by Koketso Potsane

Art has always been used to make statements about what is happening. In his article “Reciprocal Bases of National Culture and the Fight for Freedom,” Frantz Fanon argues that extreme ways of colonial domination always disrupts [in spectacular fashion] the cultural life of a conquered people. This is made possible by the laws/rules introduced by the occupying power. However; as colonial empires collapse the contradictions in the colonial system strengthen and maintain the peoples will to fight while promoting and giving support to national consciousness. This article is going to look at how Izithunywa Zohlanga (Messengers of the Nation) use indigenous repertoire and idioms to produce music and literature that speaks directly to the present in post-Apartheid South Africa while at the same time being custodians of our heritage through performances.

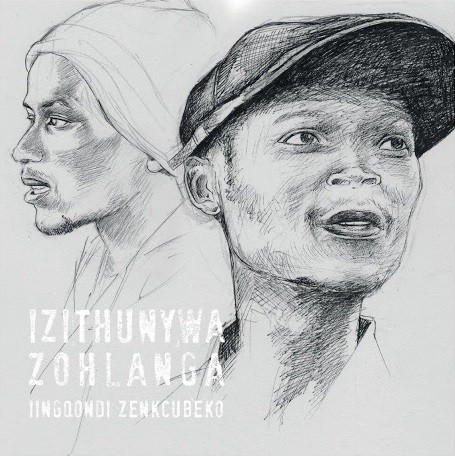

Liyo and Pura are Izithunywa Zohlanga; a duo that comes out of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. The two grew up together and went to school together in Port St. Johns and East London. As kids they used to mime rappers like Snoop Doggy Dog, 2 Pac, Busta Rhymes and others during school functions. Around 1993, they started looping beats with cassette decks. After matric they both attended Cape Audio College in Cape Town.

Liyo and Pura are Izithunywa Zohlanga; a duo that comes out of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. The two grew up together and went to school together in Port St. Johns and East London. As kids they used to mime rappers like Snoop Doggy Dog, 2 Pac, Busta Rhymes and others during school functions. Around 1993, they started looping beats with cassette decks. After matric they both attended Cape Audio College in Cape Town.

They then enrolled at The University of Fort Hare to study African Music and Literature. These brought them a broader insight in linguistics/literary skills, traditional song/rhythm, and contextual/conceptual approach. They were the two of the five founding members of the Afro-fusion band Udaba (Matters), together with jazz musicians Indwe and Sakhile Moleshe, and historian/linguist Sibusiso Mnyanda where they were merging traditional instruments such as uHadi, uMqube, uMqanghi and iKatara with modern instruments fusing sounds of the past, the present and the future. During this period Udaba worked with well-seasoned musicians such as the veteran of Xhosa folklore Madosini, Lwanda Gogwana, Ayanda Sikade, Shane Cooper, Wakhile Xhalisa, Vuyo Khatsha, Texito Langa, and the legendary poet Kgafela oa Mogogodi.

According to Fanon, in the beginning of the occupation the artist produces work [to be read] exclusively by the oppressor, whether with the intention of charming him or of denouncing him through ethnical or subjectivist means, as colonial empires collapse the artist takes on the habit of addressing his own people. Even though Izithunywa Zohlanga recites in Xhosa, they deal with universal concepts, whether they are political, social or economic. On another level, as Fanon continues, the oral traditions – stories and songs of the people – which were put away as set pieces now begin to change.

“The storytellers who used to relate inert episodes now bring them alive and introduce into them modifications which are increasingly fundamental. There is a tendency to bring conflicts up to date and to modernise the kinds of struggle which the stories evoke (Fanon, 1959).”

It is in this way that Izithunywa Zohlanga’s music takes on a Pan-African stance where through it they try to bring together Africans from different backgrounds. Their art might be called, what Fanon calls “the art of combat.” Their music stays relevant because they deal with everyday issues like substance abuse, violence against women and the struggle of students for equitable education. Izithunywa Zohlanga’s art is the art of combat because it assumes responsibility, and because it is the will to liberty expressed in terms of time and space.

The experience that the duo gained from working with all those seasoned artists resulted in them engaging in a scholarly movement along with their contemporaries. This influence soon led to both individuals establishing themselves as independent artists as Liyo set himself on a journey as the musical director of the sensational uMthwakazi band, while Pura became the African prose master in his live project Funda uMyalezo (Learn the Message). Both these works led to these artists becoming activists, engaging in various skills development programs in townships and villages educating the youth in culture and music.

Fanon also argues that the contact of the people with the new movement makes the artist come up with a new rhythm of life and to [forgotten muscular tensions, develops the imagination]. Every time the artist adds new styles to their work the artist relates a fresh episode to his public, which will result in the people asking new questions or even the old ones anew. The idiom used by the duo is mostly inspired by Xhosa literature more than street lingo. As Pura puts it, “[They] just did not want to dilute the pureness of the language.” They even collaborated with a Tswana Hip-Hop group called Retsamaya Legae (We Walk Our Homeland) from Pretoria, Gauteng, to suggest that this is not just a Xhosa movement but an African one.

Storytelling according to the duo is a way of preserving culture. Their music tries to balance between oral tradition and literature. Similarly, the use of traditional instruments and sounds is an “attempt” to preserve heritage. Even though there is a restricted circulation of relevant information in post-apartheid South Africa, it is through live performances that they share their music with the public. They have also published an anthology called Umculo Buciko – the phrase – directly translates to oratory music, and even though they invented it specifically for their sound there have been other artists in the Eastern Cape who identify with it. It became a sub-genre of Hip-Hop similar to Motswako and Spaza. Their first album Iiqgondi Zencubeko (Traditional Intellectuals) shows that they have taken direction of not just being artists but also being teachers and custodians of culture.

These show that as Fanon elaborates, as the new movement gives rise to a new rhythm of life, the existence of a new type of artist is revealed to the public. “The present is no longer turned in upon itself but spread out for all to see.” The artist once more takes charge of their imagination. They introduce new ideas and patterns into their work of art.

Izithunywa Zohlanga not only use traditional repertoire and idioms to preserve heritage and be custodians of culture but produce art that makes critical statements about what is happening in the present. Their knowledge of Xhosa proverbs, metaphors, rhythms and the influence of black-centred ideologies influence their radical original style of music which makes them produce the “art of combat.”

Reading List

Bellio, Ellinore. ‘The Anti-Art of Kongofuturism.’ Land and Homeland. Chimurenga Chronic, (April 2013): 38-39

Fanon, Frantz. 1959. ‘Reciprocal Bases of National Culture and the Fight for Freedom.’ Botsotso, 17 (2016): 228-238.

Hutchings, Shabaka. ‘The Way I See It, We Need New Myths.’ The Fiction of International Law. Chimurenga Chronic, (April 2016): 2.

Ipadeola, Ayatande. ‘Poema: The Art of the Talking Drum.’ Land and Homeland. Chimurenga Chronic, (April 2013): 43.

Sekyiamah, Nana Dakoa. ‘Gospel Christian Porn Rap.’ The Philanthropic Complex. Chimurenga Chronic, (August 2013): 34-35.

For issues of the Chimurenga Chronic – a publication borne out of an urgent need to write our world differently, to begin asking new questions, or even the old ones anew – head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.