By Dominique Malaquais

Photograph by Joel-Peter Witkin

Frantz is frowning. He is having trouble with his homework again. I would help, but I have nothing much to offer. With arithmetic or spelling, I could assist, but the matter is elsewhere. One word is bothering him. Violence. In fifteen years, it will become a cross for him; he will wrestle it, heavy, to hill tops. He doesn’t know this yet. And I know better than to tell him. I try to convince him that he is too young to consider such things. I fail.

We are sitting under a guava tree in the early evening. I read Flaubert. Later, he will disapprove. The first whiffs of dinner cooking reach us. The help is busy. Of this, I disapprove, but I am in no position to argue: I am being fed.

My name is Catla. I am Frantz’s latest project. My unkempt face – a beard, uneven curls, skin darker than his – drew his attention. That and my shoeless state. Decades later, I will read a short story about shoelessness in a magazine left lying on a café table, somewhere in Kenya. Frantz will come to mind, long dead but enjoying renewed interest – a mediocre biography, hip hoppers discovering and misappropriating his words. His mother was not amused, but Christian guilt got the better of her, and so I moved in. Frantz arranged a shed in the yard for me, near the tomato vines, provided books and clean sheets, which I hadn’t seen in some time.

Mostly, we talk about the world. The places I have been and those he plans to see. His biographers will insist that the desire to roam came to him late, after a disappointing sojourn in Paris. They are mistaken. At ten, already, he knew. Not that he would choose Algeria, or that it would choose him, however begrudging the choice. But that he would leave, yes.

We talk about my career, too. This we have kept from his mother. I am a thief, a robber of fine gems appropriated from pretty necks. In a bin near the town’s only viable theatre, I keep a change of clothes: a tuxedo and shoes, spit polished to a high gloss. A comb too, cologne and a pair of fancy boxers.

On nights the theatre receives visiting players, thrice monthly, I bathe in the sea and change into my fine threads. Dipping into the previous month’s haul, courtesy of a pawnbroker two towns away, I buy a balcony ticket and settle in to wait for the play. In my left hand, I hold a linen handkerchief, wet about the edges, and dab my eyes. Sooner or later, a young thing accompanying bespectacled parents brushes a hand against my forearm.

Why are you crying?

I tell a sad story of love lost. If time allows, I expand. She was white, like my new friend, or métisse if the tale fits better; I, though well-to-do, am black. Her family disapproved. She died at sea. Was called back to the metropolis. As the play progresses, inevitably, the young thing reaches for my hand. As she leaves, she slips me a note. An address. By dawn, I have done my business, decolonised her north and south. I only weep for girls with diamonds at the throat.

In his early twenties, Frantz reads Marx and writes me. In my shed days, in the shadow of his mother’s tomato vines, he thought my business amusing. Now he has doubts. Still, he would like to know, if I was as successful in the weep-and-swipe trade as it seems I was, why was I shoeless, homeless, bereft when he found me? I debate answering. In the end, I leave the question hanging. What explanation could I give? I was feeding a family? Seeing to a dying relative’s care? Getting my kicks? The truth would have confused him. And to what end?

