial marker of a nation that knows how to take care of itself; history asserts the peasant’s authority but capitalism dictates a slanted narrative; “life orientation” – it’s the arts, culture textbooks that bury the village under patronising nostalgic notions of an idyllic pre-colonial society, reducing the rural economy to a commodification of its customs (as when Nelson Mandela employed a personal praise singer when, unlike yesteryears, that was strictly the privilege of kings), making a cottage industry out of its “handcrafts” (as one sees on vendors’ tables in taxi ranks) – anyone who has ever driven past the former Transkei and seen two-storey mansions next to mud flats has no use misplacing their tragedism here;

a boy leaves a village, in/with him:

the city welcomes him too willingly, taking on a subtler face: emaXhoseni is something a city man will say, referring to the village, to disparage a newcomer like him, as if to say “You are among the civilised now; rethink your ways”;

yet, a Mandelafrican taxi rank is not complete without a hawker’s section of traditional medicine;

some Quantum taxis self-advertise for bookings by their owner’s clan name, transplanting the rural’s hereditary code onto the city hub;

the hut in a township is an anomaly, which is not to say a relentless probe will not be rewarded; the prideful ones fasten a bull’s severed horns on a pole in their courtyard;

in 2015, a cousin of his hosted the family at his new house in Struandale Township, just outside the Port Elizabeth CBD; afterwards it was said the ancestors had been apprised of his relocation from his village home in eXesi, near King William’s Town;

in 1927 Kaiser Matanzima built the Bhunga building in the Mthatha cbd and capped the structure with a dome, the whole thing resembling a royal meeting place;

to prepare for her debut Zabalaza, Thandiswa Mazwai “embarked on a pilgrimage” to rural Transkei, above all Mkhankatho, the village of Xhosa songster Madosini. Zabalaza is steeped in Xhosa traditional melodies and cultural wisdoms; Zabalaza conveys the essence of the rural without distorting the urban link;

in Welcome To Our Hillbrow, the shadow of rural Tiragalong seeps into every brushstroke with which Phaswane Mpe paints the enclave of Hillbrow, always aware of the redefinition of home between the “exiled” villager and refugee;

for How Far Have We Come?, Pops Mohamed sought out the Khoisan of the Kalahari desert, recorded their songs, then reworked their originals in a way that merged the rural with the urban, the age-old with the trendy;

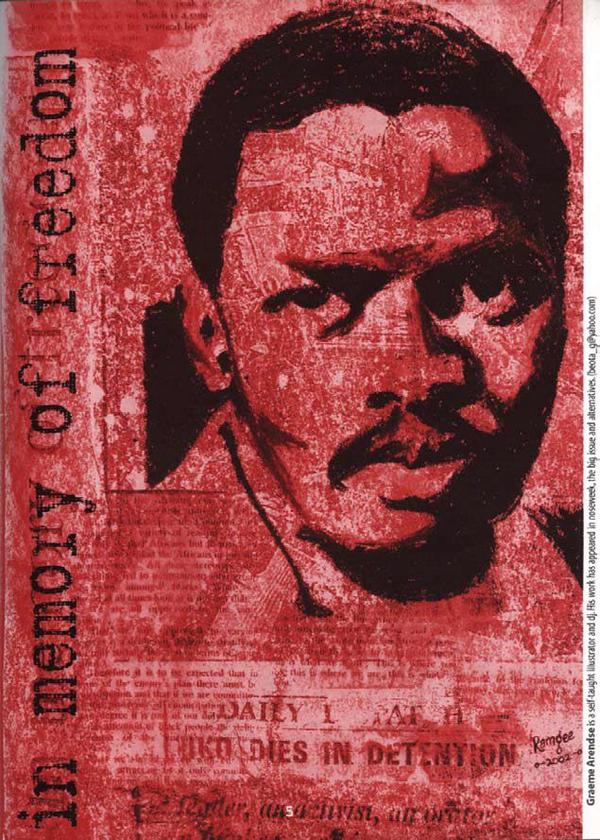

apartheid exiled Gladys Mgudlandu to a home-arrest kind of existence, shunned by the arts press and unable to show anywhere really important; one day she began painting rural scenes on the inside walls of her Gugulethu house, corner to corner, and when she died a new owner refurbished the house. Later, Kemang wa Lehulere had someone chip away layers of paint to uncover a fragment of the paintings, as a “protest against forgetting”.

