By Tolu Ogunlesi

On a per-person basis, South Africans drink four times more beer than Nigerians; as a country, South Africa enjoys ten times more electricity that thrice-as-populated Nigeria. So, before leaving the starting blocks, that’s already two goals to nil, against Nigeria.

South Africa’s universities are also better regarded, and are home to large numbers of young Nigerians on the quest for a decent education.

And then this: at any point in time there’s a horde of Nigerians trooping to South Africa to shoot music videos and commercials. Nigerian talk-show host Mo Abudu says most of Nigeria’s multi-million-dollar annual TV ad-spend ends up in South Africa.

On to sports, for the blow-of-all-blows: in 2010 South Africa became the first African country to host the World Cup. And they did a damn good job, better than Nigeria did when she hosted the 1999 Fifa World Youth Championship, and the Fifa Under-17 World Cup in 2009.

But Nigeria hasn’t always played second fiddle: In 1972, for example, Nigerian Akinola Aguda was appointed as Botswana’s first African Chief Justice; during the fight against apartheid Nigerian scholarships went to thousands of South Africans; the Nigerian government was a key supporter of the anti-apartheid movement in the 1970s and 1980s; and for a certain generation of Nigerian musicians, composing an anti-apartheid song was a rite of passage. No doubt Nigerians were very concerned about the predicament of their South African brothers and sisters. In the late 1980s former Nigerian President Obasanjo suggested employing voodoo in the battle for the liberation of South Africa.

But in 1994, the tables turned. South Africa began the transition to democracy, and cast off its decades-old pariah status, while Nigeria started a descent from darkness into deeper darkness, supervised by a dark-goggled dictator called Sani Abacha. Incensed by Nelson Mandela’s role in the international campaign to save the lives of Nigerian activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight others, Abacha ordered Nigeria’s boycott of the 1996 Nations Cup hosted by South Africa.

It wasn’t until Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 that tensions thawed, and Presidents Obasanjo and Thabo Mbeki (who both took office that year) forged a friendship that underpinned the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad).

In the thirteen years since, South African businesses have invaded Nigeria with the same aplomb with which we have invaded Ghana: MTN (which makes more money from Nigeria than anywhere else), Multichoice, Standard Bank and Shoprite have all made their marks, though Nandos and Nu-Metro didn’t survive their incursions and are no longer doing business in the country. Nigerians haven’t reciprocated on a similar scale, but worthy of mention is the historic 2005 listing of Nigerian oil company, Oando, on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

And of course the October 2003 launch of a South African edition of Nduka Obaigbena’s ThisDay newspaper, which, sadly, soon ran out of advertisers’ confidence, and money, and shut down in October 2004. According to Eno Bassey’s dissertation on the “rise and fall” of the newspaper: “ThisDay represented the first major financial investment from Nigeria to South Africa as opposed to the huge influx of South African investment into Nigeria.”

In May 2008, South African citizens turned against immigrants, including but not limited to Nigerians, in a series of violent xenophobic attacks. They complained that immigrants from other countries on the continent were stealing jobs, diminishing economic opportunity and, in the case of Nigerians, running criminal gangs of drug-dealers and fraudsters.

The following year, a feature film – District 9 – hit the screens, featuring as one of its main characters a paraplegic Nigerian weapons dealer and gang-leader named Obesandjo. (One is assuming it is only coincidental that a former Nigerian president is called Obasanjo.)

Nigerians protested. No less a person than the then Nigerian Minister for Information, Dora Akunyili, protested. The film, she insisted, was a gross misrepresentation of Nigeria and Nigerians. One of her complaints was that it portrayed Nigerians as people who “believe in the powers of ritual and voodoo”. It seemed that the Minister’s point was that only ‘Nollywood’ – currently busy on a continent-wide cultural colonisation project – is allowed to portray Nigerians in a dim light.

District 9 will always stand as incontrovertible evidence of the way Nigerians are generally perceived in South Africa. As South Africa’s High Commissioner to Nigeria, Kingsley Mamabola, told Nigerian paper, NEXT, “The perception South Africans have about Nigerians is not good at all. Those Nigerians of a very tiny percentage – I will say just about one percent – engage in crimes that are generally seen by all and which overshadow the good works of the majority of Nigerians.”

That perception might explain the treatment meted out to Nigerians at the dysfunctional South African embassy in Lagos, until recently, when the visa process was outsourced to the same firm that handles UK visa applications.

