Spearman… Lance Spearman – the name synonymous with the intrepid hero of the photo-comic staple, African Film, started by the publisher of South Africa’s Drum Magazine, produced by fledgling writers and read voraciously by 1970s Nigerian schoolboys, including Uzor Maxim Uzoatu, who dreamed of wars and victories other than those around them.

The Biafra War had just ended in January 1970, but at the age of nine I felt none of the general despondency that gripped the country. All I could think about was war and heroism. So much so that I fabricated fibs to my credulous mates of how, in the company of some diehard Biafran war commanders, I had brought down enemy Nigerian planes from the sky with the aid of a special magnet called Magnetor.

It was against the background of lapping up heroes in the post-war broken city of Onitsha that I came into the unforgettable company of Lance Spearman. I met Spearman through a dog-eared copy of the photo-magazine African Film, given to me by Jude Akudinobi, who was then a secondary school student at Christ the King College, Onitsha, where his father taught alongside my uncle, the linguist J.O. Aginam. Shortly after seducing me into the arresting world of Lance Spearman, alias Spear, the selfsame Jude took me with four of his younger brothers to Chanrai Supermarket and asked us to pick any novel of our choice. Remarkably, I chose a book, The Good, The Bad, The Ugly, without any knowledge whatsoever of the classic Western movie starring Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef. The daredevilry of the novel’s toughie, Desperado Tuco, became aligned to the intrepidity of Spear in my imagination and came to define my growing-up years.

It nearly led to a tragedy. One of the local Onitsha boys who could not bear my hyperactivity brought a friend of his to fight me. The entire neighbourhood gathered to watch. It took no time at all for me to floor the boy, using him to “stone the ground” as we used to say. The boy passed out, and the fellow who had brought the floored fighter was now accusing me of killing the lad, saying, “Have you seen what you have done to him?” It took some heart-stopping moments for the boy to be revived. Reality invaded my fantasy world and the threat of a stint in jail or even the hangman’s noose effectively marked the end of my brief career as the local Lance Spearman. Witnesses of the incident still rib me about it to this day, especially Jude Akudinobi who, perhaps unsurprisingly considering his love for African Film, would take a doctorate in film studies, and now lectures at the University of Southern California at Santa Barbara.

In the heady days after the Nigerian Civil War the look-read photo-magazine African Film starring the dapper Lance Spearman was our hebdomadal staple in Onitsha, the overpopulated township that earned its mark in the world of letters on account of the market literature available there. Some Monday for sure, as Nadine Gordimer would put it, the paterfamilias of the Akudinobi family shelled out one shilling for a copy of African Film magazine, and another shilling for Boom magazine starring the Tarzanlike Fearless Fang. Scores of us had to make do with each edition of the magazines until finally the wear and tear triumphed over our reading.

