14 November 2017. News breaks of a coup d’état underway in Zimbabwe. Tanks, armoured vehicles and military personnel are seen patrolling the capital, Harare. The images send shock waves through social media, traditional broadcast news networks and diplomatic channels. After nearly four decades at the helm, President Robert Gabriel Mugabe, Commander-in-Chief, is set to be deposed by his own army, the Zimbabwean Defence Force. Before the month is over, Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, is ushered in as the country’s third president.

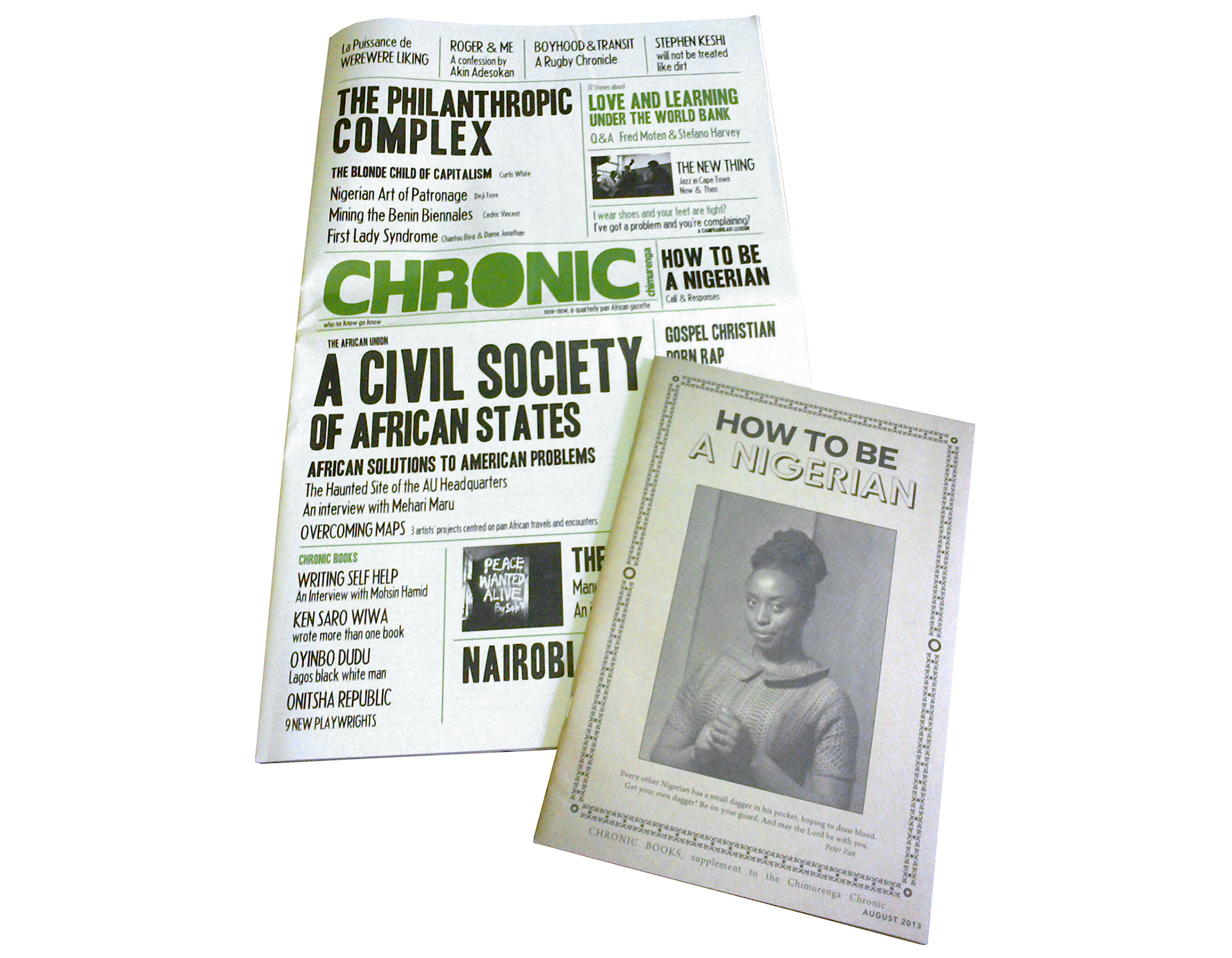

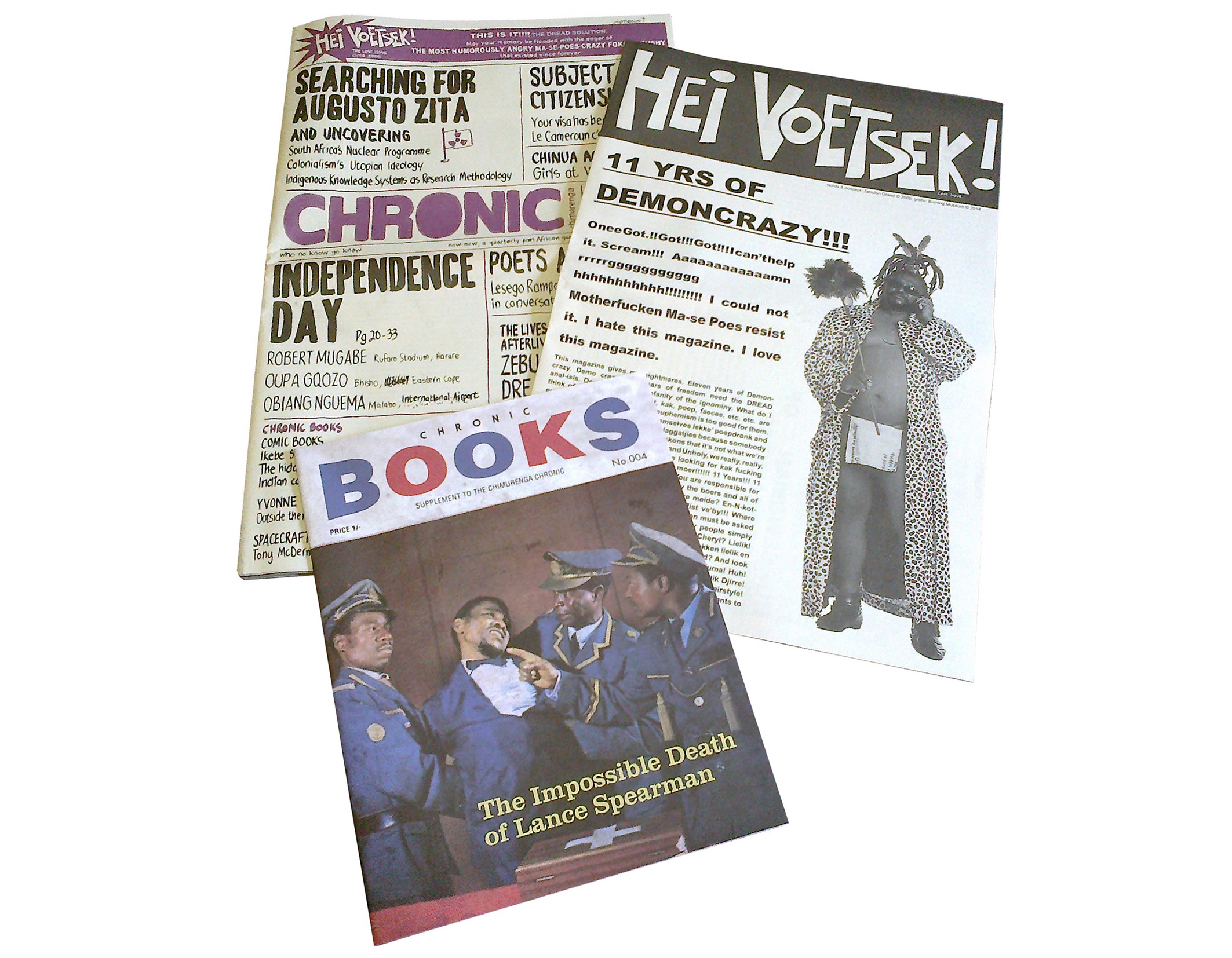

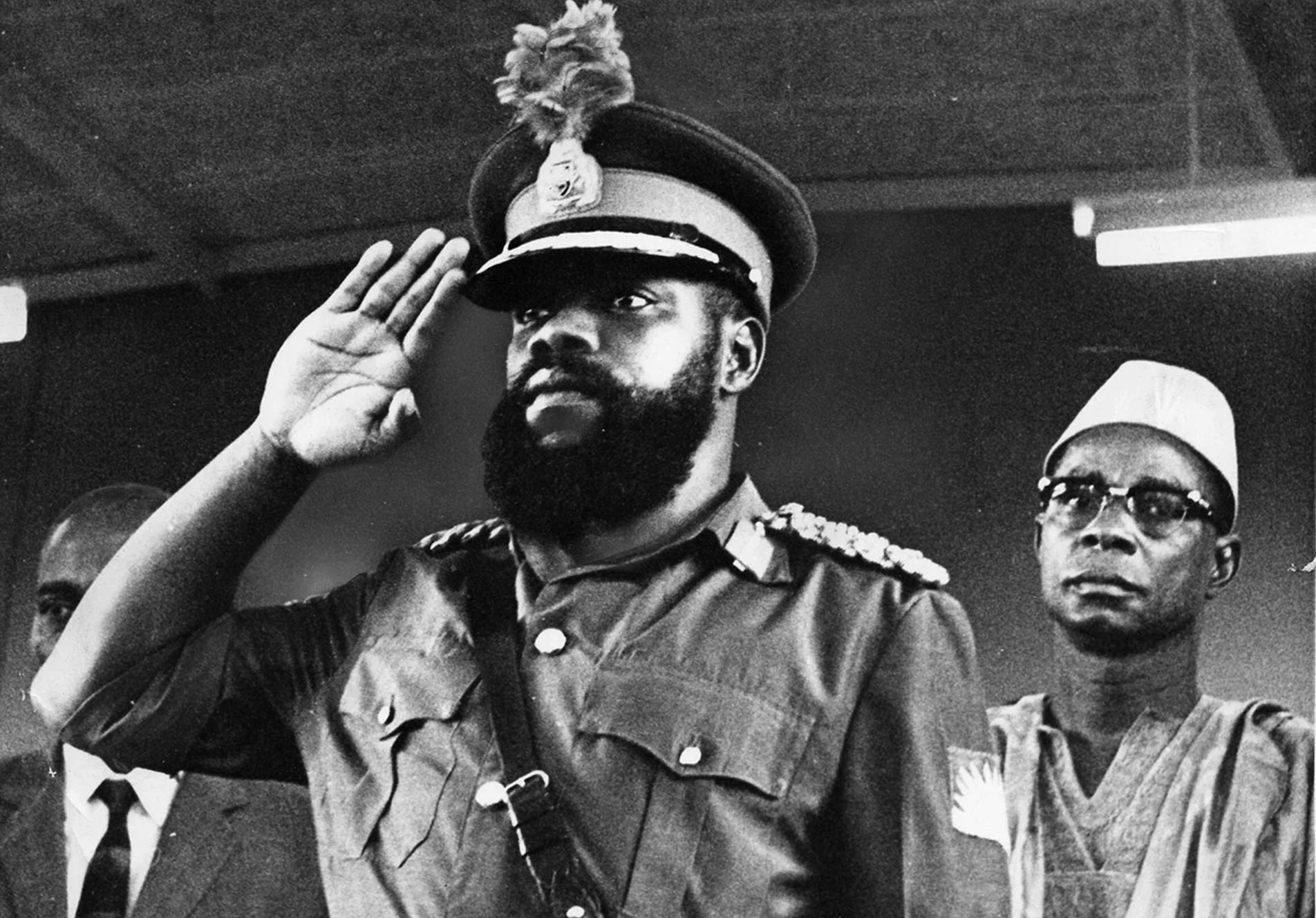

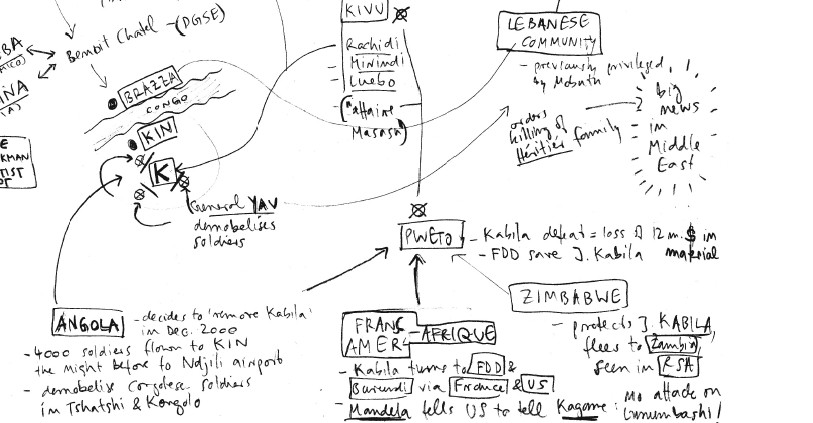

The events last November form the backdrop of the latest issue of Chimurenga’s pan-African gazette, the Chronic. The issue sits at the intersection of two separate research projects that Chimurenga have been developing since 2015. One on new cartographies, which asks the question: what if maps were made by