From the earnest hustle of our elders in writing during the 1960s to the contemporary dreams of ubiquitous hustler writers, Billy Kahora* wonders about the place of creative writing programmes.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver, describes a unique moment at the 1962 Makerere Conference for Literature that feels straight out of a creative writing workshop. His short story, “The Return”, published by Transition, is being discussed in the short story session at the conference. South African writer Bloke Modisane says: “It [The Return] lacks emotional motivation; the dialogue is used not to heighten the drama but to explain the events.”

Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and La Guma’s A Walk in the Night come under the workshop treatment in the novel session. History’s broad brushstrokes paint the conference as a political conference attended by writers. And of course as spectacle – the place that gave birth to African writing in English. But as Ngugi points out in Birth of a Dream Weaver: “But for me, a writer in his very beginnings, the most important discussions were not about philosophy and ideology but rather the specifics of texts, elements of the craft of writing.”

The same discussions were taking place in classrooms at the English Department at Makerere University. In an essay, “Makerere: The Place of the Early Sunrise”, Margaret Macpherson writes: “If students were taking minor English they were encouraged to write.” The English Department initiated a literary competition that attracted the likes of Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Peter Nazareth. There was also the Makerere Writers Club that met fortnightly at lecturers’ houses or the university canteen to talk books and writings. But of course there was all the other stuff. Ngugi highlights Lewis Nkosi’s write-up of the conference as the best possible conclusive summary of the insider’s take of Makerere 1962: “Mostly young, impatient, sardonic, talking endlessly about the problems of creation, and looking, while doing so, as though they were amazed that fate had entrusted them with the task of interpreting a continent to the world.”

