Panashe Chigumadzi travels to the rural Zimbabwe of her ancestors, onto land stolen and cash-cropped by a privileged minority under racist white rule. Now, almost 40 years since independence, millions of hectares have been returned to those whose birthright the soil is. Chigumadzi discovers that the land reform programme that drives agricultural transformation and justice for dispossessed Africans carries with it the promise of a future, and the pain and patriarchy of the past.

[Image: The author’s grandparents, Mbuya Beneta Chiganze and Sekuru Dickson Chiganze , in front of their farm at Gandiya Village, Makoni District, Manicaland Province.]

OLIVER MTUKUDZI’S “MURIMI MUNHU” (A farmer is a person), is playing for the second time in 12 hours on a local radio station. We are returning to Harare after spending Christmas with family in the ruzevha, what the Rhodesian colonial administration called “native reserves”. This second time I hear it, we are passing a billboard in the agricultural town of Marondera. To motorists and pedestrians, a seed or fertiliser company declares “Kohwa pakuru!” (Reap a big harvest!). After years of difficulty, agricultural productivity levels are rising, in many cases approaching pre-land-reform levels, as small farmers, like the one on the billboard and the family members we have visited this Christmas are gaining in expertise and experience. The song feels fitting for this time.

At the time of the song’s release back in 2001, the Fast Track Land Redistribution Program (FTLRP) was taking place. Understandably, there were many questions around Tuku’s message. Who was, or is, the murimi Tuku was referring to? It was possible to interpret the song in light of the stories of violence, thuggery, lawlessness, cronyism, destitution, incompetence and agricultural sector collapse that dominated press reports and, indeed, much academic analysis of the radical program.

To really understand the complexity behind Tuku’s assertion that a farmer is a person, you would need to know what is meant when a person of Bantu origin asks the question: “Mhunhu here?” (Is this a person?) It is a question you can only engage through an understanding of how southern Africa’s Bantu-language speakers conceptualise personhood and humanity. It’s not according to Enlightenment philosophy contained in Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think therefore I am”, but rather through the aphorism, “a person is a person through others.” This is central to the philosophy of ethical personhood known as Hunhu in Shona, and more popularly known by its Zulu equivalent, ubuntu. To paraphrase philosopher Ndumiso Dladla, to ask if someone is a person is a question of ethical character, having nothing to do with their biology or race, but with the history of their interactions with other people, and whether it can be said that they have conducted themselves humanely, that is, with Hunhu. The judgement of character can be also extended to a group of people with a history of interactions with a given Bantu-speaking community. The history of white settlers’ unjust conquest of Zimbabwe’s land and indigenous people, has seen it that when wanting to know the race of a person it is possible to ask, “Mhunhu here?” and, should the person be white, it’s appropriate to answer, “Aiwa, murungu.” (No, they are a white person.) In other words, varungu (white settlers) haven’t historically been considered vanhu (human), because they failed to treat the indigenous people with Hunhu.

Understanding this, you would have to ask, whose humanity was Tuku affirming? The white farmers who dehumanised Africans as they dispossessed them of their land? The new black farmers whose ancestral land was returned to them?

In the months that follow I think about this audio-visual moment. A song that subtly explores the historical questions of humanity and dignity implied by the land question; an image that depicts a triumphant smallholding farmer reaping his large harvest. Together, they bring to mind the “bread and, above all, dignity” Fanon spoke of as the concrete value of the return of the colonised’s land.

In the time since Tuku’s song was released, the picture of what land reform means for the majority of its beneficiaries, the small farmers, is not entirely coherent. There are many lenses through which to view the picture – the history of African land dispossession, post-land reform livelihoods, the cost to the economy – but what is clear is that it is not a picture of unmitigated disaster, nor of unblemished success. To understand the bigger picture, you need many smaller, variegated pictures of the successes and failures in agricultural production. You need to desegregate the results according to crop, livestock, institutions, climatic conditions, inherited infrastructure and access to farming resources, to gain a nuanced perspective.