Africans, to understand and make visible their own realities and imaginaries? And a subsidiary project, ‘Who Killed Kabila?’, where the assassination of DRC President Laurent-Désiré Kabila in 2001 serves as the starting point for an in-depth investigation into power, territory and the creative imagination.

Zimbabwe and the countries bordering it share a complex history of solidarity, conflict and cultural, social and economic exchange, but this relationship is often skewered in the media. Zimbabwe is largely written about and represented through – in relation or comparison to, and by – the region’s economic super power, South Africa. This provides a distorted view that locks Zimbabwe in a logic of emergency, and fails to capture the realities of the lived experience, or the complexity of relations between South Africa, and the bigger story of the region and indeed the continent.

Chimurenga, an innovative platform for free ideas and political reflection about Africa by Africans, is itself partially a product of this history. Founded in 2002, and primarily based in Cape Town, it takes its name from a Shona word from Zimbabwe, which loosely translates as (revolutionary) struggle, referring to both freedom struggles and Zimbabwean rebel music. This edition of the Chronic brings together voices of journalists and editors, writers, theorists, photographers, illustrators and artists from the country to tell a different story of Zimbabwe, now and in history, and to dream new futures.

In its pages, Bernard Matamboreturns to the moment of Mugabe’s deposition, listening closely to the rumour mill to grasp the intrigues of factional politics within Zimbabwe’s ruling party, ZANU PF, the mistrust and ambition which led to the change of power. Economist, Simbarashe Mumera, boards the night vendor bus from Harare to the border town of Musina and reveals how foreign companies, especially South African retailers, continue to make a handsome profit from Zimbabwe’s ongoing economic crisis.

The story of politics and economics in Zimbabwe cannot be told without the music that has driven, documented and revolted against it. In deliberate attempt to use music archives in the writing of contemporary history, Ranga Mberi travels back in time to the 1980s and 1990s, the heyday of sungura music. Dubbed the “authentic sound of Zimbabwe”, sungura weaved together Congolese rumba with Zimbabwean jiti and Tanzanian kanindo to capture the essence of life and the national mood in Zimbabwe during the best and worst times in its history. Similarly, Percy Zvomuya delves into the history of reggae in Zimbabwe, charting a web of influences that makes up not only the s

onic cartography of a revolution fuelled by chimurenga music and reggae, but which are the very groundations of today’s Zimdancehall.

Elsewhere, writer Marko Phiri and photographer Dwayne Kapula look at the history of the ‘Big Dance,’ Gule Wamkulu, a performance that dates back to the Chewa Empire of the 17th century, in what is today’s Malawi, while singer/songwriter Netsayi Chigwendere sits down with legendary poet, Chirikure Chirikure.