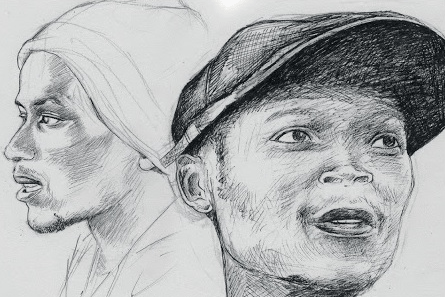

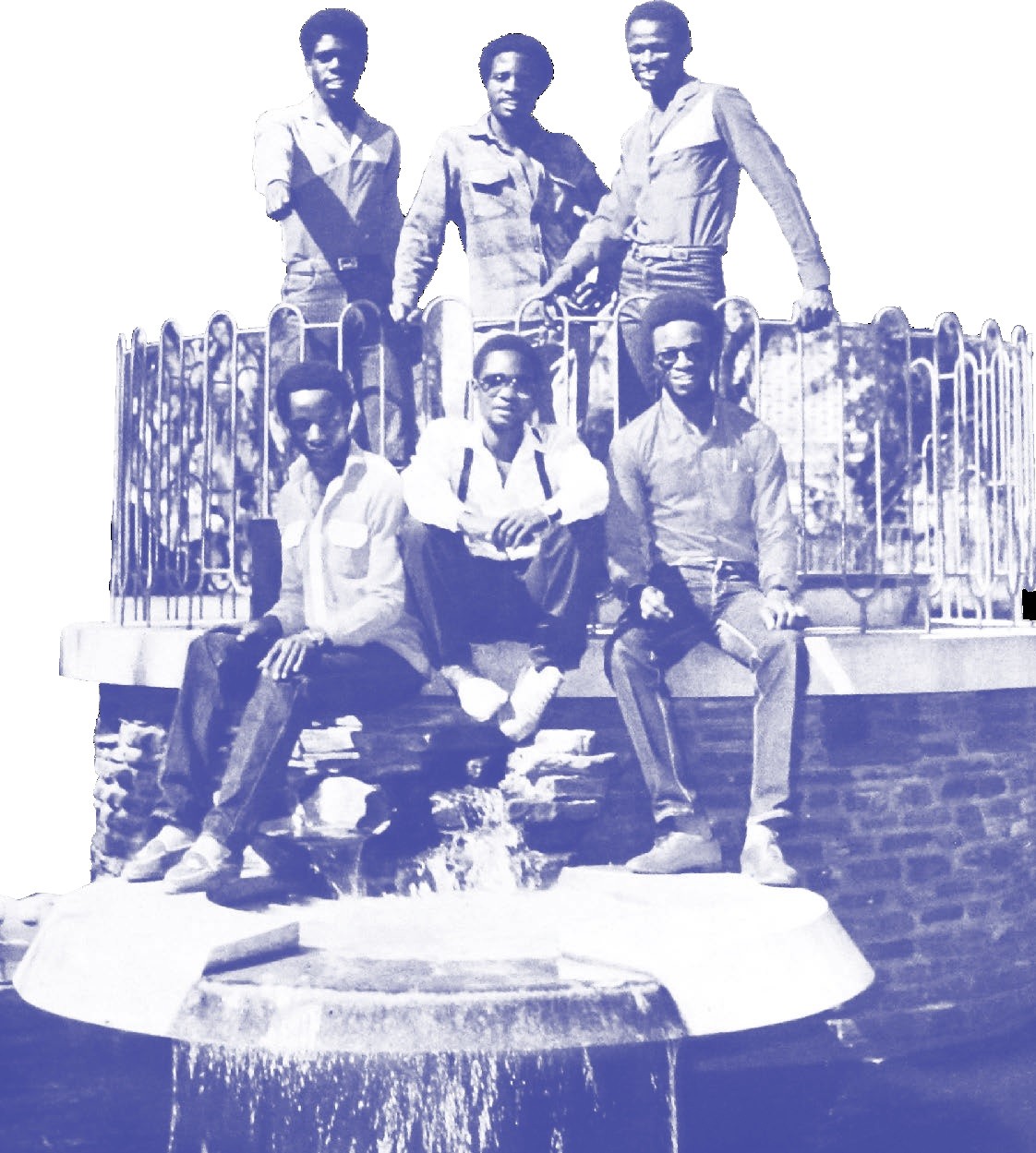

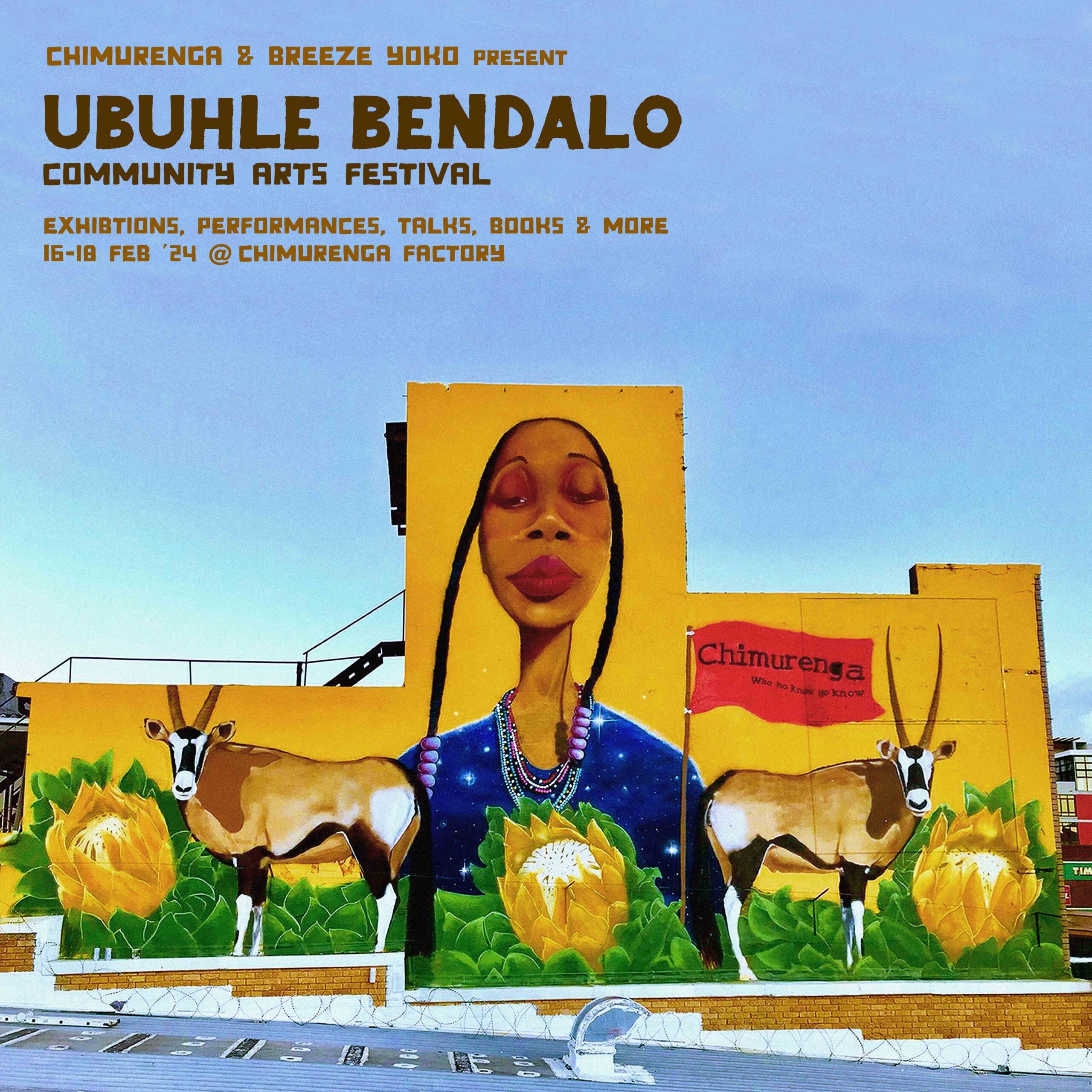

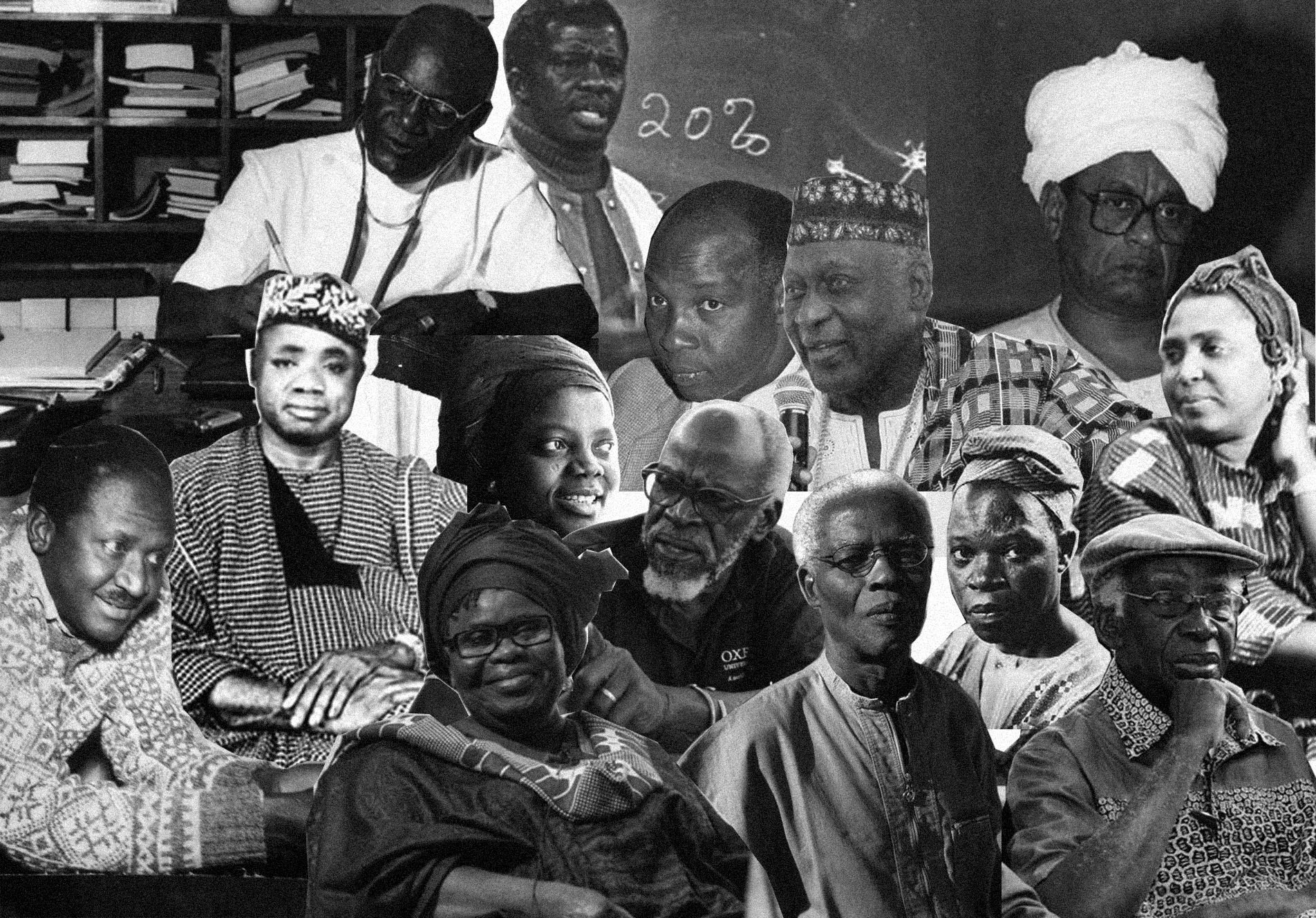

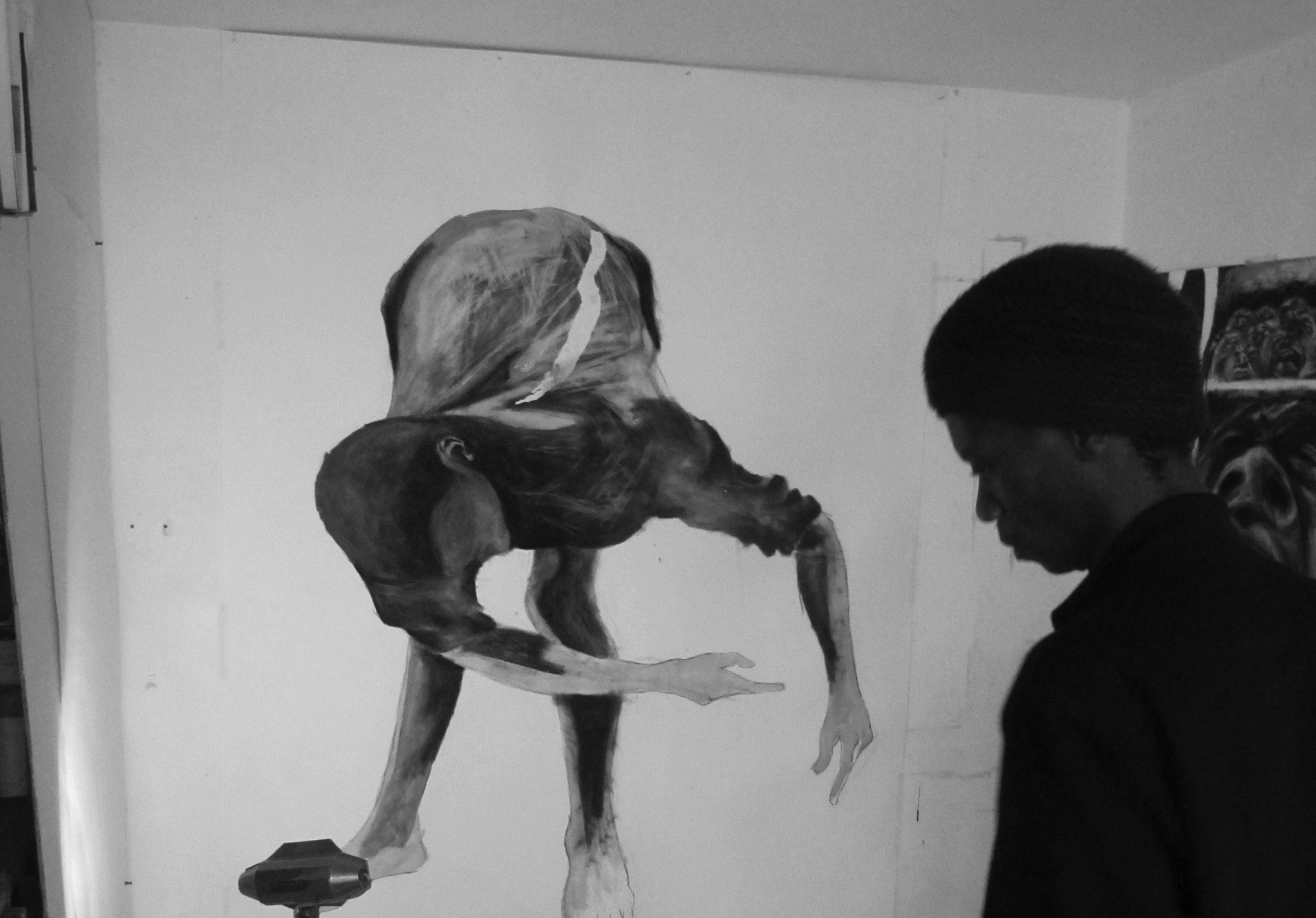

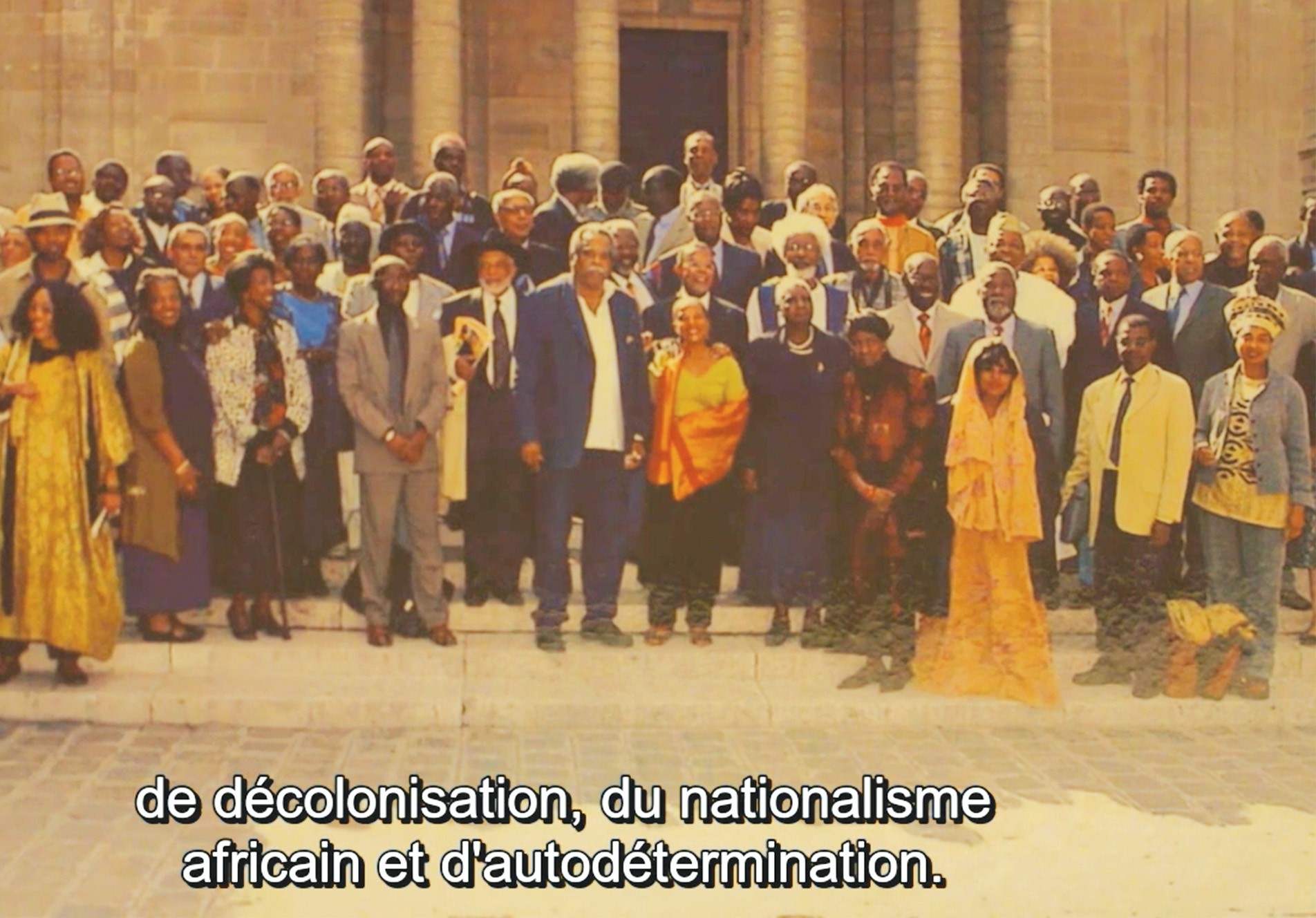

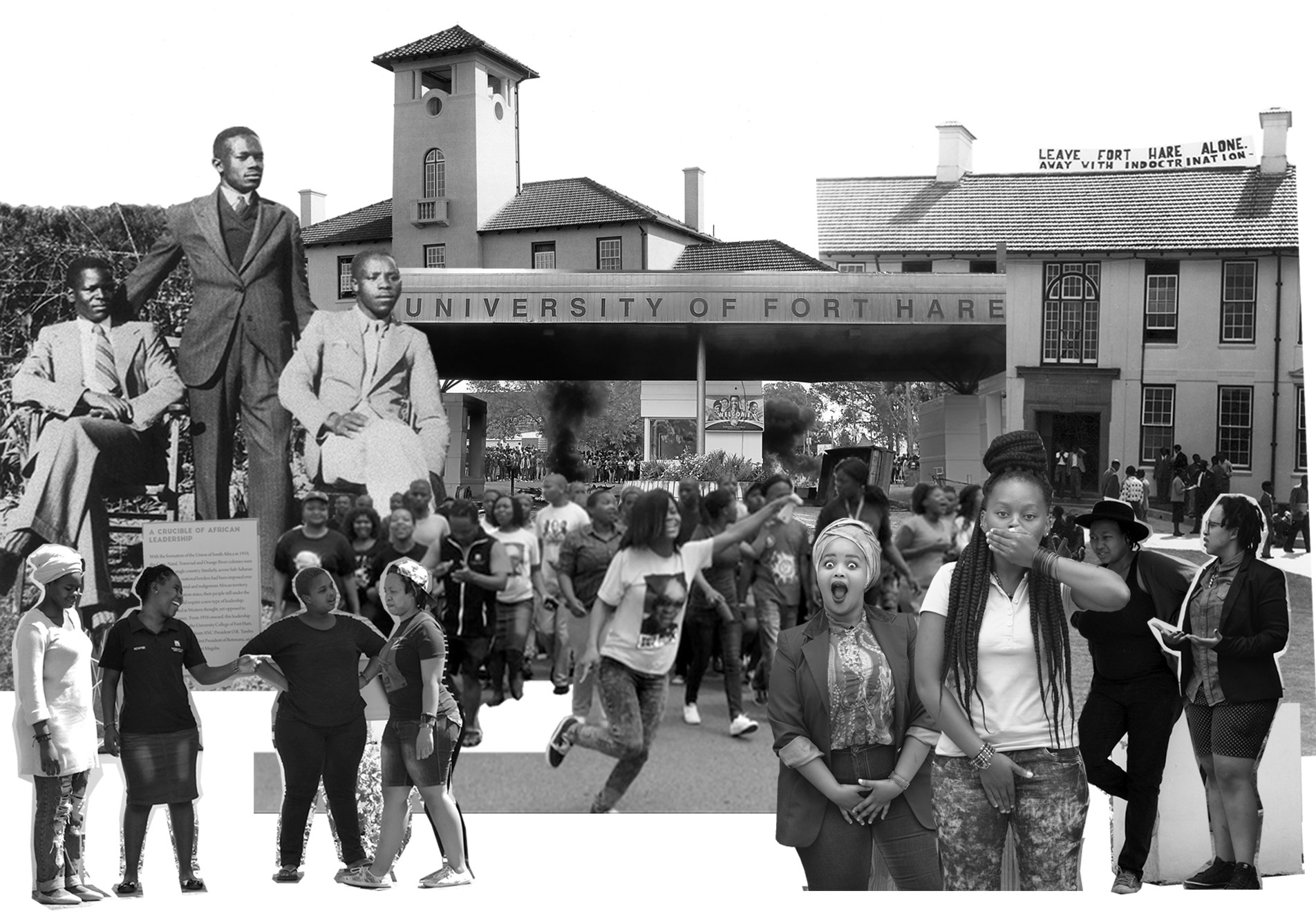

Artist impression of group photo of participants at the First Conference of African Writer of English Expression, Makerere University, 1962 (Illustration: Dada Khanyisa)

1. Gabriel Okara; 2. Rajat Neogy; 3. Bloke Modisane; 4. Chinua Achebe; 5. Okot Pbitek; 6. Bernard Fonlon; 7. Ngugi Wa Thiong’o; 8. Segun Olusola; 9. Grace Ogot; 10. Jonathan Kariara; 11. Rebecca Njau; 12. Wole Soyinka; 13. ; 14. John Pepper Clark; 15. Saunders Redding; 16. Christopher Okigbo; 17. Francis Ademola; 18. Ezekiel Mphahlele; 19. Arthur Maimane

Ngugi’s own writing journey has always prominently featured political questions rather than matters of craft, at least in public reactions. But in his memoirs and other communications, a tenuous strand can be put together. In Birth of a Dream Weaver:

“My Limuru and Kenya remain a land from which I have escaped, but I want to write about it; I want to make sense of it… I scribble a few words here and there, but nothing forms. I am upset, I have lived in a landscape of fear but I am unable to write about it… And then one night I hear a melody, then the words… so the memories come back. Then it hits me – the dedication, the collective will. That’s what I want to write about. The collective dreams for a meaningful tomorrow. The barefoot teacher was at the center of the dream. He is the interpreter of the world: he brings the world to the people; he is the prophet of a tomorrow. I want to write about this so bad, it’s like a fever that has seized me again and intensified.”

A motif that triggers the writing of his second novel, Weep Not Child, is a song. This recurs in his memories of childhood, his teenage high school years and at Makerere University. He becomes attached to the songs told in the oral stories of his childhood, the songs he remembers at Alliance High School and now the songs of collective struggle at the university. “Best for me were those stories in which the audience would join in the singing of the chorus… this intensified my anticipation of what would happen next.” He discovers through the Old Testament in Gikuyu that “written words can also sing”. His writing journey learning craft continues in his second memoir, In the House of the Interpreter:

“The King James–authorized version remained one of my favorite reads. I learned to mix the simple, the compound, and the complex for different effects. Give me some more pages, I wrote back to Kenneth. But don’t use big words. Read the Bible again and see how English is used.”

Before Ngugi left Makerere, he was already writing for the now defunct Nairobi-based Sunday Post and later he would almost join the newsroom – that other early breeding ground for this generation of African writers – but was deterred by a magnanimous British editor who advised that his craft would suffer. Nonetheless, Ngugi credits his time as an op-ed writer for the Nation for some of his literary chops by learning to write to deadline. The newsroom as a kind of craft workshop.

This trajectory continued, with Ngugi shaping his craft fluidly between the university and informal spaces. In 1967, he accepted a position at the University of Nairobi, becoming the teacher he alludes to in Birth of a Dream Weaver – not barefoot, but certainly at the centre of a dream. By 1971, he was the “first African to head a department at a university” at the University of Nairobi’s Department of Literature. It was a path that would come to define Anglophone writing in East Africa and elsewhere on the continent, as it emerged via the flow of words and knowledge between international MFA programmes and local university literature departments, the networks developed by local writers, editors and institutions, and the bold moves made by some writers based in universities to break down the division between theory and praxis in the university classroom.

