Achal Prabhala goes to the heart of the Free State literary renaissance with the “deliberately mysterious and prodigiously talented” Omoseye Bolaji.

The literati in Bloemfontein are a rapidly expanding tribe and their body of work is not merely a pile of books. Instead, it is a pervasive social phenomenon that is testament to the power of belief. Like the best kind of phenomena, “Free State writing” is not make-believe so much as made by belief. There has always been a kernel of truth to it, and yet, the significance of the phenomenon is the lure of a rumour of a whole peach around the kernel − a lure so attractive that there is now a fat juicy peach there.

The city boasts a full-fledged scene, complete with writers and critics and patrons, towering egos, quivering readers, and a whole lot of shadow-boxing. At the centre of this scene is a group of key people − the buccaneering storyteller, the trenchant critic, the organiser, and the buyer of books. At the heart of this centre is a deliberately mysterious and prodigiously talented 40-year-old Nigerian émigré called Omoseye Bolaji.

On a recent Thursday morning, Bolaji was declining to be interviewed. He was doing this in typically flamboyant style − throwing his hands up in the air, protesting rumours of his importance, flopping down sideways on his worktable, jumping back up, scolding me for not paying attention to the young poets present in the room, and burying his face in his hands − with the effect of making me feel like I had brought news of the death of a close relative. Every now and then the torrent of exclamations would abate, Bolaji would peer through his fingers, and he would get in a cannily intuitive question, like “How did you get the money to come here?” or “Why couldn’t The Chronic send a South African to do the story?”

It took several entreaties for Bolaji to agree to a conversation, and several more for him to part with his phone number and email address. Asking the simplest question, say, “Can I give you a ride back home?” would elicit consternation, a long pause, and then a frank explanation that he lived in several homes at once, none of which he would like me to know about.

For all his reticence, Free State writing is amplified on the internet with hardly any; there are hundreds of websites, fan-sites, blogs and social media feeds that broadcast every move of every writer from the region and Bolaji in particular. Fuelling this online fire is a convincing mix of real and fake identities who engage in real and fake criticism, making the whole conversation seem bigger and richer than it is, thereby bringing more people in, thus leading ultimately − and wonderfully − to a bigger and richer conversation. One could dismiss this hoopla as self-promotion but that would be a mistake; Bolaji and his brigade have no choice but to take themselves seriously in a literary industry that does not.

On the face of it, Bloemfontein is an unlikely location for the South African literary renaissance. There are no obvious indicators as to why the surge should have originated here, notwithstanding the city’s claim on the origins of JRR Tolkien (whose wisp of a memory, “It was a hot country”, appears everywhere), the ANC, and Leon Schuster. (Other notable attractions, according to its official guide, include being the site of the province’s only 24-hour McDonalds.) Bloemfontein falls under the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, which contains some 700,000 people and roughly as many ‘Presidents’, each of whom has a road named after him.

On President Brand Street, in the centre of town, sits the National Afrikaans Literature Museum and Documentation Centre, and it is within these 19th century walls that the odd coupling of an obdurate past and a confident present is first evident. The museum devotes a small room out front to new writing in the Sotho language, and one section of one passage to a pop-up exhibition for the prolific Sotho writer KPD Maphalla. In keeping with its name, the museum is a literary Valhalla, and most of the attention is given over to books, papers and portraits of great Afrikaans writers. The energy inside the building, however, is generated by an altogether younger set of people, speaking an entirely different language, who have commandeered the space in a frictionless takeover that appears to have been welcomed by all.

Bolaji’s story begins some 40 years ago in Ibadan. “Writing has been in my blood all my life,” he says. The decision to write was met with ridicule by his family, despite the fact that they loved and consumed literature. “My brother and sister told me that I will destroy my life. And from a materialistic point of view, I would say they were right.”

At some point in the early 1990s, in London, he came into contact with a literary-minded South African exile called Flaxman Qoopane, who invited him back home − to Bloemfontein. Bolaji’s first stop was Fort Hare, at whose university a distant relative taught chemistry. After a few years there, he moved on to Bloemfontein, where he has lived ever since. “He painted a more rosy picture than the reality I encountered,” he adds wistfully, recalling Qoopane. “The city was nothing like he said it was. Anyway, I suppose there’s no nirvana on this earth.”

After a decade of writing and editing jobs at some of the country’s most popular newspapers, including the Daily Sun, he moved into his present job. “I edit the smallest newspaper in Africa,” is his defiant way of describing it. The newspaper in question is the Free State News, a weekly that is distributed free of cost, where his formal title is News Editor, though his work usually extends beyond his brief.

