By Dominique Malaquais

The problem with museums

The term ‘architecture’ has historically been defined by and in relation to Europe. The same is true of the word ‘museum’. Both are understood to reference permanent structures created by highly trained specialists, according to set rules, for use to specific ends. This definition is exceedingly narrow. It excludes the overwhelming majority of structures encountered, historically and today, in Africa, Asia, Native North, Central and South America and sidelines virtually every exhibition arena worldwide that is not based on an ‘Occidental’ understanding of art and its appreciation. This is no serendipity: architecture generally speaking and museums in particular have played key roles in the construction of ‘first world’ political, economic and cultural hegemonies; such hegemonies, by definition, are the stuff of exclusion. The American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Musée des Arts Premiers (Paris’ latest ‘Africanist’ endeavour, now known as ‘Musée du Quai Branly’ to downplay ‘Premiers’, which – whatever they say – means ‘Primitive’) are considered ‘great’ as buildings and exhibition spaces; the spaces that were variously looted and destroyed to procure the objects they contain – Kwakiutl potlatch lodges, Batak longhouses, Senufo Sandogo shrines – are granted neither distinction. When they are appreciated, this tends to be in a retrospective manner – a celebration of things past, in need of commemoration and (where such is still possible) conservation. Ephemeral spaces, wherein much art outside Europe and the U.S. has historically been displayed – performance arenas, initiation clearings, temporary water-born structures, carnival floats – are barely, if at all, taken into consideration.

As a general proposition, this is problematic. In the specific context with which we are concerned, it is a matter that demands urgent redress. Broadly, our goals can be defined as follows. We seek to create a space to showcase art. This space is expected to question and transgress definitional boundaries. ‘Art’, here, will include but not be limited to the visual arts, such as these are defined in most Euro-American settings; works that hang on walls, stand on pedestals and are projected onto screens will be joined by performance pieces, aural experiences and events produced by a direct, physical exchange between works, their creators and their viewers. Viewing, reflection, dialogue and creation will happen simultaneously. ‘Art’, here, will be understood as both process and end product. Wherever possible, it will be a result of interaction; always, it will seek to prompt interchange. We aim, in short, to elaborate a radically new kind of space for experiencing art. The guiding force behind this project is the staging ground for its elaboration: the African continent.

In theory, a space and set of experiences such as we envision could be brought into being anywhere on the planet. In practice, however, Africa is the site and, with this comes unique challenges and opportunities. First among these is the possibility of redefining what art is or is understood to be in a museum setting and what kinds of architectural stage sets might best bring it to life. In order to actualise this possibility, we propose to draw on models for the display and reception of art developed by African practitioners past and present. Our goal in doing so shall be not to emulate or reproduce these models – the point here is not to essentialise, to produce an ‘African’ experience of art (whatever that might be) – but to seek inspiration from these models. Other templates will be explored as well. The majority, in all likelihood, will not be Euro-American. This will be so not in opposition to the world’s Louvres or Guggenheim Bilbaos, or to the exclusion of approaches they might offer, a number of which may prove quite useful: the entity we hope to create is not an answer to or a rebuke of European models. What we propose, rather, is a means, a locus, to explore a vast history and heritage of approaches to the appreciation of art that have gone largely untapped, even by the most forward-thinking ‘Western’ institutions. We envision a laboratory: a site positioned in Africa that looks to Africa and, in broader terms, to the world beyond Europe and contemporary North America, as a point of departure to articulate innovative ways of thinking, doing and feeling art.

How might these ideas translate into – be actualised as – physical space?

Structure and malleability, take one:

Looking from the outside in

If we hold ourselves to classical definitions of what constitutes architecture, we find ourselves, for the most part, before structures that are meant to be unchanging. Once the last hard-hat has left and the final item has been ticked on the architect’s checklist – once the inaugural ribbon has been cut – it is expected that the building will remain as-is. Alterations to its layout or ornamental programme are to be avoided. Where such are made (an extension, a renovation) they are considered exceptional. Typically, the goal is to make them as unobtrusive as possible; more radical approaches (I.M. Pei’s enlargement of the Grand Louvre, abortive plans to rethink Alcatraz as a site for condominiums) are often, initially at least, roundly condemned.