A memoir of the rural-urban will have to host a night vigil for all pretentions of victimhood relating to exile. Let’s cremate the tragedy of relocation, at least in the villager journeying to the city: people adapt to new contexts without erasing the old – “exile is a tremendous relief,” as Breyten Breytenbach has said, speaking on the “bright side” of exile.

A memoir of the rural-urban must question our interpretation of these interdependent spaces, to say the distance between the city and village speaks to a symbiotic relationship that mimics the complementary nature of animals and their surroundings: one does not live without the other, much as the illusion of independence is a contagion.

A memoir of the rural-urban will have to take in, interpret, and discover any lessons contained in the modern selfie. City-bound selfies tend to be pictures of arrested motion, of doing something fit to brag about, archiving memories, the background synonymous with the star of the show in its visual value: it’s not about who is in the picture per se, but what the selfie-taker was doing and where – the jaunt to the beach, the mall outing, what an office get-together, my last day of the music festival with… An unsaid aversion to revealing too much of the surroundings typically defines most village self-portraits, the field of grass or house wall or gravel road or school premises in the background cropped out to the point of elusiveness or overwhelmed to the margins by the selfie-taker’s image – a recurring image among my WhatsApp contacts is the overhead view, the head-on-a-pillow mugshot: here only the face counts – the aesthetic interest stops with the selfie-taker, reducing the picture to the plainness of an ID photo.

A memoir of the rural-urban will not linger too long over these disparities, of course, though it can and should carry some disclaimer, that is: “Resemblances exist between the rural and urban, but divergences abound… often overwhelming any narrative of parallels.” How to go about explaining this is to focus on the moments where/when the two spaces commingle: a village or city tavern can best be differentiated by the absence of a DStv dish or fancier seats, but you will always find a billiards table inside and on the wall a jukebox stocked with the same popular music currently burning the airwaves. A memoir of the rural-urban won’t use the word “adaptive” in describing the African village, but it can borrow the word’s meaning to dissect what is often referred to as an “African wedding”, these two-tier affairs where the bride and groom swap the Western marriage uniform of a white dress and black and/or white tuxedo for amaprinti, the doek, and the bull’s confirmatory bellow.

a boy answers the city:

In speaking about land as a metaphor for culture, Lewis Nkosi suggests there is a need for stability if one is to be able to construct a sense of self, saying “you can’t have a culture where you are moved from one squatter camp to another”. But what would he make of people like me, who, by a combination of two factors have been made willing migrants – forced by economic circumstances and seeking their true vocation, simply because the metropolis is the unchallenged bedrock of many industries? Citizens locked in a perpetual dance of contexts, to cite Tadeusz Różewicz? Finding a semblance of cohesion in our exiles? I am not talking here of the refugee who finds herself with a series of homes and has little real power to dictate her movements, but am merely evoking an migrant’s spirit for travel, even a polymath’s curiosity with the world – in this updated spectrum, does the village not become a jumping-off point, or one stop among many, different, but no longer presumed worse off than the city or border town, the village now viewed on an equal footing with the city, the village having to fight for recognition based on its cultural knowledge, its potential to accommodate the newcomer’s sense of ambition?

What is it about a villager that seems to set him apart from a city-zen?

Mbulelo Mzamane does not speak much on the history of migration in our context, but the indentured labourer is there in the stories of his that lampoon the villager who migrates to the city, the Mzala. The wandering protagonist of Peter Abrahams’s Mine Boy wanders through the dark night until he finds himself in front of a stranger’s house; he is welcomed thus, “Well, Xuma from the north, I am going to put the light on you. I warn you for your eyes. It is sharp.” The presumption – via author and the character – is that Xuma is unfamiliar with the blinding glow of a torchlight.

Asked about his permanent return to Mandelafrica, Nkosi lays emphasis on the need for there to be space for him to contribute towards the progress of the country, “I can’t come back here and run around the streets.” I’m not the only one who also feels this way – I was not raised on cow-herding, but newspapers and Bona Magazine and the Bible have always been present around the house. The last time I held a hoe was when I still had a 5pm curfew; farming ended with my grandparents – my mother taught for some time at school and my father adopted so well to city life that he picked up karate and an electrician’s skill.