The Free State News looks and feels like a newspaper from a small West Indian island where nothing ever happens. Like its West Indian counterparts (and solely due to Bolaji’s influence) the newspaper is committed to relaying despatches from intelligentsia, the result being a vivid mix of, say, a review of Hlonipha Mokoena’s book on the making of the Kholwa intellectual juxtaposed between classified advertisements for tractors and pigs and a weekly round-up of the world’s most absurd accidents.

On the life literary, Bolaji is by turns romantic and melancholic. “Literature is not about entertainment. For me, there must be some commitment − and I’m not talking about politics.” The melancholia, a lurking presence in his novels, also seems to be his own. He is given to sounding like John Lefuo, the misanthrope protagonist of his most compelling book, People of the Townships:“Being a black man is sadness itself − unless you don’t give a damn about anyone else.”

By his own admission, he has not earned significant amounts of money from writing. Not expecting to earn from writing has, in turn, given him a kind of freedom. His favourite claim, now endlessly played and replayed in all corners of the internet, is that he writes for the “average man” − the “grassroots”. I ask him if I would qualify, and he waves me aside. “I used to write literary essays,” he says, “but no one understood them. Now, I meet people selling onions on the street who will come up to me and say they read my books in the library, so I don’t know − maybe I should just say I write for illiterate people.”

Although it is true that a lot of people are reading his books, they are not necessarily buying them; the reason they can be read and the reason he can print the books lie elsewhere. New writing from the Free State is an enterprise that relies wholly on self-publishing. Free State writers live and work outside the scope of the traditional publishing industry, and their real breakthroughs are the gumption to recognise that a book is simply a set of words printed on paper, and the brazenness to go out and make one.

One reason Free State writers are read is Qoopane, a cultural impresario and freelance writer, whose contribution to the movement − other than enticing Bolaji to South Africa − is a decade of literary evangelism, conducted from a shed in his backyard that doubles up as a community library.

Qoopane’s acquaintance with books began, appropriately enough, with the apartheid government’s decision to ban them. In the 1970s, one of his first jobs was as a packer in what was then the Orange Free State legislature, and he was assigned the task of storing seized samizdat. In exile, through Lesotho, the UK and the Soviet Union, with the assistance of magazines like Staffrider, his acquaintance with literature grew into love. Now, with a coterie of young writers to assist, Qoopane opens his home in the Bloemanda township to students on a daily basis.

The other reason the books are read is also the reason they can be printed at all. In 2001, Jacomien Schimper became the Director of Library and Archive Services in Free State, a position she still holds. She had worked in the library system all her life. Upon assuming charge of a department that was responsible for stocking all 170 public libraries in the province, she set about making some changes. Her first impulse was to go local. Through early meetings with Qoopane and Bolaji, she realised that the only way to find local books was to create them − which is exactly what she proceeded to do.

The economic considerations facing the Free State writer today are fairly straightforward. For an average-sized book of 100 pages and a print run of 200 copies, basic costs for design, typesetting and printing come to about R10,000 in all, or R50 per book. (Luxuries like better design and printing with a spine are extra.) The author then approaches the public library system with a sample of the book, which is priced for retail at, say, R150. The staff at Library Services evaluate the proposal and, if it passes muster, buy about 100 copies at a discounted price of, say, R100 a book.

From the author’s perspective, an offer of this sort is not only a guarantee of breaking even, but one that leaves aside another 100 books for further sale, besides ensuring the book’s circulation through the province. In a city bereft of pavement booksellers and informal bookshops, in a country where the organised book trade is inaccessible to rogue writers, the support of the public library is a crucial intervention without which there would be no new writing at all.

The scheme is hardly unusual: through the bulk purchase of school textbooks, the government of South Africa is already the publishing industry’s largest customer. And all through the bad old years, Afrikaans publishers in the ‘trade’ sector − popular fiction and non-fiction − effectively received subsidies from the state to make ends meet. What is unusual is that, except for a few attempts in the Northern Cape, other provinces in South Africa have not tried to create a similar writership.

A few days into our meeting, convinced of my bona fides − or just weary from having to dodge me so often − Bolaji begins to relax. “You know how it is. When you are not in your country you can’t be too aggressive − you have to be careful. You may find that you never fulfil your potential otherwise.”

And I begin to understand his public persona; his dogged insistence at calling every teenage poet in town a “superstar”, the convoluted shame wrought by his superior skill, and the mad brand of civility that is completely his own. “That Saint George Vis, he wanted me to help him, and then he threatened to kill me. I don’t think he meant it,” he says, speaking of a fellow writer, and casually adding, “He’s a bit mentally unbalanced, but we are good friends now.”

