Deji Toye looks at the legacy of arts funding in Nigeria and questions whether the longstanding trend of patronage over policy remains in the interests of the benefactors rather than the creators of the works or the wider public audience.

George Ufot had a problem, which did not start as one, but now was. He had just been elevated to the position of Director of Culture in Nigeria’s federal civil service. It was early 2010. So important was this position that, during the country’s long years of military rule, it was one of those sequestered from the ordinary line of succession and had been occupied for many years by a military officer.

What was going to make this achievement even more groundbreaking for Ufot was that it coincided with the impending consideration of Nigeria’s revised cultural policy by its highest government body, the Federal Executive Council (FEC). Ufot had been barely six years in the service when the original policy was formulated in 1988 and it had taken 14 years for anybody to even begin to consider a serious review. Since that time, cultural issues had become increasingly integrated into development discourse and concepts such as “creative economy” and “cultural industries”, new-fangled at the start of his career, were now on firmer ground. Moreover, with a modicum of respectability coming the way of Nigeria’s motion picture industry – so much so that it has acquired its own ‘something-wood’ sobriquet – there should have been no problem in convincing the government that culture now mattered.

It was therefore ironic that the matter of naira and kobo peed on Ufot’s parade. The civil service being the civil service, it turned out that until the arrival of the document at the FEC chambers, the cultural silo had not informed the fiscal silo, let alone sought the latter’s contributions to policy proposals on tax incentives for corporate contributions to the arts. And the revenue service, being the revenue service, hates people cutting taxes on its behalf. Following the all-too-expected protestations, the revised policy was returned to sender, with the clear instruction that all inter-ministerial fault lines be dealt with accordingly before the document would be entertained sometime in the future.

In reality, Ufot’s worry should have been less about whether, and more about how, corporates are supporting the arts. Nigerian businesses have always wanted to hang out with the arts, or at least be seen to be doing so. And in the absence of a government policy that prioritises and incentivises areas of arts-spend, this frolic can sometimes appear to be driven by a ‘flavour-of-the-month’ level of commitment.