Although they are commonly presented as normative, such conservative ‘takes’ on building structure and form are, in fact, the exception. They are hallmarks of the Euro-American architectural tradition (and, in this context, one might add, have a relatively shallow, post-17th century history). In other parts of the world, at various points in time, very different approaches have been adopted. Adobe structures – common, in a wide variety of forms, from the 7th century Maya city of Palenque to the ports of Djenne and Timbuktu circa 1700 and the present-day Pueblo renaissance in the American Southwest – provide a useful example. In this mode of construction, flexibility of structure and form are foregrounded: they are built into the building process, expected to occur as a result of usage, viewed as an integral part of the building’s life and identity. Put simply, a building is expected to grow and change over time. It is meant to have a life that intersects with, reflects and acts upon the lives of those who bring it into being.

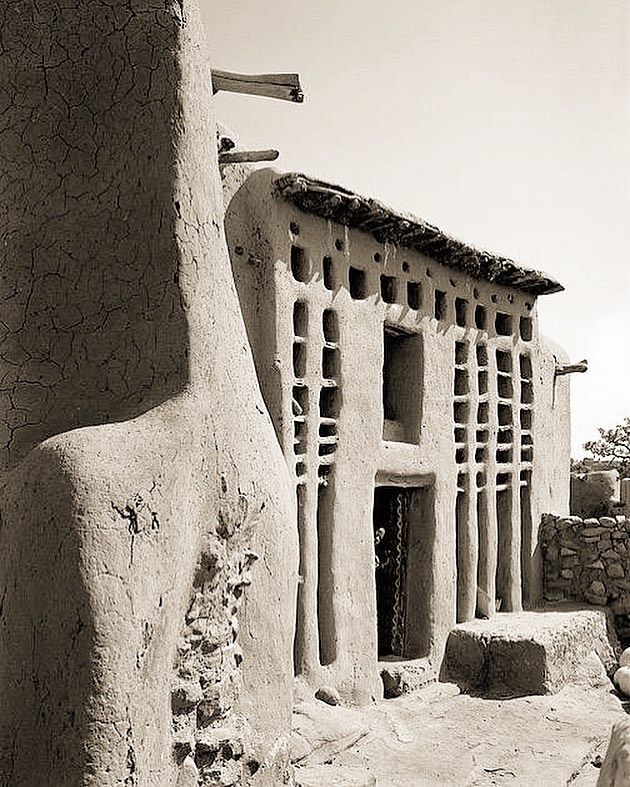

Consider Dogon architecture of south-central Mali. When a ginna house, home to a community leader (or hogon) is first built, its primary characteristic is rectilinearity. It is a quadrangular structure fronted by a grid-like façade divided into an even number of square or rectangular niches (22, 44, 88, depending on the size of the building). After the builders leave the site – when, in a Euro-American context, it would be declared finished – this is when the ginna house begins to live. Within days, an inauguration will be held, which will radically alter its appearance. A thick paste of millet beer and blood drained from sacrificial animals will be poured over the edges of the roof and allowed to run down the façade, creating a play of colours, patterns and meanings. Objects will be placed in the niches, in honour of past members of the community. Such ceremonies will be repeated at set times during the year, each adding a new cluster of layers and significance to the house. Further transformations will result from replastering, a process essential to the structural integrity of the building, which, because it is made of unfired mud, is put at risk by the heavy rains that fall in short but furious bursts once a year. As one replastering follows another, the edifice’s initial rectilinearity will give way to softer, increasingly abstract contours. On the roof as well as in the façade niches, altars will appear, some visible to the untrained eye, others occulted or implied. Altars may appear before the structure as well and, in all likelihood, a shrine (known as binu) will be constructed nearby; it too will undergo incremental, yet significant changes over time. In each of these instances, the transformations effected will have two related dimensions: one of form and one of essence. The driving force, in both cases, will be a substance called nyama – in broad terms, the energy of life. Nyama is essential to and is a by-product of all human activity. Some actions, however, require and produce more nyama than others. Spiritual undertakings, particularly where the spilling of blood is involved, and group endeavours are cases in point. Thus, when a ginna becomes the staging ground for a celebration of persons departed, or when it is replastered, nyama – life – is both harnessed and produced. In the present, the past is honoured and the future made possible. This, it should be noted, is not an approach that concerns architecture alone. Ritual statuary, certain types of masks, ephemeral divination spaces and the landscape itself (notably rock faces and caves) are treated in a similar manner – as forms and loci constantly undergoing change as a result of and in the interest of furthering life.