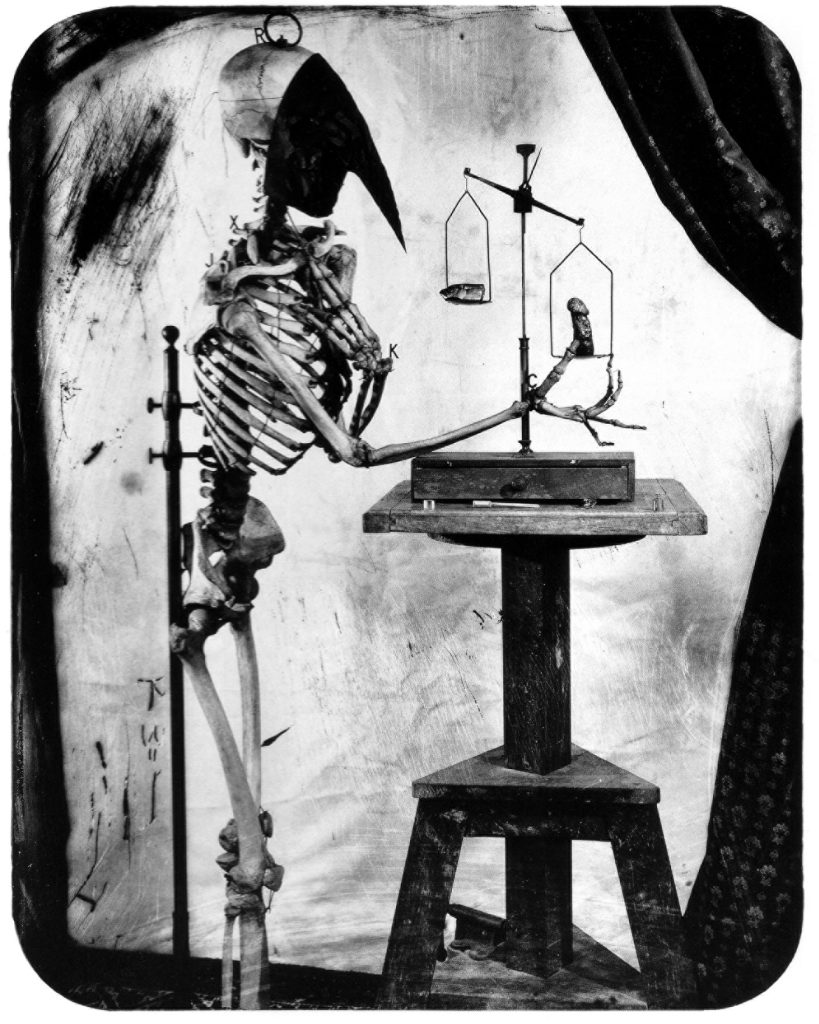

You’ve seen the relics of saints. Pathetic bone creatures encased in glass, encrusted with jewels, half forgotten in Bavarian churches the colour and texture of a cheap wedding cake. I was busy assembling a relic.

My plan had been to be an archaeologist. But I had not gone to school and had little money; travel to Paris or Berlin, to a university offering an archaeology degree, was out of the question. So I took to digging. Armed with a textbook published in 1903, Lexique illustré de l’ossature mammifère, I identified my finds: left femur, cat; metacarpal, colobus monkey; coccyx, rhesus monkey. Occasionally, I found a human part. Every bone, every shard was inventoried, wrapped in cloth and packed away in a trunk I had found on the shore. Three years into the process, I had enough to make a whole skeleton. An odd creature, of multiple, mismatched parts, but a complete creature all the same.

Attaching the various parts proved time consuming. In each, I bored multiple, tiny holes with the help of a shell, a method I had read about in a book on the Maori. Through each hole, I threaded fiber from a length of rope I had painstakingly unraveled. Each knot was a masterpiece, strong as steel, yet invisible to the naked eye. The exercise took a full year to complete. The biology textbooks that Frantz had lent me came in handy. I was able to make the most of bits and parts to create what was clearly a mosaic of unrelated bones, but a very convincing one, nonetheless.

The skeleton finished, I proceeded to sift through the gems I had stolen. The roundest, I reserved for the orbits. Both were flawless diamonds, a pair abducted from a smallish person with blue eyes and hair subjected too many years to the heat of irons. In each ear canal, I placed a diamond as well, of the variety used to make pinky rings – funnel-shaped at the base. On occasion, in my heists, with a diamond came another variety of stone. Lapis, for instance, an excellent choice, I found, to draw attention to the knuckles. A ruby or two, I positioned in strategic spots – at the base of the neck, where the spine meets the hips. Where the cartilage of a nose would have been, had I been dealing with a live or recently deceased being, I placed an emerald, the only one I ever landed. Each stone I attached with glue, a resist-any-cataclysm affair I had acquired from an Indian trader on Napoleon Road.