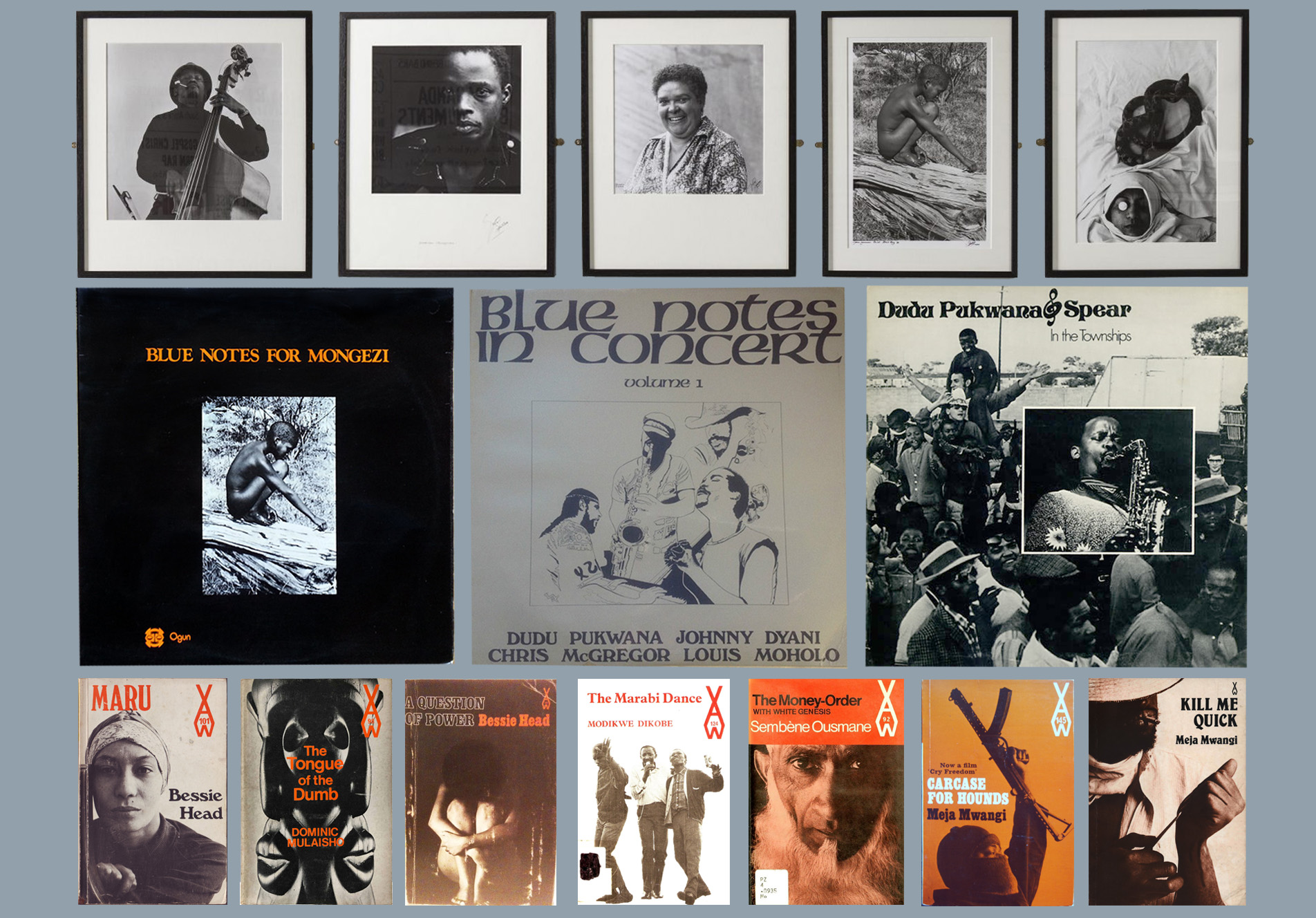

The New York Times had noted the shifting of financial support for the arts “from wealthy patrons to corporations” from the 1970s onward. By the 1980s, major Nigerian companies began something of an arts-grab. Major oil companies and banks competed for the ‘patron of the visual arts’ crown. Although the local subsidiary of Mobil, the giant American oil company, had a head-start in its collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum to launch an exhibition of ancient Nigerian art in New York, it was Standard Chartered Bank that would eventually take the throne, with its direct acquisition of some 150 works by Nigerian artists over a period of 10 years from 1989. Mobil, for its part, would become a major sponsor of Nigerian athletics. The contest ultimately set off an ‘artworks in calendars’ fad, introducing the work of a new generation of artists to the wider public.

