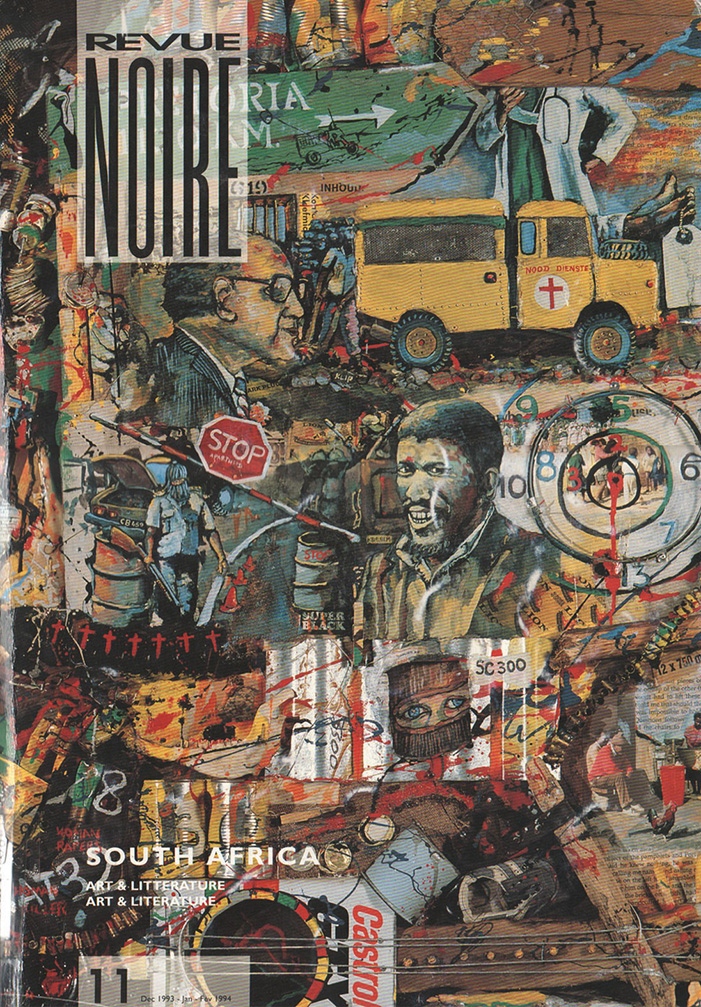

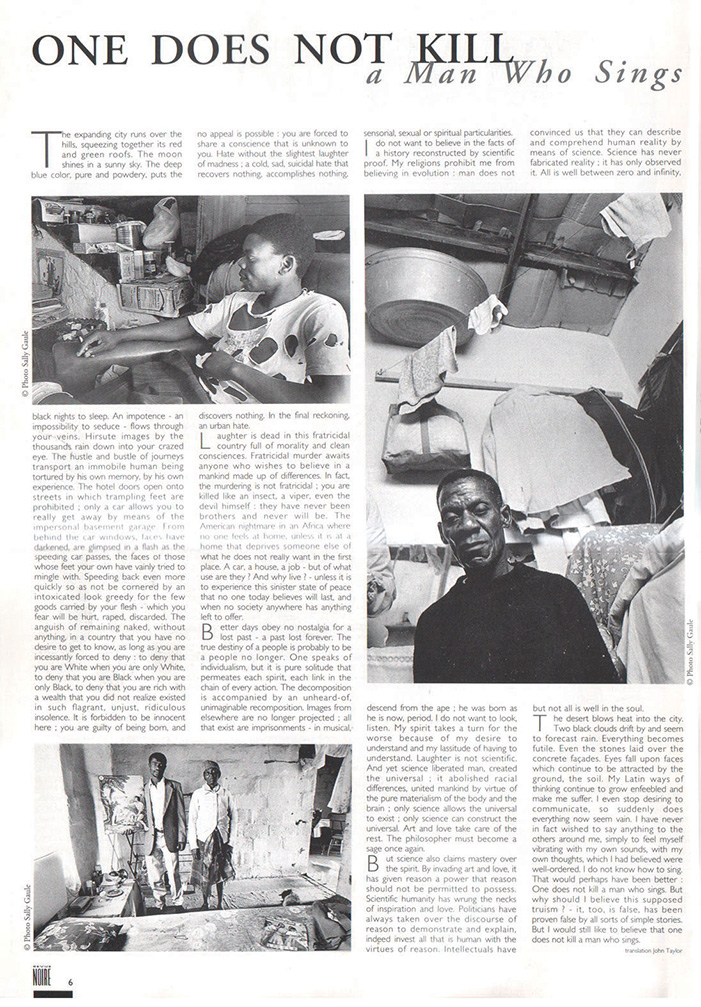

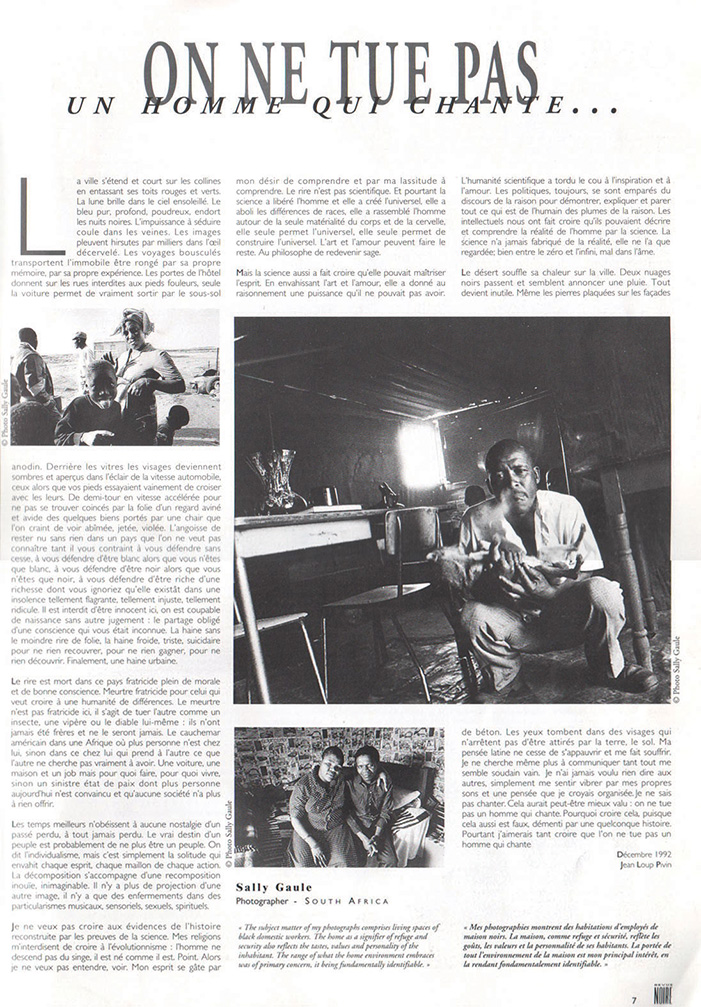

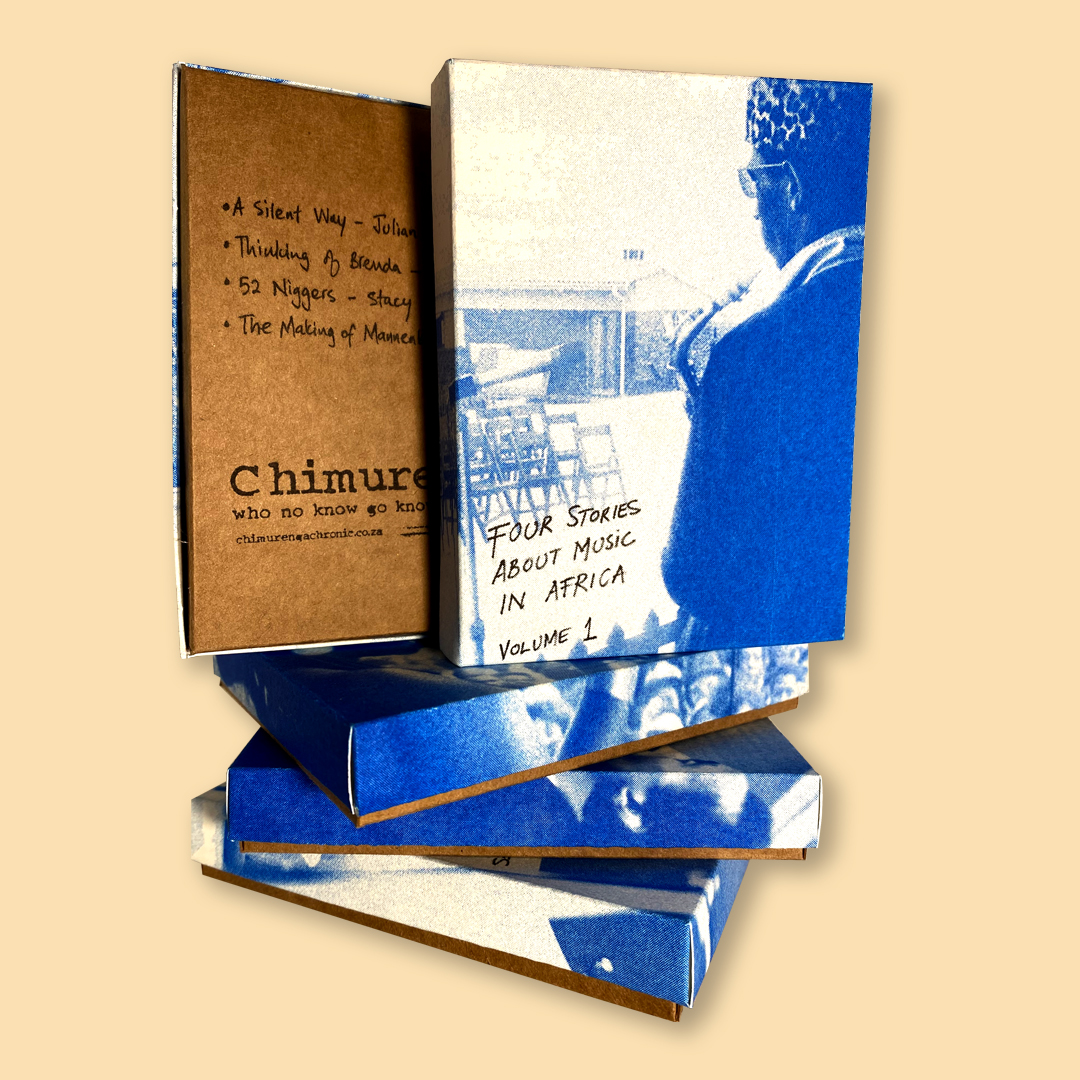

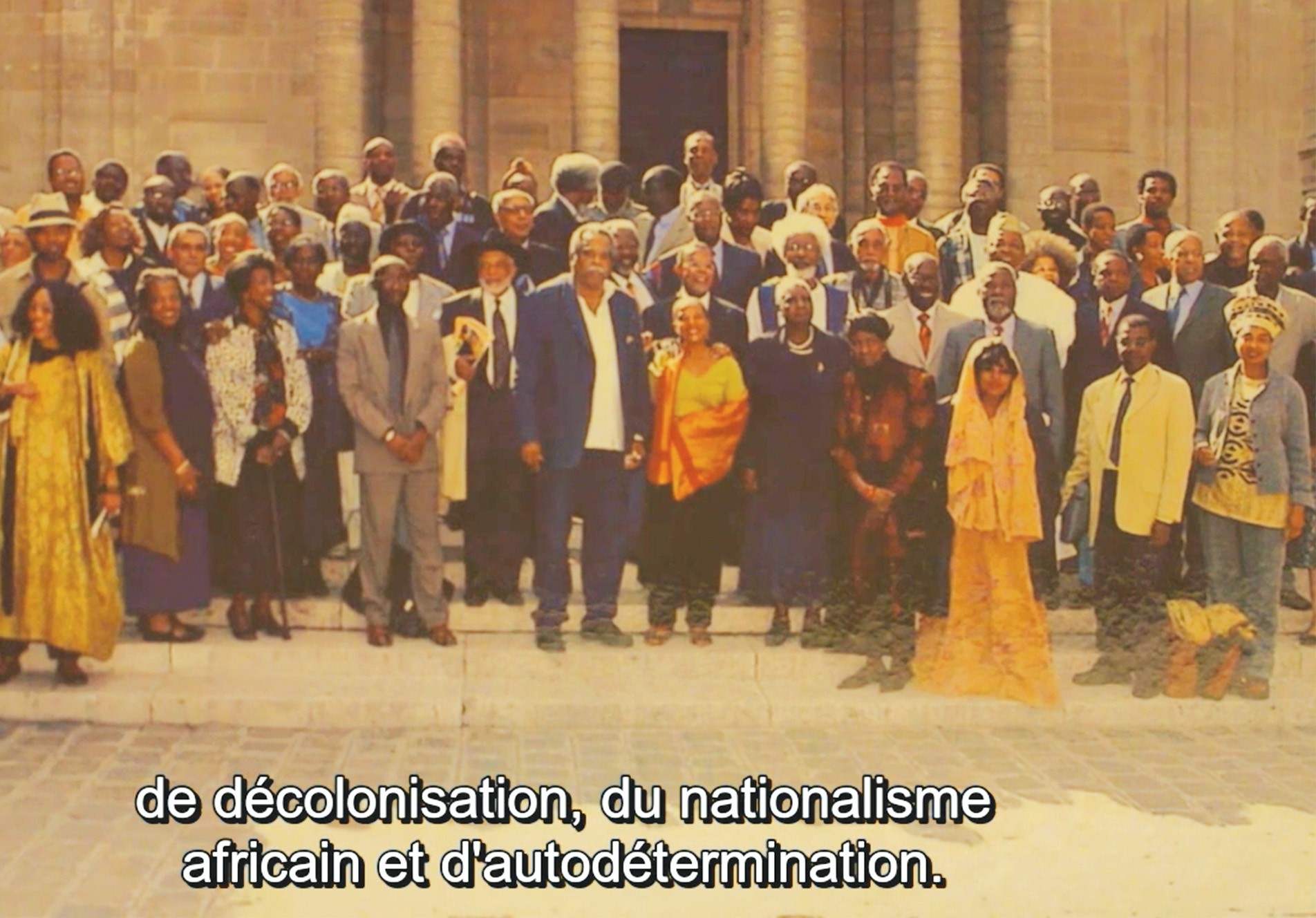

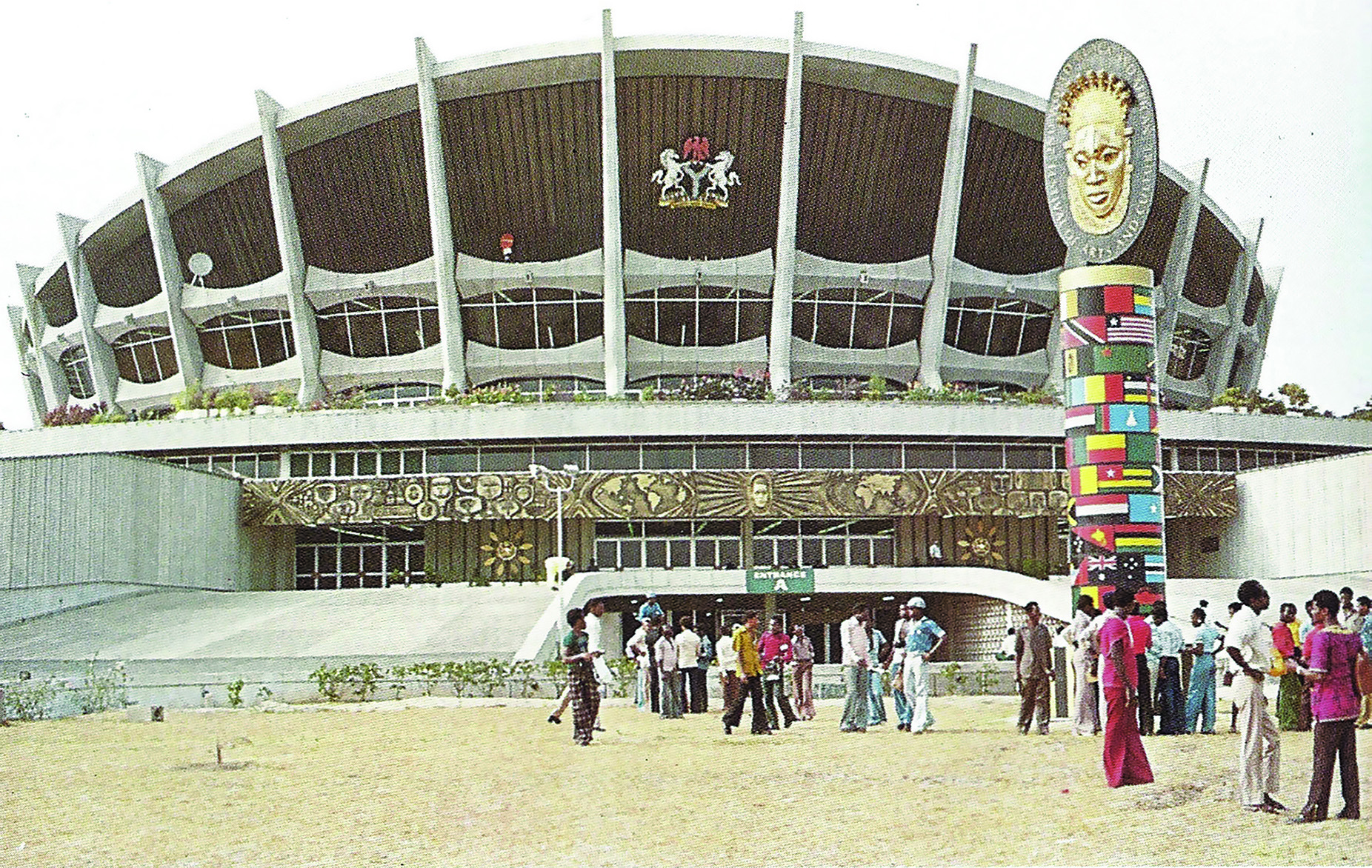

