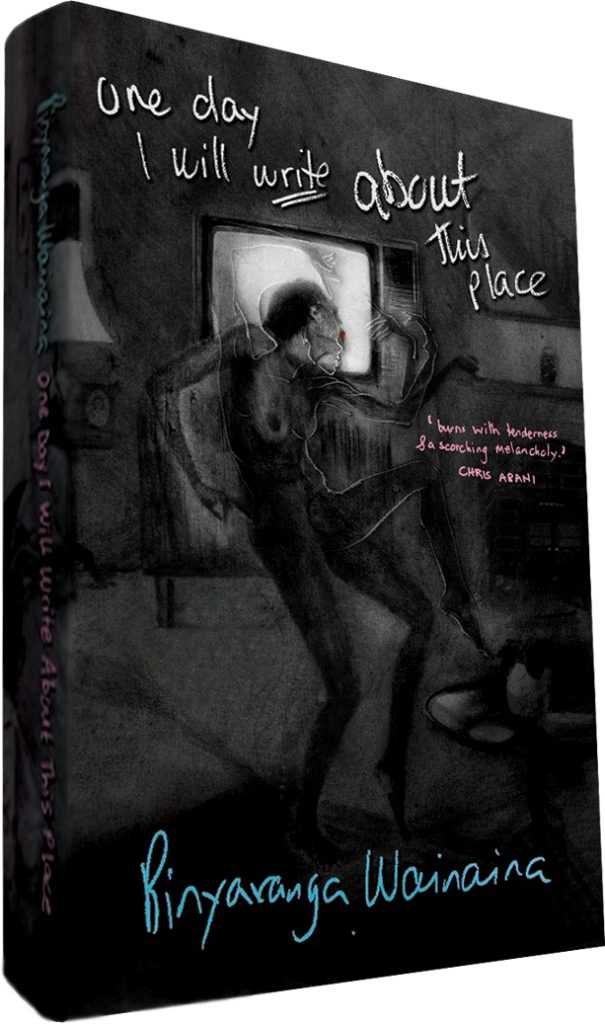

by Keguro Macharia

Binyavanga Wainaina

Kwani Trust, 2012.

1. The Whereness of Binyavanga Wainaina

Bracketed and intersected by 9/11, Mwai Kibaki’s ascent to power, Kenya’s post-election violence, and Barak Obama’s election; written primarily during Binyavanga Wainaina’s residence in the US, or at least away from Kenya; set in Kenya, Uganda, South Africa, Nigeria and the US; and marked by sounds from Congo, South Africa and the US, along with the Kenyan benga; and shifting, frequently, between the confessional and the ethnographic, the nativist and the cosmopolitan, the national and the postnational, how might one describe where One Day I Will Write About This Place lives as it travels? What geo-histories are appropriate to read One Day? Is this a Kenyan book? An African book? An Afro-diasporic book? A New York book? A post- 9/11 book? A Post Election Violence book? A South African book? Despite Wainaina’s occasional (toobrief) forays into Kenyan rurality-as-development, One Day is not quite as ‘son of the soil’ as recent winners of Kenya’s book prizes. And the reader looking for ‘Kenyan’ literature, especially as defined through Kenya’s bookstores and literary prizes and school curriculums, comes away from One Day with a sense of bewilderment, sure that an experience has taken place (that of reading), but not quite sure how to frame or narrate that experience.

Do terms such as ‘transnational’ or ‘world literature’ suffice to describe One Day’s multi-geographies and multi-histories? And how do such terms function in Wainaina’s local-making project? A remarkable feature of One Day is how local every location becomes; rarely is Wainaina rooted or rootless, rather his work ‘makes local’, to use a necessarily awkward locution.

The whereness of Wainaina’s work is as much about the geo-histories it inhabits as it is about the critic/ reviewer’s desire. I started writing this while in Kenya and, though I had a copy of the book before I left the US, I read it in Kenya and on the plane – forget whether I was heading to or returning from Kenya. I’m writing this from a friend’s apartment in Washington DC, and, from here, some of the certainties I had about One Day feel more tenuous. From here, I am compelled to ask how it might speak from, and as, a diasporic work. Because context matters, I should also confess that I am working on an article about the diasporic nature of African fiction. These are my taints.