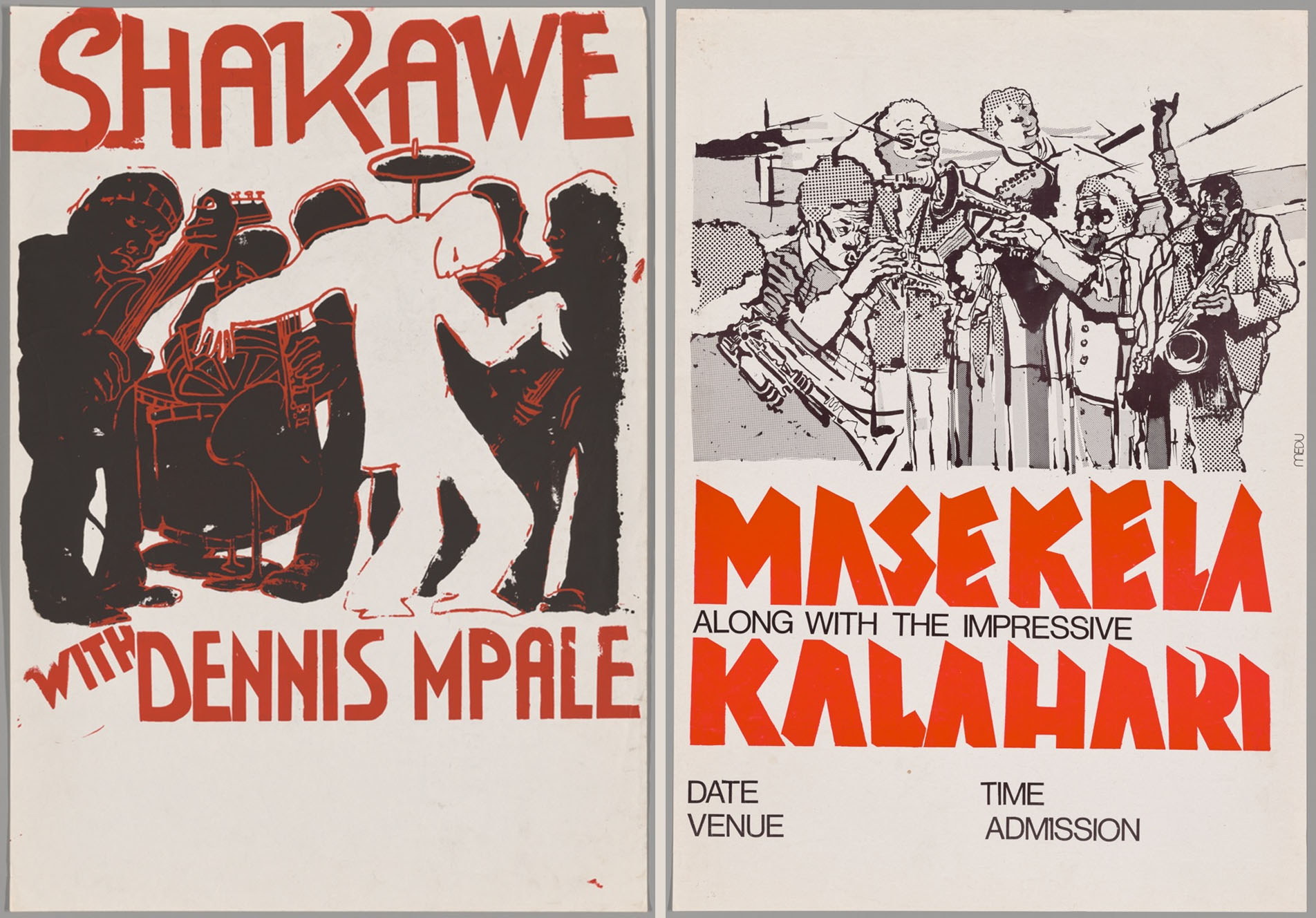

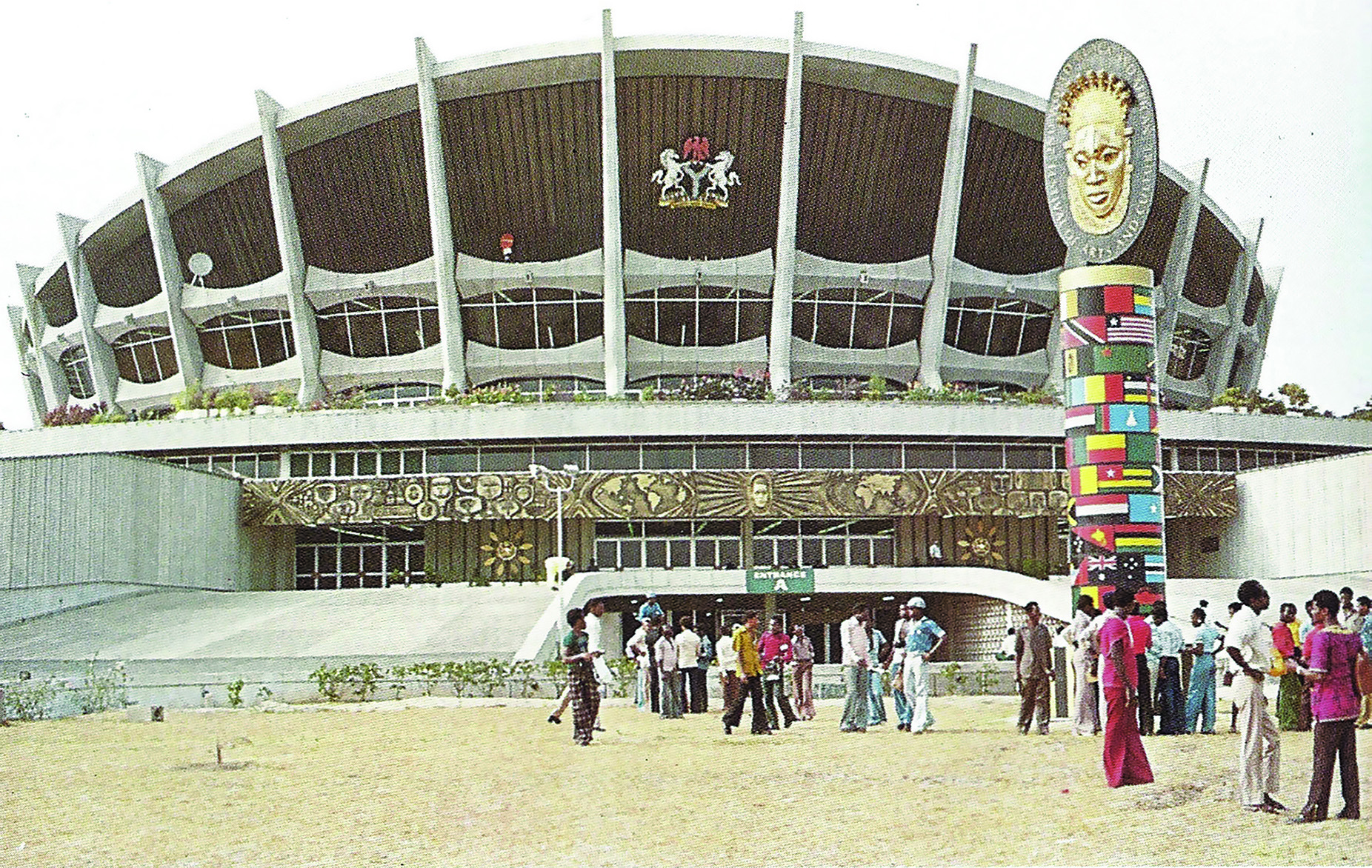

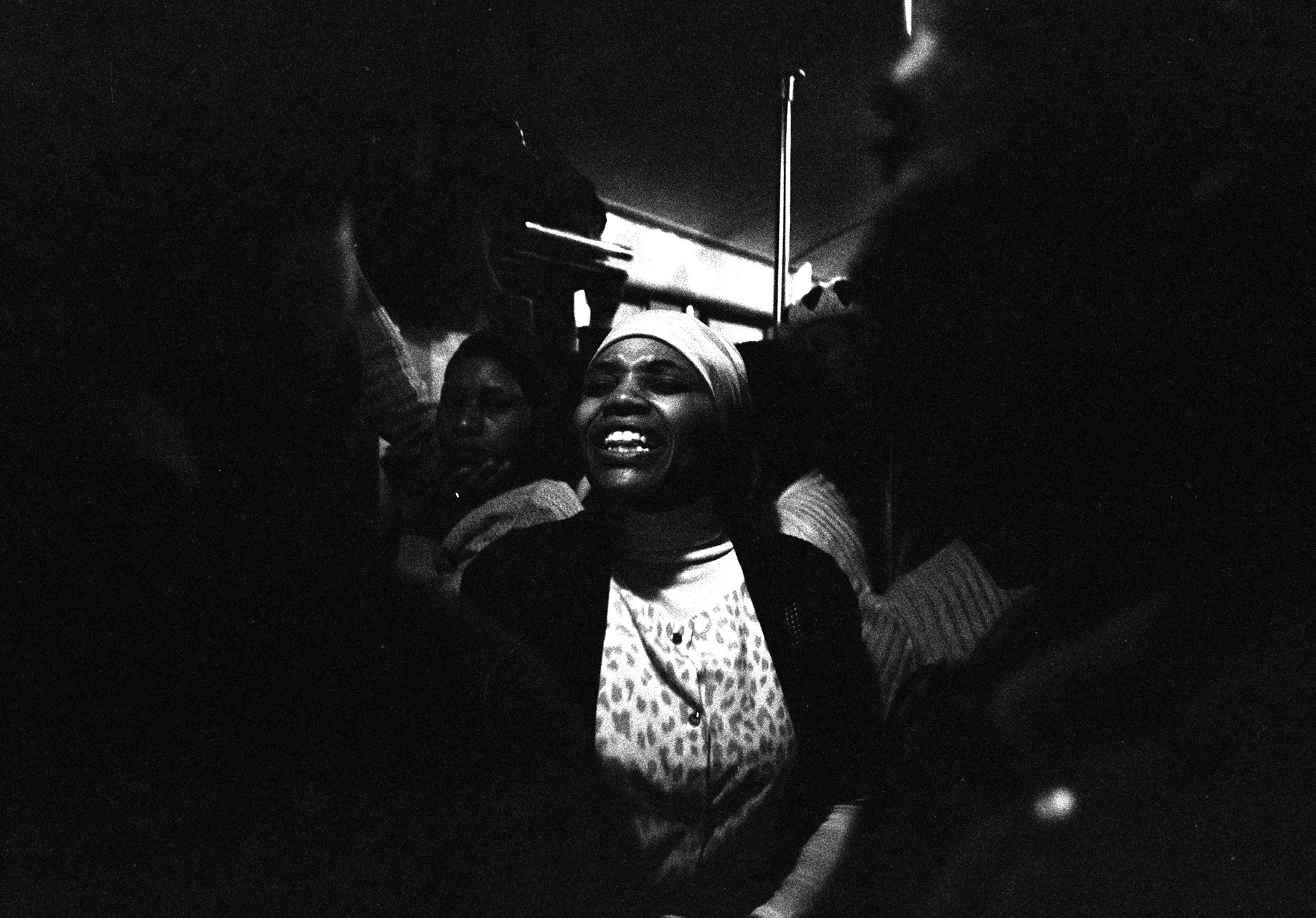

On the other hand, the trophy for the ‘theatre patron’ of the time went to another corporate, the Nigerian International Bank (NIB). With its annual drama project in the early 1990s, the bank, now operating under the name Citibank, returned the big revue to the Nigerian stage, following a hiatus of more than a decade since the hosting of the second World Festival of Black Art and Culture (Festac) in 1977.

The lasting impact of these extravaganzas on Nigerian art is doubtful though. In terms of purpose, they mostly conformed to what the New York Times article noted as the tendency of the corporate patron to favour “safe art” to the detriment of challenging, new ideas. Take the NIB drama project for example: it brought together the biggest names in the value (if somewhat rusty) chain of theatre production – an old script by Ola Rotimi, directed by himself now, or a Wole Soyinka directed by a Dapo Adelugba then. Soyinka and Rotimi had been connected with the Ife-Ibadan universities axis, which almost single-handedly developed the theatre academia in Nigeria from the 1960s onwards. Adelugba might not have been the first Nigerian professor of theatre, but his distinguished combination of scholarship and artistic adroitness in acting and directing meant that he had acquired a larger stature than Joel Adedeji, his senior and the pioneering academic in the field. Add to the mix actors who were veterans of Orisun and Ori Olokun projects, or newly redundant young turks of the more recent Ajo theatre experiment. These were the safe hands in which NIB trusted its annual revue.

In the end, the NIB project cannot be credited with charting any new direction in Nigerian theatre. Unlike the earlier, if less grandiose Ajo project, the NIB discovered no new playwrights or directors, much less actors. Ajo, a collaboration between Fred Agbeyegbe, a Lagos city lawyer, and Jide Ogungbade, a young director, had itself been a manifestation of the ‘wealthy patron’ phase in Nigerian theatre. Agbeyegbe, who made his fortune in commercial law not completely unaided by his position as a functionary of the ruling National Party of Nigeria (1979-1983), was seeking an outlet for his plays.