Coincidentally, I finished the relic on Frantz’s fifteenth birthday. I considered introducing him to my work on that day, but again relented. How could I present my creature to this young man convinced I had changed his life, set him on the course he had decided would be his? And convinced he was. The belief that I was his guide would never leave him, even in his moments of harshest doubt. Such was his conviction that, as the life was ebbing out of him in a hospital room outside Washington, DC, it was my name he called. Catla.

Predictably, his CIA minders misunderstood. Cala, they heard, which their feverish imaginations transformed into Kala and, naturally enough, into Kalashnikov. His final hours must have been dreadful, ‘specialists’ whispering questions into his cancer-eaten ears, demanding, then pleading, that, as St Peter’s gates loomed near, he give up the ghost of Kruschev’s tentacles, fast at work strangling the Kasbah’s last gasps of free enterprise.

Poor Frantz, who couldn’t tell an AK from a kickstand.

By Frantz’s sixteenth birthday, I had grown restless. I had been on the island for six years, longer than I had stayed anywhere. Even the shed by the tomato vines had me bored. I had read everything under the sun. And my relic needed seeing, by eyes other than my own.

I decided to travel the relic to Rome. In my readings, I had come across numerous texts on the island’s history. Few people could boast my knowledge of its past. In one book, I had discovered the existence, short and gone mostly unnoticed, of a nun, one Sr John of Patmos, to whom a variety of miracles were attributed. Further research turned up a diary by the sister, in which she had recorded her hatred of all things black and a commensurate dedication to washing all objects and people clean. Hence one of her ‘miracles’: the bleaching of a toddler’s skin in the early days of her stay on the island. I contacted the Vatican.

An archaeologist of some renown – I gave myself a name to match, Sir Richard Beaglehole-Bond – I wrote, on a windswept promontory I had come across a relic that could only be that of Sr John. I had approached the local historical society, I added, but had elicited little interest, not least, I suggested, because its caretakers were Protestants. I therefore found myself at a loss and held the relic at the Holy See’s disposal. A monk was dispatched. He arrived some months later, bearing a satchel-full of books on relics, saints and saints yet to be canonised. He had been entrusted with verifying the legitimacy of my claim.

It is the burden of such investigators to doubt: relics turn up with great regularity, all of which, statistically speaking, cannot be authentic. The monk sent by the See was doubt incarnate. But I was prepared. Clearly, he said, on first eyeing the relic, this could not be the skeleton of a human being. Clearly, I answered, whipping out Sr John’s diary. On page 87, the nun had written something odd: in the spirit of St Julian, she had discovered, late in life, that she had a fascination for animals; the smaller the creature, the greater her interest was in its wellbeing. Had she her way, she had written in the painstaking script of one educated just enough to cause harm, on her death she would be dismembered and reconstituted, lying in state, as a zoo – “a marvelous, Medici-like curio cabinet of small mammal parts.”

The woman was insane, of this I was fairly certain, but such things are par for the course where saints and seers are concerned, and so I didn’t bring it up. What I did note was that, self-evidently, her wishes had been fulfilled, likely by the person or persons who had seen to her transformation from corpse to relic.

The monk nodded. Such things, he informed me, though unusual, were not unheard of. This too I knew. Prepared for the possibility of just such an inquiry, I had compiled an inventory of similar cases, turning up one in Peru, a priest whose bones had been rearticulated with those of several rabbits, two in what was soon to become French Polynesia and a fourth in Rouen. All save one who, it appeared, had been the victim of an unpleasant post-mortem joke, had been adepts of St Julian. The monk was impressed with my knowledge.

