In an age of security, the politics of what and how we eat are fuelled by the tenets of a global food regime that puts agribusiness, with its voracious appetite for social and economic control, at the top of the food chain. Desiree Lewis explores the commodifying systems that rob food of its essence as a source of agency and pleasure.

Politics and scholarship about food in the global South are invariably linked to ideas about deprivation, suffering and political oppression. The emphasis is understandable given the obscenity of our current global food regime: agribusiness destroys local food production; global food suppliers coerce marginalised groups’ reliance on exorbitantly priced processed foods and supermarkets; and the dominant food system effectively creates starvation among many peasants, the urban poor, and the growing economically vulnerable populations in peri-urban areas.

Yet, the political and scholarly attention to food only as an index of injustice and exploitation, and never as a source of agency and pleasure, is disturbing. The visceral and cognitive freedom, pleasure and creativity in relation to cooking, eating and growing food has somehow become suspect to the left – evidence of some incomplete radical commitment, or of capitulating to escapist dreams. Considering that food, cooking and eating are often profoundly creative and pleasurable, the compulsive anxiety, despair and sense of victimisation around food is astonishing. Where does this one-sided attitude towards food come from?

In many ways, it derives from an industry fueled by massive material resources and expert knowledge aimed ostensibly at managing the world’s food crisis. The name of this industry is “food security”, a set of hugely funded practices, expert views and institutions that came into existence alongside development discourses in the mid-1900s, but that have been reactivated by the 21st century obsession with “security”.

In his book-length study, Critique of Security, Mark Neocleous observes that “our whole political language and culture has become saturated by security”, going on to pose the question: “What if security is little more than a semantic and semiotic black hole allowing authority to inscribe itself deeply into human experience?”

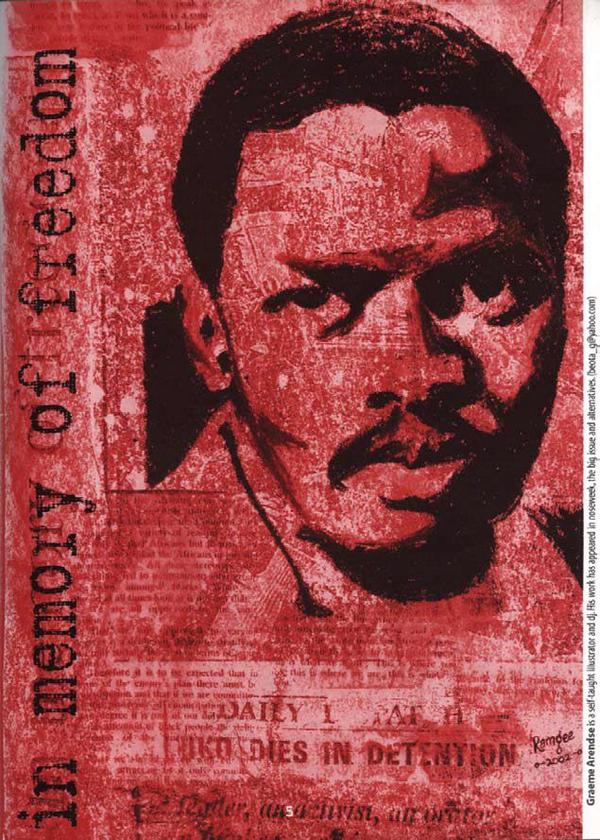

This piece appears in the Chronic, April 2017.

Dominant responses to food certainly suggest that power has been inscribed on bodies in ways that shut down our agencies (even when these are constrained), our hopes and desires, and our feelings of pleasure and joy around growing, cooking and eating food. The drive for “food security” creates space only for attitudes of subjection, victimisation and anxiety.

This drive is widespread, affecting the rich and the poor in both the North and the South. Its impact among poor people in the South is most obvious when it ignores communities’ food sovereignty movements or knowledge-making. The following recommendations from a report undertaken by the Human Sciences Research Council and the National Development Agency about civil societies’ participation in food security initiatives reveals this:

- There is need for more coordinated planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of food security policies and programmes.

- CSOs [Civil Society Organisations] need to actively engage with government as well as providing monitoring services to government plans, programmes and resource allocations to ensure that food security interventions effectively meet their goals.