Agbeyegbe’s scripts could not hold a bush lamp to the works of Soyinka, Rotimi or John Pepper Clark-Bekederemo (JP Clark), or the younger Femi Osofisan and Bode Sowande, who were taking over from them in the university theatre tradition. But the project, while it lasted, brought into mainstream Nigerian theatre fresher faces, such as directors Ogungbade and Ben Tomoloju, and a generation of actors who would dominate the stage for another decade, even holding out long enough to constitute the mainframe of Nollywood once it emerged in the early 1990s. Tomoloju, himself a playwright, journalist and musician, would in particular go ahead to broadly influence the Nigerian art scene. He established the influential art pages of The Guardian newspaper in Lagos.

Nor did this phase of corporate patronage of the arts leave any lasting mark on visual art practice in Nigeria. Unlike the global Mobil collaboration with the Met, which at least worked with that museum to develop curatorial programmes around unfamiliar arts of the world, making them available to their American audiences while diversifying the permanent collection of that institution to this day, the Standard Chartered Bank acquisition did not spin any institution-building initiatives. Of course, it did put money in the pockets of artists, but that is something which the private individual collectors already did well. Despite some 150-odd acquisitions by the year 2000, the bank would never rival private collectors such as Oladele Odimayo, Femi Akinsanya, Sammy Olagbaju or Yemisi Shyllon. As the Spanish architect, Jess Castellote, noted in Contemporary Nigerian Art in Lagos Private Collections, Nigerian individuals remain the biggest collectors of contemporary Nigerian art and individual collectors often go beyond a collector’s call to take the kind of career-boosting interest in their favourite artists, such that the relationship takes on the tone of patronage.

Not surprisingly, it is these individual collectors who have now begun to think institutionally, setting up various foundations aimed at proper documentation, professional curating of shows, and organising residencies and workshops. The Omooba Yemisi Adedoyin Shyllon Art Foundation (Oyasaf), for example, initiated a fellowship programme in 2009 that sponsors graduate-level study in Nigerian art by international scholars. The proprietor, Yemisi Shyllon, himself recently co-edited Conversations with Lamidi Fakeye, a major publication on the works of the famous carver. He is perhaps the largest donor to the collection of outdoor sculpture at the Freedom Park, a project of the Lagos State government which has seen an old colonial prison in the commercial district of Lagos Island converted into a cultural centre.

