by Binyavanga Wainaina

(image by Aimé Ntakiyica)

Who invented that piece of nonsense called truth? Tired of truth, I am. And metanarratives and more truth and postcolonies. An intellectual world in which each paper rewrites its own perceptual framework; everybody is represented, nobody is real. Sick, I am, of affirming stories about strong brown women; of being pounded into literary submission; patronised beyond humanity. I miss beginnings, middles and ends. Please bring back the myths and legends – even those ones about wise rabbits and wicked witches.

Nothing is true. Pick and choose your way. And it helps that there aren’t simple direct ways to places. There are gritty things, hinges to doors we do not want to open, that we want sealed, buried under the vast amount of cowshit we are shovelling in print onto our continent. Lets have things tested again: maybe sang, like Fela did; like Nesta did. If your thing cannot fit into a song, just shut up.

What is the test? Ideas aren’t democratic – the value of your ideas can’t be measured by how many people understand them. That is nonsense. And though they have to fit into something, a system, there’re no straight lines or building blocks. Only just webs, interlinks that feed themselves and lead into each other and go nowhere… Which writer on this continent has started a movement? A series of aesthetics that have influenced a generation somewhere? A movement that has burned on its own fuel?

I am obsessed, at this point, with a conversation with myself. Writing, a vain pursuit. Everywhere, everywhere, boxes are imposed. Responsibilities. Who is your audience? Who are you writing for? Why are you not writing in your mother-tongue? Art is never for art’s sake, you tell yourself. Of course it isn’t. But art for art’s sake is a necessary lie. Who has perfect knowledge, mastery over their imagination? I can’t be, nor do I want to be Mr. AllPanAfrica when I write. As a reader, detest the contrived. I do. The writing that comes with answers before it starts to write. Hate fiction that uses a hammer to ram its message into your head. Why not sing a protest song? Fiction is about creating worlds, if you do not want to do this, go write a thesis.

My country, Kenya is forty years old. This century, we have only had two seasons of national unity – both lasting only a few months: Independence and the 2002 elections.

What many in and outside Kenya know as tribes, did not exist as nations before the white man came. The contracts were different, the social arrangements different. Languages were shared, and agreements, and rules. Tribal self-awareness came when people needed to deal with the British, in structures the Brits could recognise and talk to. The Miji Kenda, Kalenjin, Gikuyu: all words used in the twentieth century to describe peoples who had similar lifestyles and spoke similar languages.

Jomo Kenyatta took the game further when he invented a certain Gikuyu. Before he wrote Facing Mount Kenya in England, most of us now known as Gikuyus could not agree on our origins, on how many clans there were. Some said we were descended from the same, some that Gikuyu and his wife Mumbi were the first Gikuyus, and that their nine daughters formed the nine clans. Some insisted the clans were thirteen, some said five. His version of Gikuyuness, a mix of missionary education and the experiences of his own village life, became the idée fixe. Now, we look to his book to find out how to perform wedding ceremonies, to settle debates. Gikuyus, once the most decentralised of decentralised communities have become raving nationalists. They believe Kenya is their baby: they fought for it, liberated it, built it; an the rest of Kenya is intruding on what was a fine Kenyatta-designed arrangement.

And how do you create a nation out of forty or so tribes? You spend time, as frenziedly as possible over forty years, building a weave of mythology strong enough to bond the pieces together: a grammar, a constitution, mottos – you fail to do this successfully: only blood creates nations. Only the risk of annihilation makes people abandon what ways they presently use to make sense of the world. But you must try to make this work – we know no other way, so we pretend it works. And wait and see. And become born-again Christians or drunks if, when things take the wrong course. A young nation is a bad novel: contrived, trying to push an agenda that cannot persuade readers, trying to impose a tight structure that excludes all reality. The English were beaten into submission before democracy took present day root; tribal sentiment was beaten out of them; religion embossed in blood; the State fought and beat all comers to establish a complete monopoly of violence over its citizenry. Only then were individual freedoms possible. Yes Yes. Bad medicine. Lets pray nationalism will die soon, and something more gentle will come by and massage us gently to prosperity. Don’t hold your breath.