A recent call for papers asks (belatedly) what would happen if we moved the centres of black diasporic action and interaction from European and North American cities to locations in Africa; from, say, Paris or New York or London to Lagos or Kampala or Johannesburg? As one reviewer notes, One Day continually returns to Nakuru. In conversation, Wainaina compels me – and other Nairobi provincials – to re-imagine Kenyan geography from a Nakuru that is more than a stop on a school vacation trip to look at pink flamingoes (the real ones, not the charming plastic ones on US lawns). I know Nakuru as the place where very good family friends lived, a place where the fish was abundant and wonderfully fresh. And though I knew the president had a house there, Nakuru never really figured in my imagination of Kenyan cosmopolitanism.

To reformulate an earlier question: what would world literature look like if it started from Nakuru? What would transnational literature look like? What happens if sites otherwise described as too local to be national or regional or international assume the weight of their histories and localities? (A friend is writing an epic poem focused on Lukenya that I suspect will change how we imagine Kenyan microlocalities once they are embedded within their global histories.) And what would it mean to read One Day as world literature?

Although I am convinced that the question of One Day’s geo-histories is more or less an academic one, it would be a mistake to reduce its stakes to another book, or article, or class, or conference. I have been thinking about the stretch it demands – the stretch that is so often disavowed by readers and critics. Although much of the book focuses on Wainaina’s childhood, I’m intrigued by all the reviews that highlight the magical childhood and gloss over the troubling young adulthood filled with depression, itinerancy, indirection and vagueness. Wayward, unfocused children can be delightful, but wayward youth are not, especially so when that youth leaves a specific space and travels to become the troubled immigrant youth of here and there and elsewhere. How does one read the geo-history of wayward youth as it moves through and beyond picaresque geographies, not suturing a nation or being molded into a citizen-character, but morphing with each new encounter?

I have said more about ‘geo’ than I have about ‘history’. Except to mark where I have written this. I completed it from my new apartment in Baltimore as I prepared to go into DC to celebrate the New Year with friends. It is traced by the New Year I will not be spending in Nairobi; the weeks I wrote it while in my Spring Valley apartment; the airports I shuttled through writing and editing (JKIA, Dubai, JFK, BWI, National); and the many people who made Nairobi wonderful and who have welcomed me back to the US with love and care. It is these geo-histories of movement and stasis I bring to One Day, delighted to find in its itinerancy the familiarity of disorientation.

2. The sounds of things, tings and manythings

First always comes the ability to believe, and then the need to.

– Carl Phillips, All it Takes atmospheres are sonically saturated

– Gayle Wald, Soul Vibrations

Despite the uncertainty that runs through One Day I Will Write About This Place, the final sentence suggests something of the accomplishment of the bildung: ‘We fail to trust that we knew ourselves to be possible from the beginning.’ At the end of One Day, the insistent, fissured ‘I’ that runs through the narrative dissolves, through benga, into a collective ‘we’. The individual has been folded into the sound of independent dissonance: ‘Right at the beginning, in our first popular Independence music, before the flag was up, Kenyans had already found a coherent platform to carry our diversity and complexity in sound.’ This is because: ‘Any good benga guitarist can mimic the architecture and musical rhythms and verbal sounds of any Kenyan language. Stripped down, that is the intent of benga’. At the end of One Day, Kenyan-ness becomes available as a shared cultural property, available through the soundings of benga.

How might one engage this turn to sound as suture or ‘vernacular glue’? More broadly, how does sound function in One Day? It is a work suffused by sound, often confounding the line between the written and the aural. Listen:

One bee does not sound like a swarm of bees. The world is divided into the sounds of onethings and the sounds of manythings. Water from the showerhead streaming onto a shampooed head is manything splinters of falling glass, ting ting ting.

All together, they are: shhhhhhhhhhh Shhhhh is made up of many many tinny tiny ting ting tings, so small that clanking glass sounds become soft whispers; like when everybody at the school parade is talking all at once, it is different from when one person is talking. Frying sausages sound like rain on a tin roof, which sounds like a crowd.

And my favourite:

Take the sun – give it a ten thousand corrugated iron roofs – ask it, just for the sake of asking, to give the roofs all it can give the roofs and the roofs start to blur; they snap and crackle in agitation.