In March 2012, the South Africans almost succeeded in launching World War Three when 125 Nigerians – an entire plane-load – were refused entry at OR Tambo International airport in Johannesburg, allegedly for possessing fake Yellow Fever cards. An angry Nigerian government immediately triggered its emergency response system: within days Nigeria equalised, and then some. One hundred and thirty-six South Africans were sent packing, ostensibly to protect them from contracting the Yellow Fever that is responsible for Nigeria’s dysfunctional state. One of the most hilarious news reports from that time was the one that said 67 “South African prostitutes” were being deported from Nigeria. Until then few had any idea that South African business interests in Nigeria extended to the sex trade.

That contentious state of affairs ended as it should have, with a South African apology to Big Brother Nigeria: “We wish to humbly apologise to [Nigeria], and we have,” South African deputy foreign Minister Ibrahim Ibrahim was quoted as saying at a press conference called for that purpose.

Barely three months later, the two countries were back in the trenches, this time over the bid of South African Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma for the chair of the African Union Commission. Citing a previous gentlemanly agreement between the five leading countries in the AU, agreeing to not put forward their nationals for the position, Nigeria campaigned for the incumbent Jean Ping, from Gabon. This time, however, it was Nigeria’s turn to capitulate. Dlamini-Zuma emerged the winner of the election in October2012.

But no one should assume that the battle is over. As history has shown, there are no lasting peace accords, only shaky ceasefires between Africa’s two largest economies.

“Since the demise of apartheid, South Africans have not shown the kind of reciprocity one would expect of a brother,” Nigerian Wole Olaoye lamented in an editorial published in the Nigerian paper, Daily Trust, in August 2012.

Nigerians who share his view of South Africans as lacking brotherly goodwill will point mockingly at OR Tambo airport, the world-leader in luggage theft. My friend, A, survived a robbery attempt in Johannesburg last December – a gun to his head, and a casual quip reminding him that his Nigerian-ness was, at that moment, likely to count against his survival chances. I recently had a Nigerian tell me that the difference between Nigerian and South African robbers was this: Nigerians asked questions and weren’t likely to shoot; South Africans concerned themselves with shooting alone.

I’m sure South Africa has its own lines of defence. These might or might not include the suggestion that the OR Tambo luggage thieves are actually Nigerians, or that the robbers at Lagos’ Murtala Mohammed Airport actually wear government-approved uniforms.

The truth is that South Africa remains a safer (yes!) and saner place to do business, offering better infrastructure, less confusion and corruption, than Nigeria (Don’t rejoice yet; it’s not that hard to offer less corruption than the giant of Africa).

What Nigeria offers is freakish investment returns, which obey no known or unknown economic theories, and guaranteed only to a fortunate, super-risk-taking few.

It would definitely be hard to find any Nigerian who can argue that South Africa, even with its several challenges, isn’t miles ahead of us. If we had any doubts, the World Cup hosting feat silenced them all.

Where Nigerians will instead find solace is in the recent declarations of economic prophets, who say we will displace South Africa as Africa’s largest economy very soon. Standard Chartered says that magic year, when South Africa will begin to eat the dust thrown up by Nigeria’s speeding economy, is 2018. Morgan Stanley says 2025.

We will patiently wait for that moment when BRICS will fall into inevitable disuse, to be replaced by BRI-N-C. Headlines like “Africa on the BRINC of Global Domination” will remind the world that, were the continent to be re-imagined as a pistol, Nigeria, not South Africa, lies where the trigger would be.

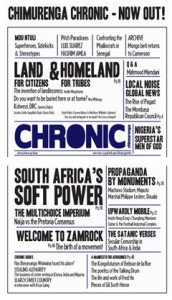

This story features in the Chronic (April 2013). Contributors to this edition of the newspaper include Jean-Pierre Bekolo, Binyanvanga Wainaina, Dominique Malaquais, Mahmood Mamdani, Niq Mhlongo, Paula Akugizibwe, Howard French, and Billy Kahora. Stories range from investigations into the business of moving corpses to the rhetoric of land theft and loss; from latent tensions between Africa’s most powerful nations to the soft power of the biggest satellite television provider; and from the unspoken history of Rushdie’s “word crimes” to the unwritten history of PAGAD.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurengashop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button]