In an essay titled “Roforofo Fight,” oppositional politics expert Yomi Durotoye describes legendary musician and activist Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s life as an “epic, contra-diction-riven roforofo fight against postcolonial domination.” The quote references Fela’s 1972 song, “Roforofo Fight”, in which the Afrobeat King describes a battle from which no participant emerges unsullied; a mud-slinging contest. For Fela, roforofo was a potent metaphor that captured the urgent need to construct radical counter strategies to resist colonialism’s ongoing domination. As Fela explained, “Because we are dealing with corrupt people we have to be rascally with them.”

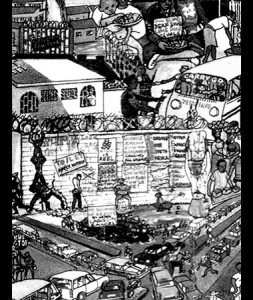

Throughout his life, Fela’s rascality was acted out at different sites and with different weapons: stage, home, street, studio. One of his typically “rascally” moves was to turn the tools of corporate capitalism and colonialism against their masters. Bypassing editorial censorship in Nigeria’s predominantly state controlled press, Fela thus began buying advertising space in daily and weekly newspapers such as The Daily Times and The Punch in order to run outspoken political columns. Published throughout the 1970s and early 1980s under the title, Chief Priest Say, these columns were essentially extensions of Fela’s famous “Yabi Sessions”, consciousness-raising word-sound rituals, with himself as “chief priest”, conducted at his Lagos nightclub, the African Shrine. Organised around a militarily Afrocentric rendering of history and the essence of black beauty, Chief Priest Say focused on the role of cultural hegemony in the continuing subjugation of Africans. Employing genre malleability, a trickster’s penchant for play and language games, withering social satire, incantations and invocations, Fela’s writing constituted a literary symphony of dissent and resistance. From explosive denunciations of the Nigerian Government’s “criminal behaviour”, Islam and Christianity’s “exploitive” nature and the and “evil” multinationals, to witty deconstructions of Western medicine, Black Muslims, sex, pollution and poverty – nothing was safe from Fela’s phallacious pen.

Chief Priest Say was finally cancelled, first by Daily Times, then by Punch, ostensibly due to non-payment, but as many commentators speculated more likely because the paper’s respective editors were placed under increasingly violent pressure by the government who were determined to silence Fela.

“The uniqueness of Fela as a political artist, Olaniyan argues in a stimulating analysis, lies, all told, in his role as a pedagogue. He not only uses his songs as teaching tools, he is also concerned, and even more pointedly, that the point of his teaching is understood in its entirety. It is the coda of the storyteller or the folkloric moraliser, except that, like the structure of the long-song, the code is broken before the ruse is enacted.”

METHOD AFTER FELA by Akin Adesokan

traduction française par Scarlett Antonio

Dans un essai intitulé “Roforofo Fight” (le combat de Roforofo), l’expert en politique oppositionnelle, Yomi Durotoye décrit la vie de Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, un activiste et musicien légendaire, comme un “combat roforofo, épique et fendu par la contradiction contre la domination postcoloniale.” La citation se réfère à la chanson de Fela 1972, “Roforofo Fight”, dans laquelle le roi du rythme afro décrit une bataille à partir de laquelle aucun participant ne sort sans souillure; un tournoi de médisance. Pour Fela, Roforofo était une métaphore puissante qui captura le besoin urgent pour construire des stratégies contraires et radicales afin de résister à la domination continue de colonialisme. Comme l’expliquait Fela, Parce que nous traitons avec des gens corrompus, nous devons être retors avec eux.”

Tout le long de sa vie, la ruse de Fela était jouée à différents endroits et avec différentes armes: la scène, la maison, la rue, le studio. Une de ses mouvements typiquement “rusé” était de tourner les outils du colonialisme et capitalisme contre leurs maîtres. Détournant l’interdiction de rédaction au Nigéria, état avec une presse contrôlée d’une manière prédominante, Fela commença ainsi à acheter des espaces publicitaires dans les journaux quotidiens et hebdomadaires tels que The daily Times et The Punch afin de publier des colonnes politiquement engagées. Editées dans les années 1970 et au début des années 1980 sous le titre, Chief Priest Say, ces colonnes étaient essentiellement des extensions des fameuses “Sessions Yabi” de Fel, rituels conscience-élévation mot-son, avec lui-même comme “prêtre chef”, conduits dans sa discothèque au Lagos, le Lieu saint Africain. Organisé autour d’une interprétation militairement Afro-centrée de l’histoire et l’essence de la beauté noire, Chief Priest Say mettait l’accent sur le rôle de l’hégémonie culturelle dans l’assujettissement continu des africains. Employant un genre de malléabilité, un penchant filou pour les jeux de scène et de langage, détruisant petit à petit la satire sociale, incantations et invocations, les écrits de Fela constituèrent une symphonie littéraire de dissentiment et de résistance. Des dénonciations explosives du “comportement criminel” du gouvernement Nigérien, la nature “exploiteuse” de l’Islam et du Christianisme et les multinationales “néfastes”, aux destructions spirituelles de la médecine occidentale, des noirs islamiques, du sexe, de la pollution et de la pauvreté rien n’était sauvegardé du stylo fallacieux de Fela.

Chief Priest Say a finalement été annulé, en premier par Daily Times, puis par Punch, ostensiblement en raison de non-paiement mais comme de nombreux commentateurs l’ont spéculé plus vraisemblablement parce que les rédacteurs respectifs du journal étaient placés sous la pression de plus en plus violente par le gouvernement qui était déterminé à mettre Fela sous silence.

PEOPLE

- Fela Anikulapo-Kuti

- Artist and political activist Ghariokwu Lemi, who designed many of Fela’s album covers, also designed several “Chief Priest Say,” columns in the mid-1970s.

RE/SOURCES

- Durotoye, Yomi. “Roforofo Fight”, Fela: From West Africa to West Broadway, Schoonmaker, Trevor (ed.), Jacana Media, 2003

- Veal, Michael E. Fela: The Life & Times of an African Musical Icon, Temple University Press, 2000.

- Olaniyan, Tejumola. Arrest the Music!: Fela and His Rebel Art and Politics, Indiana University Press, 2004

- Kuti, Fela. Roforofo Fight, Jofabro / Editions Makossa / Pathe Marconi, 1972.

- Chimurenga Volume 8: We’re all Nigerian!, Dec 2005.

- Idowu, Mabinuori Kayode. Fela: Why Blackman Carry Shit, Opinion Media, 1986.

- Olorunyomi, Sola. Afrobeat!: Fela and the Imagined Continent

- Edjabe, Ntone. “Why Blackman dey carry shit”, Chimurenga Vol 1: Music is the Weapon, April 2002

No comments yet.