In his seminal book, The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism, Brent Hayes Edwards traces the multiple encounters between black intellectuals from both the Anglophone and the Francophone world in Paris, during the early twentieth century, revealing how black studies emerged through such boundary crossing: “black radicalism is an internationalization.”

Edwards suggests that diaspora is less a historical condition than a set of practices: the claims, correspondences, and collaborations through which black intellectuals pursue a variety of international alliances. His book takes account of the highly divergent ways of imagining race beyond the barriers of nation and language. In the 1930s and 40s, the Paris metropolitan situation allowed contacts and collaborations that would have been unthinkable in the colonial world, so dominated by that dichotomy, so overwhelmed by the special relation to an imperial mère-patrie. As Edwards suggests, these many moves “across boundaries” (from colony to metropole, from one colonial system to another) were the real threat to colonialism, which is a discourse articulated first of all as singular and inescapable.

The fascinating convergences in Edwards’s account go well beyond the famous encounter of Negritude figures, Césaire, Damas and Senghor, with “Harlem Renaissance” poetry. He traces the wealth of black transnational print culture between the world wars, exploring the connections and exchanges among New York–based publications (such as Opportunity, The Negro World, and The Crisis) and newspapers in Paris (such as Les Continents, La Voix des Nègres, and L’Etudiant noir).

Thus, it is in the fragmentary, immediate, daily moments of the newspaper article and the periodical essay that we find the kinds of convergences and encounters that lay bare lost intellectual histories of black Atlantic traditions and pan-African movements.

However, following the institution of republican universalism during the 5th Republic, primarily a plot by the French state to retain its former colonies, the circulatory blackness that Edwards describes seems to fade from view – though black people never went away (on the contrary), France’s dark-skinned peoples were no longer black, but French citizens of African or Caribbean origin. This was enforced through a policy of “return” for African migrants following independence in the 60s, coupled with the notorious Bumidom, through which France imported cheap labour from its overseas “departments” in the Caribbean during the same period. In the institutions African and Caribbean studies would continue to enrich the colonial library but postcolonial and black studies would only be tolerated as exotic American imports.

