Shebeen as a school/ “Angazi, but I’m sure” April 3 – May 26 2017

“Angazi, but I’m sure” is a common South African phrase. In English it means: “I don’t know, but I am sure”. It is a deliberately self-contradictory phrase that is usually spoken in prelude to a reply – often, when one is asked for directions or facts. “Angazi, but I’m sure if you turn left you will get there”; “Angazi, but I’m sure they will start at 9pm”. The respondent is uncertain – of what they “know”. Or, perhaps, they are certain, but they do not know how to speak it. Or, they know, but do not know what they know. Sharing knowledge in this way requires mutual trust – it is speculation, in every sense of the word.

“Angazi, but I’m sure” is a break between our linguistic selves and a world, between knowledge and our ability to speak or map it – the knowledge that is elevated as finished product. The phrase suggests that arriving is as much about displacement as about place. More urgently, it affirms lived experience, improvisation and imagination as themselves forms of knowledge. It calls for a knowing through seeking and a constant transforming and renewing of our image of the world. Finally, it is an expression of community: “I know you will find the way”.

How do we learn to know what we know? How can we draw from disparate and often intersecting practices through which we stylise our conduct and daily life on the continent? How do we harness the inventiveness, the generative resilience and the agility with which we live?

This requires not only a new set of questions, but its own set of tools; new practices and methodologies that allow us to engage the lines of flight, of fragility, the precariousness, as well as joy and creativity and beauty that define the contemporary African moment.