Other collectors who have published major documentary work on their favourite artists, or their collection, include Okey Anueyiagu, whose 2011 book, Contemporary African Art: My Private Collection of Onyema Offoedu-Okeke, documented the largest collection of the artist’s work by any single individual, and Femi Akinsanya, who sponsored the publication of Making History: African Collectors and the Canon of African Art, edited by Sylvester Ogbechie and documenting one of the largest private collections of traditional Nigerian art.

The Sammy Olagbaju Charitable Foundation might not be as active as Oyasaf at the moment, but then, Olagbaju is a major founding spirit, and current chairman, of the Visual Art Society of Nigeria (Vason), which is bringing together the efforts of these private collectors with a permanent gallery now opened at Freedom Park. In addition, he sponsored the Castellote publication, which is perhaps the single most eloquent tribute to the role of private collectors to date.

Other institution-building initiatives include the Yusuf Grillo Pavilion established by the perennial public office holder, Rasheed Gbadamosi, at his home on the outskirts of Lagos and named for some of the pioneers of Nigerian art, the Zaria Rebels. The rebels were a group of pioneering students in Nigeria’s oldest school of higher art education, who, in the early 1960s, broke ranks with their European teachers and the official curriculum and went ahead to establish the major schools of art in various Nigerian higher institutions. The Pavilion’s annual event operates as a form of retrospective of the works and careers of major Nigerian masters, many of them members of the rebellion or their direct protégés.

Yet, none of the foregoing is meant to propose the ‘wealthy patron’ as an answer, even a placeholder, for the still yawning gap in corporate support for the arts in Nigeria. For one, some of the above-mentioned initiatives have the potential to be self-serving and, as noted by the curator Bisi Silva in the Castellote book, often reek of the overweening hegemony of the private art collector in the Nigerian art scene. Silva, the artistic director of the radical Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (CCA) and a juror of the 2013 Venice Biennale, has noted that the implication of this hegemony has been “the commodification of art at the expense of experimentation or of conceptual depth”. Any wonder that avant-garde careers such as those of Segun Adefila in theatre, or Jelili Atiku in conceptual art, have benefited so little from both wealthy patrons and corporate sponsors, in spite of the best efforts of Adefila’s Crown Troupe of Africa and other institutions like the African Artists Foundation and Silva’s CCA?

Business is looking up

In spite of what might be suggested by the influence of the wealthy patron on Nigerian art for the last three decades, the reality is that the seed of a new era of corporate giving was already being planted by 1989. This was when a group of industry leaders, who had themselves been wealthy patrons, launched a fund for the building of a cultural centre in Lagos. Bonded under the aegis of the Music Society of Nigeria (Muson), the group included Akintola Williams, Nigeria’s first chartered accountant whose firm remains the Nigerian affiliate of Deloitte & Touche, the late Ayo Rosiji, who straddled Nigeria’s political and corporate terrain for some 50 years before his passing in the year 2000, and Louis Mbanefo, a scion of the pioneering family of lawyers from the east of the country. Raising N143 million within some four years, the Muson Centre was opened in 1994. The majority of its funding has come from corporates and its two most important halls have been named after large oil companies.

