by Keorapetse Kgositsile

Returning home, even though just for a short visit, for the first time in twenty-nine years, as John Oliver Killens might have put it, is a humdinger. Jan Smuts Airport is a seemingly huge, clean, efficient monstrosity. Its size is more shadow than substance, though. No huge nothing about it. Monstrosity, yes. Dimly lit inside; eerie like a veritable cave of horrors. After we have been vomited at the ‘arrivals’ entrance by the bus from the plane, we walk in: Patricia, her two daughters Thandi and Lebo; and I, and many other passengers. And now the shit begins to hit the fan. South Africa does not celebrate the return of one of her many, many children from exile.

We queue up with those with ‘non-South African passports’. In your own country! Deal with that! After a few minutes an immigration officer comes and takes our passports, Patricia’s and mine and, after telling us to go and sit down ‘over there’ where our eyes follow his official finger, he disappears with our passports. I’ve just overheard him telling Zanele that she did not have a return visa. ‘But,’ she says to him: ‘in the past few months I’ve been in and out of the country several times.’ After a while Zanele is cleared. She can go into her country and, we learn from Bunny who has a multiple entry visa, ‘valid for the next three months’ into his own country, that Thabo has just arrived from abroad and is waiting for her ‘upstairs’. I wait. I begin getting anxious. I say to myself, ‘I hope diefokken boere are not going to put me on the next flight back to Lusaka.’ Ages pass. A burden of agitated rocks is threatening to do battle in my stomach. I decide to go to the bar upstairs to cool their temper or distract them with a beer. After gulping one down quickly I go down again to wait ‘over there’. After more ages comes Mr Immigration. He gives my Ghana passport to a beach-looking, pink-cheeked, young woman who gives me back my passport and says, ‘You can go that way’. And she walks away fast. I walk to the counter and ask one of her colleagues what she meant.

‘Go out here and collect your luggage.’

‘You mean I’ve been allowed in?’

‘Yes.’

Quicker than soon I collect it. Junaid is there. So are Thabo and Zanele and Patricia’s parents. I tell Patricia’s parents she should be out soon and Junaid and I take the drive into Johannesburg.

On our way, Daphne with us, I do not recognize anything I could relate to. How is your Setswana, she asks. Dangerously good, I tell her; Setswana A, sa ga Monyaise. You know, in my opinion, old man Monyaise is one of our best living novelists. But because he writes in Setswana he is not known outside of a bit of South Africa and Botswana. Soon I will translate his work. I owe it to him. He taught me Setswana and Afrikaans literature and language in Form IV and Form V at Madibane High School, Western Native Township, Johannesburg.

COSAW Office. Heita Majita, Die Ouens, Boys, Gents! Here are my colleagues and hosts. Can you deal with that? Hosts! In my own country. Junaid disappears. After a while he comes to call me to another office, to a phone. On the way: ‘Hey broer, we are under fire from Baleka.’ Baleka, Baleka uncompromising fighter through and through. One of these days she’ll be the death of me, in loving care and concern, I hope. ‘How can I learn only from the papers today about your being here?’ she wants to know. ‘You know, even I didn’t know I was coming here until yesterday. Like Junaid says, COSAW sent you afax. But evidently you didn’t get it.’ ‘Well, I don’t even have a place to stay,’ she says, ‘so where are we going to stay?’ ‘I’ll sort it out with COSAW,’ I try to allay her fears. And it is quickly sorted out. Protea Gardens Hotel, Berea.

But first to ANC Headquarters at 54 Sauer Street. There’s Baleka there, pretending, unsuccessfully, not to be particularly impressed to see me at home. There’s Barbara, ‘Thembi’ and Zanele, loving sisters and comrades from way, way back. Hugs, embraces, kisses, gleeful smiles. My sisters. Home at last, home at last. But wait boet, wait. I can almost here ou ‘Mabuafela’ Jimmy Jackson say, these young fools are in a moer se hurry ek sejou. Bas’pidile. But Congress is an old, old man, boet, with a long, long beard. But wait a minute. Ya. Johannesburg. Home, Ya? But I do not know this place. I know some people who have remained alive, perhaps miraculously, from the old days. I avoid to meet too many people at ANC Headquarters. Selfish, perhaps even cowardly selfish, yes. Afraid to confront a past that has been immobilised or obliterated by apartheid and supposedly progress—whatever that might be supposed to mean in the context of latter-part twentieth-century South Africa.