The See’s investigation lasted some three months, prolonged, no doubt, by the monk’s discovery of papaya wine and mulatto breasts. In the end, I triumphed. My relic was pronounced res vera and I, of all things, sanus. Adsensio was granted. The relic was on its way to Rome.

I followed. A year later, Sr John was installed in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore. I had held out hope for St Peter’s, but clearly this was too much to ask. My nun, after all, had not yet been canonised. In any event, I was informed, this was a good choice, well adapted to the tropical exotica of the sister’s original resting place, Frantz’s island. She would lie in state near the bust of one Ne Vunda, the Kingdom of Kongo’s first ambassador to the Vatican (1604-1608).

As it turned out, the church stood in diametrical opposition to all things tropical. Legend has it that its plan was divinely inspired, its outline drawn on the ground by a miraculous snowfall said to have occurred in August of 358. In commemoration, every year, on August 5, white rose petals are dropped from the dome during the festal mass. My relic was in good company.

Frantz, later, would visit Santa Maria Maggiore – in the summer of 1958, to be exact. An explosive device had been attached to the underside of his car. When it went off, he was severely wounded. As he was convalescing in the Italian capital, the Red Hand had a go at him. I have often wondered if it was this second attempt that sent him – in desperation or sheer orneriness – to the church of Mary. I do not know if he witnessed the shower of roses, but like to imagine that he did. He would have known about Ne Vunda; a heathen rescued by the light of the papacy, smothered in white petals once yearly, would have been just the thing to lift his spirits.

I do know that he did not see the relic. By this time it had moved, off to an obscure Alsatian church, its exit hastened by the attentions of an American art historian who had found the one glitch in my story, which the Vatican, ever on the lookout for relics to add to its stash, had failed to notice: Sr John had died at sea. She had fallen victim to a vision of herself as a dolphin. Her body had never been recovered. Under the circumstances, a skeleton, even if partly of animal origin, was unlikely. The relic, a tribunal of hastily assembled monks had concluded, was not hers.

I had left Rome in a hurry. A few months ahead of Frantz’s visit, I boarded a ship for Senegal, where I did a brief stint in jail, organising, on the occasion, a strike among the Dakar penitentiary’s population of African inmates. On foot from there, I followed in Frantz’s steps, to Ghana, where his illness had first been diagnosed.

For a time, I hovered around the edges of Nkrumah’s fledgling government, serving in various peripheral capacities. I delivered food to his private quarters in the insomniac nights for which he was famous, wrote a speech or two, checked for bombs on the undercarriage of his car. Euphoria was in the air, but I had read Frantz’s words too closely to share in the mirth.

Behind bars in Dakar, I had written to Frantz. The letter took months to arrive, following him from city to city and country to country. It found him in Tunis. He responded almost immediately. The psychiatric hospitals of the USSR had broken his heart. He wrote of André Gide and his pathetic, misplaced hopes for Stalin’s gulag, of his dwindling hopes for change. This first letter was followed by a host of others, each containing passages of what would become The Wretched of the Earth. He had recovered enough to write, but his health was failing, and money was scarce. It was time to move the relic.

I left Accra for Paris, via London, and made my way to Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, the sleepy Alsatian town to which Sr John had been dispatched. Retrieving her from the Church of the Blessed Mary – on Chapel Street, of all places – was child’s play. I had kept one diamond, which I used to cut the glass in which she was encased, folded her at the hips and hoisted her into a large army bag.

By 8am, I was on the train to Germany. East Berlin was my destination. For passage through Checkpoint Charlie, I donned a US army surplus jacket, GI Joe’s stolid grin and a medic’s ID, stolen the previous evening in a bar at the edge of the city. Sr John reached Communist Europe slung across my left shoulder.

For all the KGB’s efforts, the USSR remained a fervently religious state. Relegated to the outer margins of official society, its churches were starved for miracles. Sr John would find a happy home there. Within days, I had three takers: parishes eager to welcome into their fold a relic that had once lain mere feet from the tomb of Pope Nicolas IV.