I have three uncles on my mother’s side and in all my 28 years, their home has never been without one of them residing “permanently” in the village… that is, until they left again; no matter how long each is “exiled” – to Plettenburg Bay, the Western Cape winelands, East London’s factories – they always return home to till the garden, as the saying goes.

That I can always return “home” gives me the freedom to absorb external cultures very eagerly, “because they are not warring against [my] identity”, as Albie Sachs says of his own exile, or, to quote him again, “I wasn’t in exile, I lived in exile”, which is where the difference here lies: we do not leave the village on an exit permit, we find comfort in the multiplicity of citizenship.

But then the job ends, opportunities expire, the city loses its spark, or spits the “exiled” villager out.

a boy questions the village:

a) What is a village town like Peddie but a farming settlement that has thoroughly abandoned farming? This is not to say there is no farming – “backyard” farming, subsistence farming, from kitchen garden to mouth, that is still there. But no one lives on the old farms anymore.

b) If no farming, who or what has filled that gap? Peddie counts as neighbours Port Alfred, Grahamstown, King William’s Town. Coastal resorts, game farms, half its youth mostly living in townships like Port Alfred’s, East London, Port Elizabeth, and beyond, and doing all sorts of jobs to earn a living, from low-level jobs and higher up, municipal community projects, and so on.

c) Work is no longer in the village, if it ever was (though the taxi industry and garden-farming with a tractor are two services that have survived the brain drain). “What am I here to stay and do?” childhood friends chide me for asking them to explain their absence when we reunite after a hiatus. Work is a city or town away.

b) What kind of village is this? Contemporary Peddie looks more gentrified by the year, though the pace might be sluggish. Paved streets, government housing. Half of my village owns no cattle. Goats or other livestock? Even less. Well-off families tend to be those whose sons and daughters have made it in the city. The point being, as far as I can tell, amasiko – cultural customs – is the only thing keeping the “exiled” villager’s link with the village stronger. An example: hardly anyone would think to send their boy “into the mountains” anytime during the year; the initiation season is primarily December for a good reason. Another example: Easter, the June holidays, December… these are the best months to host a traditional ceremony since many of a village’s members return from their jobs.

c) Can we say the journeying to the city has become the main rite of passage where I come from? Hasn’t it always been?

d) On the local radio station, the most played ads are for funeral parlours and repair men and furniture shops where paying in instalments is encouraged and delivery is “same day, same time” – some things one would ordinarily associate with a township, not Peddie. If the city is urban and the village rural, what is the township if not an ambassador of the urban?

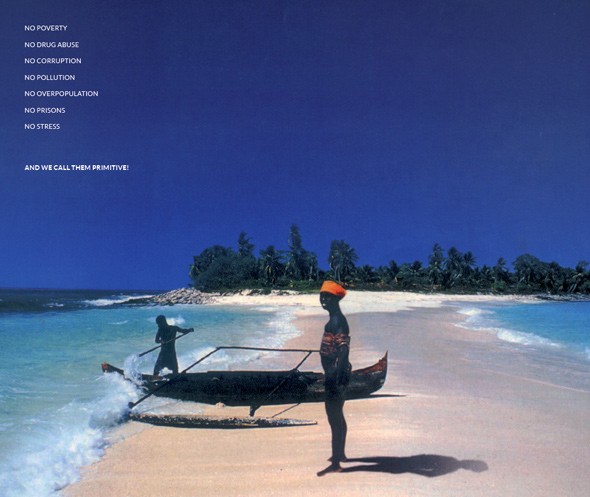

e) The rural is engaged in a protracted process of reimagining itself, in the same way one could say ways of looking at (and thinking about) Africa are changing in line with modern developments and fresh insights into our pasts. Looking at the place the rural occupies in the public imagination, it seems not on par with daily realities.

the village in the city:

Not to perpetuate the marginalisation of the rural by overplaying the city’s advancement.

In an attempt to overturn predominant readings of Africa, we need to identify sites within the continent… not usually dwelt upon in research and public discourse, that defamiliarize commonplace readings of Africa.

Rural as not stagnant, inferior, without potential. As wasteland. Or, one-dimensional.

Discovering the rural in the urban, the urban in the rural highlighted – straddling both these supposedly parallel but dissimilar spaces, refuting the divide.

