“Why did we embark on this insane trip?” Having journeyed together from Douala to Dakar, Goddy Leye, LucFosther Diop, Justine Gaga, Dunja Herzog, Achillekà Komguen and Alioum Moussa* report on the questions, lessons, and collaborations of the inaugural Exitour.

It all began when a group of young, talented artists were selected and invited for a one-month stay at the ArtBakery in Bonendale, Doula, an incubator for alternative reflection and production by emergent creators in the fields of visual, video, installation and performance art. Among the pioneers that year, 2003, were LucFosther Diop and Ginette Daleu. The main aim was to provide these artists with the tools to prepare them for a smooth introduction into the art arena through extensive exchange, collaboration and discussions with more experienced artists living in the vicinity, and those who would be invited to the ArtBakery from elsewhere.

This led to a year-long process, during which paths of research were explored and deepened, providing the artists with a better knowledge of each other’s interests, as well as a bird’s-eye view of the local art scene. It also provoked a thirst for greater knowledge of the art system in countries sharing similar socio-economic environments.

From this emerged Exitour 2006, a voyage that brought seven artists to travel, by foot and by bus, from Douala to Dakar – more specifically the Dakar Biennale, where they could meet some of the most important personalities in the realm of contemporary African arts. They would, thereafter, return to Douala to digest the impact of their international tour.

The group had several questions in mind at the outset: Who are the leading protagonists of contemporary art in the countries that we will cross? What is the official cultural policy of each country? What kinds of strategies do artists develop there? What prospects for collaboration and exchange exist, with both individuals and institutions?

The trip was rich, and complicated, and the story extraordinary.

Goddy Leye (2009)

We left on 27 March 2006. It was a Monday. Our first stop was Calabar. No easy trek. From Douala, we headed southwest to Limbe. The ferry we found there was near to keeling over from overload, so we chose instead to go by chaloupe – a hand-made resin dinghy with a tiny outboard motor and just enough room for nine passengers. On the high seas, we ran into no fewer than ten checkpoints. At each, the same rite of passage: hand over the Naira. Hardly a surprise for us – we’re from Cameroon after all and our police are world champions in the ‘hand-it-over’ department – but still…

All of us, throughout the trip, were struck by the violence that occurs at borders in this region we call home. Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Burkina, Mali: demands for money, searches, theft of goods and material. And then Senegal, where they just wouldn’t let us in; where we waited five days, stranded at the border.

No doubt, part of the problem was that we did not have our own car or bus. Public transportation (or what passes for such) all the way: combis, motorbike taxis and the occasional hitch-hike ride – that was how we went. There were two reasons for this. The first was financial. Although some of us had funding for travel from Art Moves Africa, and one of us a grant from a European institution, two had no support whatsoever. In the end, we all pitched in from our savings, but the pot was small. Very small. The second reason was a determination to experience this place called West Africa as so many people see and live it daily: the simple, hard way.

No doubt, part of the problem was that we did not have our own car or bus. Public transportation (or what passes for such) all the way: combis, motorbike taxis and the occasional hitch-hike ride – that was how we went. There were two reasons for this. The first was financial. Although some of us had funding for travel from Art Moves Africa, and one of us a grant from a European institution, two had no support whatsoever. In the end, we all pitched in from our savings, but the pot was small. Very small. The second reason was a determination to experience this place called West Africa as so many people see and live it daily: the simple, hard way.

The economics of the tour made for haphazard housing: hostels, mostly of the low-rent variety; sometimes the home of a friend or a generous stranger met along the way; an empty theatre, once; outdoors, between parked trucks, one of us standing guard over our precious laptops and cameras.