Baleka has warned me against my expectations. And, you know, I suspect the most treacherous thing about expectation, at whatever level, in the same way that frustrated want tends to turn into pressing need, is that it so quickly turns into DEMAND. Ask anyone with memory which, as Zinga correctly says, is the weapon. But there are no memories here. The streets of Johannesburg cannot claim me. I cannot claim them either. Their names, like Market or Commissioner, Bree or Diagonal, remain, but it seems there is not much more than that for the returning one after ages and ages. And, delinquent brother and kind sister, if here and there I could be accused of having some sense, I would like to state something simple and seemingly obvious. Even at a very physical level, you cannot — or should I say — you should not destroy everything which connects people to history, to certain memories, to certain places, to memorial reference points. If you destroy even those points of reference, you are not just destroying the memory; you are destroying even the notion of historicity: you are destroying the link with any past and present, which should inform the future. Even at a very physical level, you destroy those physical points of reference, you destroy the individual, the compatriot, the son or daughter returning ‘home’.

Day after my arrival. Market Theatre. Other chapters of history unfold. Over the past number of years we in exile have known of the Market Theatre. But I,personally, did not have the vaguest idea about even where it was located in Johannesburg. The old fruit and vegetable market. ‘Wake up early in the morning go to the market go buy orange nabble orange avocado coconut come kappirboy steal my nabble orange. Hit kappirboy. Mr Magistrate want to sentence me then Mr Magistrate head full of water same like coconut also.’ And guess, walking around, whom I run into, right here; Charlie Cobb and his wife Anne. Brother and comrade from across the big waters, doing a piece on South Africa for a special issue of National Geographic. It goes back and back — Washington, D.C.; New York, Africa — so many years I’d feel guilty if I said any more than that I was so excited that, like James Brown, I could have jumped back and kissed myself.

‘Hey, I was looking at the paper yesterday and saw your book was being launched here today. Did you get my message?’

‘Yea, I did. But the comrade didn’t recall the name too clearly. And when he heard you were AMERICAN, he was not exceptionally impressed. But I told him it might be you. So here ’tis. Whatshappening?’

Charlie, you remember your old piece, way way back during the old SNCC days, when you tried to grab us by the elbow to remind us of collected and collective memory and wisdom:

It’s not the size of the ship

It’s the motion of the ocean

Junaid has warned me, soon after my arrival, Broer there will be no rest for you. Of course initially I don’t take that too seriously; I guess only because here and there I am capable of being an embarrassing fool, consciously or unwittingly.

Mxo has asked me, the second day after my return, no, not return, arrival in this strange place, how was Soweto after all this time? No, man, I was booked at Protea Gardens. What? I don’ t think that was quite correct, he says. Well, later my younger cousin, France, phones. He read about my arrival in the newspaper. They are all excited ‘here at home’ — which means practically every part of Soweto—and they are waiting for me. Boet, I’m in Berea, ek se, and I have a very tight programme.

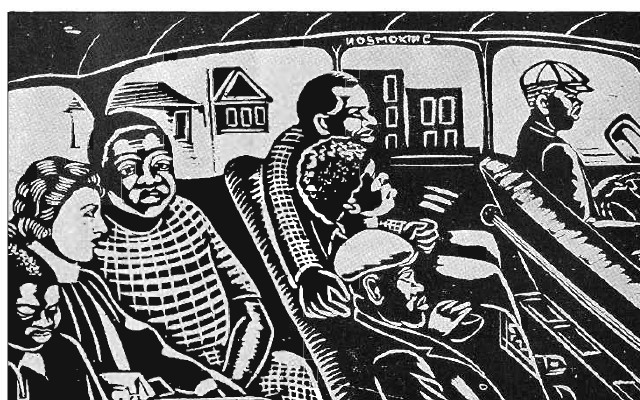

Things happen very fast here. After the book launch at the Market Theatre, a day to retrace some footsteps. I would prefer to walk from Berea, through Hillbrow, down Twist, past Union Grounds and the Alex Bus Rank, to Park Station, then down Jeppe or Bree to Diagonal and the old Sophiatown and Western Native Township Bus Ranks. But Baleka has not brought a pair of walking shoes from her ‘underground’ flat in Yeoville, for the long walk. So we settle for a bus. On the bus, ‘Eh, bra Willie you are here?’ An old young friend from the Jazz Pioneers. Baby We, I say to Baleka, check. They have performed together, the two of them, in Botswana and Holland, with the Jazz Pioneers. Maybe I am getting closer to home. At Park Station we part. Raks, Doreen, Baleka and I walk down to Diagonal.