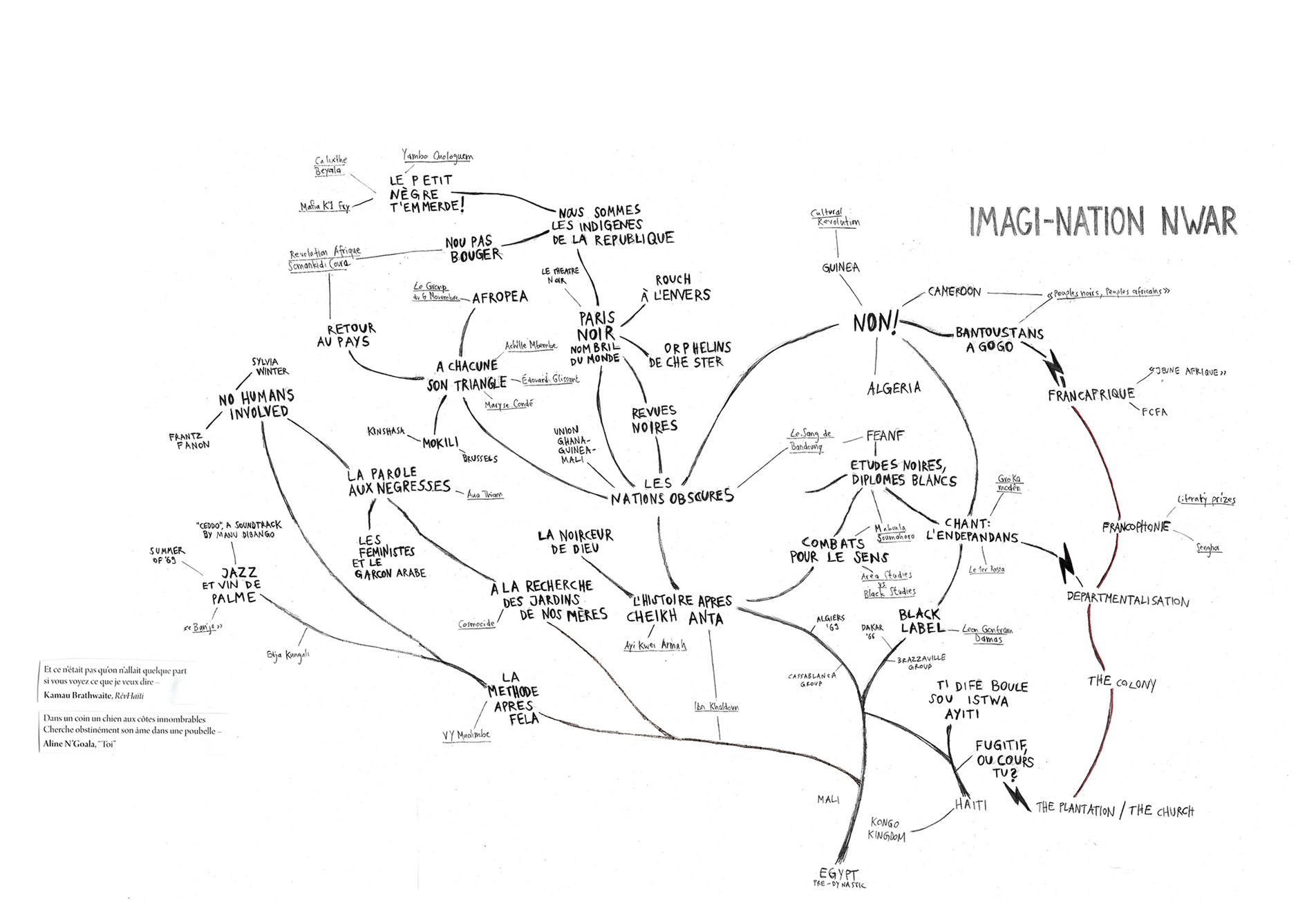

Using Edwards’ study as a starting point, and working on the ground in Paris, Chimurenga traced this history, from Negritude through the radicalism of the 1960s, and the independence movement across Africa and the Antilles that informed it, through the uprisings of 2005 across the French banlieues and contemporary social movements such as Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyion (Guadeloupe), Y’en a Marre (Senegal), Balai Citoyen (Burkina Faso) and more.