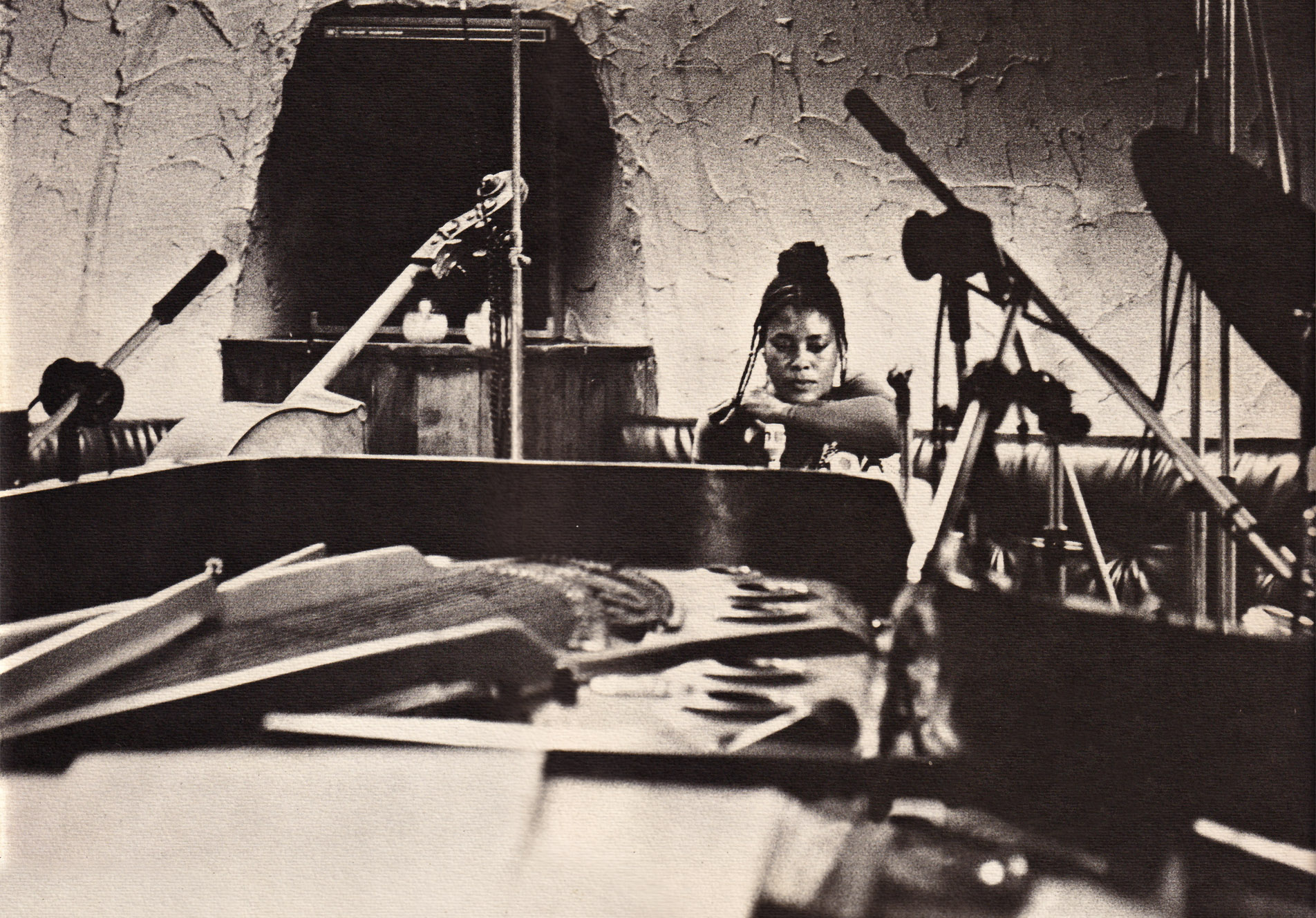

Although primarily dedicated to the promotion of music, especially classical music, the centre hosts anything from genteel recitals to popular concerts. The Muson’s music school, located in the centre, awards internationally recognised diplomas, while its annual festival embrace diverse disciplines of arts. Its official programme might be elitist and reflect some of the conservatism for which corporate sponsorship is already notorious, but its halls are available for hire to independent cultural producers.

This would include producers such as the lawyer-turned-director, Wole Oguntokun, regarded in some quarters as the most prolific theatre producer-director in the country today, and whose career has been incubated in the Muson space. By the early 2000s, with the gradual fall into decay of the National Theatre in Lagos (built for Festac 1977), and due to the increased campus violence which made the venue at the University of Lagos unattractive for theatre going, the Muson Centre was the de facto national cultural centre.

The example of the Muson Centre has something to say for the limitations of the ‘wealthy patron’ tradition and the possibilities of collaboration with corporate patrons in sustainable, programmatic promotion of the arts. It started at about the same time as the Ajo project, and another important theatre project of the time, the PEC Repertory theatre. The PEC Rep was established by J.P. Clark and his wife, Ebun, to try the repertory theatre tradition in Nigeria. It was housed in an old, disused hall leased from a sleepy trust which had managed the property on behalf of the government for a couple of decades. Using the subscription model, the well-connected Clarks had been able to enlist a circle of the Lagos elite to subscribe to seasons of performances in advance. Whatever their relative successes were, both the PEC Rep and the Ajo experiments were to wind down after a decade or less.

The Muson is no doubt a lesson for patrons in other disciplines of the art. The folks in visual arts at least have taken that lesson seriously with the formation of Visual Arts Society of Nigeria (Vason) in 2006. Gbadamosi, a founding member of the group, was a past chairman of the board of trustees of Muson. The Vason has promised to build a museum and art centre of its own.

But even without being seduced into grand projects on the scale of the Muson Centre, corporate patrons are becoming more programmatic in their giving to the arts. Take the example of the Nigerian Prize for Literature established in 2004 by the country’s leading upstream gas company, Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas Limited (NLNG), alongside another national prize for the sciences. With the prize money of US$100,000, NLNG attaches superlatives like “highest” and “most prestigious” to the description of its literary prize. Nigerians may pay more attention to the Caine Prize for African Writing, but when one considers that the UK-based prize, covering the entire continent, is worth one-tenth of the NLNG prize, the growing draw of the latter is understood.

The NLNG prize seems to have restored the crystal shoes to a discipline of the arts which was, for some time, the Cinderella of the lot. During the 1980s and 1990s, literature was the scorched patch. Nigerian writers, through the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), awarded themselves what passed for the only respectable set of prizes at the time. The collapse of the book industry chain meant that most of the benefits of a reward system were absent. Prize moneys often went unredeemed, even where prizes had been named after sponsor corporations, and although prizes were often awarded to unpublished works, these winners remained unpublished for years thereafter. Also, with the absence of the agency role of strong local publishers, a whole generation of Nigerian writers remained under the international radar. Helon Habila’s winning of the second Caine Prize in 2001 marked a symbolic return. Nigeria has dominated that prize ever since.

Citizens’ initiatives such as that of the Committee for Relevant Art (Cora), the organisers of the Lagos Book and Art Festival, were instrumental in placing literacy and literature at the centre of national discourse even through the difficult periods. So much so that, by the early 2000s, a crop of Nigerian professionals began to put their money where their rhetoric had previously sufficed, by establishing publishing houses whose focus was on creative works, even when there was little prospect of making significant profit. Muhtar Bakare, a banker, is behind the Farafina imprint, which is representative of this new attitude.

All in all, what NLNG did was to make the promotion of literature attractive to the corporate patron. Institutions like Fidelity Bank and Farafina Trust have worked with Habila and the novelist, Chimamanda Adichie, to carry out writing workshops for young Nigerian writers with measurable results; some participants have gone on to make the shortlist of prizes such as the Caine. Other industries, from telecommunications to breweries, continue to deepen their footprint in the promotion of literacy, reading and education.

And Business says to the Arts: “Can we do business?”

The institution that surely takes the cake for investing in the arts is the Guaranty Trust Bank (GTB). Its commercial investment in the Lagos art centre, Terra Kulture, charted a new course that has brought the mantra of “trade not aid” from international development discourse into the relationship between corporation and art in Nigeria. Terra Kulture is a centre for cultural production and a thriving business. Its average annual growth rate of 65 per cent between 2009 and 2011 won it a place in the top 50 Nigerian businesses, as noted by the Tony Elumelu Foundation and AllWorld network, an organisation co-founded by Michael Porter, the Harvard strategy professor.

