Christopher Wise recalls conversations and texts of the Malian author, whose deep Sahelian articulations of Islam have earned him the ire of Wahhabi Muslims and the respect of many who reject the Western imperialist militarisation and reactionary Arabist tendencies that ignore pre-Islamic Africa’s history.

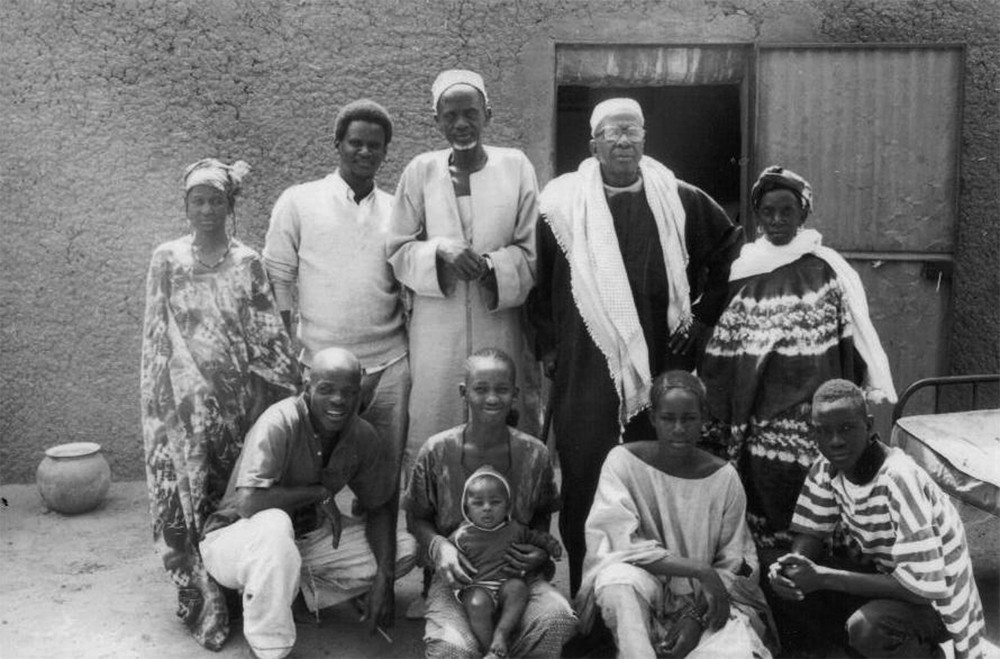

Nearly two decades have passed since I interviewed Yambo Ouologuem at his home in Sevaré, Mali in 1997. Much has happened in the interim, most notably the failed “jihad” in Northern Mali, followed by France’s expulsion of the Tuareg militants who’d taken control of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal under the leadership of the Berabiche Tuareg Iyad Ag Ghali, a Wahhabi convert and known collaborator with Algeria’s Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité (DRS) (or mukhabarat). When I put together my book on Yambo Ouologuem back in the late 1990s, my editor at Lynne Rienner Publisher urged me to come up with a title that might attract more readers than previous titles in the Three Continents Press series, which was inaugurated by the late Donald Herdeck. I had planned on calling my own book Critical Perspectives on Yambo Ouologuem, which matched other titles in the series, such as Critical Perspectives on Chinua Achebe and Critical Perspectives on Dennis Brutus.

In fact, my editor originally suggested the title Yambo Ouologuem: Postcolonial Writer, Islamic Warrior. I’d always associated the term “warrior” with Native American culture and therefore rejected it. However, I remembered something Al Hajj Sékou Tall had said to me when we’d journeyed together from Ouagadougou to Sevaré to meet Ouologuem. Tall had called Yambo a “militant”, which I took at the time to mean a devout Muslim who was deeply committed to the cause of spreading the Islamic religion.

