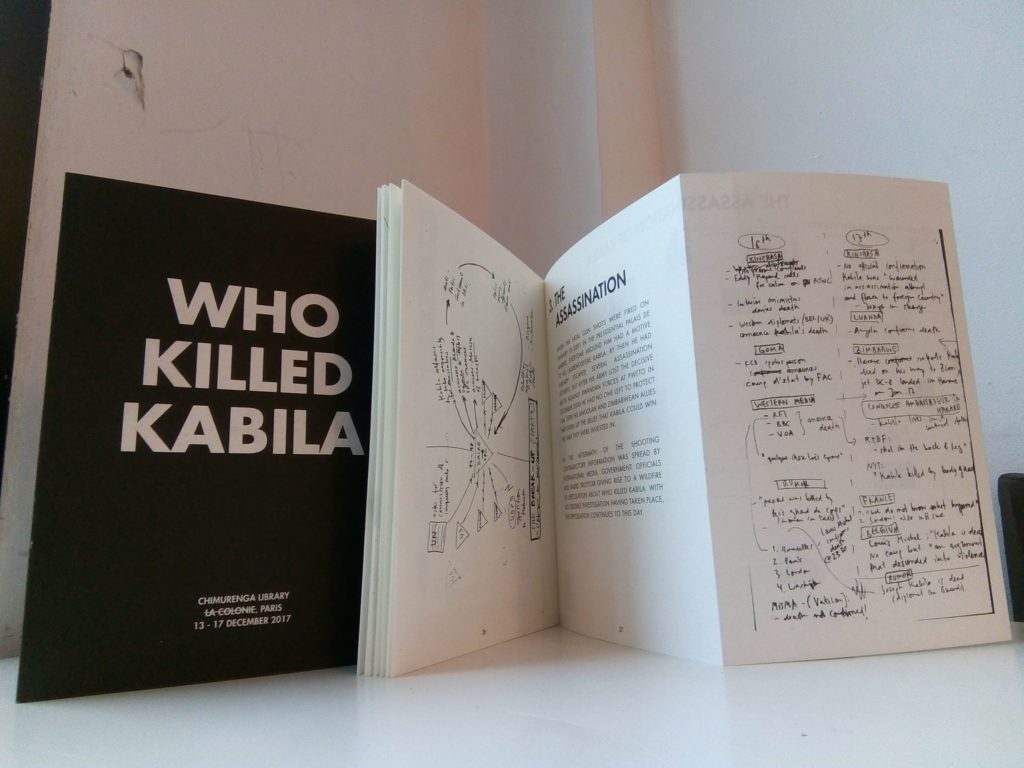

On January 16, 2001, in the middle of the day, shots are heard in the Palais de Marbre compound, the residence of President Laurent-Désiré Kabila. The road bordering the presidential residence, usually closed from 6pm by a simple guarded barrier is blocked by tanks. At the Ngaliema hospital in Kinshasa, a helicopter lands and a body wrapped in a bloody sheet is off loaded. Non-essential medical personnel and patients are evacuated and the hospital clinic is surrounded by elite troops. No one enters or leaves. RFI (Radio France International) reports on a serious incident at the presidential palace in Kinshasa.

Rumor, the main source of information in the Congolese capital, is set in motion. News spreads like wildfire in the city. Communications are interrupted. A Jeep equipped with rocket launchers takes position in front of the largest mobile phone company, STARCEL. At the RTNC (Congolese national radio and television station), the programs continue normally until Colonel Eddy Kapend, appears on the screen, haggard eyes, dry lips, in a dry and authoritarian tone orders the military to keep the troops calm and to close all the borders of the country. He gives no explanation. He promised more later but does not reappear until much later on January 23, 2001, when he is captured on camera in the guard of honor at the official funeral of President Kabila.

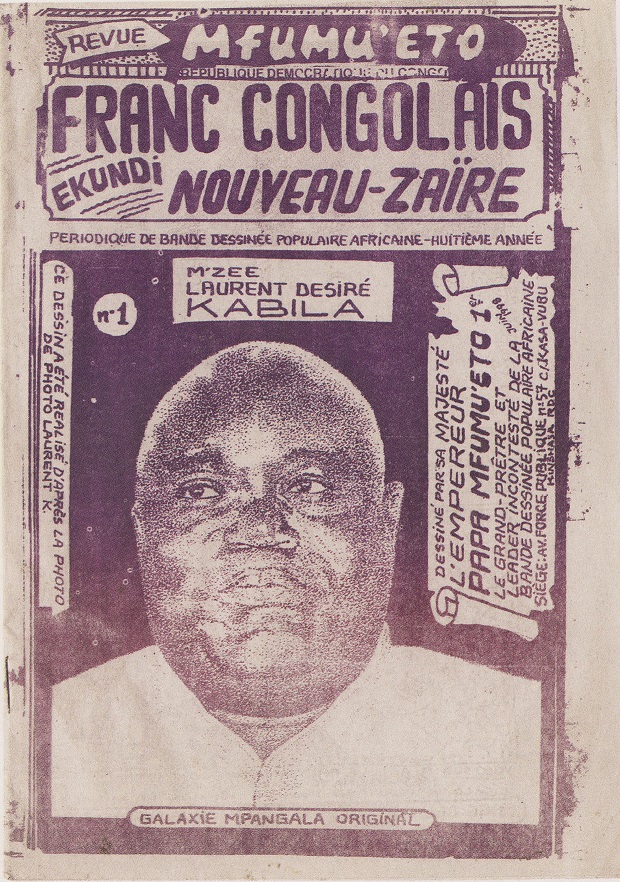

A communication war begins. Officials in Brussels, Paris, London and Washington, citing credible sources in Kinshasa, successively announce the death of Kabila at the hand of Rashidi Muzele, one of his bodyguards. Kinshasa admits to the shooting but says that Kabila was wounded and is receiving medical treatment outside the country. Zimbabwe, an important ally of the Congolese government, announces the death of the president before retracting. On January 18, 2001 at 8pm, live on national television the Congolese minister of communication, Dominique Sakombi Inongo announces the death of Mzee Laurent Désiré Kabila on that day (18 January 2001) in a Harare hospital in Zimbabwe.