Corrugated iron roofs are cantankerous creatures; they groan and squeak the whole day; as they are lacerated by sunlight, their bodies swollen with heat and light, they threaten to shatter into shards of metal light. They fail, held back by the crucifixion of nails. To read One Day, one must be what Alex W Black describes as ‘a reader who has an eye for sound’.

Music is only one part of the rich soundscapes One Day encounters and records: though it does more than record as it works through immersion. One is plunged into sound – cast into the centre of ‘manythings’ that do not coalesce (or fissure) into music or speech, but render, instead, the vibrations that resonate in and through bodies. One Day asks how attending to shared quotidian soundings – the sound of bees, the crack of corrugated roofs – might offer strategies for plotting belonging. What might it mean to share the experience of sound, to be lost in its multiplicity, to vibrate to shared frequencies? Certainly, when he writes ‘ting ting ting’ I hear not only the corrugated roofs he suggests but also the sound of Gikuyu guitars and the sharp-edged patois that transforms ‘thing’ into ‘t’ing’. Cultural and historical contexts multiply and coalesce into a manything, a ‘soundthing’ of impossible chord/cord formations – strings, musical notes, muscles, and the promiscuous histories of all these.

I am interested in the ‘gaps’ between noise and music in One Day, before it gets to the ‘resolution’ of benga. I am wary of terming ‘ting ting ting’ and the other sounds in One Day music, though they are in the same neighbourhood. Other sounds saturate our spaces and it is these I’d like to note. I am interested in how sound in Wainaina’s text is not simply background or distraction from the urgencies of narrative, but an intervention into how we conceive of narrative movement. I am interested in how popular music produces memory aslant to that sanctioned by the state, and also how it registers ongoing ambivalent encounters with modernity in its hybrid and syncretic forms.

In the 1950s, John Low argues, ‘guitarists in Kenya were often viewed by the authorities as troublemakers, debauchees and rebels.’ They ‘represented a threatening kind of change’. Part of this threat arose from the multiple traditions guitarists drew from and combined: musical styles from South America, South Africa, Malawi, Zaire and Nigeria, all routed through ethnic soundings – the drum, the horn, the nyatiti. From one perspective, guitar music represents the most syncretic of all Kenyan musical forms. At a time when various ethno-nationalisms were taking root in Kenya, guitarists presented alternative soundscapes, offering proliferating dissent as the state tried to create a lined up Kenyanness. As one of these syncretic manifestations of dissent, benga created multiple opportunities for engagement. Rooted in nyatiti soundings (those Wainaina fears early in One Day), it localises a cosmopolitan practice (guitar playing), creating a rooted cosmopolitanism, to adapt Kwame Appiah’s language. As it circulates away from communities who understand the languages it is produced in, it assumes a different role, as its rhythms, its soundings (as opposed to its lyrics) enable creative forms of movement in the form of dance. Differentially hued spaces are created within similar soundscapes.

Tellingly, Wainaina is interested in the sound of benga: how it renders language both legible and irrelevant. The final line of One Day reads: ‘We fail to trust that we knew ourselves to be possible from the beginning.’ It is a difficult line, perhaps an impossible one, as it moves from belief, to knowledge, to possibility. I get snared (and scared) thinking about how it means.

I have been reading Carl Phillips and he continually returns to the relationship between ability and need in the sphere of belief; or, more concretely, he returns over and over to belief. In a book that is tethered to the promise: ‘I decide that one day I will write books’; ‘One day, I will write about this place’ – and one that hiccups over the post election violence of 2008, it is probably not unusual to see an argument made for belief, even as Phillips’s terms keep nagging at me: ability and need.

If there is a bildung structure to One Day, it is in how ability and need become anchored in the person of Binyavanga Wainaina. His possibilities, hard-won, suggest, as they must, something about Kenya’s possibilities. I wince as I write this because it sounds too flat: not easy, but I wanted something sexier. Perhaps to say: in One Day belief is a manything.

This story, and others, features in the Chronic (April 2013). In this inaugural issue of the Chronic, stories range from investigations into the business of moving corpses to the rhetoric of land theft and loss; latent tensions between Africa’s most powerful nations to the soft power of the biggest satellite television provider; and the unspoken history of Rushdie’s “word crimes” to the unwritten history of PAGAD.

To purchase in print or as as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work