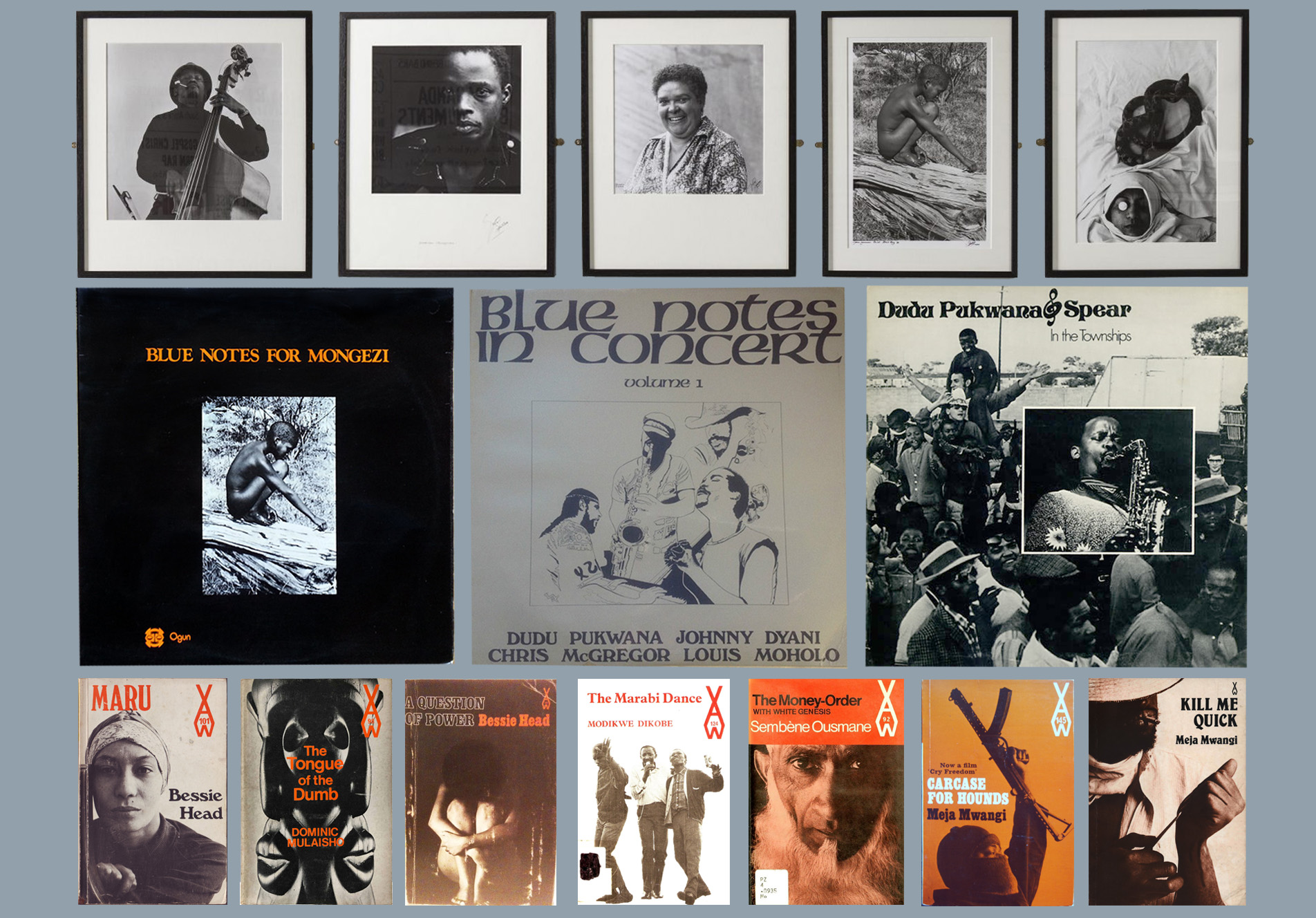

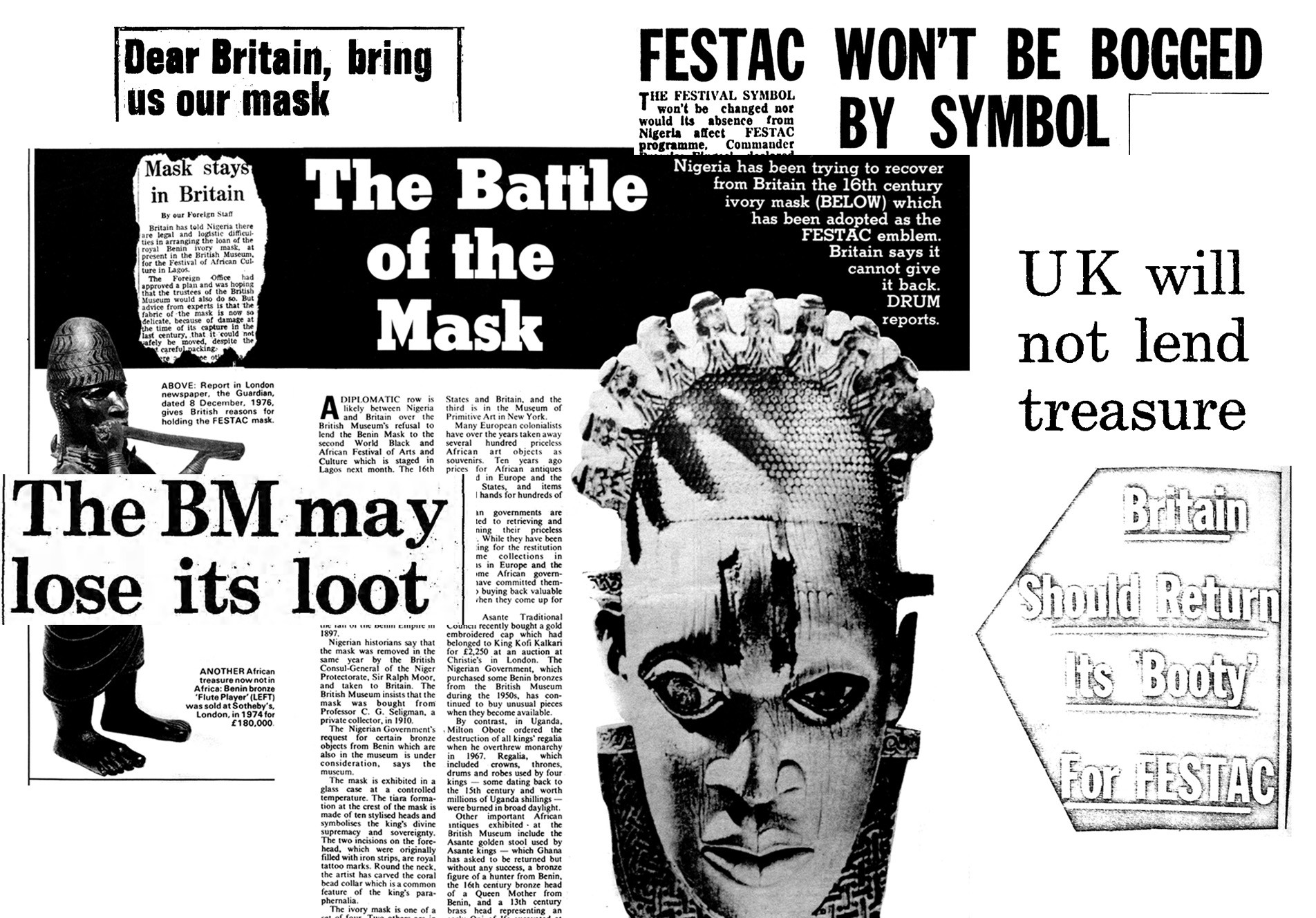

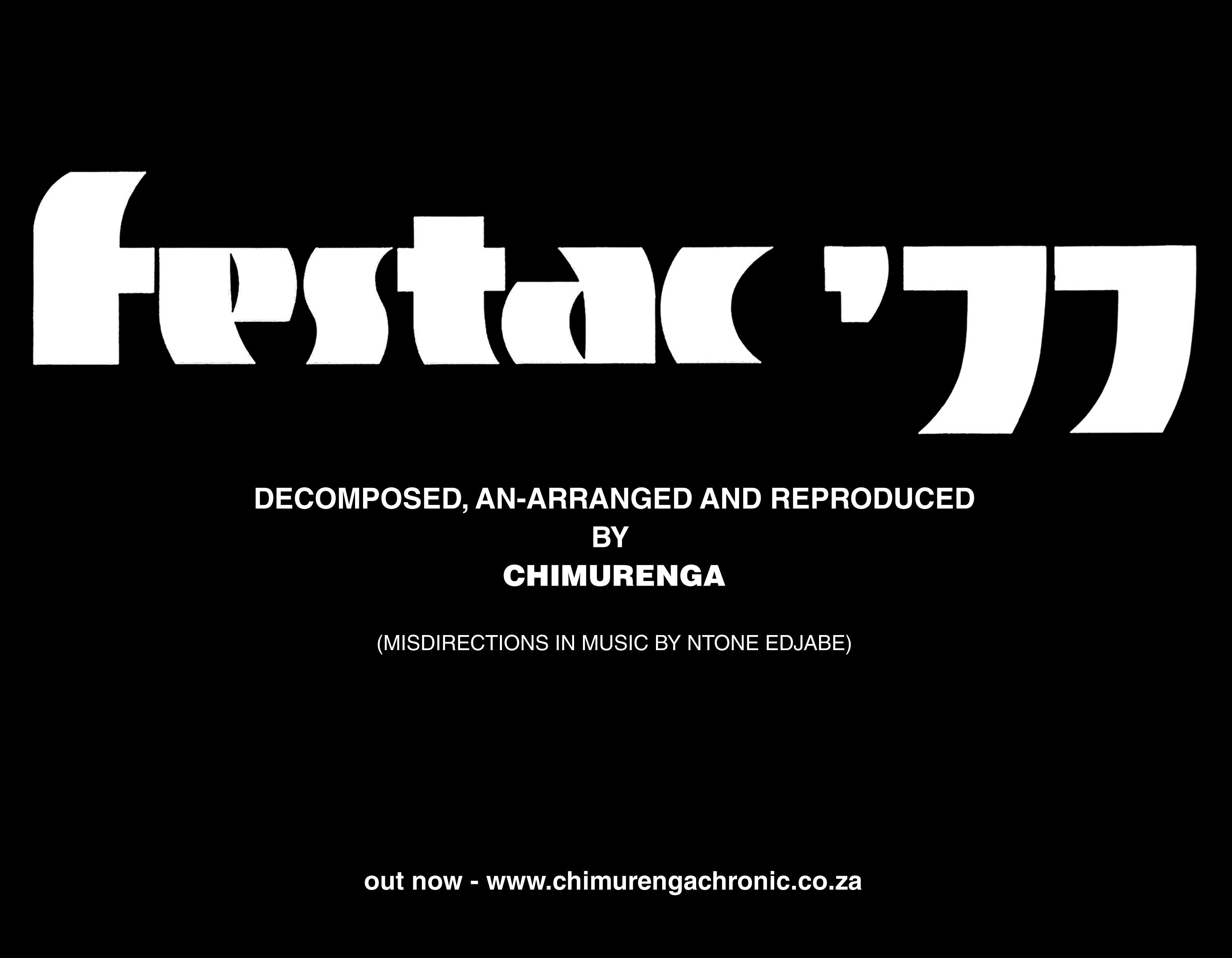

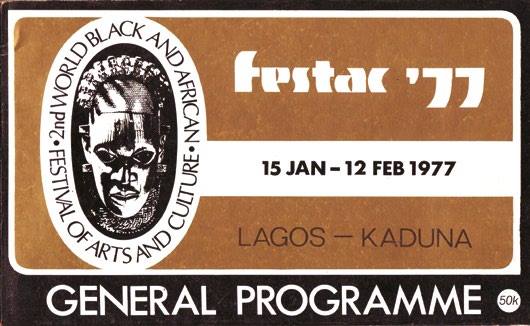

Chimurenga has long considered the shebeen (illegal drinking tavern) as a college of music. Can we draw on the improvisational, pedagogical method of black musics, where learning is collapsed into performing, and teachers and learners share the stage? How do we embrace knowledge not as information but as a methodology – a way of learning that expresses the conditions of our lives, our very existence. Can we take seriously food as knowledge, music as research and pan-Africanism as a practice? What if maps were made by Africans for their own use, to understand and make visible their own realities and imaginaries? What could the curriculum be – if it was designed by the people who dropped out of school so that they could breathe?

These are some of the queries this session will investigate, via the forms and media we use – such as cartography, comics, library-making, music, food, broadcasting and publishing, and in collaboration with Yemisi Aribisala, Neo Muyanga, Jean-Pierre Bekolo, Ibou Fall, Dominique Malaquais, Jihan el Tahri, Kodwo Eshun, Clapperton Mavhunga, Philippe Rekacewicz, Felwine Sarr, Lionel Manga, Victor Gama, Laila Soliman.

No comments yet.