While seemingly encouraging, the recommendations repeat the myth of a naturalised (and not politicised) food crisis; it renders it apolitical by turning it into some ahistorical dilemma requiring adjustment through efficient state intervention, jacking up government agencies and policy-making, and encouraging collaboration between civil society and the state.

Calls for food security, even when not defined as such, are also manifested among the affluent, many of whom are persuaded that buying power and knowledge will protect them from a world food system with tremendous influence to determine what and how we eat. Some of these calls take the form of exhorting those who are “obese” or have diabetes to take control over their bodies through exercising their weak wills. Through reinforcing the dualism of the mind and the body, apprehensions about certain bodies “out of control” come to characterise both those who condemn diabetics and obese people, as well as those seen to fall into these categories.

A connected apprehension linked to a particular kind of “food insecurity” is the obsession with “eating nutritionally” in a context where food is seen only as a requisite for launching the healthy productive body into a world that over-values social productivity and commoditised labour. From this perspective, eating food is somehow pitted against ensuring nutrition, and the growing domains of food science, nutrionalism and public health work in synch with the food industry to determine what we eat.

One manifestation of this is the way certain marketing practices encourage consumers to scrutinise ingredients on packaging, as though the jargon listed there were perfectly intelligible. This is a ritual enactment of being made to feel in control: we have been told by experts what we are eating, so we therefore know, and our anxieties should be mitigated. (It’s worth noting that, despite the listing of ingredients, buyers are told very little that really matters about products. For example, the ingredients listed for hamburgers don’t mention that beef in North America comes from cows that are weaned off grass as calves and then fed on a mush of corn and the re-cycled bodies of other animals. Or that the havoc this wreaks on their systems – and surely on the systems of whoever or whatever eats them – means that a steady diet of antibiotics accompanies their bizarre diet.)

A related marketing strategy involves promoting “functional foods” (including medicinal elements), which promise consumers that they will be uniquely energised, healthy and less prone than others to disease and illnesses. South Africa has seen a dramatic rise in functional foods such as pro-biotic snack bars and protein- and vitamin-enriched cereals. FutureLife, a South African functional food company started in 2008, now sells milkshakes, cereals, breads and snack bars – all of whose prices have rapidly risen over the years. What is often silenced is the fact that the functional food industry is part of the multinational food system that creates all other food commodities. Overall, then, multinational companies are now strategically promoting nutrionalism and functional foods (and increasing sales) in response to consumers’ distress about eating nutritiously.

Responses generated by displays of gourmet expertise in the mass and new media is another indicator of the helplessness created under the current food system. Although these displays focus on the extraordinariness of chefs, the supplication of the viewer is central to the overall spectacle. Since marketing fast and processed food is central to the food industry’s growth, the spectacle of expert chefs in action confirms “ordinary” people’s powerlessness about food work. The message is: the source of a meal lies somewhere else, and not with ourselves.

This piece appears in the Chronic (April 2017). An edition which aims to complicate the questions raised by food insecurity, to cook and serve them differently.

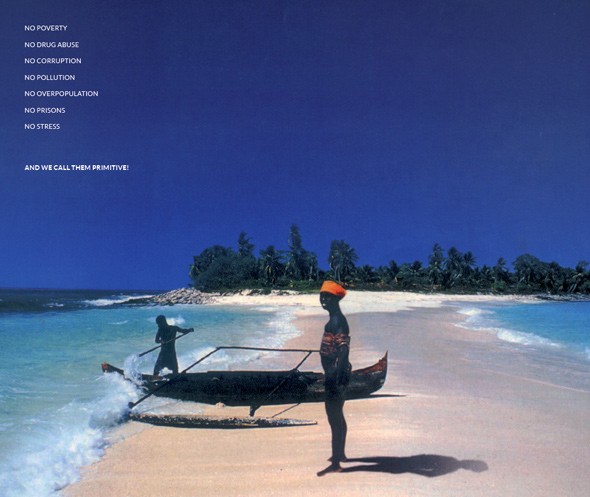

Food is largely presented as scarcity, lack, loss – Africa’s always desperate exceptionalism or exceptional desperation or whatever. In this issue, we put food back on the table: to restore the interdependence between the mouth that eats and the mouth that speaks, and to delve deeper into the subtle tactics of resistance and private practices that make food both a subversive art and a site of pleasure.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

No comments yet.