Down the streets. No memorial points of reference. Therefore, return? Return to what? This place is foreign. I might as well have been wandering and wondering through any other part of this planet that I am not native to. Neruda says:

I know only the skin of the earth

And I know it has no name

A few years ago an old woman in Botswana, one of Jehovah’s most militantly devout children — I guess there must be some deal between him and them that they will never grow to be men and women, even if they lived to be older than old age itself— who had seen the remains of Tiro after the enemy explosives had reduced him to tiny strips of flesh, scorched dry and clinging to the ceiling — was very impatient with the likes of me for concerns about the liberation of my country. ‘Your country?’ she explodes. ‘Did you ever build a portion of this Earth, which you can claim as yours? I thought you were supposed to be educated! Don’t you know this whole Earth belongs to God?’

As I walk down this impersonal, concrete, marble, glass and synthetic nonsense, I want to scream COME THUNDER! CONFLAGRATION! Where are you! The Bigger Thomas in me wants to blot all this perverse shit out of existence. And let no limp-minded charlatan try to tell me my responses are unscientific. Because I will tell you right here and now that, like Castro, no force on this planet can move me from conviction about the principles of socialism. To the bitter end. Socialism or Death. Daarskak in die land. If you don’t believe it, ask Sandile Dikeni.

There are many changes here. But no change, no progress. I am referring to the spiritual and material quality of human life and living. There is a level of decay in the moral fibre of our society which, until now, could not have vaguely formed part of even my most bizarre nightmares. Incest, the rape of even infants, prostitution, barbaric violence and bloodshed, frightening levels of illiteracy, homelessness, large derelict areas of towns where men, women and children seem more irrevocably derelict than their physical surroundings, and many, many more perversions. Perhaps there is only one modern monster which readily comes to mind by way of comparison — the Unites States of America.

Let me give you a little taste of what I’m trying to say. During the reception after the book launch at the Market Theatre, this young fellow — certainly born about a decade after I had left home — comes and joins us at our table. He is an aspiring writer, he says; and he really likes my work. He frequents the Transvaal regional office of COSAW to type his work and to use the Can Themba Reading Room. After a while he tells us about how one day he and a few other ‘comrades’ had decided they had had enough of Inkatha raids and massacres and they were going to ‘show them’. So they managed to get hold of one Inkatha fellow. They doused him ‘good with plenty of petrol’ and forced him to drink some. When the fellow started to holler they sprang back and set him ablaze. There was an explosion, and that was the end of the fellow, ash to ash — and not figuratively, mind you. What they did was not as horrifying and chillingly mesmerizing as the relish with which he told his story.

When he saw the intensity of the surprise and the shock going amok through Baleka’s eyes, in a voice as serious as any heart-attack he continued, ‘Yes, Sisi, if we found out that you had anything to do with Inkatha, we would deal with you like that with pleasure.’

Curious as I am about what he writes, I am certainly more than a little bit frightened that one of these days, right there in the Can Themba Reading Room, he might ask me to read a piece of his and give him a comment. Wouldn’t you?

Delinquent brother, kind loving sister, comrade, I will not claim to know much about how some things in the everyday ordering of our lives could be explained. You see, at one level, my being here is a homecoming, in terms of the one who has been away. But at another level, the returning one has never left. An uncle of mine was very proud, for instance, that in spite of how long I’ve been gone and been all over the world, I have not forgotten my language. But finally, what could that possibly mean, really? Was I expected or suspected to ‘return’ a foreigner, mumbling some unintelligible gibberish, or what? My people, I went away yes. I crossed borders and borders, many of them illegally yes. But I never left. Even if I had wanted to ‘leave’ my language would not have allowed it; my memories and our collective memory would not have allowed it; my concerns, my daily preoccupations, would not have allowed it. Wally and Bra Zeke, remember one day in Philadelphia, years and years ago, I told you some day I would make this English speak my language!