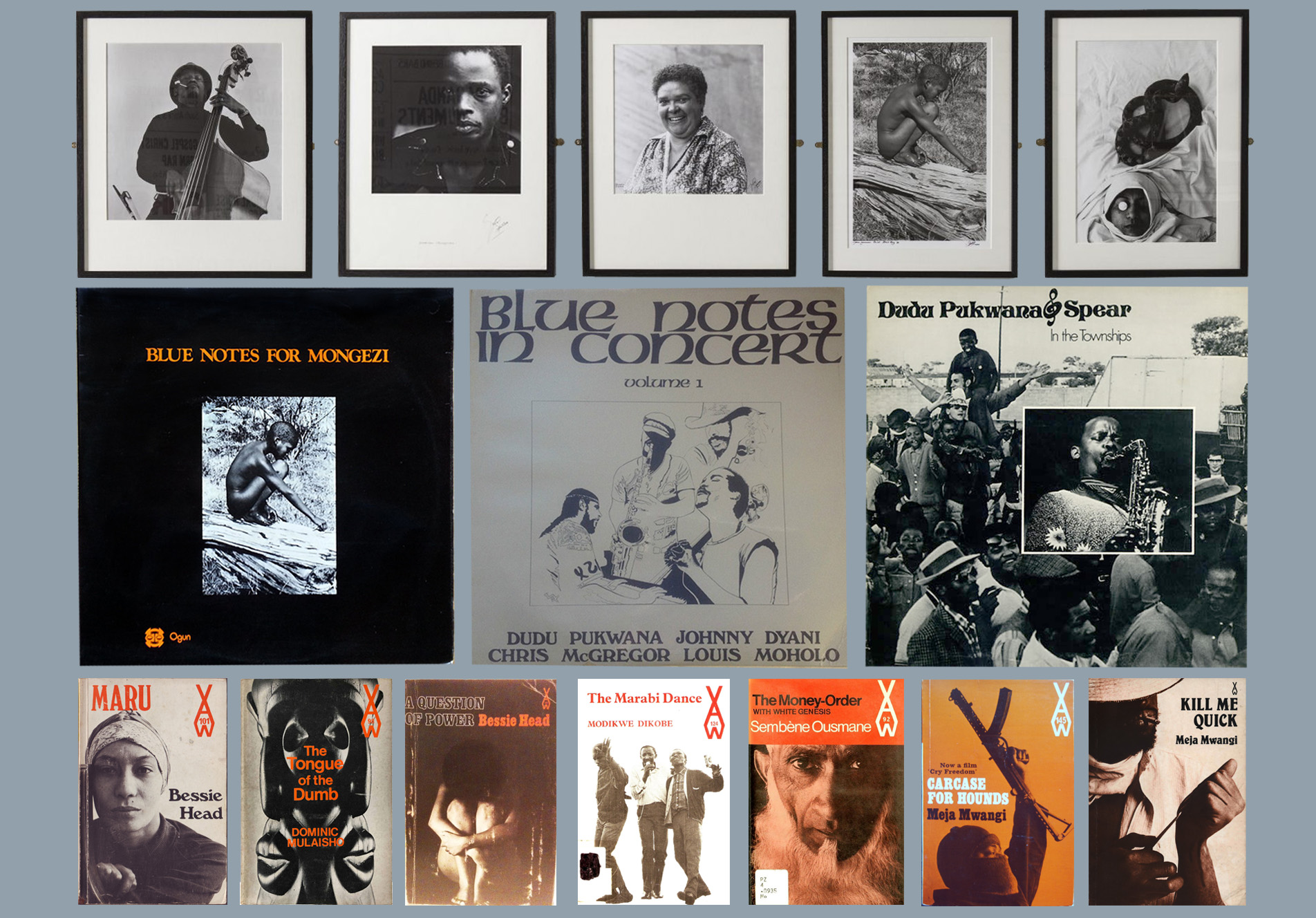

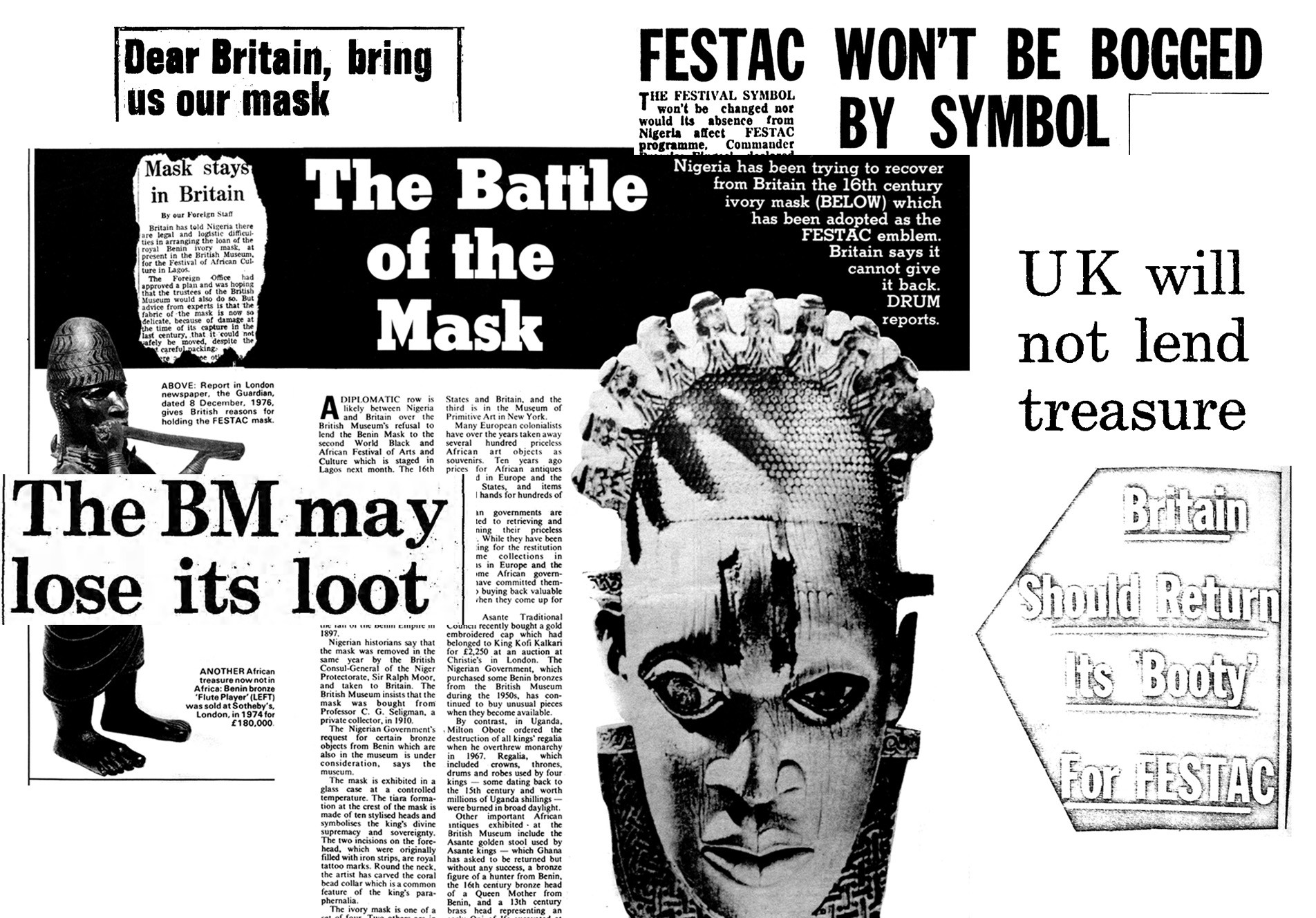

Our research engaged the black francophone archive, from works by key anti-colonial authors such as Césaire and Fanon, to numerous conferences (from the congresses of black writers and artists of 1956 and 1959, to the more recent “Bandung of the North” held in Paris); from early black feminist collectives such as La Coordination des Femmes Noires to contemporary groups like Cases Rebelles; journals of black expression from Mongo Beti’s Peuples Noirs, Peuples Africains and Edouard Glissant’s Acoma to Gesip Legitimus’s Black Hebdo; performance spaces such from Benjamin Jules-Rosette’s Theatre Noir to Alfred Panou’s La Clef; as well as texts on the black condition by authors such as Were Were Liking, Noel Ebony X, Awa Thiam, Leonora Miano, Yambo Ouologuem and more. As usual much of the research happened through music, particularly the output of the many collectives bringing together jazz musicians from Africa, the US and the Caribbean, in the years following the uprising of Mai 1968. We also explored the emergence of a black cinema in France.

To conduct this research, we worked collaboratively with Paris based thinkers, artists, musicians, activists, who through their work position blackness as a site of resistance, “a critique of western civilization” (Cedric Robinson), as well as an affirmation of the possibility and indeed existence of other worldliness, and an expression of community.

We drew on the multiple expressions of the black radical tradition as it continues to fluctuate and circulate in both the large body of knowledge that has long existed in the French-speaking world, albeit without institutional recognition, and in the lived expression of everyday blackness as it is performed and spoken today.