… but the point is not a subversion or conversion of the urban or rural spaces into their opposites, so obviously we are not talking about the presence of large buildings in the midst of farmland, but rather about a conceptual and political re-perception of what those spheres mean and how they interact.

a boy glimpses the village-city:

It used to be that, because the seat of African indigenous culture was the village, practising “culture” for amaXhosa was specific to the rural – indlu enkulu, the hut/main dwelling where the sacred apparatus of ancestor-worship (umqombothi particularly) could only be housed; the kraal as the only sanctified space to slaughter the sacrificial bull; rites of passage as still seen with the Zulu reed dance, where the participating maidens must travel to a particular river and gather their reeds – but colonialism disrupted that life; apartheid only heightened the dissemination of African cultures to the cities. In instances where boere abandoned their farms and the oldest male member in the families of the workers ended up in the city, the displaced son’s city house was the new site from which to attend to traditional rituals. He did not need to own a kraal; the sacrificial animal was felled in the courtyard; any specific, symbolic tree used in the ritual was fetched from the nearest forest. Suddenly, the village was no longer the only location in which to practise his traditional customs, to anchor his relationship with the ancestors. Suddenly, the city’s ties to the village were manifest in concrete ways. Suddenly, the village, integrated, was the city:

The eclecticism of Great Zimbabwe.

Bury me at the market place, Es’kia Mphahlele says. The site of ritual, of both high and low drama… the silence of death is unmasked for all time.

The chewy bits always come after everyone has wept.

The family has no borders, explains Soboufu Somé of the Dagara people.

Tokoloshes invade my dreams all the time – where do they come from?

Reading List:

Nomboniso Gasa is a researcher and analyst on land, gender, politics, and cultural issues. She is a Senior Research Associate at the Centre for Law and Society, University of Cape Town.

Paddy O’Halloran studied for an MA in Political and International Studies at Rhodes University. “Thinking beyond Divisions with Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject” was published on The Frantz Fanon Blog.

Nal’ibali (isiXhosa for “here’s the story”) is a national reading campaign aimed at children; Nal’ibali story readings are broadcast via several channels, including radio.

Kaiser Matanzima (1915 – 2003) was prime minister of the Transkei Bantustan.

Kemang wa Lehulere is a multi-disciplinary artist based in Cape Town.

Breyten Breytenbach is a writer, poet, and painter. He is quoted here from Out of Exile: NELM Interviews, 1992.

Lewis Nkosi (1936 –2010) was a writer, teacher, and critic; quoted here from Out of Exile: NELM Interviews, 1992.

Tadeusz Różewicz (1921 – 2014) was a Polish poet, playwright, and writer.

Mbulelo Mzamane (1948 – 2014) was a teacher, writer and critic. He counts Mzala: The Short Stories of Mbulelo Mzamane (1980) among his many books.

Albie Sachs is a retired judge, human rights lawyer, teacher, and writer. He is quoted here from Out of Exile: NELM Interviews, 1992.

“In an attempt to overturn…” is quoted from Achille Mbembe & Sarah Nuttall, “Writing the World from an African Metropolis”, Public Culture, 2004.

“… but the point is not…” is taken from “Thinking beyond Divisions with Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject” by Paddy O’Halloran, The Frantz Fanon Blog.

“Bury me at the market place…” is not a direct quote from Es’kia Mphahlele, a writer, teacher and critic, as the line implies. It is a recycling, in the tradition of found poems, of Bury me at the Marketplace, the title of Mphahlele’s selected letters from 1943 –1980, edited by N. Chabani Manganyi (1980). “the site of ritual, of both high and low drama… the silence of death is unmasked for all time” is a direct quote from Manganyi’s introduction to Bury me at the Marketplace.

“The family has no borders, explains Soboufu…” is from Eduardo Galeano’s Mirrors, 2009.

This piece appears in the Chronic (April 2017). An edition which aims to complicate the questions raised by food insecurity, to cook and serve them differently.

Food is largely presented as scarcity, lack, loss – Africa’s always desperate exceptionalism or exceptional desperation or whatever. In this issue, we put food back on the table: to restore the interdependence between the mouth that eats and the mouth that speaks, and to delve deeper into the subtle tactics of resistance and private practices that make food both a subversive art and a site of pleasure.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

No comments yet.