Gwen Ansell maps the distance between words and music, fiction and autobiography, subversion and submersion through an epistolary review of two books that operate at the limits of language and song.

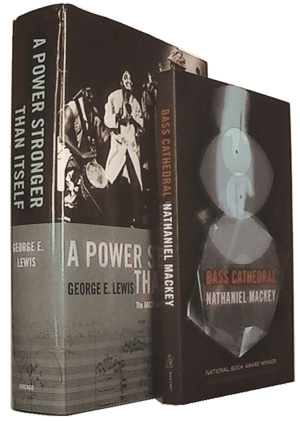

A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music

George E. Lewis

University of Chicago Press (2008)

Bass Cathedral

Nathaniel Mackey

New Directions (2008)

“According to my records there was something/More…mind bringing African control on the corny times/of the tunes he would play. There was Space/And the Sun and the Stars he saw in his head/In the sky on the street and the ceilings/Of nightclubs and Lounges as we sought to/Actually lounge trapped in the dull asylum/Of our own enslavements. But Bird was a junkie.”

– from “Historiography” by Lorenzo Thomas

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture”

– Thelonius Monk

Dear Edgar,

Thank you so much for your email inviting me to co-author an article on the life of Johnny Swallow, the late Sophiatown alto saxophonist. I’ve read the proposed outline you attached, and though I’m certainly interested in the project, I think we have a debate here about treatment – so let’s talk.

I like your idea of an almost cinematic cross-cutting of semi-fictionalised biography and analysis. But then we get to your first vignette: Johnny Swallow’s death – alone, amid broken bottles in an empty, stinking hovel – the only sign of his craft a battered sax lying on the table next to a half-empty whisky bottle. First, it’s not accurate: Johnny Swallow died in a Soweto hospital bed, surrounded by family and bandmates (some of whom he was cussing with his dying breath for their commercialism).

Second, there are echoes in this framing of all kinds of cultural criticism we ought to be questioning: the image (seeded by Romanticism and reworked by Ross Russell, Norman Mailer and the ‘Beat Generation’) of the artist – and especially the black artist – as an instinctual, solipsistic creature, driven toward destruction by his – and it’s almost always his – monstrous passions, barely in control of his choices, with the inevitability of death virtually a precondition for his creativity.

That’s been a destructive assumption about jazz music-making for too long. Have you read George Lewis’s book, A Power Stronger Than Itself: the AACM and American Experimental Music? At 600- odd pages it’s a massive tome, but one of the striking things about its discourse is how it subverts that assumption.

When I talked to Lewis about the book, he told me how it was more than a decade ago, “sitting in a meadow in Umbria, looking across a field of sunflowers” that he began listening to the tapes that form its heart.

Lewis, currently the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music and Director of the Centre for Jazz Studies at Columbia University – and also a trombonist, digital and instrumental composer and member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) – said he’d already written about the Chicago AACM in scholarly articles.

But when he reviewed tapes of the mid-1960s founding meetings of the AACM, meticulously preserved by founder-member Richard Muhal Abrams, “Right then, I realised there was a book in it.” He heard painstaking discussions of the meeting process, organisational rules and musical policies. These “tropes of structure and order” had so far found no place in American musical historiography, “where transgressive black music practices are characterised as bad or mad, but where transgressive white ditto are described as avant-garde”.

Lewis’s book breaks new ground in its structure and process. His participatory approach lets AACM members present competing as well as complementary memories and evaluations. The text combines archival study with ethnography and the telling of compelling human stories of individual AACM members: what music researcher Brent Edwards calls “the autobiography of a collective”. And it concludes with an imaginative, improvised “ring shout” chapter based on the diversity of testimonies and experiences his research had amassed.

The AACM, now almost 50 years old, with branches in both Chicago and New York, is still a living expression of the politics of self-reliance. Its explorations of multimedia platforms and of debates such as that on innovation versus canonical repertoire predated those of many other groups, and opened the door for, among others, Asian-American musical experimentalism. These, in addition to its collective practice and rejection of the ‘great man/heroic soloist’ historical – and jazz – discourse, find echoes in the process as well as the content of the book. The AACM was about far more than jazz (it created a collectively managed platform for all types of original experimental music), but its narrative remains a jazz story, because it reflects, says Lewis, “the bedrock jazz values: resistance to oppression, mobility and the right to speak out”.