Dogon Architecture | Ogel Ley, Sanga, Mali

Other examples of approaches to the built environment as a changing entity, transformed by and transformative of life, might be adduced. On the African continent, one might mention, among many others: Bamileke ceremonial structures of Cameroon (mshang), which grow, quite literally, with the status of their owners (the building expands, acquiring increasingly idiosyncratic features, much as a foetus does in a woman’s womb); Tuareg housing compounds of the Sahara and Sahel – movable entities articulated as modular structures that can expand and retract as needed; Mushenge (also known as Nsheeng), the capital of the Kuba kingdom (DRC), which, from the early 1800s to the 1970s was an itinerant city, meant to relocate with the advent of each new monarch; Great Zimbabwe and related sites, which, in all likelihood, in addition to their ceremonial stone cores, incorporated a range of more ephemeral and therefore more malleable structures… In most such edifices and sites, works of aesthetic value, spiritual and personal significance are/were displayed; within and around them, performances occur(ed).

Such sites and structures suggest a range of different ways to think about built form and the articulation of spaces to experience art. Again, what is proposed here is not that specific examples be emulated, but that approaches be devised that look to such models as are briefly referenced here as platforms, as starting points for innovative ways to think about art, its presentation and reception.

Structure and malleability, take two:

In quest of flexible interiors

Of what use might such models be, concretely? One answer arises in response to a key problem faced by museum designers and curators everywhere: the matter of flexibility. How does one create exhibition spaces that allow for the display of such radically different art forms as Cubist painting and Asmat bis poles, Victorian furniture and the nightmarish, late 1990s fun-house installations of Pascale Martine Tayou, which require that the viewer knock noses with used condoms hanging from the ceiling? Essentially, two answers have been offered to date: (1) refusal to contemplate the problem (F.L. Wright, for whom the museum was the work of art itself, to which all other objects and human beings were secondary); (2) creation of spaces rendered reasonably malleable internally by movable walls, ceilings and floors (examples of this approach abound, though entirely too many of the ‘great’ museums have yet to avail themselves of the possibilities they offer). Neither solution is particularly satisfactory. In the end, the works shown are always, to a greater or lesser degree depending on the case, shaped by the building; the structure and form of the edifice define how they are displayed and, accordingly, how they are received. To a certain extent, this is inescapable; Baron Haussman knew it, Foucault has waxed theoretical on the matter: the built environment shapes us and the way we see the world. The relationship between architecture and its human inhabitants need not be, however, and in fact is rarely, a unidirectional phenomenon. Lefèbvre, Certeau, Mbembe make the point masterfully: space can be impacted upon by what it contains, made to live and breathe and change in form and meaning both, in response to the needs of those who interact with it. Dogon ginna houses and Bamileke mshang are the physical incarnationof this argument.

The kinds of experiences we would like to foster cannot exist without reciprocity – or reciprocities, rather – between the viewer, the viewed and the space that brings them together. Under the circumstances, it seems clear that a third alternative to the question of flexibility needs to be explored. This is where our models come in. Why not imagine a permanent site for the display of art that, in its form and meaning, is impermanent, transient? Why not create a site that can morph like a ginna, expand like a shang, be moved altogether and if need be rearticulated in radically different ways, like a Tuareg dwelling or a Kuba capital, equipped with additions and outcrops like a zimbabwe? Such a site would be transformed to accord with the physical and philosophical needs of the art presented and with successive layers of experience brought into the space by viewers, practitioners and staff. Art and site would change in tandem; one would react to and impact on the other, resulting in an alchemy that would itself be altered through use.

What might this look like concretely? The intent is not to create a space that is in all aspects changeable or movable, but one the most visible and most traversed components of which can be radically transformed. How might this work? A complex such as we envision requires a physical plant, storage spaces, restroom facilities, offices and staff quarters. Here, permanent structures are necessary. The first three types of spaces might best be located underground, so as to impact as little as possible on the surrounding landscape. Office and staff areas require space above ground. Here, we might envision low-lying structures, made of materials that, visually and ecologically, allow the buildings to wed the landscape, to become an extension of rather than an imposition on their surroundings. Here, by way of a model, we might valuably look, on the macro level, at the choices made by Dogon architects (drawing on examples from the Bandigara Escarpment, one might consider building the two structures into the hill); on a micro level, another model one could look to is the work of Cameroonian architect Kala Lobé, whose domestic structures are refined exercises in the creation of dwellings that court the senses, yet are economical, environmentally friendly and sustainable.

