By Harry Garuba

The Palm-Wine Drunkard

Amos Tutuola

Faber and Faber (1952)

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

Amos Tutuola

Faber and Faber (1954)

If Amos Tutuola had not lived, and written stories in English, African literature would probably have had to invent him. So central has he been to the story of the making of modern African literature that it is difficult to imagine what or who else would have occupied the unique space he fills in the plot of this story. Without him, African imaginative writing in English would have been continually vexed by the melancholia of a “missing link”, because it would have had to account only speculatively and in abstract terms for the transition from the oral tale to the written text and from the indigenous languages of Africa to writing in the languages of European colonialism. Tutuola saves us all that ache and nostalgia, keeping at peaceful rest our conventional narratives of modern African and postcolonial literature and its transitions from one phase to the other.

The recent re-issue of Tutuola’s novels by Faber and Faber shows the continuing appeal of the works of this Nigerian novelist, whose first book, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, was published to international acclaim in 1952. That the 2014 edition carries an introduction by Wole Soyinka, the Nobel Prize-winning author, is significant because Tutuola’s countrymen scoffed at the accolades this novel received from reviewers in Europe and the USA when it was first published. By getting Soyinka to write this introduction, the publishers are, as it were, providing the final seal of authority that binds the initial international recognition to the belated embrace of the writer by his local constituency.

In a symbolic but very real sense, the Soyinka introduction signifies the coming together of local and global forms of cultural capital in a unified, consolidated endorsement of the Tutuola phenomenon. Just think T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, and then bring in Soyinka, and the picture is complete. I will risk the prediction that the Thomas extract, which has made it into every blurb of the many editions of the book since publication, will in later editions be supplemented with a Soyinka quotation. Shouldn’t we have one from Tutuola’s compatriot? Remember: we already have a Chinua Achebe quote on the blurb of this edition.

The Tutuola story is told again and again, yet it always bears further retelling. In a sense, it reads like an episode taken from one of his marvellous tales. A young man in one of the “bush” outposts of empire, with barely six years of formal schooling and a stuttering familiarity with English, decides to write a novel in the imperial language. He writes a tall, episodic tale, creaking at every joint, of an improbable protagonist journeying through worlds known and unknown, the world of the spirits, the gods, the dead and the unborn – all in a prose style that could only have come from the “African bush”. As the fates of Tutuola’s imaginative world would have had it, this handwritten manuscript lands on the desk of a certain T.S. Eliot, publisher at Faber and Faber, one of the high priests of literary modernism and, arguably, one of the most influential cultural arbiters of the 20th century.

Instead of thrashing this quaint object, Mr Eliot responds with curiosity – rather as Pablo Picasso was excited by those incomprehensible masks that had a career-changing effect on him. The question on Eliot’s mind must have been: how would a simple primitive, whose literary sensibility has been recently stirred by a smattering of English and a colonial, English education, write if he were so inclined? Is this the real thing – the first truly untainted “primitive” writing a novel in English? To answer the question, he sends the manuscript for review to none other than Dylan Thomas, the Welsh poet with a similar interest in primitivism. Thomas is equally fascinated and sends in a rave report. The book is published, complete with a facsimile of the author’s original handwritten manuscript, to authenticate his existence as a real person and not a figment of someone’s imagination. The rest, as they say, is history. Yes, perhaps this is a story that should begin with the classic folktale formula: Once upon a time… and end with: and the book lived happily ever after.

Certainly we will live happily ever after with the things that we love about Tutuola’s novels: the oral storytelling voice that suddenly announces its status as print, with the copious capitalisations and the many character names placed in inverted commas as in the graphological oddities in a Lagos signwriter’s workshop; the numerous titles that signal the entrance of a new unusual character or begin a new, bizarre episode; the references to monstrous creatures who trade in British pounds, shillings and pennies, with the little fractions of the currency noted in detail, and so on. Imagine this bit of reverse intertextuality: “Then I told my wife to jump on my back with our loads, at the same time, I commanded my juju which was given to me by ‘the Water Spirit Woman’ in the ‘Bush of Ghosts’ (the full story of the “Spirit Woman” appeared in the story book of the Wild Hunter in the Bush of Ghosts).”

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, Tutuola’s second novel, was published in 1952. But in this first novel, the narrator-protagonist is referring to it as an already “appeared” story book. In short, he is referencing a book yet to be published as if it were already in the public domain. Is this a form of oral intertextuality? Is there a realm in which all the stories of the world already exist, simply waiting for the artist to bring each to voice or into print? We are used to the notion of art imitating life; what are we to do with the proposition that art prefigures life? It is this sense of reversibility, this playfulness before postmodernism, this toying with our expectations, troubling our knowledge systems and classificatory grids and upsetting our categories (even our tenses) for grasping the world, which makes Tutuola’s world perennially fascinating. Though The Palm-Wine Drinkard remains his most engaging text, this quality is present in all his works.

As the Tutuola texts begin another phase of life with these 2014 editions, they once again stand at a crucial conjuncture in the institutional organisation of literature and literary studies. Within a decade of the publication of his first novel, African literature took its first tentative steps towards becoming a discipline of study in institutions of higher learning in Africa and elsewhere in the world. As we hurtle down the road towards what is increasingly being touted as World Literature, we need to take Tutuola’s texts with us, because they will help us reflect on and understand the implications of this new form of organisation of literary knowledge.