Okay. For a while let’ s move away from Johannesburg; I’m sure by now you have realised that for me it leaves a bit of a bad taste in the mouth, or whatever crevice of the sensibility it lingers around. Junaid, as I said earlier, has already warned me: Broer, you better take advantage of your first two days here. After that, NO REST. But, like the fool I am, I do not take his advice seriously. After a few days in the country, my programme seriously begins. Eastern Cape, Western Cape, back to Johannesburg — but maybe I should say Jan Smuts, because on my arrival at Jan Smuts from Cape Town I’m whisked from the airport straight to Northern Transvaal. However, at the end of Lesego’s reading of a few of his poems, our eyes almost jump out of their sockets in surprise and to Lesego’s considerable chagrin and frustration when we hear this young Mzwakhe fanatic, applauding Lesego with ‘VIVA MZWAKHE! VIVA!’. The welcome was very moving. As we were about to drive back to Johannesburg, though, there was this comment from that rural corner of our country: ‘Comrade, for months now we have been hearing that a number of our people and our leaders from outside are back. But you are the first one to visit us. Why are we being neglected?’ Well, Leadership, it seems like a valid and a burning question to me. Please account to the people, honestly.

We arrive back in Johannesburg at night, exhausted. The following day, Durban for a few hours. Late at night off to Umtata. Junaid and Mi stay in Umtata just long enough to freshen up and have a meal; they are rushing back for a meeting in Durban. I spend the night. Early the following morning back to Durban. My children are not happy about this but they understand, whatever that means to a child who rarely spends time with his or her parents. My Durban-Johannesburg flight delayed. Finally on arrival at Jan Smuts, straight to the Free State — Welkom. Because of this lateness we cannot stop at Kroonstad where Antjie Krog has prepared all kinds of edibles for us.

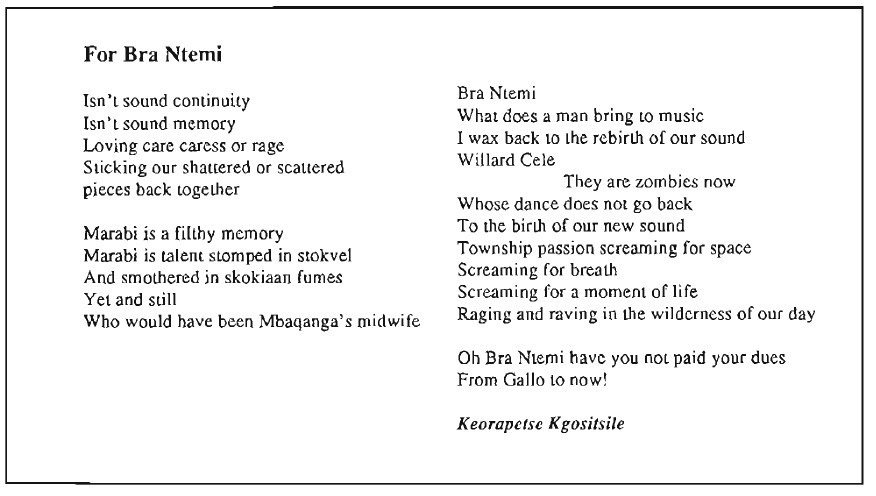

I’ve been desperately trying to get hold of Bra Ntemi — Ntemi Piliso of the legendary African Jazz Pioneers. Finally, one afternoon, Menzi, Lesego (Less Ego to some people), and I drive to Alexandra, to the Alex Arts Centre where Bra Ntemi is reproducing himself, teaching younger musicians music theory and equipping them with skills to play.

The Alex Arts Centre is up on that little hill at the northern end of a number of streets, among them Five. When our car pulls up and stops in the yard Bra Ntemi is standing at the corner of the wire fence overlooking Five. We quickly pile out of the car. Bra Ntemi takes a quick look at us and just as quickly turns his head again to resume his vigil on Five. We join him at the corner of the fence. No word from him. We join the vigil. We have walked smack-bang into the terror and barbaric violence called Operation Iron Fist.

The Law’, armed with brutality, hatred, rifles and other weapons, is harassing and terrorising the unarmed people of Alex. As these brutes move up the street— and there are many of them, I tell you — some of them, weapons menacingly at the ready, take positions on both sides of the street as their colleagues raid residents’ yards, houses, shacks and persons.

After a few minutes — but really, how do you measure time in a situation like this? — Bra Ntemi turns around, hugs and embraces me. Then, with a mischievous grin, he points at the violated street and says: Welcome Home!