Some exhibitions may include objects that call for rigorous climate control. For these too, permanent structures would be best. These should echo the office and staff buildings: same materials and scale, similar incorporation into the landscape. Alongside advantages of a purely aesthetic nature, this type of arrangement would participate in the creation of a space that eschews traditional hierarchies, one in which a balance is struck between the art displayed and the people who make its display possible. From a visual standpoint, the arrangement would provide both a staging ground and an anchor for the centrepiece of the complex: its transient heart.

The heart of the complex, in this proposal, would be a wholly temporary structure (or structures). What might this look like and how might it function? In recent years, leaps forward have been made in the manufacture and design of materials for use in the elaboration of temporary, modular structures. The advances have been such that structures of this kind have made their way, either in toto or as inspiration, into the work of key architects. It is now possible not only to erect large, complex and visually pleasing modules of this type, but also to equip them with a number of features necessary to protect people and objects within from heat, cold, rain and wind. In such structures, art can successfully be displayed, performances held, encounters fostered. Alongside these new developments, tried and true methods for the construction of transformable spaces offer a range of historically grounded possibilities that might also be explored; in other words, one need not think only in high-tech terms. Anyone who has bothered to consider the dwellings erected in squatter camps, here in South Africa or anywhere in Western Europe, should be aware that complex solutions to questions of space, the need for expansion, and protection from the vagaries of weather are possible with minimal resources and materials, provided these are tempered by a great deal of experience. (The notion is not to romanticize or elide what are often vicious circumstances, but to underscore the fact that multiple models need consideration here, from a technical and an aesthetic standpoint both; in the latter regard, in relation to less than high-tech spaces, one might profitably look to Zwelethu Mthetwa’s photography of township interiors.)

How it works

It has been suggested that the heart of the complex be radically altered on a regular basis – essentially, with each new infusion of art into the space envisioned. How would this work and who would design each new structure? A concrete example proves helpful here.

Project yourself into the near future. The complex, in this near future, is inaugurating a new season, with a series of interventions centred on the theme of the city. One core idea, or hypothesis, links these thematically-related ‘shows’:

The global city – the city of the future – is not London, Tokyo or New York; it is Lagos, Kinshasa, Douala. The city-to-be is under construction here, now. Globalization, for some, may be financial trades made in real time from a jet zipping from Lisbon to Johannesburg, but on the ground in Hillbrow is where it’s really at. Infinitely more people are living it here, thinking, imagining, implementing it in radically different, heterogeneous, contradictory ways. From their experiences are born forms of cosmopolitanism that, as the 21st century advances, will become the reference points of a majority of the planet’s inhabitants.

Around this core idea, five interlocking shows are planned. Some will intersect, others will happen in parallel with one another, and still others will be staggered in time. To house these shows, an architect has been brought on board. She was chosen based on a competition judged by a panel of architects, engineers, artists and art critics. The brief given to all who entered the competition was to create a series of spaces to welcome the shows and their viewers. Submissions, the applicants were advised, should be crafted in such a manner as to interact with the works to be displayed – paintings, sculptures, installations, performances. All structures proposed should echo, support, question and complicate what viewers will encounter; so too, they should simultaneously energize and challenge viewers, encourage them to look, enjoy, reflect, perhaps even create. The space that the competition winner has devised is a product of ongoing dialogue between the architect and the artists whose work will bring the space to life. Some shows will be curated by the artists themselves, with the technical assistance of an in-house designer; others will be guest-curated. In both instances, design-centred dialogue has played a role in the architect’s process as well.

The space she has created houses one large and two smaller exhibitions. The first is a massive installation piece that brings together the work of five artists based in Douala, known as Cercle Kapsiki. The installation is entitled ‘Dreaming Mumbai’. Video, painting, photography, found objects, sculpture, sound recordings and poetry (voiced and on paper) rub shoulders with a wide range of performance artists. In October, a Douala-based street theatre company named Mabrook is in dialogue with the pieces; daily, they intervene in the installation, partly in response to choreography by the artists, partly on an improvisational basis. On three days in November, bass player extraordinaire Richard Bona wraps the installation in sound. Over the next three months, Cape Town-based performers are invited to intervene in the installation. Twice a month, discussions are organized in and about the Kapsiki work. One brings together young people from a school in the area; the other takes the form of a conversation led by a poet, a critic, a transgender activist.

