words by MADEYOULOOK

photography by SANTU MOFOKENG

The train – igado, isithimela – a means of transport that has become a stand-in for the distances between peoples, the construction of segregation and a mode of economic repression. Somewhere between station and tracks, departure point and destination are the memories and futures of ordinary lives. Spanning the paradoxical gap between Johannesburg city and its neighbour Soweto, run two railway routes made purely for transporting mass labour – a necessity to apartheid planning and ensuring cheap access and continued apartness. Today, the same routes exist, still unable to reach many of the further corners of Soweto, still maintaining a system of labour for the majority and mass capital accumulation for the minority.

But some things have changed and the ways in which the public are able to engage, challenge and occupy their spaces have taken on new forms. Cognisant of this, we met with the photographer Santu Mofokeng to establish the point of crossroads, where things are in motion and where things remain still. To do so, we considered two works of art that explored the practice of train preaching on Metro Rail’s Soweto route – artworks separated by 24 years, medium, intention and democracy.

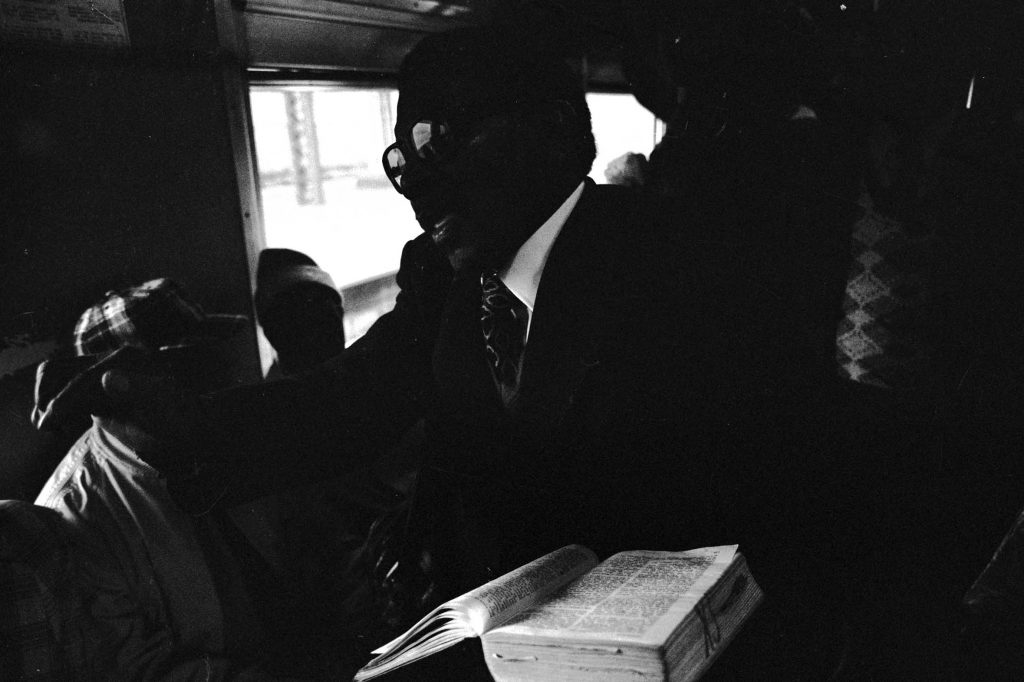

Santu Mofokeng’s Train Church was embarked upon in 1986. A personal project, taken on in response to the overload of violent and blandly political imagery coming out of South African documentary photography. Mofokeng’s project was strongly situated in his own daily experiences and a need to reflect them.

MADEYOULOOK began Sermon on the Train in 2009, a project that looked to push notions of public ownership, interaction and academia into a new direction by facilitating university lectures on the train to Soweto. This project was not based on ordinary life but rather on curiosity – at human interaction and access to knowledge.

And in ’86 I was young at the time so you can imagine Mondays you come with babalas. You arrive on Monday, you just went to sleep at two in the morning, you have been jolling, you hoping when you arrive in the train you can get some sleep […]Two stations down the church begins and people start clapping hands and the bells and sing hymns and then you find yourself in church. – interview with Santu Mofokeng, July 2010

Mofokeng’s Train Church depicts the ordinary occurrence of train preaching on his route to work everyday. The photographs are black and white, largely taken in close-up, intimate and unapologetic. They capture worship, preaching and prayer, faith and passion – all in a days travel. By depicting the everyday, the ordinary and the real Mofokeng sought to do something quite against the status quo – to depict black people not as victims, as sufferers or as revolutionaries, but rather as the faithful and the coping. These were personas of the black South African not captured much since the heyday of Drum. Today, looking at the photographs, they are clearly fraught with strategies of survival. A reality of the train world wide.

The project I decided to do as my own personal project, looking at life, township life, which means if I am photographing in a shebeen its because I am there, if I am photographing football it’s because I am there. These are the kinds of things I do. By inclination. Not because I can’t. I don’t like the kind of work where you show up people, you say Afrikaners are like this, people are like that. I am not persuaded.

