By Stacy Hardy

My cover is easy. There are a million roles I can assume. A thousand identities to choose from. But they are all the same. Worker. Foreigner. Non-resident. Non-citizens. Visa. People. A Million. More. Homeless. Visiting. Residing. Born. Brought. Arrived. Acclimatizing. Homesick. Lovelorn. Giddy. Tailor. Solderer. Chauffeur. Maid. Oil-Man. Nurse. Typist. Shopkeeper. Truck Driver. Watchman. Gardener. Temporary people, as Deepak Unnikrishnan calls them. Smuggler. Hooker. Tea Boy. Mistress. Temporary. Illegal. Ephemeral. People. Gone. Deported. Left. More. Arriving.

It will be easy for me. Like me, they are wanderers, although for very different reasons; nobody drove me out of my country, I have never travelled. My name is Paolo Bruno. I have a white father and a black mother. I am both African and European. For blacks, I am white. For whites, I am always a black man. You can call me Ibrahim or Saba, Matteo, Adama, Francesco, Ebongué, Claude or any other name you chose. Maybe I am merely a made-up person, an alter ego invented for my story. Or my name is really Samir or Paulo Diop Ravenna and I am a character hijacked straight from the pages of a migrant writer like Pap Khouma or Tahar Lamri to serve a purpose.

Already my words are over familiar to you. My name is Suleymane, Aymen, Tommaso, Nikita, Simon, Modou, Shukri, Taageere, Xirsi, Diriiye, Safiya, Barni. You see me with my friends on the streets. We talk in loud Italian. Every now and again we stop for a kebab or a pizza. These are our borders, the germinal points of arrival in our daily comings and goings in and out of the house. We could name ourselves a thousand other ways and be the protagonists of a thousand stories, most hard like a punch to the stomach, a few have happy endings. What’s important is that in everyday life as in fiction there exist many true Paolos.

We are the new citizens of Italy. Labeled as second-generation immigrants. It was not us who travelled. We followed in the wake of our parents’ journey and found ourselves here. Immobile travellers, eternally travelling. I know just one urban landscape and it is this one here before my eyes, or rather, here inside me, in the depths of myself. The label I bear—second rate citizen, second generation—carries within it a journey not made by me, a stigma inherited rather than earned. I have a movement without ever having gone anywhere.

Like me, my employer does not divulge his real name. I do know know who he is exactly. It doesn’t matter. I can call him Luigi or Matteo or Luca or Pietro or Roberto or Maurizio or Simone. It makes no difference. I imagine he is mafiosi. Or from the far right—one of a plethora of small parties and movements with extremist ideologies that has sprung up lately. Their names are in the papers and on TV—the National Front in Italy, CasaPound Italy, Lega Salvini Premier, Forza Nuova allied with Fiamma Tricolore to form the Italia agli Italiani far-right coalition.

I encountered many of their supporters during my years in prison. They were not unlike to me and my friends. They too are from working class families. They too have never travelled. Like me, they know nothing. They are home here but they live on the margins of society. Like me, they work various jobs. Look for work. Look and despair. Because the living is easy in Europe, as everyone knows or presumes or imagines, but only if you have some money or a scholarship or a wealthy family or even a measly casual job working in agriculture, or as petty drug pushers, pimps, or prostitutes in piazzas and urban train stations. But even these jobs are scarce these days. Like me, they live with their mothers; their bellies are full but they are hungry. It is the same for all of us. We spend our days on the streets or in bars, smoking and talking, complaining and scheming, dreaming of a future that never comes.

I met my employer at one such haunt in Ballarò. An ironic destination? No, I doubt my patron has the flare or imagination for that. Rather, I guessed, that it provided him with a handy cover for the transaction, but also spared him being seen in public with someone like me: a black man, black Italian. If the setting, with its loud music and smells of maffè, bothered him he gave no indication. We took a table near the back and got straight to business. He said he had heard of my work, that’s what he said.

It’s been a while since I worked, I retorted.

It’s better this way, he replied then, without missing a beat, he placed a leather briefcase on the table and begun to open the lock. It was then that I saw the envelope. He handed it discreetly to me across the table.

I haven’t said yes, I said as I slipped my finger inside and touched the notes. It’s been a while, I insisted.

I remember how warm the wind was that day. It was blowing in from the sea and I remember the salt. The taste of salt in the air. I remember what I wanted to tell him, as we sat across from each other in that bustling café whose windows were grazed by the ocean salt, that clingy, inescapable substance that reminds us all who we are—or how we got here—when we feel it on our skin or tongue. Instead of taking the money from his hand and nodding in agreement, I wanted to say: in the end, we are similar, him and me. You and I. You me. The Syrians and Sri Lankans and the Senegalese, the Arabs and Indians and the Chinese, and the Roma, the soccer hooligans of Juventus or Lazio, Po Valley politicians, the migrants and the killers of Yusapha Susso… We are all of us one human race.

Instead I bit my tongue. I counted the notes. I took the job for the same reasons one always takes these jobs. The thickness of the wad in front of me. The freedom it promised. The freedom to escape my birth, my history and destiny. You can call me a sellout. Fine, I am a sellout. Is it not economic that governs life? I take comfort in the words of Khouma’s Elephant Salesman, who, like me is a second generation migrant: selling is not only a question of resistance… it is an art.