MFA vs the Postcolony

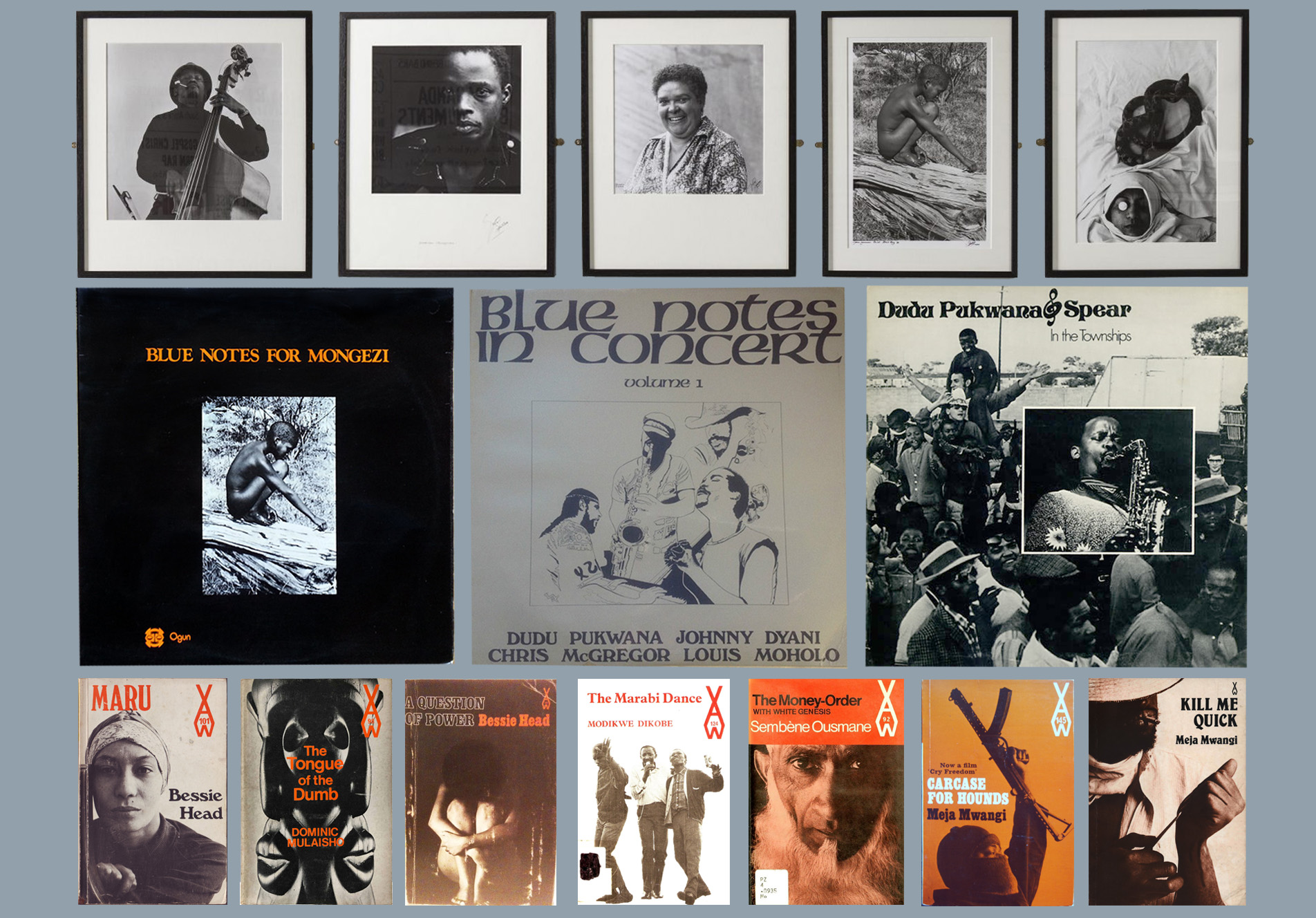

A single typewriter was the University College, Ibadan’s (UCI) first official contribution to creative writing – a meagre donation to the student literary publication Horn, founded by a British lecturer who joined UCI’s English Department from the University of Leeds in 1956. At the time, the UCI curriculum essentially mimicked that taught in London and Horn was within this ambit. Modelled on the University of Leeds’ Poetry & Audience, it relegated literary creation to an extramural activity – one that had a home in the English Department, but no place in the official curriculum. This confined its impact but it also gave it the freedom to move beyond the colonial syllabus.

The magazine, edited by a young and talented Nigerian undergraduate named JP Clark, soon became home to UCI graduates Christopher Okigbo and Wole Soyinka. After graduating, Okigbo became an active member of the writing community in Nigeria and regularly worked between the university and public spaces. As assistant librarian at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, he founded the African Authors Association. Along with Soyinka and Achebe, Okigbo belonged to the Mbari Writers and Artists Club in Ibadan, co-founded by Ulli Beier as a place for new writers, dramatists and artists to meet and read their work.

Beier was a maverick. An itinerant German-Jewish editor, writer and scholar, he had travelled from London to Ibadan in 1950 to teach at UCI. Faced with what he dubbed the colonial chauvinism of the university, he soon moved to the Extramural Studies Department outside of Ibadan. While a teacher at UCI, he travelled often and attended the First Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris organized by Présence Africaine at the Sorbonne. Inspired by what he heard, he founded Black Orpheus on his return.

The Ministry of Education in Nigeria might have sponsored the first six issues of the magazine, but the journal defiantly declared itself not just outside the academy, but openly against it. The editorial to its inaugural issue (September 1957) reads: “the primary purpose of this journal is to encourage and discuss contemporary African writing” and that, unlike UCI’s curriculum, it would include oral literature, Afro-American writing, and translations from non-anglophone African literature.