There’s a young trumpeter at the far end of the yard doing his practicals. They teach theory and practice here. Bra Ntemi goes over to him, gives him some tips on how to handle certain licks several different ways and comes back to where Menzi, Lesego and I are waiting for him Then Bra Ntemi and I go to his office. Mandla joins us later. Menzi and Lesego leave to attend to some other duties.

The last time we were together was at CASA (Culture in Another South Africa) in Amsterdam, December 1987. For a while the whole world rotates through our tongues. CASA, AABN, Mbaqanga, Kingforce, Marabi, Swing, Jazz, Freedom Melody where Bra Klein tjie played his old trumpet which is probably my age, about which he told my enthralled daughter Ipe, ‘My baby, I grew up your father on this very horn’, the one and only Katse about whom legends are legion, Exile, AMANDLA!, Abdulla Ibrahim and Satimar Gwangwa, Dorothy Masuku, Hugh aka Huge Makasela in certain parts of our continent, Letta and Caiphus, Dorkay House, Gallo, SADF Raids, Inkatha, Sanctions, the Cultural Boycott, Kippie and many other late jazz giants at home and abroad, ANC and MK, Wally, Thami Mnyele, Baleka, Barbara, ou Tom (Nkobi) en ou Alf (Nzo) hulle—as Bra Ntemi says — the return of exiles, Mandela, De Klerk, the Alex Arts Centre, Funding, Kagiso Trust, SAMA, COS AW, and on and on. You’d be surprised at how much your tongue can cover in a few minutes. But then again, haven’t music and poetry striven to do just that since time immemorial.

The last time we were together was at CASA (Culture in Another South Africa) in Amsterdam, December 1987. For a while the whole world rotates through our tongues. CASA, AABN, Mbaqanga, Kingforce, Marabi, Swing, Jazz, Freedom Melody where Bra Klein tjie played his old trumpet which is probably my age, about which he told my enthralled daughter Ipe, ‘My baby, I grew up your father on this very horn’, the one and only Katse about whom legends are legion, Exile, AMANDLA!, Abdulla Ibrahim and Satimar Gwangwa, Dorothy Masuku, Hugh aka Huge Makasela in certain parts of our continent, Letta and Caiphus, Dorkay House, Gallo, SADF Raids, Inkatha, Sanctions, the Cultural Boycott, Kippie and many other late jazz giants at home and abroad, ANC and MK, Wally, Thami Mnyele, Baleka, Barbara, ou Tom (Nkobi) en ou Alf (Nzo) hulle—as Bra Ntemi says — the return of exiles, Mandela, De Klerk, the Alex Arts Centre, Funding, Kagiso Trust, SAMA, COS AW, and on and on. You’d be surprised at how much your tongue can cover in a few minutes. But then again, haven’t music and poetry striven to do just that since time immemorial.

Now we go and have a look at some of the other work being done at the centre. In one part of the building potters, sculptors and graphic artists share the space in which they work, rub shoulders, share jokes, stories, imaginative ideas and other juicy slices of life. Upstairs is where music happens. On the walls as you go into what seems like a lobby as you approach the rooms from which music bids you welcome, is a hypnotic festival. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Count Basie, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Ben Webster, Monk, Mingus, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Jackie Maclean, Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, and many, many more jazz greats with their condensed biographies next to or below them, their axes held in combat readiness. Your whole being glows and your soul melts. In two adjoining rehearsal rooms younger musicians are working out their history, defining their space and picking up their generation’s mission, with their instruments.

Rending, yes. Like the end of peace Gwen Brooks and I fear so much. That’s what leaving the Alex Arts Centre feels like to me. But we have to go. Practically everywhere I have been since I have been here, in addition to many other people I knew from the old days or from here and there in many different parts of the world in the past three decades, I met many younger writers, other cultural workers and activists, a lot of whom had not existed even as possible ideas in their parents’ imagination when I left home. Usually, when we met, there would be a little amused giggle or mischievous grin from them as we shook hands and hugged or kissed, depending on the gender. When I would want to find out what the joke was so that we could share it if I also found it funny, one or several of them would recite some of my work, complete with the sound of my voice to the degree that had I heard the recitation without seeing who was reciting, I would probably have said, ‘Wonder when I recorded that.’ Perhaps that was my Homecoming!

First published in Staffrider, Volume 9 Number 4 1991.