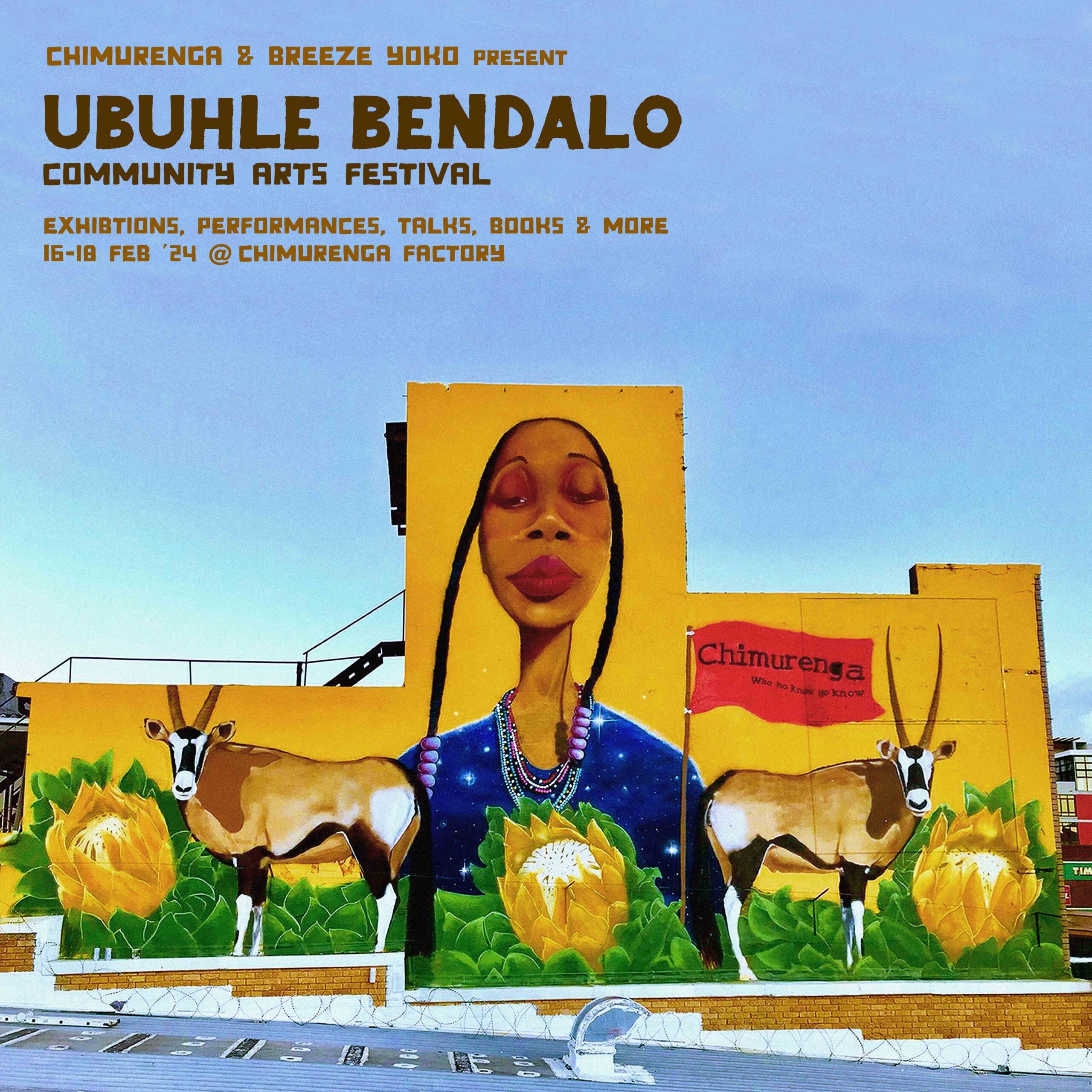

The Bibliotheque Chimurenga took the form of a two-year research in the collections of the Bpi and Kandinsky libraries, as well as key archives such as BnF and smaller, municipal libraries such as Saint-Denis; La Goute d’Or, Francoise Sagan, and more importantly, in the personal collections of the protagonists listed above. The research culminated in a library installation in the Bpi, along with a pop-up studio of the Pan African Space Station at Lavoir Moderne Parisien in Goute d’Or.

The installation not only pointed to the absences on the shelves of the Bpi and other organs of Centre Pompidou, but rather to make visible what is in fact there, or should be, through contrapuntal readings and a putting-in-relation of the material displayed in the public libraries with the knowledge embodied by the people who visit those libraries. While PASS, through its programming, further explored the notion of people as knowledge. A special French edition of the Chronic, titled “imagi-nation nwar” published the research and served as installation catalogue.

No comments yet.