“ALL OF THIS USED TO BE BOB’S LAND,” my father points to vast tracts of land to our left and right. It is “Bob’s land” for a good number of kilometres. It is mid-morning on 24 December. We are passing through “Bob’s land” en route to my mother’s rural home in Makoni district in eastern Zimbabwe.

Along the 80 km drive north-east of Harare to Murehwa in Mashonaland East Province, the landscape varies – some fields are growing weeds, some fields are being cultivated, some are doing both. Take a left at the Murehwa Centre turn-off and you will find grain silos, which until last year were disused but came back into commission as part of government’s Command Agriculture program, towering in the boulder-strewn landscape. Nearby, there is a landing strip, which used to serve the the Rhodesian army and white commercial farmers in the area. Take a right, and you are on your way to our family home kumaruzheva, or part of the communal lands that used to be Murehwa’s “Tribal Trust Lands” (TTLs), created to clear Africans off the best soils reserved for large commercial farms like the one belonging to Bob.

Under the 1930 Land Apportionment Act, 51 per cent of the best land in Zimbabwe was reserved for about 50,000 white settlers, while 30 per cent of land, with poorer soils, was reserved for one million Africans. This dual agricultural regime created a highly developed agricultural sector in which white farmers enjoyed private titles and massive state intervention, and an underdeveloped black agricultural sector where blacks continued to be governed by customary law, lack of land and substandard support services. At independence, the new government inherited an economy firmly anchored on a domestic white landowning class, allied with international capital, and domestically controlling (directly and indirectly) Zimbabwe’s financial, agro-input, processing and marketing subsectors.

Bob, unlike many other farmers, did not have a distinctive nickname like Manyepo, so named for his paranoia about the supposed lies told to him by the long-suffering workers of Chenjerai Hove’s 1989 novel, Bones. At least not one known to my father. My father doesn’t remember his surname. He was simply known to him as Bob. Bob, who owned the big farm bordering their ruzevha. Bob, who drove a Benz, which you would hear from afar, zipping up and down the graded dust road. Bob, whom he, as a school child in the early war years, had seen marching up and down in patrol with the Rhodesian soldiers. Bob, whose wife was a nurse, administering medical care to the natives in the surrounding reserves. Bob, who it was said eventually relocated to town because his wife wanted to practice medicine.

Bob’s land has many new owners now. Farm life is no longer divided between makomboni (workers’ compounds) and the well-appointed farm house. Dotted across the landscape are the neo- traditional homestead set ups, typically with a grass-thatched hut kitchen and one or more dhanduru, the brick four corner dining room where the families can either sit and listen to the radio, or sleep. The more successful have asbestos or corrugated zinc roofing, but for the poorest of farmers, these structures may all be mud, pole and grass. Moving in the distance you might see some of the new owners struggling behind ox-drawn ploughs or moving across their fields with hoes slung over their shoulders. Sometimes, a tractor might be seen taking its owner to the local growth point to get supplies. Globally and locally, the back-breaking efforts of these small farmers are often contrasted against mechanised efforts of the likes of Bob, who earned Zimbabwe that overused cliché as the “breadbasket of the continent”.

The landscape that used to be dominated by 4,500 mostly white, large-scale commercial farmers has been broken up by the FTLRP’s two-tier program: the A1 small farms with six hectares or less, which are geared towards poverty alleviation and are allocated at the local level, and the A2 large commercial farms, which aim to “indigenise wealth” and are allocated at the national level. The landscape is now populated by around 145,000 smallholders occupying 4.1 million hectares, and around 23,000 medium-scale farmers on 3.5 million hectares. Dogged issues around incapacity, corruption, knowing who exactly owns what land have been difficult to resolve. To address this, the government has recently appointed a new land commission to audit ownership and productivity.

Initially, the dramatic reduction and change in forms of agricultural production saw the worst affected areas producing as low as 30 per cent of potential. Over time, as farmers and government alike gained in experience, expertise and capital, the picture changed somewhat. In 2016, government rolled out Command Agriculture, an import substitution programme that saw resettled farmers, such as those on Bob’s land, contracted for a certain number of hectares and agreed to sell at least five tonnes of maize per hectare to the Grain Marketing Board (GMB). In return, government provided seed, fertiliser, and, where possible, tractors and fuel for ploughing. The cost was deducted from the maize sale price. Together with good rains, the programme was instrumental in ensuring that in 2017 farmers managed the highest productivity in two decades, with 2.2 million tonnes of maize.

