by Nancy Rose Hunt

Beginning nearly fifty years ago, in 1968, Kinshasa has seen an explosion of underground street comics and the man regarded as the master of this form is the self-proclaimed Emperor and Majesty, Papa Mfumu’eto the First. From 1990 to the early 2000s, Papa Mfumu’eto produced over 200 comics, in 115 separate titles, with some series comprising up to 40 instalments, and nearly all of them have been in Lingala, the vernacular of Kinshasa’s streets.

Papa Mfumu’eto first rose to fame with his comic about a cannibalistic urban dandy. This big man transformed himself into a predatory boa in his bedroom to consume his sexual prey: a young woman who unwillingly accepted his invitation home. A sequel playfully engaged with Papa Mfumu’eto’s own sudden popularity in Kinshasa, with depictions of his readers eagerly buying Super-choc no. 2 to learn whether the boa-man is fact or fiction. True he was, they soon learned, as the snake-man vomited up his meal of a woman as cash. Dollar bills by the hundreds filled the big man’s bedroom, while shocked Kinois readers, shown in the final frames, stayed glued to the unfolding news.

Readers interpreted this snake-like figure spewing out dollars to be Mobutu, the head of state, long rumoured to combine money, women, and sorcery with power.

These were common terms in Kinshasa’s vernacular – ingestion and expulsion, power and eating, wealth and malevolence. Idioms about the abuse of power were salient during the last moneymad Mobutu years, as rumours swirled about his use of poisons and other nefarious technologies to eliminate enemies and keep his grip on power.

Over the years, Papa Mfumu’eto has captivated diverse audiences with a varied output about the everyday and spectacular in Kinshasa. His comic booklets tell of the visible and invisible, of ancestors, spirits, and of scary creatures acting upon lives in decisive, mystical ways. His trajectory of fame is part of his narration. He often talks and writes about himself in the third person, portraying himself as a special, fantastic hero, and referring to himself as the First or “your much beloved” when addressing fans.

Irony, too, is everywhere in Papa Mfumu’eto’s comics, manifesting in strange, mixed-up, animalhuman creatures clutching deadly technological objects. His hierarchies are subtle and everyday, moving between well-dressed bigmen, famous musicians, a ruthless head of state, and ordinary women and children.

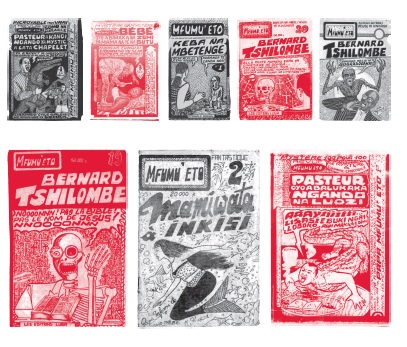

Papa Mfumu’eto’s prolific production has continued into the 2000s when he has begun painting as well. But he hasn’t entered the global comic or art circuits, almost wilfully circumventing them to keep his focus on his Lingala-speaking publics in Kinshasa and the Lower Congo region. His print technology remains simple and monochrome (except for covers in bright colours).

His output is almost miraculous, given the difficulties of sustaining production, but he has never sought an audience in more lucrative markets elsewhere. He remains true to his readers, captivating them with stories drawn from the reality of their everyday existence.

His comics have long contained an impulse toward diagnosing medical, social, and spiritual problems. He likes to intervene with a guardian touch, extending moral messages about domestic and sexual lives to his readers, often through eerie stories that produce laughter and unease. He represents adultery as an occasion when occult forces intervene. In Likambo ya Ngaba, for instance, during a clandestine visit to a hotel for sex, a woman becomes fastened to her partner by a machine with a lock device.

Permeability between life and death is another recurring theme and it’s at the heart of his longestrunning series, Tshilombe Bernard, about a character oscillating between life and death. The series lasted three years, 20 issues in all, with the hypermodern subject dressed in suit and tie flickering between living and dying, while the pages filled with caskets, graveyards, fancy clothes, and other signs of life, death, and fame. Mwasi ya Tata shows continual misunderstandings between a small boy and the wife of his father. The theme of a child caught between a parent and a new lover or spouse appeared again in his famous series, Muan’a Mbanda, about children growing up in a household of cowives, at risk of rivalry and its results: hate, hunger, and revulsion. Papa Mfumu’eto’s comics about children have always had a strangeness to them. In one, a baby born in the night merges with her old grandmother into a new being that possesses a young wife, Nzumba. Soon this spouse and her husband are beset by calamities and disorders, while not realising the mysterious baby is the responsible, poisonous agent.

While his style has varied over the years, Papa Mfumu’eto’s comics all include strong images and striking covers. His texts are carefully rendered and sometimes excessively detailed, the tiny words often filling an entire page. His innovative layouts produce the surprising tempo of his plots, whether in a single booklet or across a series. Household troubles and national grief, whether rooted in sorcery invasions, sexual rivalries, or human animosities, combine with wondrous flashes of celebrity and power. Through all of it the selfproclaimed Emperor and Majesty chronicles life in Kinshasa: past, present and future.

This article first appeared in Chimurenga Chronic: The Corpse Exhibition & Older Graphic Stories (August 2016)