Train church was a kind of revenge, these people who were depriving me of sleep. It’s photogenic, and most of the pictures were made in winter, it’s very dark in the morning, gets dark very early. At the time, I did train church on the path I was doing and in time you realise that commuting is not something that’s naturally… it did not come about organically. People were moved from the city so they commute. – SM, 2010

The coming of the railroad is a world-wide phenomenon, directly related to the coming of mechanisation, of new levels of production, of a different kind of labour consumption –essentially with the coming of the modern. All over the world, and particularly in England, the United States, Kenya, India and South Africa, a common history of a network of gashes in the landscape and the blood that oozed from the workers who made them, correlates with the coming of the steam locomotive and its robbing the earth of coal, diamonds, gold, man, woman and child. The South African migrant labour system, the Bantustans, the townships were dependent on the railway and its ability to separate and then connect people when necessary. Still a marker between neighbourhoods, races and classes worldwide, the train speaks of rigid fixities of historical lack for some and excess for others, while embodying in its existence the very nature of movement.

And now suddenly the tenure is for millenarianism, that is to say that life after, in heaven, whatever the Boers are doing to us they will get their come-uppance. 1000 years, whatever, it’s in the Bible somewhere. Kids are becoming priests, because if you are touched or you can see or whatever, these kind of churches, charismatic, big churches, people turn towards looking at ancestors, they turn to the Bible, they turn to look at whatever, because politics: basically were beaten. – SM, 2010

Today the train is the cheapest mode of transport in Johannesburg and its surrounds, and it is synonymous with the working class and the poor. Not so long ago the trains were too dangerous for anyone who had a choice, the violence peaking a number of years ago during a protracted strike by security guards. Guards who chose to risk their lives to go to work were often thrown from the trains – an echo of the pre-1994 violence attributed to the conflict between the Inkatha Freedom Party and the African National Congress.

Trains in Johannesburg today, however, are heavily populated with young and old. Children whose massive backpacks reach their knees hop on and off to school and back without the slightest insecurity. Small-scale entrepreneurs walk from coach to coach with overloaded shopping baskets of absolutely everything you need – nail clippers, zambuk, chappies, superglue, buttons, jiggies, ‘ice’, fruits and vegetables. Every now and again there might be a performance, drums, dancing, ibeshu and all – an astounding display of agility and balance because trains don’t ride smooth.

And then of course there is church. Depending on whom you are, or how bad a day you are having, the train church is either a blessing or a curse. You don’t always know there is one on the coach you get on and two young men might leap onto your coach, Bibles in hands, a station or two after you get on. Sometimes the train is too full for you to move to somewhere quieter. There might be singing, other people in the train might take part, preaching might take the form of an elongated relay of pacing and ‘amen, hallelujahs’ till you get to your destination. Whatever way, church goes on. The loud clacking on tracks and screeching breaks just heightens the fervour, the long day that’s almost past only strengthens the resolve and deepens the melody. If the train is full enough, you can clap without worrying about losing your balance.

Because I don’t have this courage to confront violence or violent situations, even a car accident, I can’t bring myself to photograph that. I decided, when people were saying they will take photographs of, do a project on farm labour or pensioners or whatever, to show African society as victims. I was never into victimology – I decided to do a project that is kind of a fictional biography or metaphorical biography, about looking at my life without necessarily … to try and show what life is like in the township, for me. I go to shebeens, I play football, not necessarily as a kind of lack but to show it for what it is. Not to say we don’t have swimming pools, not to say we don’t have, not in the negative, just by looking at life as it is found in the township. – SM, 2010

The train, its penchant for stirring nostalgia, has not lost its torn soul. It remains a vehicle for moving mass labour. Train churches are set deeply within this reality – part way to pass the time, part negotiator of community, part call of salvation. It is this nature of ordinariness that Mofokeng sought to capture and that we were inspired by.

Sermon on the Train, a lecture series on the Metro Rail, took as its point of departure the ordinariness of train preaching, of sharing enlightenment, of communal understanding and its position slap bang in the centre of isolation. The lectures were given by academics, about academic subjects, to a mixture of usual commuters and an added ‘not so usual’ public. These lectures were intended to ‘take knowledge to the people’, not because ‘the people needed it’ but because those who produced it did – as a way of calling to account the isolation of academia and encouraging the exploration of possibilities for new ways of making and sharing knowledge. Sermon on the Train took on the fraught clash of connectedness and separation that is embodied in the train, engaged it, did not change it, did not make it better but ensured it was taken notice of.

Talking with Mofokeng about the spaces in which our works might find a cross-road first exasperated the separation. Train Church was photographed just as we were born and is deeply situated in historical narrative; Sermon on the Train takes on the current and the colloquial, somewhat naively. Train Church, and Mofokeng in particular, exemplifies classic use of a classic medium, while Sermon on the Train denies conventional forms of art making and definitions of artists. Train Church explores the realities of the lives of it subjects, made initially as document, while Sermon on the Train brings together two extreme opposites, motivated by abstract concept and ‘art’.

Yet Mofokeng’s description of his work, how and why he makes it, brought about some starkly clear motivations for why we do what we do and the power of the ordinary, the strength of normal people and the need to recognise this. Our discussion brought to the fore a number of parallels: the challenge to the status quo, the appreciation of ‘what’s there, everyday’ and the need to take on the cleavages and vast social distances that exist, still.

This article first appeared in African Cities Reader II: Mobilities & Fixtures (May 2011), and is available for purchase at our online shop.