Kiluanji Kia Henda

After several years working as a visual artist with a deep interest in history and a practice rooted in social intervention, I feel compelled to express my admiration and wonder at a series of photographs produced after an online challenge went viral on social networks. “Acaba de me matar” (“Just kill me already”) is more than just a timely protest against the degrading condition of life in the musseques of Luanda – a result of years of wars and the excessive corruption of today. The meme is also a performance event that upstages much of the work produced in the current universe of contemporary art. The performance of this protest takes place on the streets, in puddles of water, in the backyards of houses… places that become ephemeral stages where citizens simulate violent death so as to claim the right to a dignified life. The dramatic charge that animates the images does not allow us to remain indifferent. We are assailed by amazement and revolt. Sadly, sometimes we have to face death to realise that we are still alive.

In the various images that circulate, the inanimate figure of a person lies on the ground somewhere in one of Luanda’s peripheral neighbourhoods. Bodies are smothered by rubble and other urban detritus that conceal the performers’ identities, while also evoking the extreme violence that poverty inflicts on them. The images shock even after we realise that they are staged. More shocking still is the motivation behind the performer’s protest: abject poverty. These protests also highlight the tension between dissatisfaction and lethargy that animates the most vulnerable populations. Without hospitals or schools, without basic sanitation or employment, citizens find themselves incapacitated, unable to react against flagrant injustice. They are crushed and suffocated, powerless to voice discontent; to get it off their chest. The act of protest is internalised. “Acaba de me matar” can also be read as a non-protest. It is simply the image of a dying body, without hope or expectations, pleading for the hand of mercy. A desperate act to escape the slow and painful death that poverty imposes on us.

In the various images that circulate, the inanimate figure of a person lies on the ground somewhere in one of Luanda’s peripheral neighbourhoods. Bodies are smothered by rubble and other urban detritus that conceal the performers’ identities, while also evoking the extreme violence that poverty inflicts on them. The images shock even after we realise that they are staged. More shocking still is the motivation behind the performer’s protest: abject poverty. These protests also highlight the tension between dissatisfaction and lethargy that animates the most vulnerable populations. Without hospitals or schools, without basic sanitation or employment, citizens find themselves incapacitated, unable to react against flagrant injustice. They are crushed and suffocated, powerless to voice discontent; to get it off their chest. The act of protest is internalised. “Acaba de me matar” can also be read as a non-protest. It is simply the image of a dying body, without hope or expectations, pleading for the hand of mercy. A desperate act to escape the slow and painful death that poverty imposes on us.

Despite the violent content of the images, we must not forget that nothing is worse than real life violence. Fiction is, and will always be, a peaceful means of making demands; a territory where we materialise our dreams, but also expell the agonising pain of suffering in silence. We live in constant conflict with reality or at least as it is presented to us. In fiction we seek to eliminate reality and its oppressive stratagems that, as soon as we wake up, force us to obey the social and economic situation in which we live – imprisoned, literally incarcerated.

“Acaba de me matar” is one of the most intelligent protests I’ve ever seen, both for its theatrical staging, and for its effective way of addressing a distressing subject with the proper dose of corrosive irony. I am happy that there is still creativity (which is in fact the most abundant on the outskirts of Luanda) to express the outrage that is felt today. Congratulations to the anonymous authors of this protest! Acaba de me matar, kill me already!

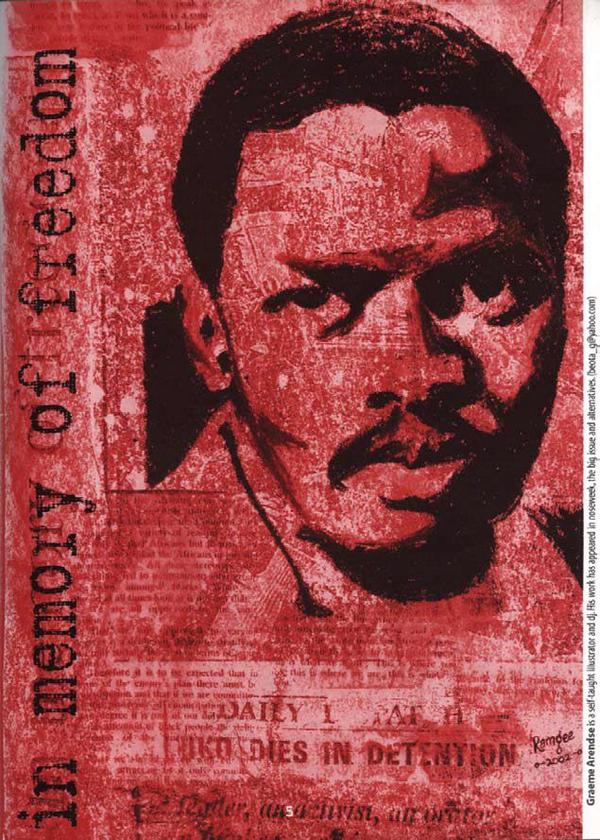

This and other stories available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

No comments yet.