We documented everything. Goddy Leye had a website going, which he updated daily with our pictures, drawings and words. Sadly, now, the link has gone dead. But the networks built during the tour have not. Several of us remain in contact with people we met – visual, installation and performance artists, filmmakers, curators, professors of art, poets and playwrights: Akirash (Nigeria/Ghana), Kofi Dawson (Ghana), Benjamin Deguenon (Benin), Hama Goro (Mali), Eza Komla (Togo), Abdoulaye Konaté (Mali), Rafiy Smith Okefolahan (Benin), Kofi Setordji (Ghana), Abdou Sidibé (Burkina), Dominique Zinkpè (Benin), to name just a few. With some, we continue to collaborate: Rafiy and Eza, for instance, recently took part in a month-long video workshop at the Bakery.

Each day began with a lively discussion, covering practical matters (how to get the next visa, where to live) and, more importantly, what and whom we wanted to see, and how we felt about a previous visit, about the art, the artists and the artists’ networks we were encountering. Everywhere, we sought to meet as many art-world actors as we could. Wherever possible, we held workshops with our new acquaintances and, in several cases, this gave rise to exhibitions and performances. In Cotonou, for instance, we organised several roundtables and a group show with Beninois artists in the lounge and the garden of a hostel we were staying at. In Lomé, we staged a performance and an exhibition of our own work. In Bamako, we met up with our countrymen, Bili Bidjoka and Simon Njami, who invited us to take part in a show Njami was curating.

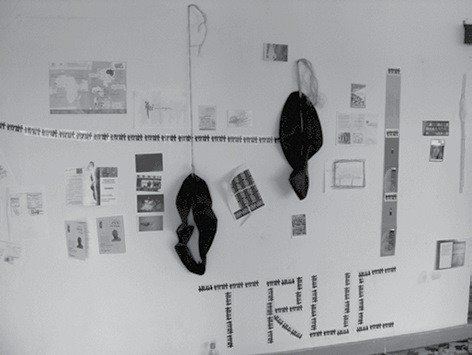

Along the way, we made many things: countless pictures, videos, paintings, drawings, installations, performances. One creation was “The Enterprise”. The fundamental idea was to communicate with as many people as possible about our project. So we created a logo that also displayed the link to our homepage. This we first printed on stickers, which we handed out and pasted everywhere we went. Then we printed the logo onto sheets of paper. These we used to create in-the-city installations, plastering vast swaths of wall with the sign of our passage. Mostly, this was done surreptitiously, under cover of darkness. Once, in Bamako, we were invited to create such a wall installation as part of an exhibit. Next, we printed the logo on T-shirts and bags, for sale on the way to and at the Dakar Biennale. Sales helped cover our expenses – a key point for us, as we wanted the tour to be self-sustaining, rather than supported by Western organisations. Part-art, partadvertisement, part-communication device and self-funding venture, “The Enterprise” was a conceptual work, devised to function on multiple levels in different places and at different times.

In the end, most of us missed the better part of the Dakar Biennale. Only one of us, the member of the group from the west, was allowed to cross the border into Senegal. The others were refused entry, on the grounds that Cameroonians making their way north could only be up to no

good. Broke, we camped out at the border, waiting as message after message sent from Dakar spoke to our good intentions. In the end we got through, but too late to take part in the many events that had been planned for us in Dakar.

Why did we embark on this insane trip? In a thirst for knowledge: because we had to know what and where and how art was happening outside Cameroon, the only place most of us had known. How did we make it? Through sheer will, curiosity and folly too, but also because of Goddy: his

conviction, his kindness, his utter generosity. Moreover, when you embark on a trip of this kind, a self-sustaining energy builds up, pushing you onward. For all of these reasons, we went and kept going. Would we do it again? Some of us say undoubtedly yes, others no – not under such

harsh conditions. But all of us – to a person – agree: Exitour radically changed our views of the world and the ways we make art.

*Translated by Dominique Malaquais

This report features in the August 2013 edition of the Chronic, as part of “Overcoming Maps”, an exploration of artists’ projects centred on pan African travels and encounters. Available in print or as a PDF.

The issue also features reportage, creative non-fiction, autobiography, satire, analysis, photography and illustration to offer a richly textured engagement with everyday life. In its pages artists and writers from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/product/the-chronic-august-2013-2″ color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button]