Adjacent to the Kapsiki show, connected to it thematically and spatially yet distinct, is a smaller show that focuses on digital images of Mumbai by Mumbai-based contemporary photographers. It echoes a second smaller show and space, also linked to the central Kapsiki installation: an ongoing series of readings – by writers, performers reading writers’ texts, video and sound recordings of spoken-word art – all on the subject of the city, mostly (but not exclusively) by African and Indian creators. Chairs, cushions and stools are present, to encourage sitting, lying down, listening, thinking, writing.

In the two small permanent structures provided for objects requiring climate control, there are things to see, hear and feel too. In one is a small travelling show of black and white historical photography curated originally at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, on urban spaces on the Swahili coast; its primary focus is the impact on the city of intersections between the East African coast, the Indian Ocean and the Arab world. In the other is a display of Congolese artist Bylex’s futurist architectural models, projecting Kinshasa into the 22nd century.

One or more of the smaller shows may be replaced by another over the course of the season. A series of video pieces on the urban experience by young African filmmakers may take the place of the Boston photography show and the spoken-word space may be replaced by a series of theatre and/or choreography workshops centred on urban themes of the workshop leaders’ choice.

An artist-in-residence and a research programme enter the picture here too, both linked to the various installations, performances and displays. A scholar – someone from Nigeria writing about Senegalese architects at work in the Arab Emirates, say – has been invited to spend three months in-house, to think and write. She may be asked to give a few talks on her findings and ideas for different types of audiences. Two artists – one from Cape Verde, the other from Johannesburg – both welcomed for six-month residences, could be asked to participate too. Though urban spaces may not be at the heart of either artist’s work – no single, overarching idea should be at work, here, lest serendipity exit the stage – one or both might be asked to lead a workshop, every Sunday for a month, sharing ideas with children responding to the shows.

Formal performances – theatre, music, dance – exploring urban themes might be held outdoors during the summer months. A film series on the city (The Battle of Algiers, Blade Runner, Tableau Feraille, 1984, Hijack Stories, Blood Money, the best in urban Bollywood …) might be organized as well.

This concatenation of events will be replaced, the following season, by another series of events and by another temporary structure, quite different thematically and formally: distinct, other, surprising. From one year to the next, visitors will never know what to expect. The complex, like its contents, will be ever-renewing. The structures themselves, however, will not die after they are struck. Part of the architect’s brief was to create something that can travel and, in another city, be put to a different use. Just as specific baseline strictures were given to her – relating to size, height, accessibility, climate, engineering, ecology, sensitivity to the historical, political and symbolic context of the complex – so too were broader, socially and politically grounded guidelines, to ensure that the structure created can have two, three or four lives: that it can continue growing. What she has proposed makes sense, practically and poetically: at mid-season, a call will go out to organisations across the continent (circuses, theatres, schools) that may have use for the temporary structure she has designed; applications will be sought – a text, photographs, a plan for further use of the structure – and, at season’s end, the structure will be crated and sent to one of the organisations, at whose hands it will live a new life.

Each new season will bring new artists and architects to work together in this place we are dreaming. They will be given free rein to devise and implement ideas. To coordinate their efforts, a point person will be on hand – a permanent staff member whose role will be to articulate the over-arching themes and ideas that give rise to the five interconnected shows, the interventions, formal performances and any other linked cultural events slated to take place each season. Ideally, this will be someone who straddles a number of fields, in terms of both interests and expertise – someone original, forward-thinking, open to dialogue and interested, above all, in pushing outward and far the bounds of the ordinary.

The foregoing is but one example of ways in which the goal might be actualised of creating a space such as we envision – a space wherein art is thought and experienced from the vantage point of a specific place and a specific time in Africa. The ideas explored here are not meant to be binding: they are a starting point. Any number of examples might have been introduced to start thinking about issues of definition, artistic freedom or audience engagement so central to this project. One could have looked to reception theory as explored and put into practice during Yoruba gelede festivals (one would be hard-put to find a better model for rethinking the relationship between audience and artist). One could have focused on the use of confusion and irony in fostering spectator engagement (a hallmark of Yinka Shonibare’s work). Consideration could have been given to the central role of improvisation – of the unexpected, from the standpoint of viewer/participant and artist alike – in adapting the work of art to the needs of the creator, his patron and the audiences each seeks to attract (tellings of the Epic of Sundjata Keita by Mali’s finest bards are exemplary in this respect). What is proposed here, then, is not a programme but an invitation: a door wide open onto possibility.

This piece features in the Chimurenga Magazine 15: The Curriculum is Everything (May 2010). To purchase as a PDF head to our online shop.