When you talk to Johnny Swallow’s bandmates, you’ll hear a similar discourse – about a man who was a stickler for precision and detailed rehearsal; a demanding and effective mentor; and erudite about all kinds of music and articulate about nationalism and the struggle. I don’t see too much of that in your outline, and I wonder why?

Let me know what you think

G

[excerpt from A Power Stronger Than Itself]

Hi Edgar,

Thanks for the rapid response. Yes, okay, maybe, as you say “Drama, heroics and romance are what readers want from a jazz story” – and, to editors, that tends to mean foregrounding an individual. But George Lewis constantly talks about jazz improvisation as a collective process; it really doesn’t work well unless, as he says, your fellow-players have “got your back”.

Another of the jazz writers I like, Nathaniel Mackey, would turn your approach on its head. He said: “To me it’s more the work finding or defining, proposing an audience, than the work being shaped out of … consideration of an audience: ‘this is what such and such a group of people wants to hear…’”

But still, a story about jazz has to be more than a list of facts. There is magic in music; it invokes and signifies the experience of its makers and hearers and sparks off other memories, ideas and desires. So how can our story of Johnny Swallow avoid romantic excess but retain that sense of what Anthony Braxton called “the beauty and wonder in the discipline we call music?”

Maybe we can find some answers in Mackey’s own book, Bass Cathedral, published around the same time as A Power…. It’s an epistolatory novel (so I suppose this correspondence is a clod-hopping kind of homage) and fourth in the series From a Broken Bottle, Traces of Perfume Still Emanate, that chart the fortunes of an improvising collective, Molimo m’Atet. In Bass Cathedral, they’re preparing and releasing their new album, Orphic Bend and working on new material.

Mackey’s poetry has won several awards. He’s Professor of Literature at the University of California Santa Cruz, a former editor of the literary journal Hambone and deejays a world music radio show, Tanganyika Strut. So it’s no surprise that the writing in Bass Cathedral spins on the tickey of words: their musicality, mutation and metaphoric resonance – and how far they can be stretched. As the band stretches out on a new piece, “the violin gave an orphic underpinning, a black-orphic boast of being on intimate terms with the sun. It all added up to metallic bluster, chest-on-chest insinuation, cosmic armour, solar explosion made charismatic by sostenuto string.” And yet this soaring verbal improvisation is grounded in a solid understanding of musicians’ lives and concerns – from the comedy of interrogating hapless record-store clerks to find out who’s been buying Orphic Bend, to the technical philosophy of whether a particular musical concept will speak more clearly on reed or brass.

Listening to the test-pressing of the album, the band notices a cartoon speech bubble materialising in the air: “I dreamed you were gone…”, it says, charting string player Aunt Nancy’s memories of her father. The bubbles reappear unpredictably; at one performance they urge the audience to a lascivious groove that “delights but also dismays” the band struggling to dismantle the 4/4 shuffle and recapture the music’s original intention. The speech bubbles become fantastic creatures; mischievous metaphors for what music can say and do.

There are ways of writing about jazz and jazz players that capture the magic far better than the infatuation with how many bottles/how many fucks? Mackey has found a gorgeous one and his approach ought to challenge the chroniclers of South African jazz to find our own.

As Mackey puts it: “I have read people whose work made reference to things that I didn’t know about, and reading that work has been an impetus for me to find out. Since that has been my experience as a reader, why wouldn’t it be the experience of others? One doesn’t have to be constantly looking over one’s own shoulder asking: ‘Can I say this? Is the reader still with me?’ I think you have to go with the faith that there are readers who are with you. You may not know who or where they are but you have to take that risk.”

Yours in writing,

G

[excerpt from Bass Cathedral]

This story, and others, features in Chronic Books, the review of books supplement to Chimurenga 16 – The Chimurenga Chronicle (October 2011), a speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present. In this issue, through fiction, essays, interviews, poetry, photography and art, contributors examine and redefine rigid notions of essential knowledge.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.