As I intended to net quite a bit for her remains, I decided to sweeten the deal. To the skeleton and its gems, I added a letter authenticating the relic, signed by a descendent of the Medici family, whom I christened Lorenzino, in honour of the famous skirt-chaser, occasional rapist and all-around lout. Lorenzino, I informed the potential buyers, had acquired the relic on Frantz’s island and placed it, on loan, with the overseers of Santa Maria Maggiore. Failure to pay his accounts, the result of an unhappy foray into arms dealing in the vicinity of what would one day become Mozambique, had brought him to retrieve the relic. He now wished to sell it in order to recoup his losses and had put me in charge of finding a suitable buyer.

A Siberian church acquired Sr John. I pocketed the tidy sum of $10,000, which I promptly wired to Frantz. Why he chose to take the money to the United States, to Bethesda Naval Hospital of all places, escapes me. Certainly, the care was good. But to die there? Him?

By post, I had sent him a tibia, one of the few parts of Sr John’s ‘body’ that had come from a human skeleton. He never received it: it arrived after his departure for America. Why, precisely, I sent it, I still do not know. No explanations accompanied the bone – again, what could I have I said? Still, I like to think that, had it reached him in time, he would have perceived the insanity of death in a land born of hatred for everything he had come to represent. Then again, what difference would it have made?

Frantz died on December 6, 1961. He was 36 years old.

The years following his death were aimless ones for me. Angola, Sweden, Chile. Even Irian Jaya, briefly. On his deathbed, Frantz had requested to be buried on Algerian soil; he was – a stone’s throw from the Tunisian border. Much was made of his dying wish among the upper echelons of the FLN. By the late 60s, he had become a full-fledged national hero. Had he been in a position to witness goings on in the country he had fought so hard to liberate, had he seen how fast the FLN government was morphing into a shadow, nay a carbon copy, of the French overlord, Frantz would have blown up his own grave in disgust.

In 1999, I decided that something needed to be done. The gesture was futile: I knew it even as I began digging. But it was the only solution I could muster. I disinterred Frantz.

Months and months of walking, his bones slung across my back, brought me to the outskirts of Paris. I had a plan.

The French capital was abuzz with talk of a new law: Muslim girls would be forbidden to wear the veil in school. Organised religion raises my every hackle: no fan of the veil, cross or yarmulke I. But I had read Frantz on the women of Algeria, and I had perused – with glee – the columns of the Figaro as the Evian agreements loomed, relished the purple phrases of its reporters warning of bombs hidden under the long black wraps of Algiers’ militantes. Some manner or retort was in order.

On the Champs Elysées stands the Arc de Triomphe, one of the ugliest clusters of neo-classical marble ever erected. At its foot lies the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. A flame is kept alight there, day in and day out, 365 days a year. When politricks require, the president drops by, surrounded by ministers of state, clergy and baby-faced soldiers, their skin chafing under the weight of uniforms and guns. The Tomb celebrates those who died fighting the Germans in the two world wars. The bones are those of a white man, un français de souche: no reference here to the tirailleurs sénégalais and other hapless colonised souls who fought for the mother metropolis.

Getting to the tomb was no small feat. It required a tunnel, the digging of which took me four years. In July 2004, mere days ahead of the country-wide celebrations held to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Paris, I dragged Frantz through the bowels of the city. Pick and chisel in hand, I bored into the tomb.

Two days later, President Jacques Chirac knelt before the Unknown Soldier. As he rose, he placed a spray of orchids at Frantz’s feet, honouring Sr John’s tibia in the bargain.

On Independence Day, in Algeria, a wreath of flowers is deposited on Frantz’s tomb. Cool in the earth below, I breathe their desert breath.

This piece features in the Chimurenga Magazine 10: Footbal, Politricks & Ostentatious Cripples (December 2006). To purchase in print, or as a PDF, head to our online shop.