Uganda, my mother’s country, has abandoned complex funeral rites. Kenya, more modern, Western, less Christian, still sticks to traditional funerals, sometimes mixed with Christian services; this lasts days, sometimes weeks. So many Ugandans died from AIDS in the late eighties that it became impossible to justify the expense and time to organise a proper traditional or religious funeral. These days somebody dies, and he or she is buried the next day. So far everybody seems comfortable with the idea. But then, you see, Uganda has done the genocide, the civil wars, all the blights that built Europe. It will do what it needs to. And will make the grammar to justify it.

In Kenya we veer from ecstasy to despair. Open societies come with their stresses. Just as people held themselves back, held back their creative instincts in the Moi days; old unresolved hates, and grudges that were in suspension for a while have risen to the surface. We have a gormless president – and without anybody selling us dreams, we hang in a vacuum, and are only able to deal with each other at a political level in the old ethnic alliance ways, complete with emerging Godfathers. To be honest, we miss the day when government was opaque; when power was centralised in one man. It is starting to seem that corruption was more manageable then.

Francois Mauriac said, “there is no such things as a novel which genuinely portrays the indetermination of human life as we know it.” I wonder about this statement. It seems to me that man is adept at fiction. We use the same rhetoric to build nations, justify wars, bond families, make marriages work, keep the attention and loyalties of our cliques. Narrated by any Kenyan you ask, the story of Kenya will not seem different from a historical novel. Characters will rise up; there shall be titanic conflicts, climax’s and resolutions –the amalgamation of tiny incidents that actually took place are indigestible; and more importantly, dangerous.

Computers are fortunate. As the software needed to get things done starts to grind down the hard-drive, the body, one only needs to invest in a better computer which can accommodate new technology. I have in mind somebody from the 1950s, in sepia, running at great pace, as technicolour sweeps up behind him: the story of our times.

Kenyans are simply muddling along, as human beings do, insisting on learning everything the hard way. We live in times where we are all associated, in realtime, with everything that everybody in the world is doing; we are aware of the rest of the world. But we sit here, in our 486 computerbodies, watching a world where people speak in gigabytes. With the exception of time, as taught to us, life provides no highways. We make them, we call them habits. And these paths are often changeable, adaptable. The most stubborn of them are those highways found and drawn in our minds when we are children. Small things, as solid as matter, we keep inside of us to protect us from facts, from the fact that we are tiny things suspended in an enormity we cannot digest or comprehend, and threats can come from anyplace.

As a child, I learnt to love novels. They took hold of me at the time the acquisition of language was important: trying to name the world and its incidents. By the age of ten, I had learnt to sniff out the useless long descriptive passages, and ignore them. Take the marrow. I more or less kept up this pace. It only reduced when in my twenties I became infatuated by writing.

So part of me is Europe. A place where Man has become his own God, looking down at Himself, and shaking His head sadly. But because God the Man and Man the Man are the same person, they are at an impasse. I have read too much to escape being that kind of a person. So have many Africans. So have many people around the world, who are fixed into their past, who cannot adapt. And people who may be seen in other times as near inhuman can take advantage of our times, sublimely, because they are able to blankslate themselves. They are able to change in a world where changing fast, and without baggage, is a mark of the Hero. David Beckham. The more successful ANC activists were those who were quickly able to shed their past and embrace Randburg…and all it stands for.

Nairobi is full of people born generations away from a mud hut who drive into the city every morning, cassette player blaring with motivational tapes, trying to get themselves formatted for work and life and success. Most of the social effort: where you drink, how you plan your décor, where you drink, what you talk about when you drink – all planned to fit into a template that you were not brought up in. Many, most even, are unable to blankslate themselves. They fail, and nobody has sympathy. My peers have friends they have known all their loves. But only in English. When somebody dies in one’s family, your friends do not come. They do not know, or want to know you in your mother-tongue, that vast part of you that cannot present itself in a Nairobi bar remains yours and your family’s.