This conversation took place about four years before 9/11. At that time, being called an Islamic “militant” didn’t mean quite the same thing that it has come to mean today. When Al Hajj Sékou Tall called Ouologuem a “militant” he meant it as a compliment, an unambiguous acknowledgement of Ouologuem’s sincerity and piety as a Muslim. The jihad that mattered to Al Hajj Umar Tall, who’d initiated the Umarian Tidjaniyya, happened in the late 19th century and seemed a faint echo from the past. For this reason, I agreed to the proposed title change of my book provided that the word “warrior” be changed to “militant”, which was the term actually used in Mali. Later, in the aftermath of 9/11, I came to regret referring to Ouologuem as a “militant” in the book’s title due to the possible misunderstandings it might engender, despite the fact that this is how the Tidjaniyya themselves referred to Ouologuem at the time of my book’s publication. (One reviewer in Pakistan was disappointed at Ouologuem’s obvious lack of “militancy” and felt deceived by the book’s title. Another complained that Ouologuem had been unfairly “labelled” as a militant with this title.)

During a visit to Bandiagara in June 2014, I sought to speak with the local Peulh chief and inheritor of the staff of Al Hajj Umar Tall, but I was dismayed to find that nearly everyone I’d met on my visit to the area in 1997 was now dead. Ouologuem was still alive, I was told, but he lived in total seclusion and was quite elderly. I sent my regards, but did not trouble him.

The eldest member of the Tall family no longer served as chief of Bandiagara as had once been the custom. Al Hajj Sékou Tall’s generation, the generation of Amadou Hampaté Ba, had now passed on and seemed a faint memory for those to whom I spoke. Moreover, the recent Tuareg war for the independent state of Azawad had devastated the local economy, which is dependent on tourism in the Dogon country. Nearly everyone I spoke with in Bandiagara was bitter about the Tuareg takeover of the north, as well as France’s dishonest handling of the Kidal region, which had left many in Mali feeling betrayed. Once again, I had reason to regret that those who might come across the title of my first book on Ouologuem might imagine that he somehow would support local Islamists like the Ansar Dine, MOJWA, or AQIM. While it is true that some Peulh or “black Arab” Tidjaniyya in Mali joined forces with the Tuareg separatists (and paid a steep price following the French military invasion), the Wahhabist jihad of Iyad Ag Ghali and his kinsmen seemed to me a manifestation of almost everything that Ouologuem – who is a member of the Tidjaniyya but also a black Dogon man – had always targeted in his various writings and public statements. If Ouologuem is an “Islamic militant”, he is certainly not an Islamic militant in the same sense as Iyad Ag Ghali and his followers.

When I first met Ouologuem, there were many aspects of daily life in the Sahel that I struggled to understand, especially those involving witchcraft and sorcery. During my interview with Ouologuem, he said to me, “When I talk to people like you I have to keep things very simple.” Only later did I come to fully appreciate what he meant, for indeed I had much to learn about life in the Sahel. At that time, I preferred to see Ouologuem as a devout Muslim writer, a pious Sufi seeking to purify Islam by appealing to its inner heart; however, I was not sufficiently attuned to Ouologuem’s identity as an African writer and man. It seemed simpler to situate The Duty of Violence in the greater context of Islamic religious practices and beliefs than to delve into the complexities of what Thomas Hale and Paul Stoller have called “deep Sahelian society”. What was missing from my initial reading of The Duty of Violence was greater reference to pre-Islamic belief systems in West Africa, which I found, upon closer examination, to have certainly influenced Ouologuem’s writings.

One important turning point for me was meeting Ouologuem’s daughter Ava Ouologuem in Paris in 2005. During a meeting at her apartment not far from Père Lachaise Cemetery, Ava asked me to lower my voice for fear that the walls of her living room “had ears”. At first, I thought Ava meant that someone might have bugged her apartment, as unlikely as this possibility seemed. Then I realised she was talking about the djinn. She was afraid that the words that we spoke might be carried beyond the walls of her apartment back to Mali. In fact, she was terrified at the prospect of visiting Mali, or at least the region in Mali where her father lived. She warned me that I should not pass through Sevaré on my way to Timbuktu for fear that enemies of her father might attack me.

That afternoon, we spoke in depth about the Ouologuem family’s involvement in sorcery. Ava told me how she herself had been possessed by one of her ancestors after drinking a potion that had been in her family for years, and that the experience had left her traumatised. She also informed me that Ouologuem’s mother, whom I’d met in Sevaré, was an extremely powerful woman, and that Ouologuem too was deeply involved in the occult. This did not mean that Ouologuem wasn’t a Muslim, merely that his approach to Islam was informed by West African traditions, many of which would be regarded as heretical in places like Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Iraq. In fact, the penalty for sorcery in Saudi Arabia is death. In The Duty of Violence, there are many references to sorcery that I’d elided in my eagerness to interpret Ouologuem as a quasi-universal Muslim writer.