In terms of programming, Terra Kulture does not only rival the Muson Centre, but also has created a more liberal space where more experimental art, from spoken word poetry to fashion and stand-up comedy, can thrive. It was in its hall that Segun Adefila finally resurrected the repertory theatre culture in Lagos in 2006, with his monthly show, Buk-art-eria. The organisation’s Theatre@Terra, in which different directors take turns to stage weekly productions, has run since 2007 and must now take the crown for the most number of scheduled productions hosted by any theatre in Nigeria outside of the academic setting.

The success of GTB’s commercial investment has not derogated from its charitable giving to the arts. In 2011, the bank announced a partnership with Tate Modern in the UK which, as it told its shareholders at the end of that year, is “aimed at promoting different genres of African Art to global art communities”. Specifically, the collaboration creates a dedicated curatorial post at the Tate to focus on African art and to establish an acquisition fund to enable the Tate to increase its collection and annual African art exhibition programmes. In short, the GBT-Tate collaboration may yet do for African contemporary art what the Mobil-Metropolitan collaboration did for traditional Nigerian art 30 years ago. In 2012, more than 60 per cent of the GBT’s budgeted funding to the arts was directed at the Tate project.

The late Tayo Aderinokun, the bank’s former CEO, had in fact been so bullish about corporate giving to the arts that he had co-founded, and was chairman until his passing in 2011, the Art & Business Foundation (ABF). The ABF, now chaired by the Ghanaian-born Lagos corporate lawyer, Myma Belo-Osagie, helped to set an agenda for corporate giving to the arts in Nigeria. Its premier project, funded ironically by foreign grant from the Ford Foundation, is the resuscitation of the National Museum, Lagos.

The medicine for the culture administrator

The GTB-Tate pact is illustrative of what is currently wanting in business support for the arts in Nigeria. Even with the best intentions, misplaced priorities can result in a mismatch between spending and impact, with unintended consequences. For example, one would have preferred a situation in which GBT had directed its institution-building gift toward the Nigerian museum, the pet-project of its late CEO, rather than a British counterpart.

Nigerian art is currently on the surge internationally. Bonhams, the UK auction house, has run an annual sale of African contemporary art since 2009. As is to be expected, Nigerian entrepreneurs are also not completely oblivious of the developments. From a one-off auction in 1999, Nigeria now has two established auction houses, hosting between two and four sale events per year. Robert Mbonu, a Lagos banker and a collector, recently launched the Art Exchange project, which, as he recently told Omenka, a Nigerian art and lifestyle magazine, is aimed at further unleashing the financial value in Nigerian art works by transforming “prized works of art by masters and legends from mere decorative pieces to art assets”.