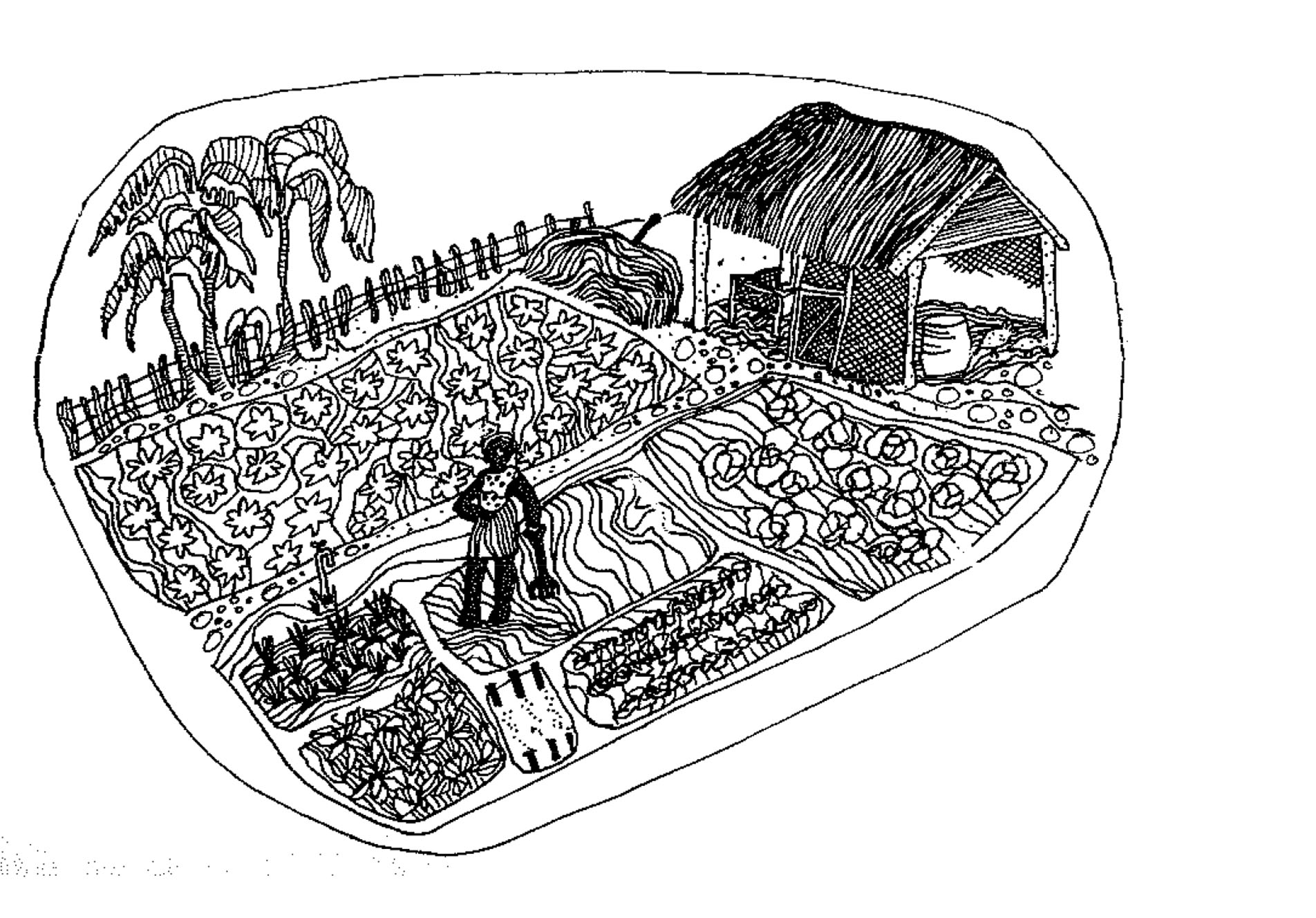

Then, Panashe Chigumadzi travels to the rural Zimbabwe of her ancestors to discover that the land reform programme that drives agricultural transformation and justice for dispossessed Africans carries with it the promise of a future, and the pain and patriarchy of the past. Florence Madenga also travels back and forward in time. Through a visit to her ailing grandmother, she reflects on the silences that live in the folds of family – the feigned dignity, nostalgia, and denial that are championed as resilience in the midst of ruin.

Other contributors to the broadsheet include Brian Chikwava, Rudo Mudiwa, Bongani Kona, Farai Mudzingwa, Nora Chipaumire, Tinashe Mushakavanhu, Nonstikelelo Mutiti, Jekesai Njikizana, Melanie Boehl, Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Zenzele Ndebele, Mike Mavura and Robert Machiri.