As a case in point, Ouologuem told me during my second interview with him in 1997 that he sometimes conjured the dead, including prophets like Muhammad and Jesus. In fact, he spoke to the dead after he summoned them through the evocation of certain mystical sounds. I later learned that these sounds were believed to predate the coming of Islam to the region and were said to originate from the time of the ancient Egyptians. Ouologuem’s novel includes a detailed description of an act of conjuration, one that can hardly be considered Islamic. In this case, a loathsome sorcerer performs an act of conjuration during which bizarre apparitions emerge from the open vulva of Raymond Kassoumi’s mother, who is then brutally murdered.

In Abd al Sadi’s Tarikh al Sudan, a 400-year-old chronicle from Timbuktu, there is a similar description of conjuration, one that is nothing short of diabolical. In this case, an assembly of men chant the name of their common enemy while pounding upon a calabash that floats in water. After they succeed in summoning the spiritual double of their enemy, they shackle it at the ankles and then drive a spear through the double’s heart. In the Tarikh al Sudan, we’re told that the man who had been conjured in this way instantly died although he lived many miles away. In my book, Yambo Ouologuem: Postcolonial Writer, Islamic Militant, I’d described such practices as a form of Tidjaniyya spirituality and emphasised their more benign dimensions, not mentioning that many Muslims outside the region would view such practices as heretical, if not evil.

Years ago Ouologuem stated to me that “the worst enemy for blacks today are racist Arabs who have been satanically blessed with oil”. The targets of Ouologuem’s critiques – both in The Duty of Violence and in my interviews with him in 1997 – are arguably Wahhabi Muslims, who view Sahelian articulations of Islam as heretical and who espouse an ideology of blood election privileging the noble blood descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. The Saifs or “black Jews” in The Duty of Violence are not Jews who hail from Palestine, but local notables who claim to be elected because of their special Arab blood, regardless of their skin colour. This category of Muslims includes not only the Toucouleur Peulh, such as Al Hajj Umar Tall and his descendants, who also claim a blood link to the Prophet Muhammad, but many other ethnic groups in the region who profess to be Muslims, including Berabiche Tuaregs such as Iyad Ag Ghali, who led the takeover of the north in 2013.

The majority of the West African Muslims who are not Tuareg but who joined Ag Ghali’s jihad are Muslims who imagine that they are special on the basis of their noble blood identity. In Western media accounts of the Ansar Dine’s jihad in northern Mali, there has been much discussion of Al Qaeda and Iyad Ag Ghali’s indoctrination into extremist Wahhabi ideology during his time in Mecca, when he served as Mali’s ambassador. What has not been sufficiently recognised is that Ag Ghali believed that he was authorised to launch his jihad in the newly proclaimed state of Azawad because of his special status as a blood descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, or that he at least used this dubious claim to legitimise his actions. In this sense, Ag Ghali acted no differently than the Saifs in The Duty of Violence. Ag Ghali is therefore the latest avatar of the “black Jew” in the Sahel, who cynically manipulates archaic beliefs about blood nobility in order to legitimate his exploitation of the négraille (or “black-rabble”), whom he considers to be his chattel.

The term “black Jew” is well chosen in this context because the ideology of Ag Ghali and the Ansar Dine shares important commonalities with Zionist notions of Jewish identity and citizenship in Israel, which are predicated on archaic doctrines of blood election rather than residence in a particular place. In effect, the Kantian notion of one’s residence in a town (or “cité”) is eschewed in Israel in favour of occult belief in one’s birthright, literally the blood that flows in one’s veins, which is commonly construed as maternal blood. This point is worth emphasising in the Malian context because many Tuaregs like Ag Ghali and his followers have never accepted the basic premise upon which the Malian Republic was founded. In Rousseau, the social contract that leads to the establishment of the republic (or the artificial “public thing”) is null and void unless every member of the republic is considered equal under the law and enjoys the same legal rights as every other citizen. Palestinian Arabs do not enjoy the same rights as Israeli Jews because they are deemed ontologically inferior to Jews, despite the fact that both populations reside in the same territory. Tuaregs such as Ag Ghali never accepted the founding ideas of the Malian Republic, for to do so would require them to accept the full equality of all Malian citizens. On the other hand, there are many Tuaregs in Mali who reject the poisonous ideology of Ag Ghali and the Ansar Dine. Many live in Bamako where, even in the aftermath of the war in the north, they are fully integrated and productive citizens in Malian society. These Tuaregs know very well that Ag Ghali’s claims to blood nobility are as suspect as his allegiance to Wahhabi doctrine.