South African writer Ezekiel Es’kia Mphahlele, in exile in Nigeria, regularly published in Black Orpheus, alongside soon-to-be prominent writers like Soyinka, Gabriel Okara, Alex La Guma, Ama Ata Aidoo, and Grace Ogot. Mphahlele was also an active participant in lively debates at Mbari that would shape the immediate future of writing and how it was taught on the continent. Mphahlele went on to set up a Mbari centre in Enugu, Nigeria, under the directorship of John Enekwe.

In 1962, he joined JP Clark, Robert Serumaga, Bloke Modisane, Lewis Nkosi, Ngugi and more at the Makerere conference. The following year, shortly before Kenyan independence, Mphahlele arrived in Nairobi to establish a new Mbari centre. One of the aims of the centre was to throw open the debate of the place of African literature in the university curriculum and to drum up support for the inclusion of African literature as a substantive area of study at university, where traditionally it was being pushed into extramural departments and institutes of African Studies.

In 1971, a colloquium on Black aesthetics held at Nairobi extended this agenda. The colloquium resulted in the publication of two volumes by the East African Literature Bureau: Black Aesthetics (1973) edited by Pio Zirimu and Andrew Gun, and Writers in East Africa (1974) edited by Andrew Gun and Angus Calder. Here, the main preoccupations of the participants was not the usual literary criticism and analysis, but the creative act of writing, the establishment of a distinct East African voice, the nature of the writer’s audience and the choice of language.

Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek used the opportunity to attack any suggestion that there was a need for critical analysis, stating that “the creative and most enjoyable human activity has been reduced by interested professors into a game played by professionals according to professional rules, for which they are paid the highest salaries in East Africa.”

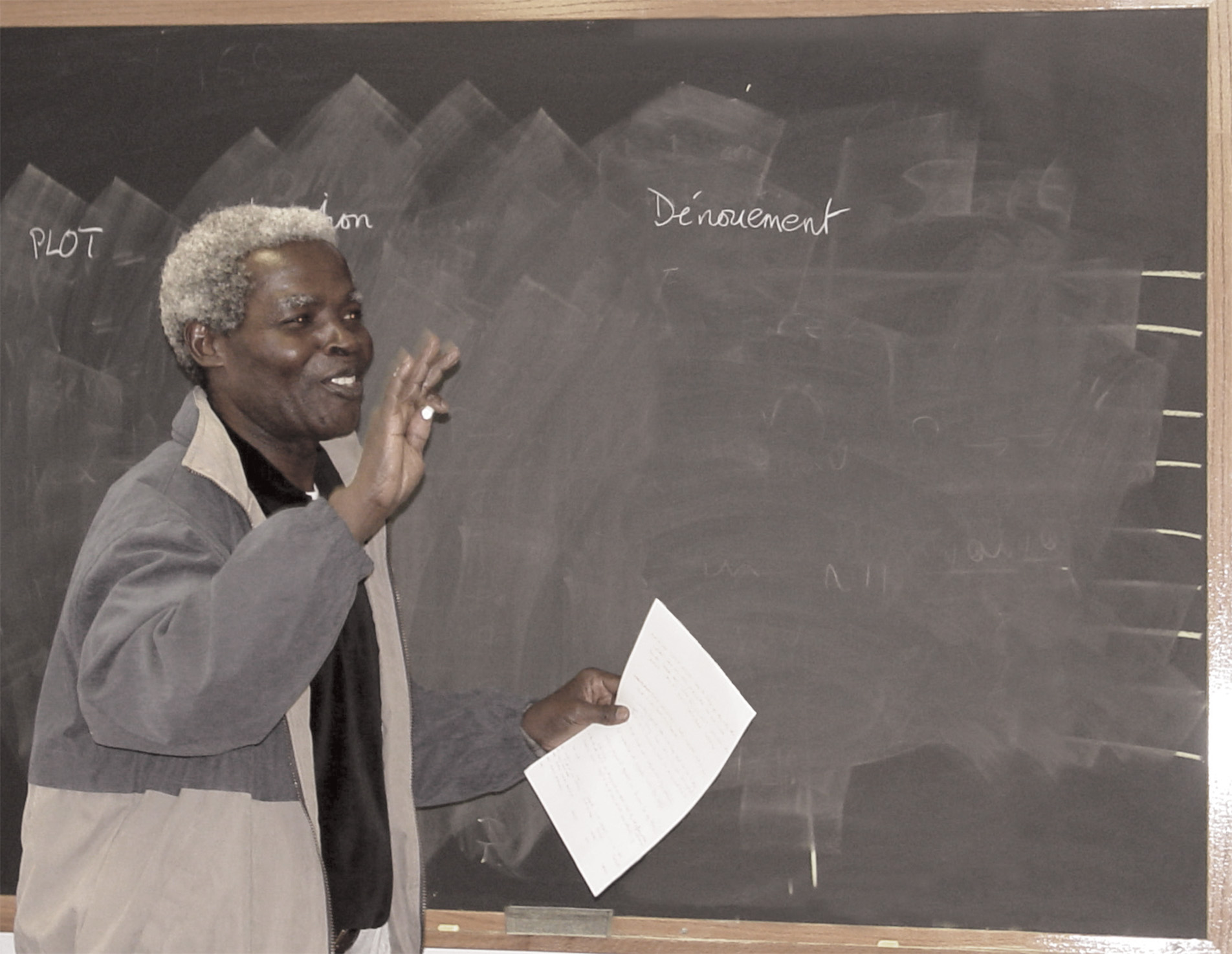

A few years earlier, p’Bitek had joined Ngugi at the University of Nairobi, after being dismissed as the director of the Uganda Cultural Centre for having criticised the government. Taban Lo Liyong, the first African to graduate from the Iowa Writers Workshop, followed in 1968. Together they managed to change the name of the Department of English Literature to the Department of Literature. A key part of this transformation was challenging the division between theory and praxis. Writing workshops were integrated into the curriculum and the examination allowed for one paper to be replaced by a piece of creative writing.