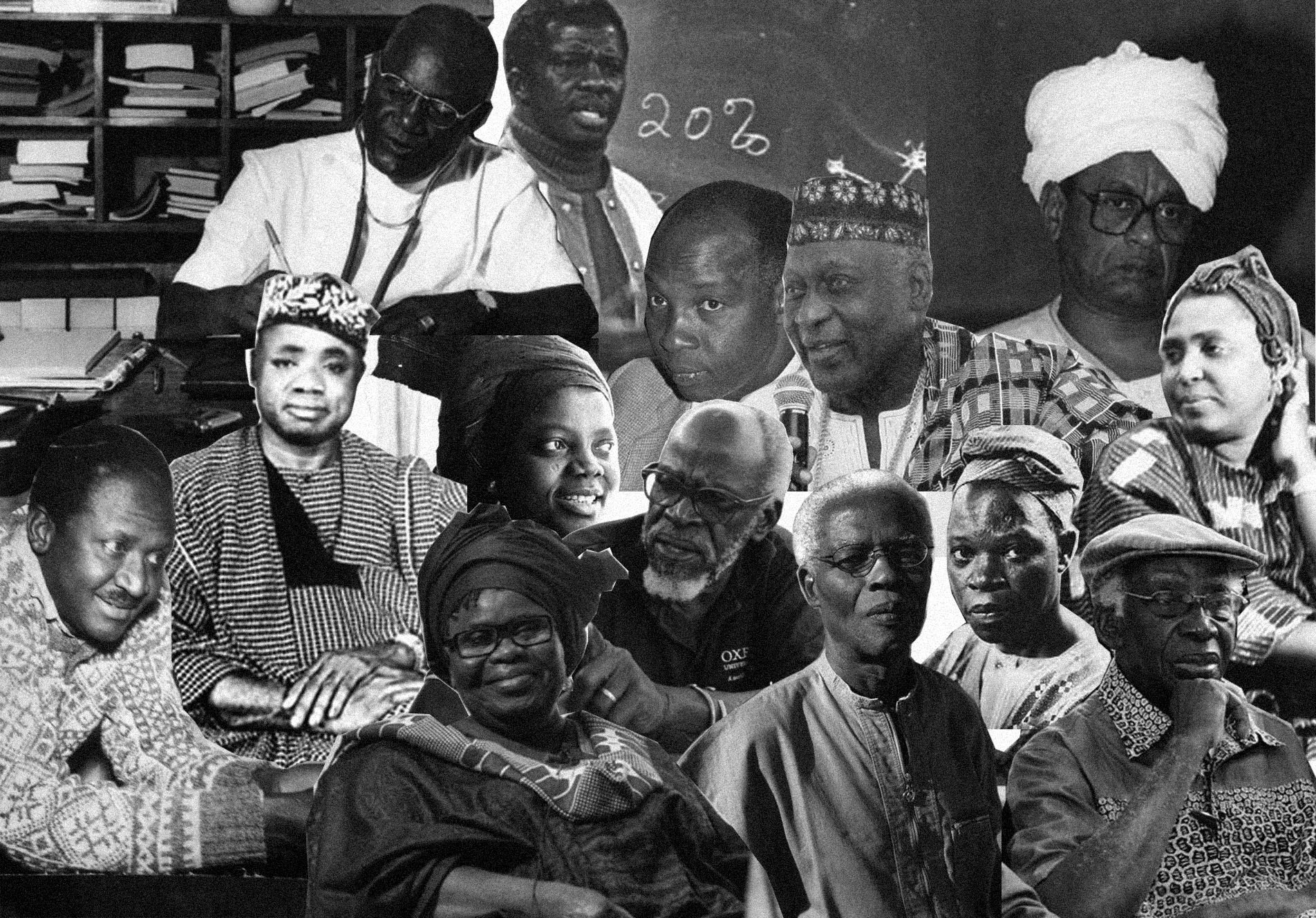

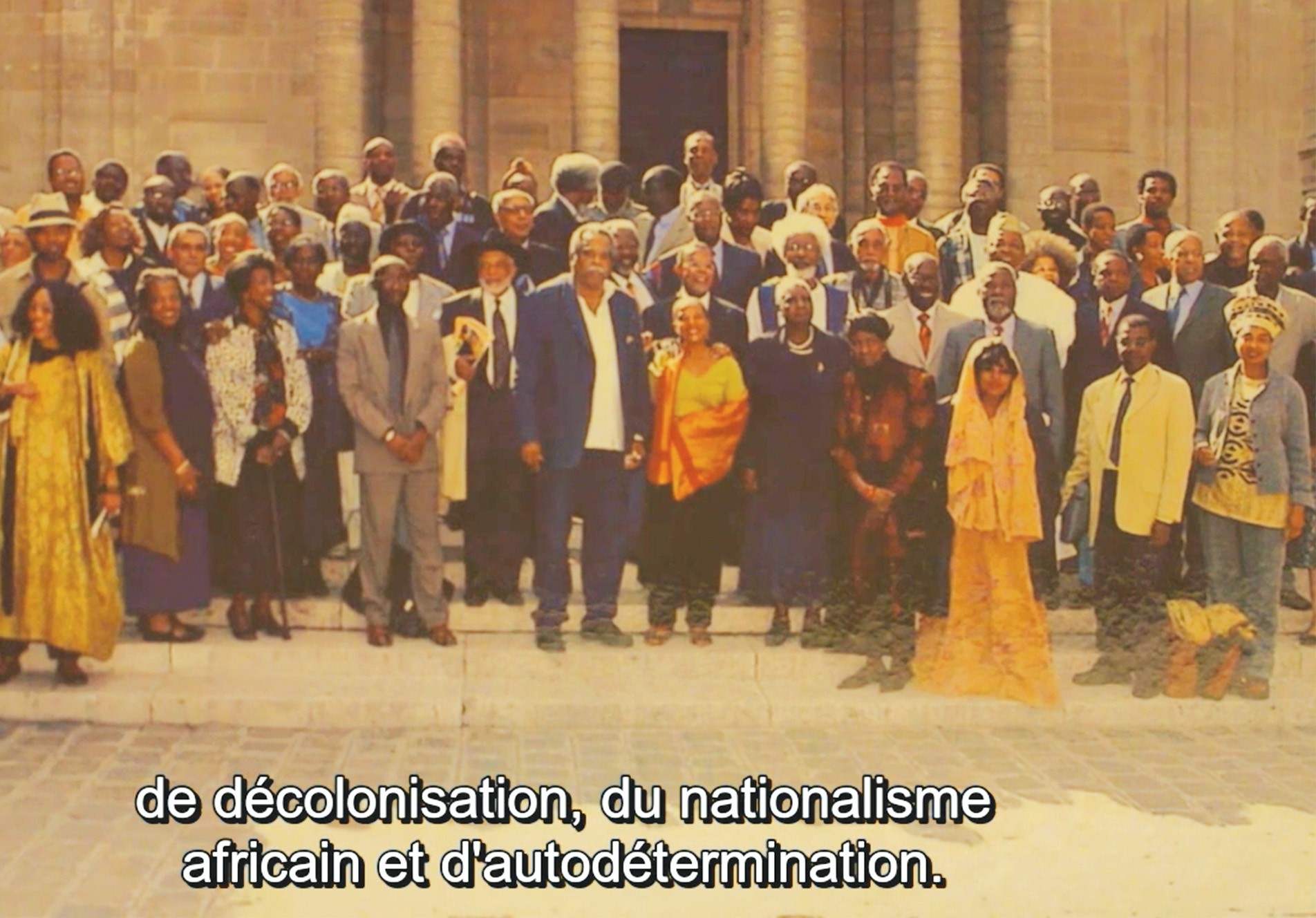

The accompanying books magazine, XiBARUU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

Inside Boubacar Boris Diop engages Cheikh Anta Diop’s legacy to raise radical views on creative writing, a challenge to what he laments as our literary Sahara. Similarly, Ayesha Attah travels from Diop through Ayi Kwei Armah to explore the ‘shared continuity’ of African cultures, histories and philosophies, while Ibrahima Wane presents Kàddu (“Speech” in Wolof), the first Senegalese newspaper printed entirely in an African language, as the missing link between Diop, Senegalese political scientist Pathé Diagne and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène.

The cover itself reworks the cover of the first issue of TAXAW, the journal founded by Cheikh Anta Diop in 1977 – officially, the mouthpiece of his party RND. Initially TAXAW was titled SIGGI, but the journal was censored by Leopold Senghor’s notorious grammar police – the spell-checking directorate Senghor set up to block radical