I wonder sometimes, whether the main problem with the educated classes of our continent is simply this: we want our continent resolved in our own lifetimes. And our continent is not interested. So we contort, and twist ideas around, and blame and create whole new disciplines to understand and explain when maybe all that is required of us is to document, to simply document our times if we are writers, document in the flawed way that seems true to us in our individual hearts, instead of superimposed with that vile censorious correctness that means nothing, and does nothing, and only makes middle class Africans feel better about themselves. What matters, what will be useful, will resolve itself it its own good time. And you can be sure it won’t be the literature about the brown strong woman who empowered herself without human quirks. I speak here specifically about the writer Edwidge Dandicat whose novels I cannot stand; and other writers of her school.

Do I know what I am saying?

No?

Okay.

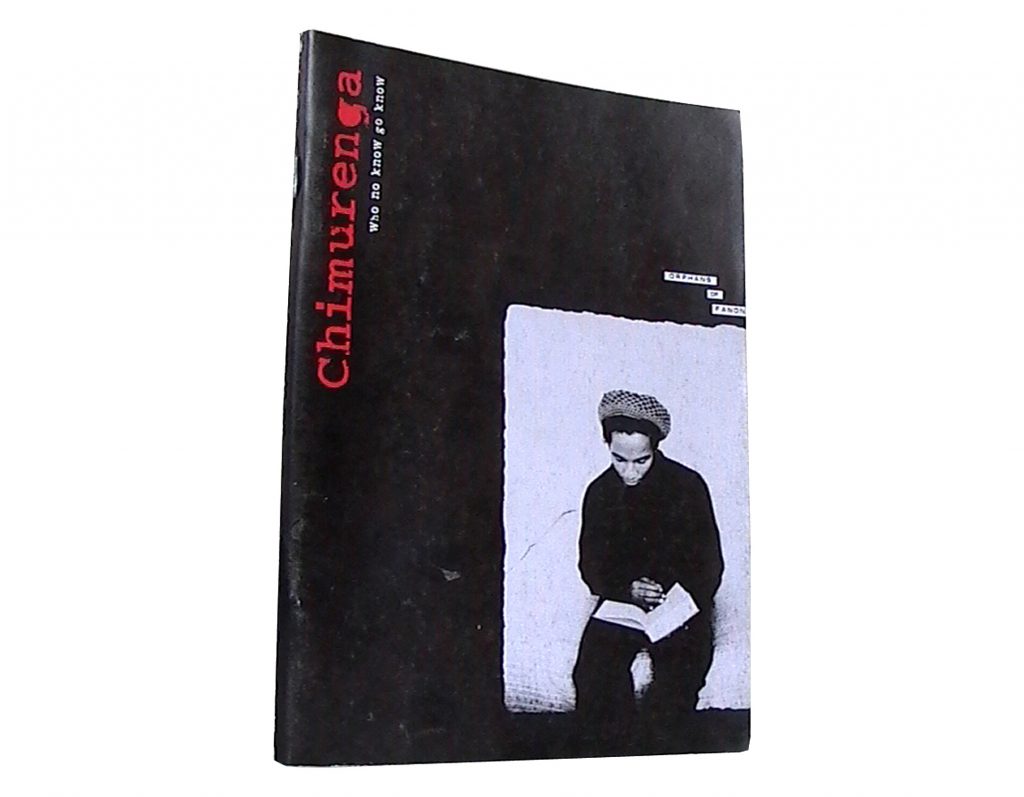

This story, and others, features in Chimurenga 06: Orphans of Fanon (October 2004), A series of conversations, real and imagined, on the “pitfalls of national consciousness” by Mustapha Benfodil, Achille Mbembe, Charles Mudede, Fong Kong Bantu Soundsystem, Robert Fraser, Branwen Okpako, Leila Sebbar, Binyavanga Wainaina, Laurie Gunst, Olu Oguibe and many others

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work