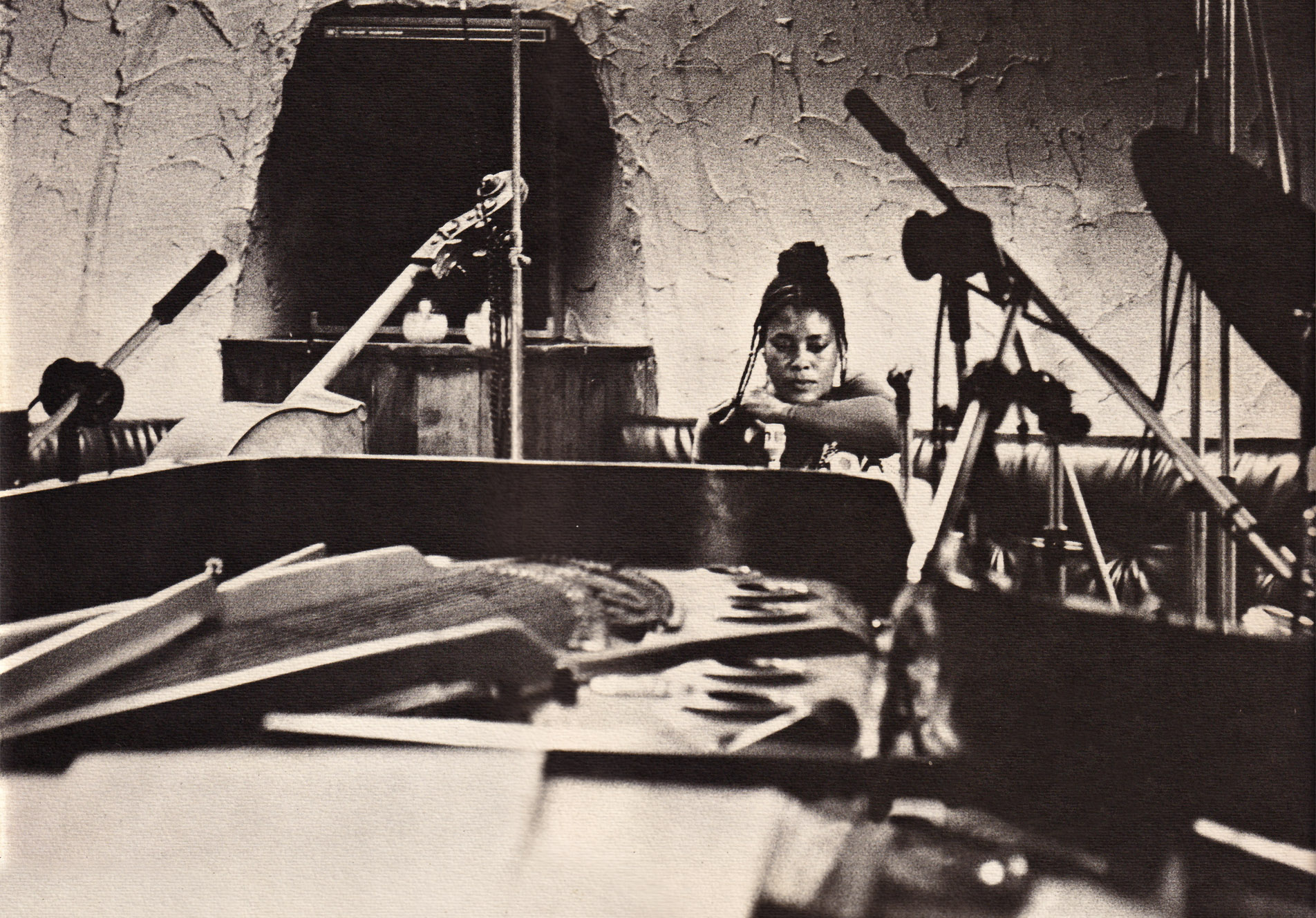

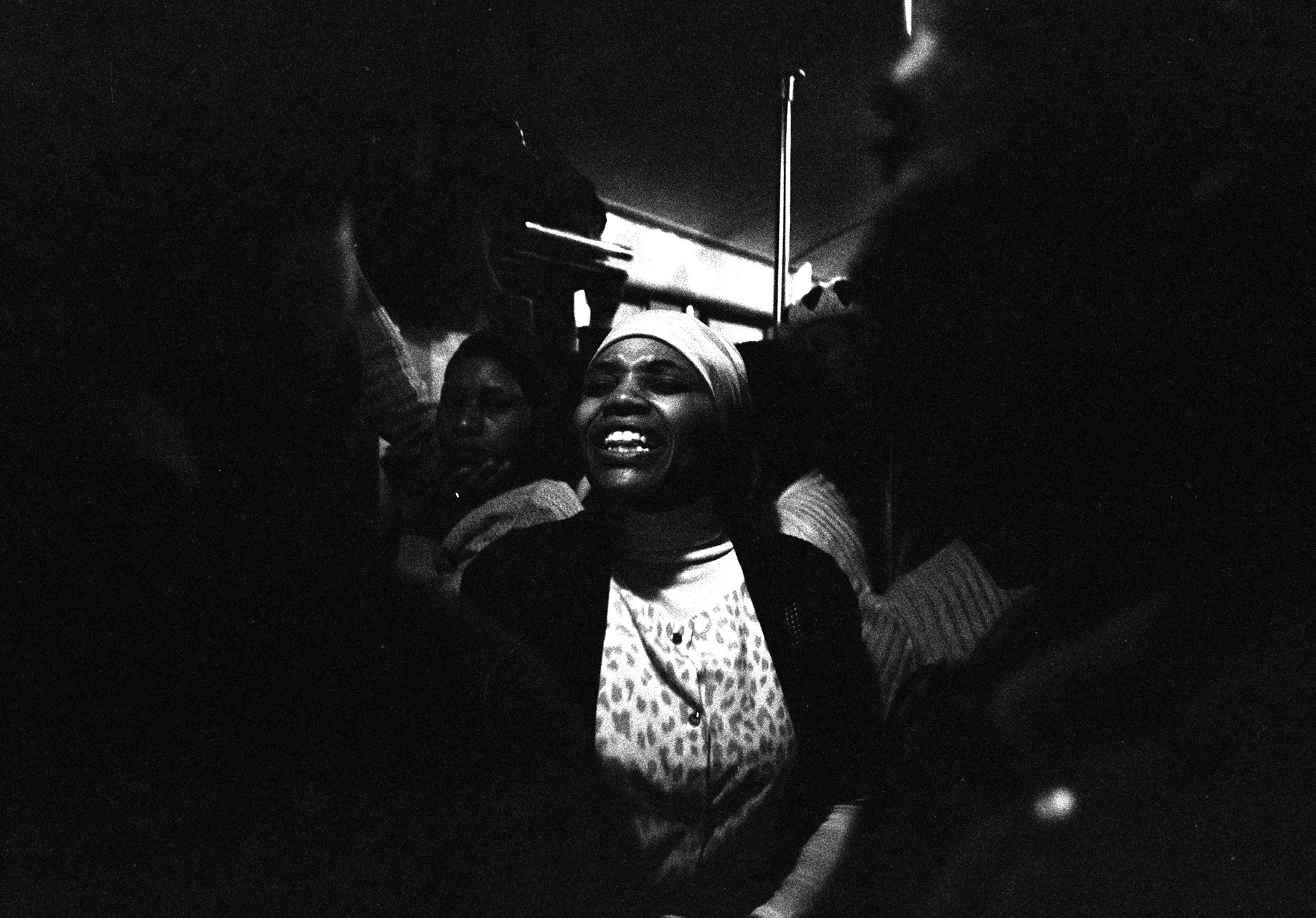

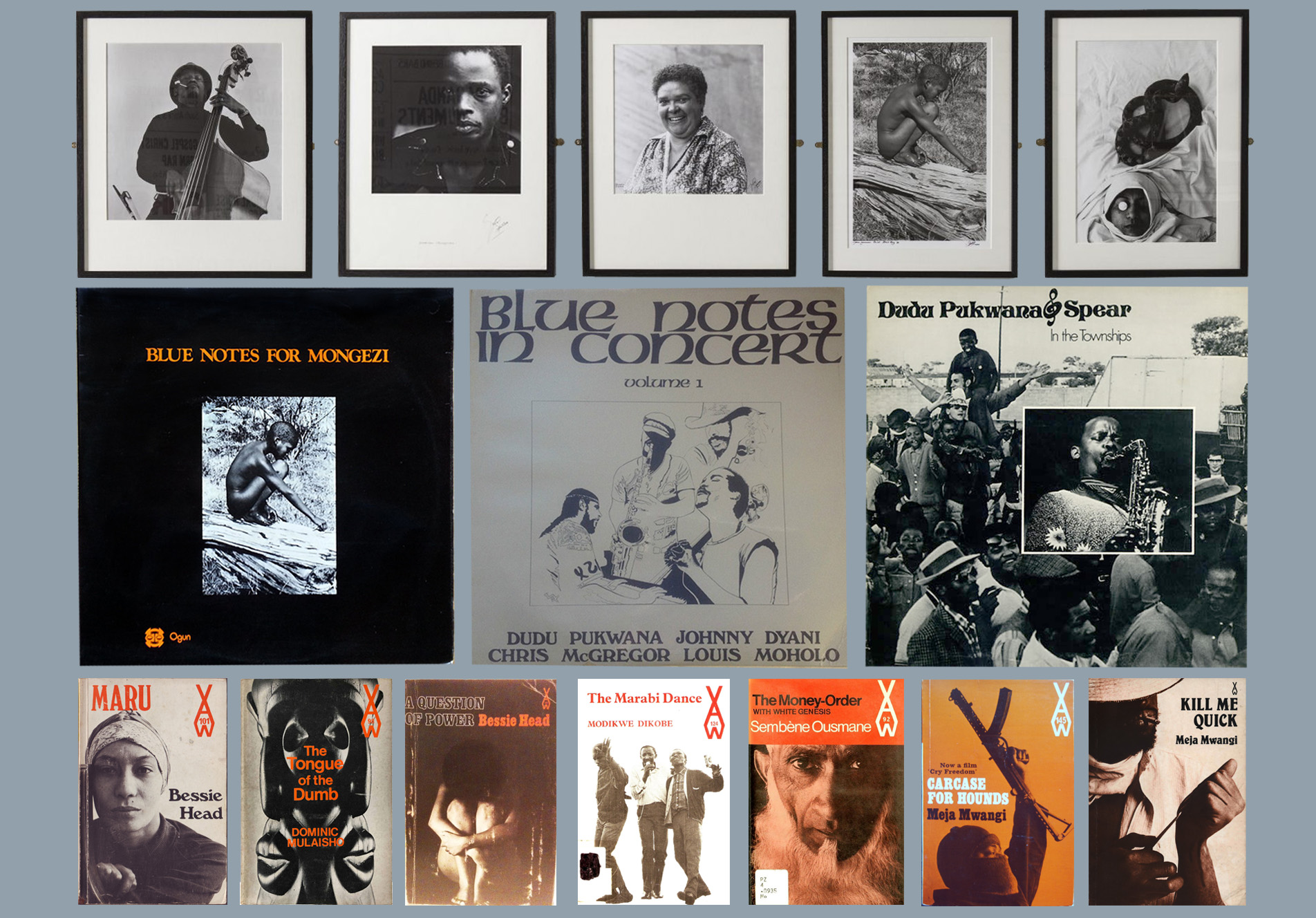

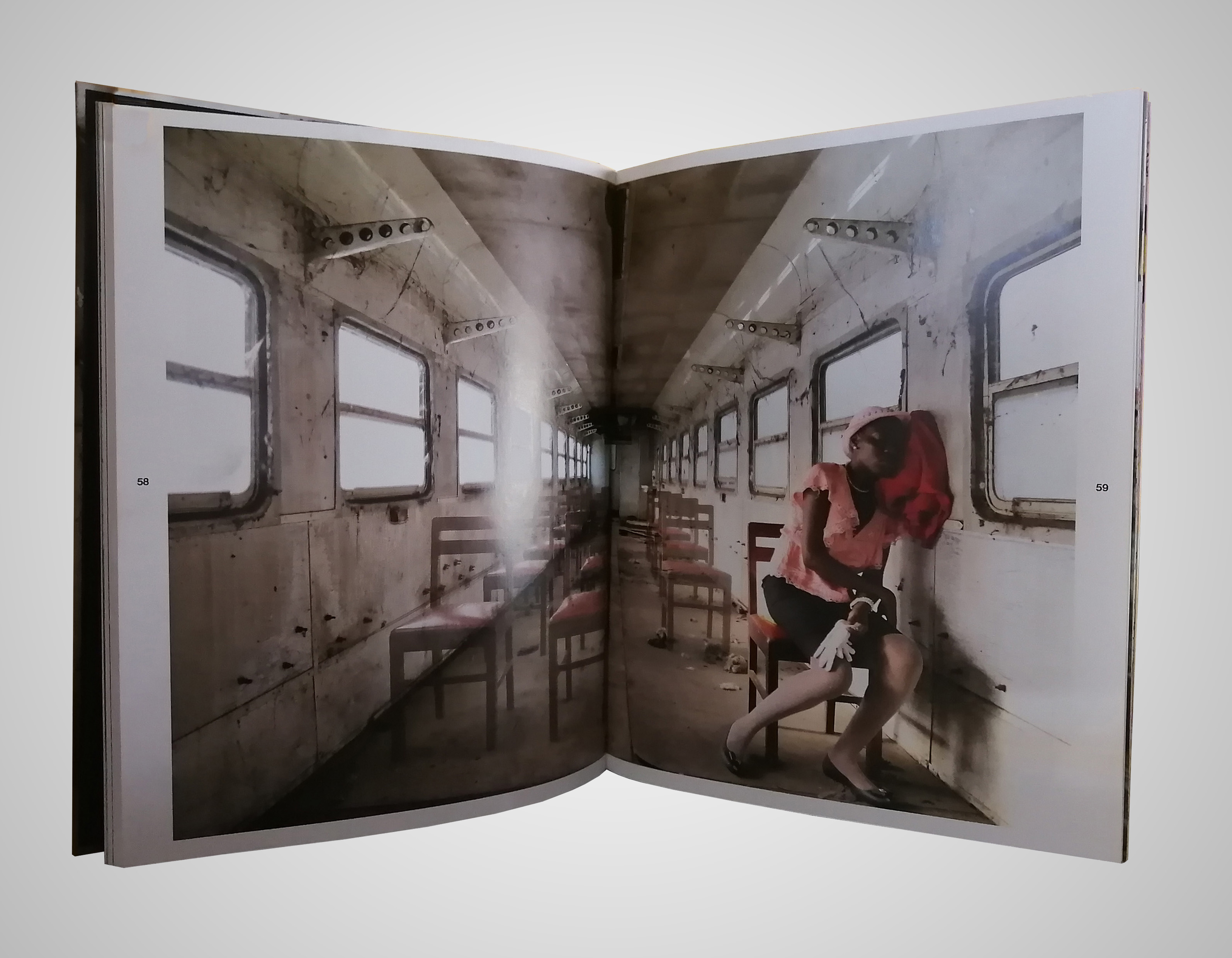

Inspired by the growing, vibrant global community of pan African artists and propelled by the need to challenge reductive exotic and ethnographic approaches to African culture, Jean Loup Pivin and Simon Njami launched Revue Noire in 1991. Conceived as a printed manifestation of the arts at the time, it covered anything from art, architecture and photography, to cinema, literature, theatre, fashion, African cities, AIDS and even gastronomy. Design played a key role in forwarding its objectives. Revue Noire was glossy, fashion savvy and distinctly Parisian.Striking images were combined with largely informative texts that highlighted artistic responses to the international media and the touristic gaze; the production of discourses of cultural identity on the continent; the framing the African body; urban sites; and rapidly changing dynamic between African aesthetic values and Western influences.

As Simon Njami explained, “Dealing with Africa and all the preconceived ideas people have of the continent, we wanted from the very beginning to use the best paper, the best layout, full colour, and at a size that would do justice to the artists that we were introducing. We had to face a double challenge: at the time we started, contemporary African art barely existed. So we were introducing something to an audience that was not aware of what was going on. Therefore, we had to emphasize not only the contents but also the physical look of the magazine.”