In the south of Mali, but also in Senegal, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and elsewhere in the Sahel, few black Africans are persuaded by Ag Ghali’s claims to blood nobility or his appeals to Arabist interpretations of Islam that are contemptuous of African traditions long predating the coming of Islam to the region. It is true that the Wahhabis have made some inroads in places like Bamako. You’ll sometimes see women wearing the black veils of the Wahhabi on the streets of that city, jostled next to the anti-Wahhabist disciples of Shaykh Amadou Bamba (at least in those neighbourhoods with a strong concentration of Senegalese). But both groups are anomalies in Mali.

The vast majority of Malians, including many Tuareg men and women, have contemptuously rejected the “jihad” of Ag Ghali, recognising it for what it is: a species of Arab imperialism that claims to bring “true” Islam to the region. If Ouologuem is an “Islamic militant,” he is therefore a militant for an articulation of Islam that has absolutely nothing in common with the Islam of the bigots who smashed the tombs of the saints in Timbuktu, who banned the music of Ali Farka Touré in Niafunké, and who destroyed the “heretical” manuscripts they found in Timbuktu. Ouologuem is a militant for a form of Islam that is egalitarian and deeply respectful of Africa’s pre-Islamic past.

What remains to be said is that the founding ideals of Mali’s Republic, if Mali is to have a future at all, must be understood, honoured, and even loved by all of Mali’s citizens, including the Arabs and Berabiche Tuaregs of Kidal. Long ago, Rousseau observed that a republic is an artificial construct, a kind of prosthetic, or iron lung. For this reason, Rousseau emphasised that the children who reside within the republic must be taught at an early age to love it. In other words, love of a prosthetic human creation does not come to us naturally. It must be inculcated.

But it is not only Mali’s citizens who must honour the founding ideals of its republic. The US, France, and Algeria must also respect Mali’s status as a sovereign nation. Many in Mali today are ready to wash their hands of the Kidal region, not because they want to see Mali split in two, but because they are sceptical that the US, France, and Algeria will ever release their iron grip on the north. Over the years, Muammar Qaddhafi invested millions of dollars in Mali’s development, especially in Bamako. Yet, Qaddhafi was raped with a bayonet before he was brutally murdered without trial, following US airstrikes on Libya. Ironically, the US justified its lack of respect for Libya’s sovereignty on “humanitarian” grounds. (This was before then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said of Qaddhafi’s rape and illegal killing, “We came, we saw, he died…”)

If the postcolonial nation state in Africa is crumbling, if the nation state in Africa is little more than a failed project of European imperialists, this is so because the West itself seems to have little interest in its preservation. If a fraction of the US dollars spent on AFRICOM in the Sahel were diverted into educating Mali’s children, the Republic of Mali might have a chance. At the conclusion of Ouologuem’s The Duty of Violence, the Saif demonstrates his willingness to be a full player, to abandon recourse to extra-legal violence, and to participate in the postcolonial game. (In the novel, Saif tosses the serpents he uses to assassinate his enemies into the fire while playing a game of chess with the French Bishop Henry.) With the exception of outlaws like Ag Ghali, who are supported by external agents, most Malians – including many of its Tuareg citizens – are eager today to repair its damaged republic and look now toward a brighter future. This can only happen if foreign powers like the US and France, with their many “interests” in the region, respect Mali’s sovereignty and choose to invest their time and money in educating Mali’s children, not in arming the region.

This story features in the Chronic, published April 2015, an edition in which we ask: what if maps were made by Africans for their own use, to understand and make visible their own realities or imaginaries? How does it shift the perception we have of ourselves and how we make life on this continent?

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop. Copies coming to your nearest dealer now-now. Access to the whole edition and Chronic online archives is available for $28 for one year.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurenga-shop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button] [button link=”https://chimurengachronic.co.za/online-subscription” color=”black”]Subscribe to the Chronic[/button]