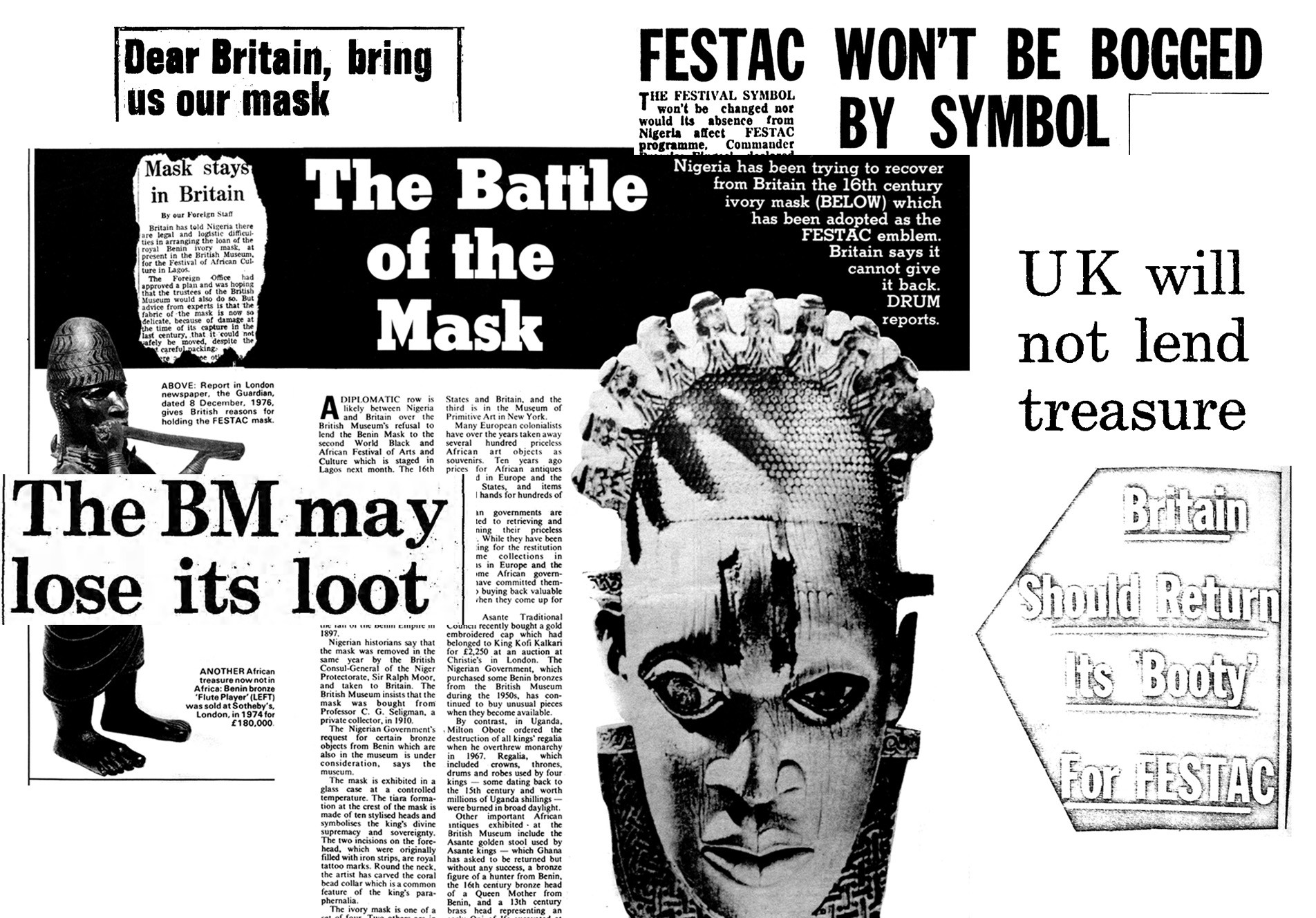

These different dynamics, working together, may result in a situation whereby the most important contemporary Nigerian works of art will only be viewed in western museums and galleries. This is already the fate of the most iconic works of Nigerian traditional art, from those of the ancient Ife and Benin traditions to the early 20th-century carvings of Olowe of Ise. This trend could be reversed if strong policy redirects business impact on the arts in the direction of strengthening Nigerian public and private institutions to acquire the choicest of Nigerian arts.

This should be the concern of George Ufot as he takes the typically long and tortuous walk toward presenting a further revised, draft policy to the government.

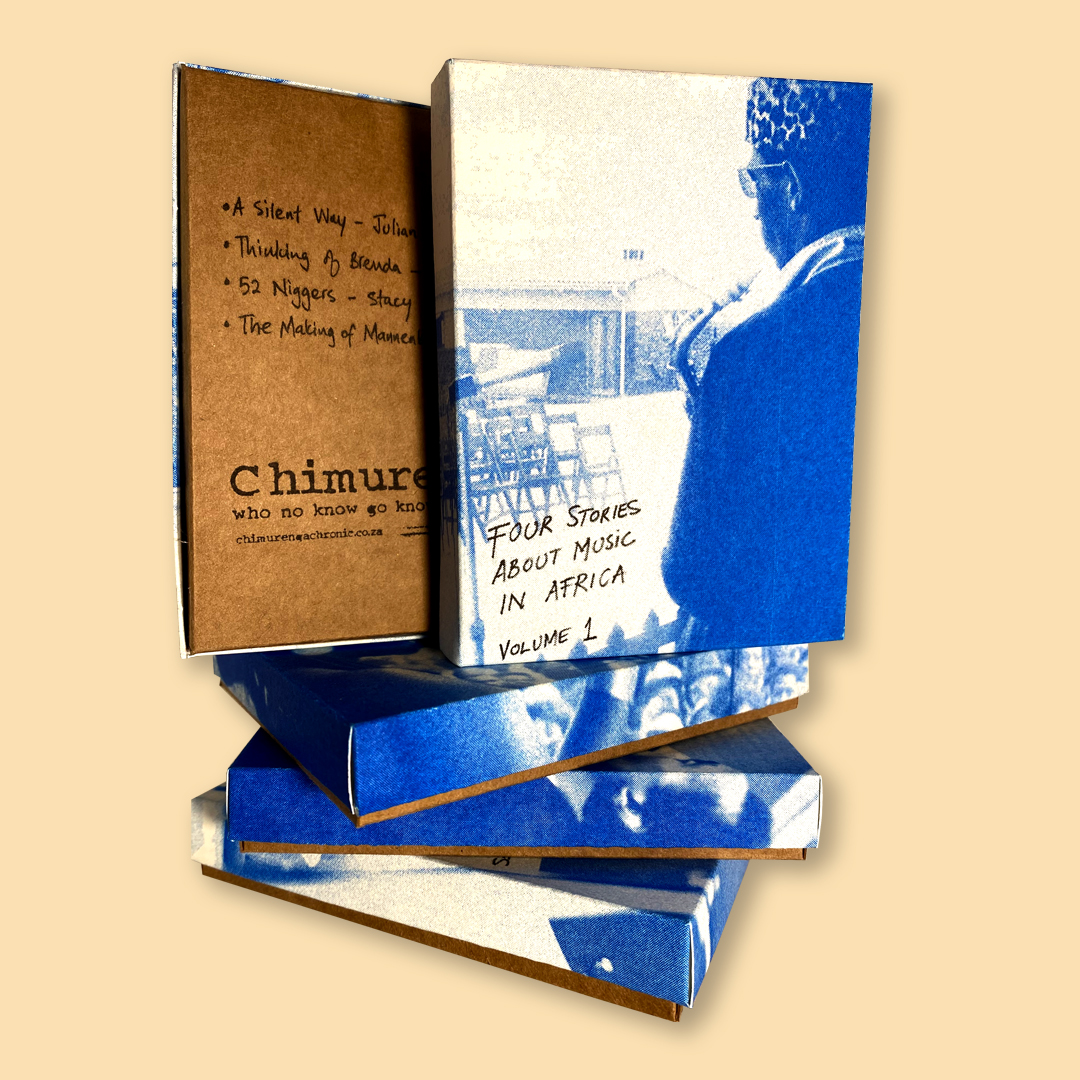

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

This article was originally published in the Chronic (March 2013).

In this issue, artists and writer from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states. To read the article in full get a copy in our online shop or visit your nearest stockists.

No comments yet.