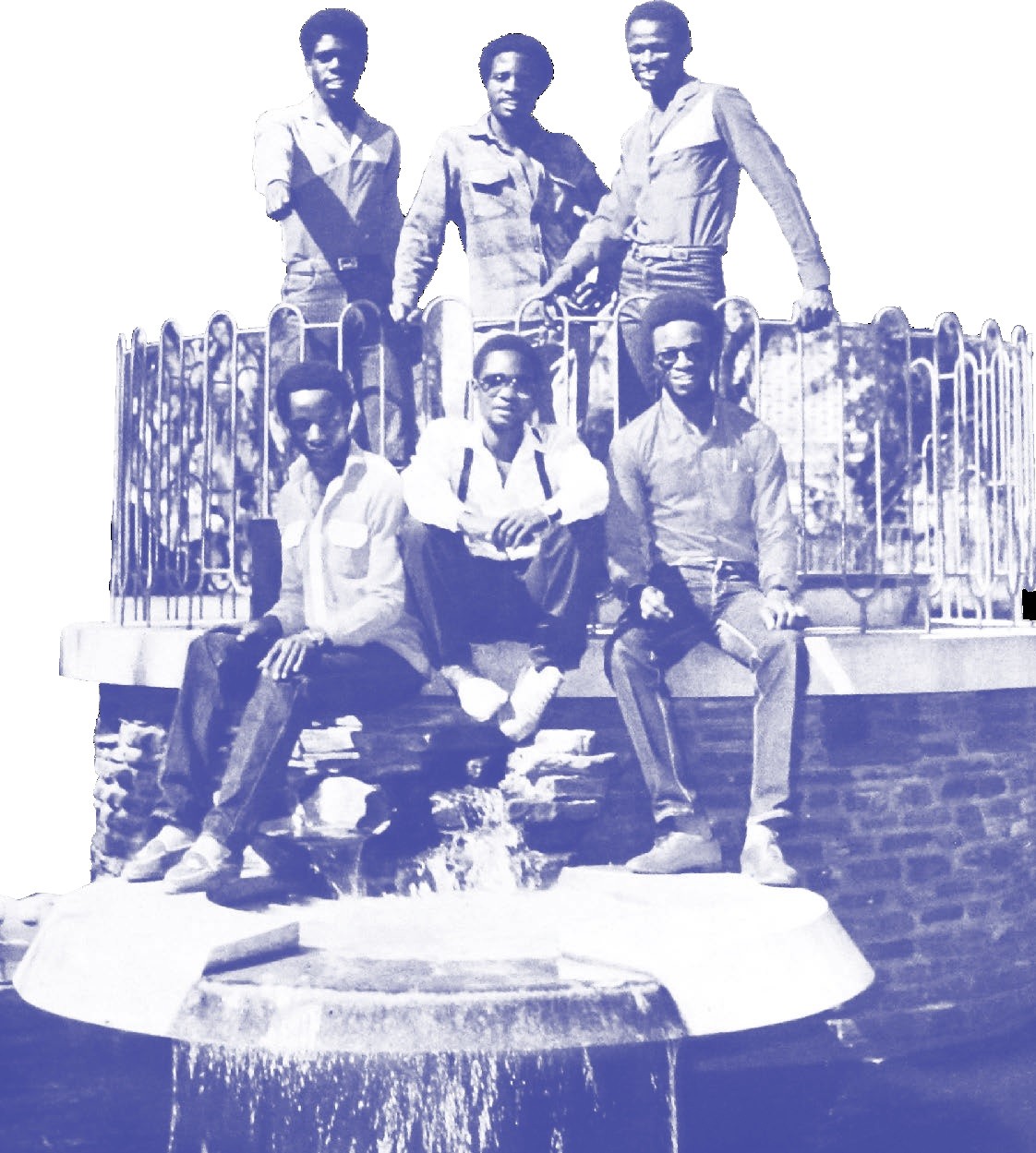

From the beginning Revue Noire was aimed at the widest possible audience: “Art lovers,” “Africa lovers,” “general readers interested in other cultures” as well as “specialists.” Distributed internationally, it was bilingual (English/French), sometimes even trilingual. This language policy and its focus on specific regions – from Abidjan to London, Kinshasa to Paris – not only facilitated access to information on African artistic production but also forged new links between artist based on the continent and those working in the diaspora.

After 34 issues Revue Noire interrupted the printing of the journal in 2001 and refocused its attention on publishing books, curating exhibitions and posting occasional online content.

traduction française par Scarlett Antonio

Inspirés par la communauté mondiale, croissante et vibrante du creuset des artistes africains et poussés par le besoin de défier les approches réduites, exotiques et ethnographiques de la culture africaine, Jean Loup Pivin et Simon Njami ont lancé la Revue Noire en 1991. Conçue comme une manifestation imprimée des arts de l’époque, elle couvre tout de l’art, l’architecture et photographie, au cinéma, littérature, théâtre, mode, citées africaines, SIDA et même la gastronomie. La conception joua un rôle clé dans la manière de transmettre ses objectives. Revue Noire était une revue de luxe, avec un bon sens de la mode et distinctivement parisienne. Aux images frappantes se joignaient des textes pour la plupart informatifs qui soulignaient des réponses artistiques à la presse internationale et aux regards touristiques; la production des discours de l’identité culturelle sur le continent; la charpente du corps africain; les citées urbaines; et changeant rapidement la dynamique entre les valeurs esthétiques africaines et les influences occidentales.

Ainsi que l’expliquait Simon Njami, “En traitant de l’Afrique et de toutes les idées préconçues que les gens ont du continent, nous voulions depuis le tout commencement utiliser le meilleur papier, la meilleure mise en page, plein de couleurs et à la taille qui ferait justice aux artistes que nous présentions. Nous avons du faire face à un double défi: à l’époque où nous avons commencé, l’art contemporain africain existait à peine. Aussi nous présentions quelque chose à une audience qui n’était pas consciente de ce qui se passait. Nous avons du, par conséquent, accentuer non seulement le contenu mais aussi l’apparence physique du magazine.”

Depuis le début, la Revue Noire visait une audience la plus large possible: “des amoureux de l’Art”, “des amoureux de l’Afrique”, “des lecteurs en général intéressés aux autres cultures” ainsi que “des spécialistes.” Distribuée internationalement, elle était bilingue (anglaise/française), quelques fois même trilingue. Cette question du langage et son centre d’intérêts sur des régions spécifiques d’Abidjan à Londres, de Kinshasa à Paris non seulement facilitaient l’accés à l’information sur la production artistique africaine mais aussi forgeaient des liens nouveaux entre artistes centrés sur le continent et ceux travaillant dans le Diaspora.

Après 34 éditions la Revue Noire cessa l’impression du journal en 2001 et centralisa son attention sur la publication de livres, la conservation des expositions et émettant à l’occasion leur contentement en ligne.

PEOPLE

Jean Loup Pivin, Simon Njami, Ngone Fall, Yacouba Konate, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Sony Labou Tansi, Cheri Samba, Xuly Bet, Patrice Tchikaya, Akoyo Mensah, Alain Mabanckou, Sokari Douglas Camp, Jean Claude Fignole, Andre Magnin, Kossi Efoui, Oswald Boateng, Yvone Vera, Jose Eduardo Agualusa, Rui Tavares, Jean-Luc Raharimanana, Georges Adeagbo, Djibril Diop Mambety

FAMILY TREE

- Accueillir, 1972

- Awal, 1985

- Diversite

- Olusum/ Genese 1989

- Ecarts d’identite 1992

- Africultures, 1997

- Sigila, 1998

RE/SOURCES

- Revue Noire on Wikipedia

- Revue Noire Website

- “Revue Noire,” Wikipedia

- “Revue noire”, “Africultures

- Editions Revue Noire at Alibris

- Sarah Nuttall, Beautiful/ugly: African and Diaspora Aesthetics, Duke University Press, 2006, p.12

No comments yet.