So much has been said about how Tutuola marks a crucial stage in the evolution of African writing, but one important part of his epochal significance remains unexplored. What the uneven reception history of The Palm-Wine Drinkard marks is that historical moment when a chasm arose between the local/national evaluation of a text and the international value attached to it. While the foreign reviewers thought highly of it, the local commentators were less impressed. In the usual course of literary evaluation, a text is first valued by the local audience in whose language it is written and this valuation usually passes on to the international audience. This often occurs through translations undertaken on the basis of the local construction of literary value, thus creating one extended circuit of value. But with Tutuola two circuits of value emerged and the divergence between the two could not have been wider. Happily, in the course of time, both circuits converged as the local commentators quickly conceded (implicitly) that they had been mistaken in their initial evaluation.

But were they really mistaken? Perhaps – but not entirely. In their assessments they were inserting the text into a local circuit of value, placing it beside works of a similar genre in the local tradition. In their estimation, read within this tradition, Tutuola’s novel falls short when placed beside the towering figure of D.O. Fagunwa, the pioneer of the Yoruba novel. Some went so far as to call Tutuola’s work a poor imitation. But Fagunwa’s works were not written in English, nor were they published in London; they were written in Yoruba, published in Lagos and sold through a local distribution infrastructure. Their publication was not mediated by an Eliot or Thomas or reviewers in The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker or The Observer, to name a few. In effect, they were largely limited to a local circuit of value. To use Soyinka’s apt phrase, they did not “suffer rediscovery by the external eye”.

What lesson can we take from this Tutuola story as we move into the future, as globalisation engulfs us and World Literature arrives at the doorsteps of academic institutions? The lesson is this: that while writers in local languages and writers of English texts published locally insert their texts into local/localised textual/social formations and these texts participate in local circuits of value, texts written in English and published in the metropolis are inserted into an international/global literary space and acquire value in relation to the value criteria and mechanisms operative within that space. While the former are often engaged in the project of national dialogue and partake in a local field of discourse, the latter enter into the international literary space, often on the basis of their distinct “civilisational” or geopolitical, cultural contribution. This is, of course, a different discursive field, usually with its own set of priorities and value criteria. Here is a Tutuola-esque image to describe this process: And a “MONSTER WITH ONE EYE FACING NORTH AND ONE EYE FACING SOUTH” entered the room.

What better image can there be to welcome the re-issue of Tutuola’s novels and to highlight the many lessons we can draw from them?

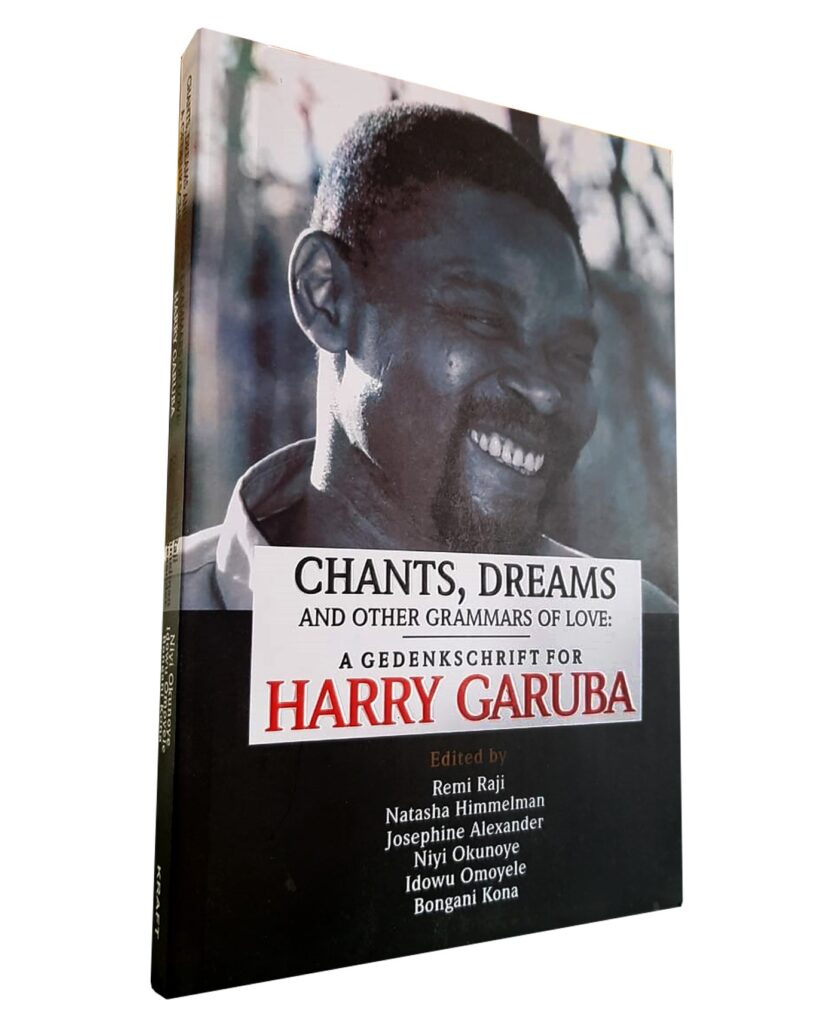

For a collection of reflections, reminiscences, critical reviews and poems, all dedicated to the memory of Harry Oludare Garuba, scholar-poet and professor in the Department of English and at the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town in South Africa visit Chants, Dreams and Other Grammars of Love: a gedenkschrift for Harry Garuba (Kraft Books Limited, 2022) at our online shop or visit Chimurenga Factory at 157 Victoria Road, Woodstock.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.