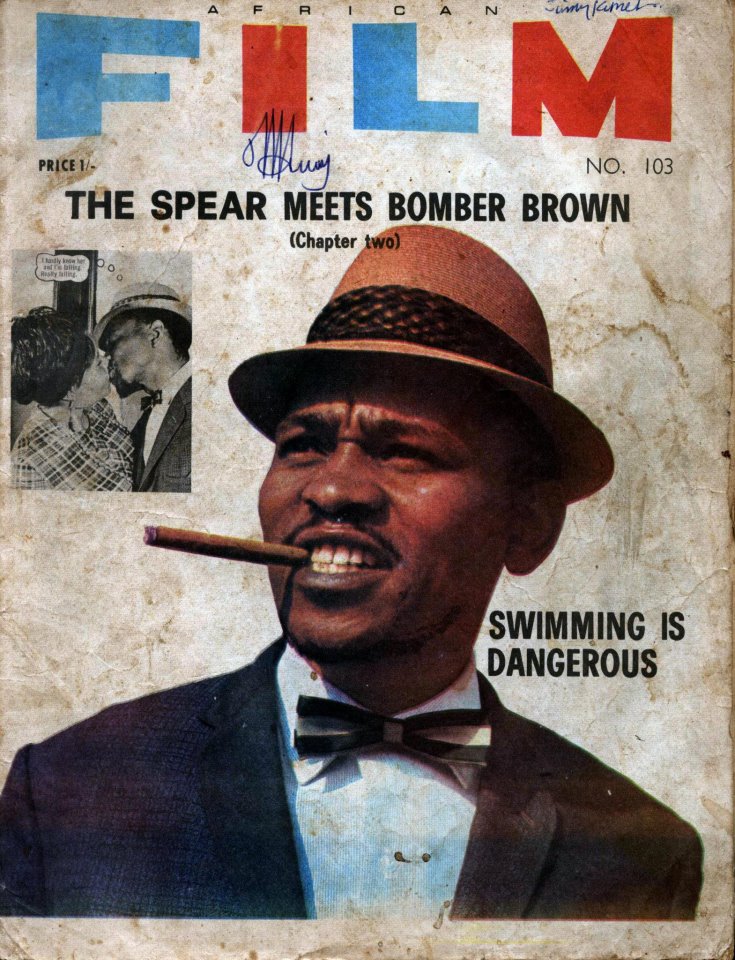

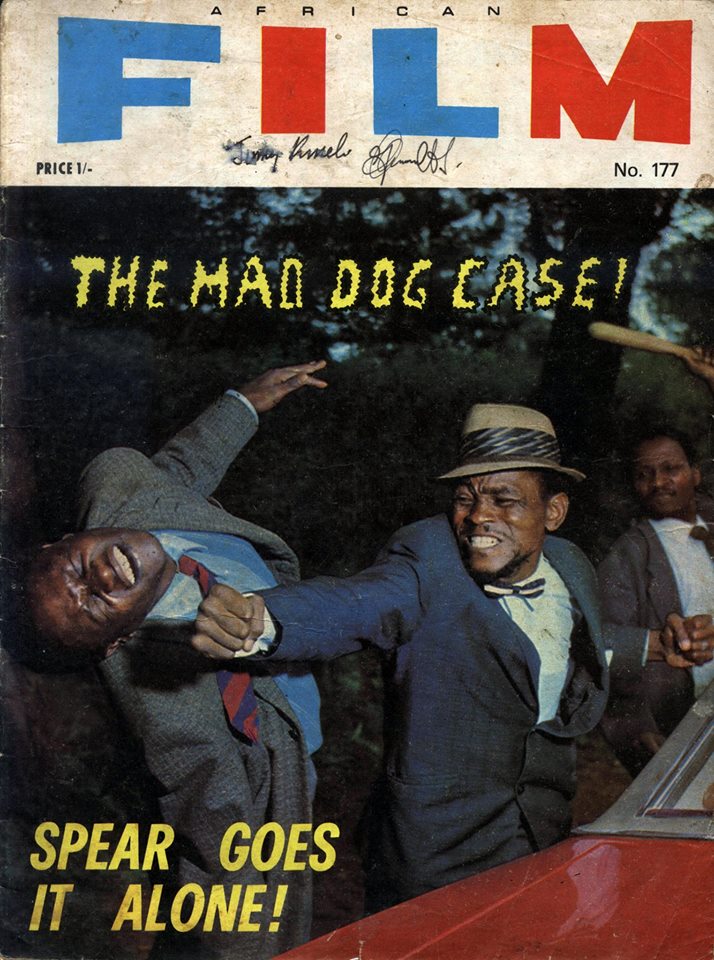

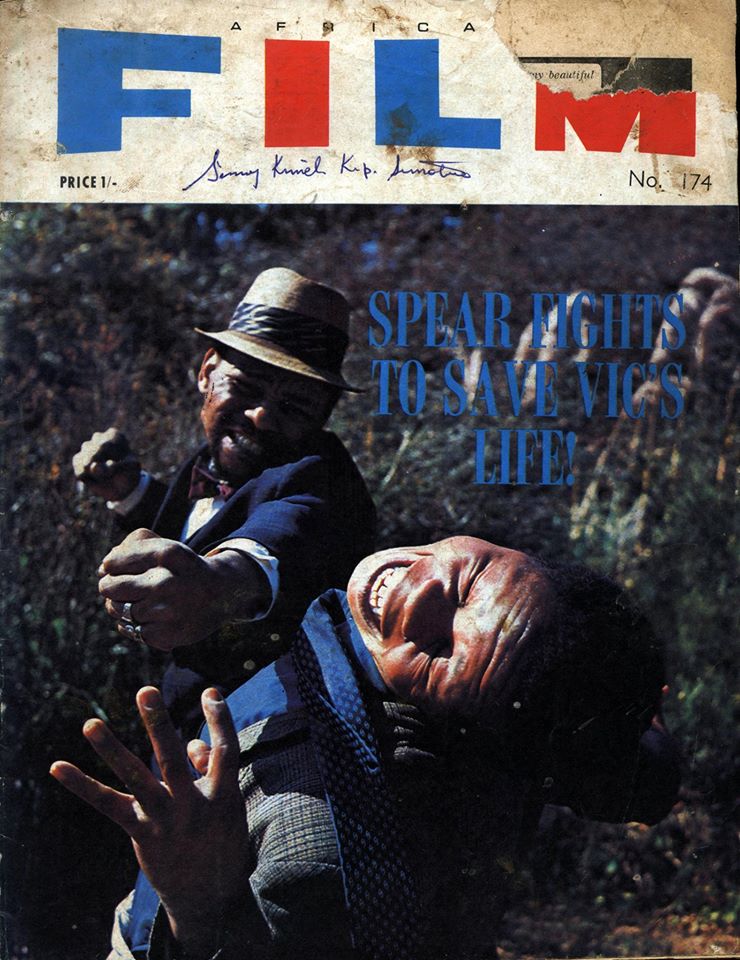

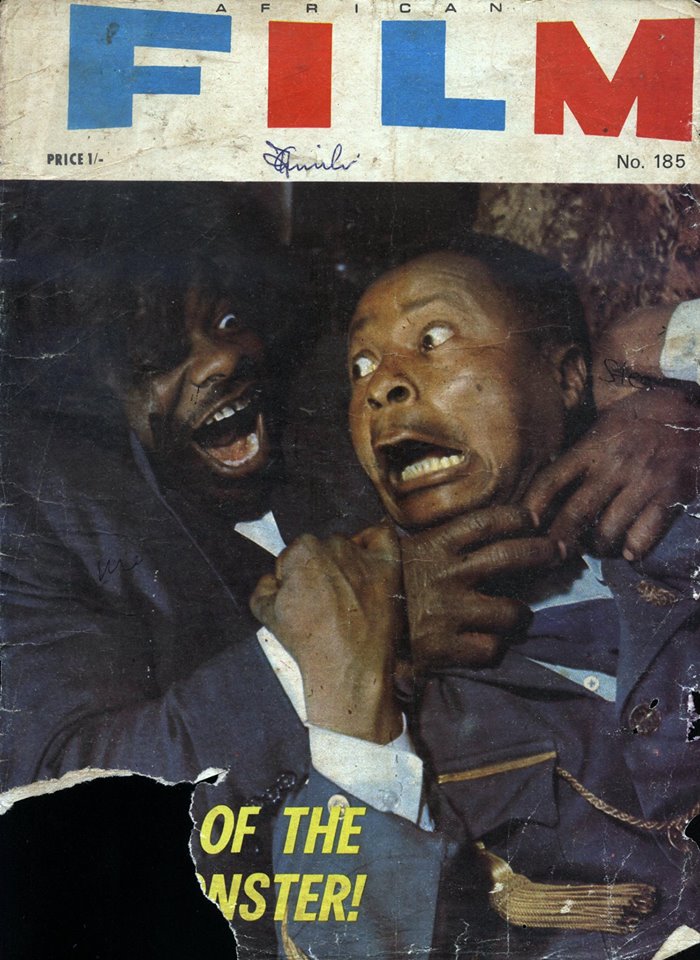

Spear was our darling crimebuster par excellence, a cigar-chomping champion who was a serial lady-killer in the mould of James Bond 007. Riding in his Stingray coupé with his trademark Panama hat on his head, Spear showcased the urbane and the modern. Talking through his walkie-talkie and drinking scotch-on-the-rocks, Spear was indeed the toast of the generation. The breathtaking car chases were grist to the Spear mill that kept us hooked for weeks on end. The modernity of technology added cubits to the appeal of Spear as the role model of the new age of ultra-modern architecture, sharp women and sharper criminality in Nigeria.

Given the anti-apartheid politics of the era, no mention was made that the magazine originated in South Africa. A Lagos- Nigeria address was on hand as the place of publication. It was only much later that I learnt that African Film was originally produced out of South Africa by the legendary publisher of the influential Drum Magazine, Jim Bailey. In the manner that Drum offered fledging writers, such as South Africa’s Can Themba, Nat Nakasa and Nigeria’s Nelson Ottah their break in magazine writing, African Film provided work for about 25 writers, some of whom were students of the University of Lesotho. Initial photo shoots were undertaken in Swaziland, and the strips were then sent to London for mastering before their eventual transnational distribution all over Africa. In the end the publishers had to settle for printing by local subsidiaries. The leading man who starred as Lance Spearman was a fellow named Jore Mkwanazi, a former houseboy doubling as a nightclub piano player, who had been discovered by the white photographer Stanley N. Bunn. Spear had for ready company Captain Victor, the police honcho who forever wore his uniform. Spear’s swanky lady assistant, Sonia, was a study in independent womanhood. His young sidekick, Lemmy, lent to the cast a measure of humane and vulnerable precocity not unlike the role of Jim Hawkins among the pirates of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