This was a dramatic shift, but Taban continued to advocate for a full MFA programme within the university: “We could say the Revolution of Literary Studies has had some success,” he wrote in 1969, continuing:

“It has introduced new topics, and new subjects, but it has not, unfortunately, produced the scholarship and scholars to sufficiently justify it… But, without having taken courses in creative writing, or enrolled in creative writing courses by correspondence, how could they hope to rise above the also-wrote! The system inherited from Britain could not have been expected to produce any better products in Africa. Only an American system of undergraduate and post-graduate programme, the type that produced me, could have done the revolution justice.”

Since this was absent at the university, Taban Lo Liyong joined a nascent group of intellectuals comprised of students and lecturers from the then Department of English and journalists who met fortnightly at the famous Paa ya Paa arts gallery founded by Tanzanian immigrant Elimo Njao.

Throughout the 1970s, Taban continued to informally teach creative writing for the pages of his numerous non-fiction books such as The Last Word (1969), Meditations in Limbo (1970) and Ballads of Underdevelopment (1976), which included provocations, notes and tips to writers wanting to shake up language and find new ways to write outside Western conventions.

The flood of creativity came to an end in December 1977, when officials in the government convinced President Jomo Kenyatta “that Petals of Blood and Ngaahika Ndeenda were ‘subversive’ and that Ngugi should be detained”. The detention of Ngugi signaled a turning point for the thriving cultural scene of Nairobi. It was followed by a mass exodus of scholars, writers, and journalists, echoing the bloody approach against writers in Uganda at the beginning of the 1970s.

Today, creative writing has yet to find its way in most anglophone public universities on the continent; South Africa is the exception with fledgling programmes at the Universities of Cape Town, Witwatersrand, KwaZulu-Natal, Currently Known as Rhodes, Western Cape, and Pretoria, and now even the new Sol Plaatje University (but even so, many of these mirror that of overseas counterparts in approach and methodology).

The continent still has its share of young, impatient and sardonic writers, but universities continue to treat creative writing largely as a hobby. Writing is left for extra-curricular spaces on campuses.

Most of the conversations about creation are happening in formal and informal creative writing workshops run by writers’ organisations on the continent and primarily in universities in the US, UK and South Africa.

Anecdotally, a quick run-through of the most prominent “informal” programmes on the continent show that characterisation, point of view, setting and description are staples borrowed from some programme in the West.

MFA vs The Hustle

Lately, most of the young writers I meet as editor of Kwani sound like aspirational entrepreneurs. They like to talk about opportunities, about platforms, are dismissive of politics, and eschew talk about the craft of writing itself. They write emails to set up meetings to talk about work they will never show you. So, when there is now work and I’m asked for opportunities, I suggest structured programmes because there is so much writing competition on the continent today. A young writer needs an edge. When I started writing seriously, the handful that were trying to do it full-time were all friends or acquaintances and had been published in Kwani. Over the years, the number of “writers” has grown exponentially. Every year I am asked to write a recommendation for another writer looking to enrol in an MFA in the UK or the US.

Recently, one brilliant young Kenyan writer I know came up to me saying he was worried that all his writer friends in Nairobi, his community, were applying for MFAs. He’d been working on his novel for the last two years and the usual signs that he was going a bit crazy were there. When I saw him now and then, he either seemed brilliantly effusive or Mathare-case withdrawn. And most times he’d been drinking. I suggested that maybe he needed to follow his community to an MFA programme. He looked existentially weary. He’d been doing Nairobi grit and I mentioned to him that he might want to take a few years off himself to attend a programme. He lit up and retorted that he did not want his writing to be Americanised. A brilliant understated writer, he was given to oral hyperbole. A week later, he asked to talk to me, his mien suggesting that there had been a death in the family. Then, he mentioned that he was in real doubts about his work and how it lacked real importance in the world.

I explained what an MFA could do that would solve all his immediate problems. He was good enough for someone to give him tuition, accommodation and then some more. His money struggles would ease up. I mentioned that MFAs also provide literary drinking opportunities and drunken sexual encounters. I did not tell him that he clearly needed a break from more practical mediocre types in his set who were making him think he was a genius. A lot of the most brilliant young writers on the continent are so comfortable in their own spaces that they are scared of going into the real test of a bigger scene that doesn’t give a fuck. I felt that in the right MFA programme he would meet other writers who came from similarly small ponds that would provide the right kind of competition. A small space can come with false reinforcement, negative enabling. The MFA programme does not lack all this, but it’s kind of different when you are far away from home. Eventually you will hide away even because of the cold, wet, dark evenings and write.

I ran into the writer recently and asked him whether he had applied to MFA programmes this last fall and he went quiet. Then, he shook his head. And said: “Oh man, I have been caught up in the hustle.” I bought him a drink and he asked: “Can you introduce me to the guys at Chimu. I want to write for them.”

“You know what you want to write?”

He laughed.

I laughed.

“Why are you laughing?”

“Just send Chimu a piece. You know their stuff.”

Now he laughed even louder. “Also, I want to talk to you about this new writer’s website I am starting with…,” he mentioned a few other writers.

That’s hustle.

*Additional research by Stacy Hardy

This piece appears in the Chronic (April 2017). An edition which aims to complicate the questions raised by food insecurity, to cook and serve them differently.

Food is largely presented as scarcity, lack, loss – Africa’s always desperate exceptionalism or exceptional desperation or whatever. In this issue, we put food back on the table: to restore the interdependence between the mouth that eats and the mouth that speaks, and to delve deeper into the subtle tactics of resistance and private practices that make food both a subversive art and a site of pleasure.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.

No comments yet.