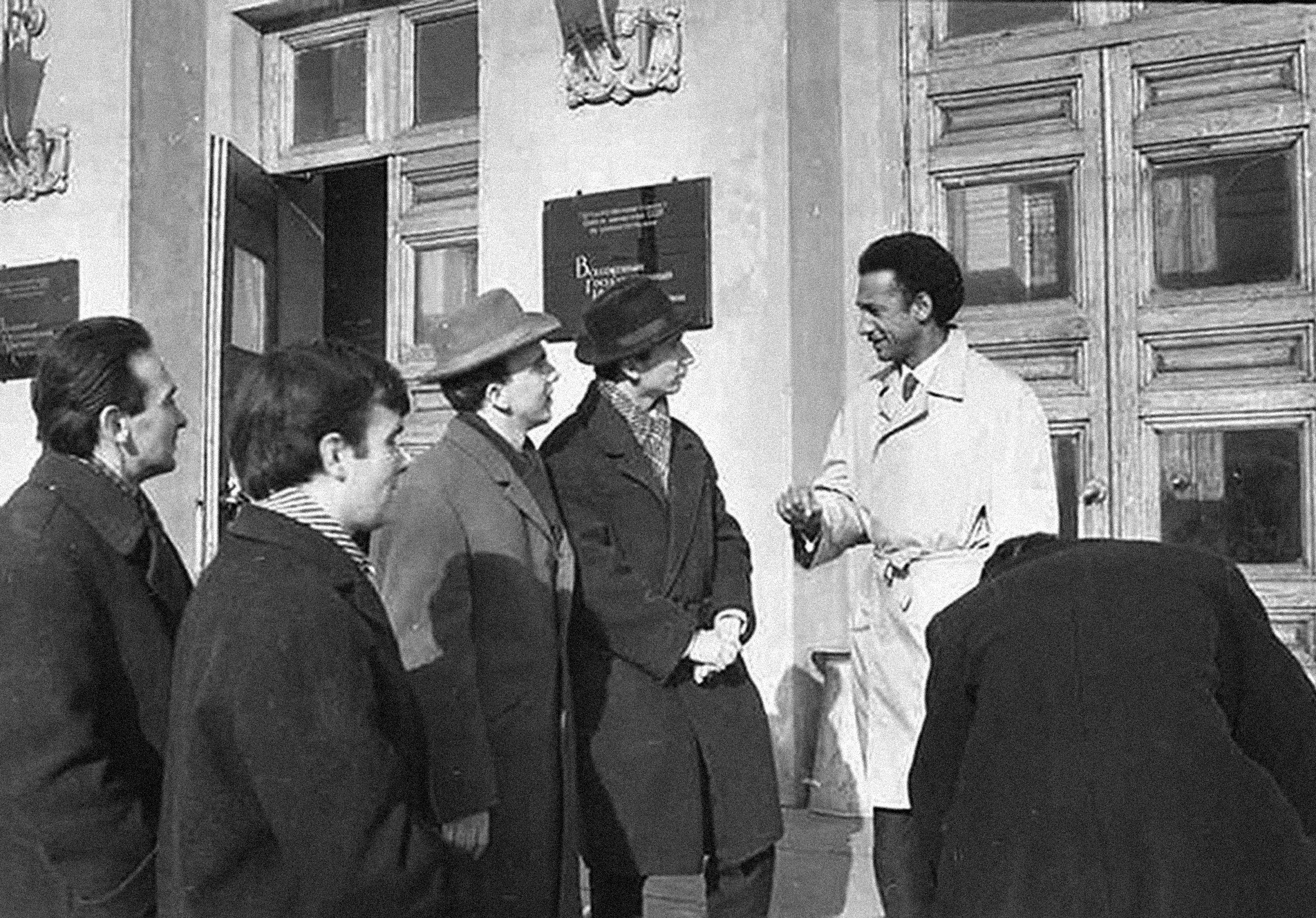

Mamadou Diallo channels exiled Cuban Carlos Moore, through his special relationship with Cheikh Anta Diop and their foremost, but failed collaboration to launch an organization of scientists of the black world are the focus of this extraordinary account.

Wolof publications on orthographic grounds! Cheikh Anta Diop responded by changing the name of the journal: “SIGGI (getting up) becomes TAXAW (standing), which is even more radical. We can thus sidestep the legal trap that they wanted to spring on us.”

Digging deeper into this radicalism, Souleymane Bachir Diagne enters Diop’s legendary Laboratory of Carbon 14 where he encounters the ‘demiurge’ for a new world view, a ‘new African’ conscious, embracing the genius of the ancestors in all domains of science, culture and religion.

Other accounts are offer by Khadim Ndiaye, himself a follower of the Murid way and author of a recent book on Cheikh Anta Diop, who shows how the late scientist, politician and thinker was a product of the Murid, and Sumesh Sharma who traces Diop’s legacy through the circuitous roots of Afro-Asiatic history, from the world’ first civilisations in Egypt to Dravidian civilisations of southern India.

XiBARUU TEERE YI also includes reviews and dispatches by Lindokuhle Nkosi, Gwen Ansell, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Kibafika Louis Kakudji, Akin Adesokan and many more.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop,or get copies from your nearest dealer.

No comments yet.