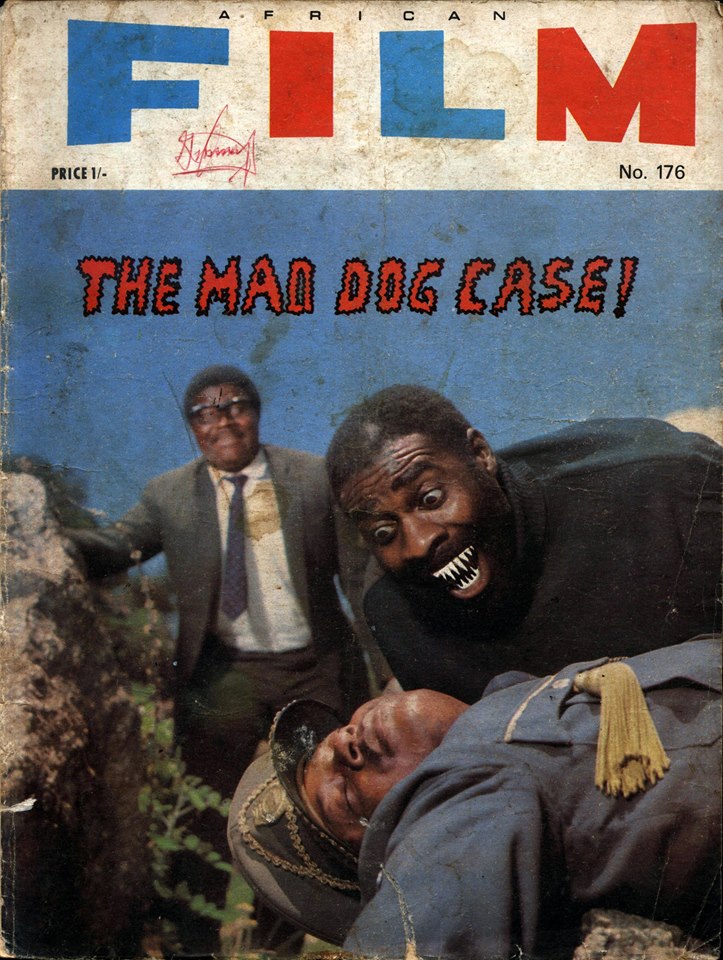

You would always trust Spear to get out of all troubles, given that Captain Victor, Sonia or Lemmy could pull a string or two on their own to stave off the enemy. The dialogue was hip and contemporary, in the manner of the racy thrillers of James Hadley Chase, the hottest writer we cherished back then. The lines were indeed riveting, such that one readily committed them to memory. For instance, the thug bearing down on Sonia gets the following words from Spear as he steps forward for a fight: “Woman-beater, try me for size!” Before the hoodlum can get to the races, Spear lands him the sucker-punch, saying, “You have a glass jaw!” With the fallen thug crying “Aaaaaargh!” Lemmy would congratulate Spear thus: “Attaboy, Spear!” The archetypal antagonist of Lance Spearman was Rabon Zollo, who had lost an eye and thus wore the hideous black eye-patch. Zollo was menace in overdrive. There were other villains like the Hook-Hand Killer who, as the name suggests, killed with the evil hook on his hand. The criminal mastermind was known as Dr Devil. There was Mad Doc with the bespoke serum that had the power to shrink people. Who will ever forget the antics of Professor Thor, who could read the thoughts of people through his vile machine? There was the other professor, Rubens, who used the organs of animals to produce the werewolf. The menace of the Cats almost overwhelmed Spear; it was quite daunting doing battle with cat burglars in black masks and claw gloves that could climb and scale all heights. Hilda “the Head Huntress” was yet another villain who left a mark on the adventures of Lance Spearman. It was the thrill of a lifetime to savour the spells of Spear’s confrontations with diabolical insurance agents, sinister diamond thieves and baleful power syndicates. The cosmic, end-of-the-world wars of Lance Spearman reverberated and resonated with us in an increasingly corrupt post-war Nigeria. Spear offered hope. He stood as the positive force that could save humankind.

Then hope vanished suddenly. It was in the course of 1972 that the supply of African Film stopped, for no reason whatsoever. We were not abreast of the high-wire politics of apartheid, the Cold War and suchlike. The rumours flew fast and free that Lance Spearman had died. We couldn’t believe that Spear could ever die, for as all Nigerians know, “Actor no dey die!” We had to make do with smuggled back issues of African Film dating to the years of the Nigeria-Biafra War. We devoured the back issues, waiting for the inevitable day when the unbeatable Lance Spearman would make a triumphant return.

We are still waiting. We have yet to see the return of Spear, of hope, of the final triumph of good, but the memory lingers of the dynamic action scenes, the assorted camera angles and the ever suggestive sex acts. Black like all of us, Spear served up a counter to white images of heroes such as Superman. In the age of the so-called Blaxploitation films featuring Richard Roundtree as John Shaft and the former American football player turned film star Jim Brown, who beat the living daylights out of white folks, Spear was akin to the local boy who made good, an exemplar of the middle class youth culture of the race. A potent symbol of a possible future for Nigeria – still within grasp, but forever illusive.

This article first appeared in Chimurenga Chronic: Graphic Stories (July 2014), an issue focused on graphic stories; comic journalism. Blending illustrations, photography, written analysis, infographics, interviews, letters and more, visual narratives speak of everyday complexities in the Africa in which we live.