The official investigation that follows fails to finger a single suspect. 135 people – including 4 children – are arrested and tried before a special military tribunal. The alleged ringleader, Colonel Eddy Kapend, and 25 others are sentenced to death in January 2003, but not executed. Of the other defendants 64 are jailed, with sentences from six months to life, and 45 are exonerated.

Les Rumeurs

So, who killed Kabila? Almost 15 years later rumours still proliferate. Suspects include: the Rwandan government; the French; Lebanese diamond dealers; the CIA; Robert Mugabe; Angolan security forces; the apartheid-era Defence Force; political rivals and rebel groups; Kabila’s own kadogos (Swahili for child soldiers); family members and even musicians.

The geopolitics of those implicated tells its own story; the event came in the middle of the so-called African World War, a conflict that involved multiple regional players, including, most prominently, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe.

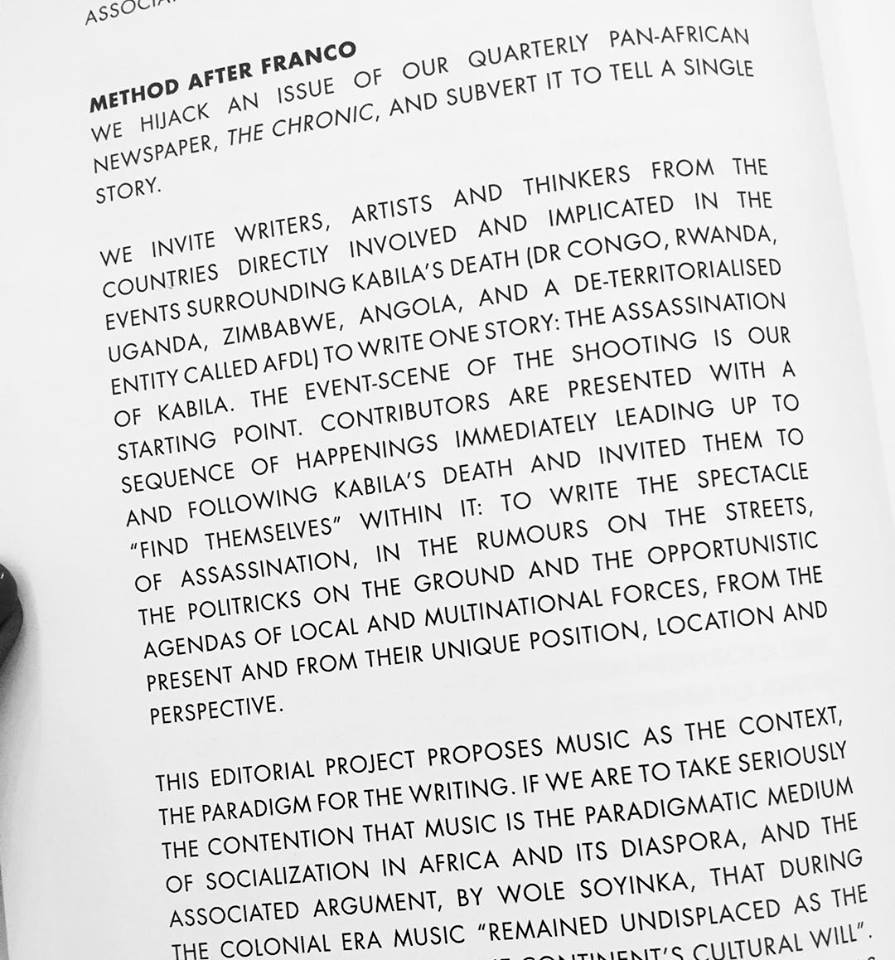

How then does one write this story? How does one write history when the official “truth” is itself suspect; when rumour has replaced fact as the most reliable form of knowledge production; when knowledge can only ever be tentative, contingent, and situated; and when faced with a cacophony of voices and multiplicity of narratives?

It cannot, it seems, be told as one story. Novelist Chimamanda Adichie has warned us of “The Danger of a Single Story.” Our lives, our cultures, our histories, Adichie tells us, are composed of many overlapping stories. Adichie’s idea is neither novel nor singular. In the 20th century “One” became a target for philosophical attack, on different levels of sophistication, which include liberal apologies of pluralism in politics and epistemology.

But, as recent history has vividly shown us, in these ideologies, the absolutes often remain, albeit in an inverted form: democracy, individuality, freedom of conscience and of course ethical choice (partly inherited); in the discourse of human rights, the absolute authority of government, totality, orthodoxy, and supreme good which they oppose.

Who killed Kabila? This issue of the Chronic presents this query as the starting point for an in-depth investigation into power, territory and the creative imagination by writers from the Congo and other countries involved in the conflict.

To purchase available copies head to our online shop or visit Chimurenga Factory at 157 Victoria Road, Woodstock.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.