Even when relaxed, Bolaji is critical through gritted teeth, as though he cannot fully bring himself to name bad writing. He leaves that to Pule Lechesa, a critic who has no such problem. Lechesa is a journalist and writer in his own right, and the Sotho translator of Bolaji’s only published play, The Subtle Transgressor, staged as Joo, Letla Shwa-Letla Botswa in Ladybrand. He is also the man who keeps literature from Free State honest, by tearing into any budding writer who dares assume that being black is a sufficient and remarkable condition for art − an unenviable responsibility, given the proximity of those involved.

It was Lechesa who first pointed out the parallels between the Bloemfontein boom of today and the pamphlet literature that circulated in the markets of Onitsha in the 1950s and 1960s, a literature that died out exactly at the time Bolaji was born. While Bolaji’s self-professed mentors are the high priests of international pulp fiction − James Hadley Chase, Sidney Sheldon, and Peter Cheyney − his closest parallel, in fact, lies nearer home, in the form of a former Onitsha pamphleteer whose trajectory he deserves to inherit. Fifty years ago, Cyprian Ekwensi was the breakout star of the Onitsha market movement, a writer rooted in the vernacular and simultaneously propelled out of it by sheer talent − a lot like Bolaji, the Bard of Bloemfontein, whose delicate prose escapes the cage of the interesting phenomenon.

For now, there is the small matter of stage-fright to get over. Bolaji doesn’t like public speaking, won’t go to book launches, and has not attended a single literary festival. “I’m shy,” is all he offers by way of explanation. After having tried and failed to interest a mainstream publisher in his work, he appears to be relieved not to have to deal with the politics that big success can bring. Or, at least, he has convinced himself that he is.

“I’m too sensitive for all that,” he says, averting his eyes from me, and looking out at nothing in particular. “I prefer my own life.”

In commemoration of our 20th year, we will be digging through our extensive archive.

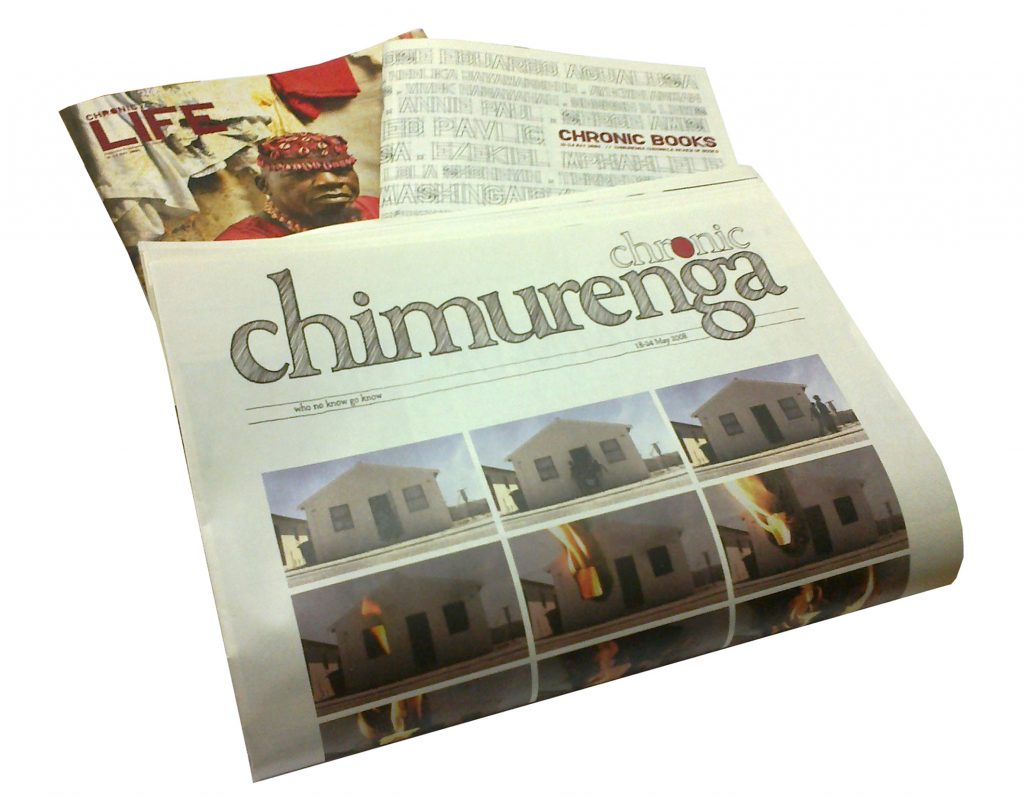

This story, and others, features in The Chimurenga Chronicle, a once-off edition of an imaginary newspaper which is also issue 16 of Chimurenga Magazine. Set in the week 18-24 May 2008, the Chronic imagines the newspaper as producer of time – a time-machine.

To purchase as a PDF, head to our online shop.