Maybe killing is one too? At any rate, the job was easy for me. It is true I know nothing of the world. It is true I have spent much of my life in prison, behind bars, but I used my time well. For my cell I made a thousand journeys. Safir fa fi assafaru sabaatu fauaid—Journey forth, because travel has seven benefits—one of the Arabs in my cell block told me when I first arrived. I challenged him to name one. He smiled, then explained that the word “safar,” has the same root as “book”—“sifr.” Every journey is a reading. Every book is a journey.

As if to demonstrate he began to loan me things from his library. From him I read the greats of Italian literature: Dante Alighieri, Carlo Levi, Italo Calvino, Alessandro Manzoni, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa. From this same library I have I also learned the language of parents. The migrants tongue. A tongue that usually is cut out. Silenced. But these days literature is overflowing with stories of migrants. I have as my guides Senegal-born Pap Khouma and Saidou Moussa Ba, Moroccan-born Mohammed Bouchane, and Tunisian-born Salah Methnani. I have Ubax Cristina Ali Farah and Igiaba Scego of Somali origin; Shirin Ramzanali Fazel and Sirad S. Hassan, also from Somalia, Maria Abbebù Viarengo and Gabriella Ghermandi from Ethiopia, Erminia Dell’Oro and Ribka Sibhatu from Eritrea, then there is the Cameroonian-born Ndjock Ngana, and from beyond Italy there is Nadifa Mohamed, Fatou Diome, Laila Lalami, Shailja Patel, Alain Mabanckou, Abdurahman Waberi, Tahar Ben Jelloun, Paulette Nardal, Warsan Shire and more: Deepak Unnikrishnan, Dinaw Mengestu, Sulaiman Addonia, Nuruddin Farah, Biyi Bandele, Leila Aboulela, Jamal Mahjoub, Moses Isegawa. This is to say nothing of the whole generation of migrant Nigerian writers birthed by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. As Equatoguinean writer, Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel puts it: the story of a continent emptying itself in order to go to another one has to be told.

From these, I am easily able to construct a cover story that will gain me direct access to my target. He is himself a character out of a novel or a movie. A legend in Italy for taking on Palermo’s mafiosi, today he claims he is fighting for migrants to freely enter EU states. He is also himself an author. From his book, Fighting the Mafia & Renewing Sicilian Culture, I can gain access to his long war to end the Mafia’s decades-long reign, the struggle that came after to preserve what he calls the civic life of a great European metropolis that followed. I read between laughing. I consult other sources. The mayor’s habits are well documented by the press. He is a regular on the streets of Palermo, I see him myself. I have witness his pageant on the docks. His pantomime of shaking the hands with those newly landed. Every time a ship with rescued migrants enters the harbour of Palermo, the mayor is there to greet them. Welcome, he says again and again. Welcome. Welcome. The worst is over. You are citizens of Palermo now.

Like my fellow travellers, I will be there to shake his hand. I will have no trouble gaining access. I can adopt one of a hundred stories. I will speak of my reasons for making the journey. There are so many motives to travel. So many routes to take, but only one destination. I will tell a heart-wrenching story. I will say war drove me. I will quote Ali Farah and describe the violence that erupted suddenly. I will pepper my language with strong images: A burning city that glows like a brazier. A filthy firework under the full moon. They ask me how did you get here? I will answer: Can’t you see it on my body? The Libyan desert red with immigrant bodies, the Gulf of Aden bloated, the city of Rome with no jacket (Shire).

Or maybe I will take a more measured intellectual tone like that of Nuruddin Farah or Mahjoub. Speak of economic hardship. I will conjure history and point to the legacy of violence in Africa, an epic tale of clashing creeds, of colonialism campaigns and conquests. I will point to the hopelessness of my future. I will say: All those legions of third-world areas coloured red on the map, soon decimated… Devaluation. Demolition of our currency, of our future—of our lives, pure and simple! On the scales of globalisation, the head of a third-world child weighs less than a hamburger (Scego).

Or I can evoke Binyavanga Wainaina, claim it is a rite of passage. A contemporary coming of age ritual to be performed by all young men. Why is it only westerners are allowed the luxury of travel and time to find themselves? Maybe I will say there is nothing to be found. I will simple say madness overcame me. I will call it a pandemic that spread like the plague…. The bell rang and rang, sparing no one, infecting minds with the migration bug (Kahal).

Maybe I will tell all these stories one after the other. As Ávila Laurel says it: Don’t ask me where I came from. It was via lots of places… They told me I no longer have a country, that’s what they said at the border: you’ve no country any more, now you’re just black.

Or I will tell none. I will say nothing. Simply stand and stare. Tight-lipped. Mute. After all as I have learnt from Souleymane Bachir Diagne: When you know long before you get there that the Europeans will want to deport you on arrival, it is imperative you do all you can to flummox them…. Say nothing at all and there is nothing to translate.

When the mayor comes to shake my hand, I will be ready. I will pull the gun concealed in my jacket. His last words will be: The worst is over.

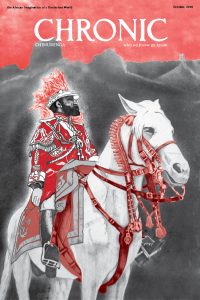

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[hr]