Although it is only 18 km long, the dust road following an unmarked turn-off on the Chivhu-Nyazura highway that leads to my mother’s rural home in Gandiya village takes a long time to negotiate, winding through the former mapurazi (farms) once referred to as kwaDekoko, kwaJosiasi, kwaBhirijhoni, and finally kwaJhani. Now that commercial farmers de Kock, Josias, Viljoen and Jan are no longer there, the roads are not graded as frequently.

Gandiya village is located in Manicaland Province, in a region with very low temperatures, high rainfall and high elevation – best for tobacco, coffee, tea and horticulture. The ancestors of the people of Gandiya originally settled 40 km away in the Mwenje area. They were pushed out to the present reserve, a valley sandwiched between prosperous white-owned commercial tobacco farms.

These farms were underused, an affront to the villagers on crowded reserves. My mother often speaks of how her grandfather, Sekuru Killion Chiganze, was in the habit of taking his large cattle herds to graze on the white fields in the middle of the night.

Despite being forced into an arid, rocky, unfertile valley, the people of Gandiya village managed to farm mostly maize, beans and finger millet, which they supplemented with citrus fruits, groundnuts, sweet potatoes, vegetables and tomatoes. They sold to small grain dealers such as Harry Margolis, who grew his small corner dealership in Nyazura township, buying peanuts from the area, to become the present-day Olivine Industries, part of the Cottco Holdings Limited group, listed on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE). Later, these farmers would sell their maize, beans and finger millet to the Grain Marketing Board (GMB) in the town of Rusape, around 40 km away.

When the liberation war spread to this area, many of the villagers supported the fight for the return of their ancestral lands. The liberation movement’s political leaders and comrades alike, often referred to as vakoma (older brothers),defined themselves as vana wevhu (children of the soil). Writing in Roots of a Revolution (1977), Zimbabwe African Nationalist Union (ZANU) founding president Ndabaningi Sithole declared: “The black man belonged to the Soil by right of birth. He belonged to it by right of death as well. To deprive him of it was to rob him of his birthright and his death right! The Soil possessed him by right of his many ancestors who had lived on it and who had been buried in it. The Soil gave him life, and when that life left him, it claimed him back. He came from it and therefore he belonged to it. No one comes from where he does not belong. At death he returned to it. No one returns where he does not belong. He is the Soil in life and death – ‘Mwana we Vhu’, ‘Child of the Soil’.”

Naturally, identifying with this struggle for the return of their soil, the Gandiya villagers collaborated with the comrades in acts of sabotage on Dekoko, Josias, Jan, Bhirijhoni’s lands. As the war “got hot”, the farmers, including one General Wickus de Kock, a former Rhodesian Minister of Security who had fallen out with the government, abandoned these farms. My uncle, Sekuru Ben Chiganze, a young boy at the time of independence, recalls, that at several night vigils they would sing “VaMugabe tipei mapurazi tirime nyika yaayedu” (Comrade Mugabe, give us farms so that we can plough, the land is now ours). Self-determining as they now were in their newly freed country, many Gandiya villagers did not wait for Comrade Mugabe and took to “self-provisioning” Dekoko, Bhirijohni, Jan and Josias’s abandoned lands.

Soon after independence, as my grandmother, Mbuya Beneta Chiganze, recalls, her oldest brother-in-law, Sekuru Dickson Chiganze, a successful businessman in his day, who had worked in Zambia, came to tell her: “Mainini, huyai tiende ku mhinda mirefu” (Sister-in law, come and let’s go to the wider lands). My grandfather, a primary school teacher, was away at the mission, so she accompanied her brother-in-law and his wife. Weighing the distance from her current homestead, and the effort required in the new war of conquest for the best land, my grandmother decided to stay put in the reserve. For his part, Sekuru Dickson, having secured a portion of Bhirijhoni’s abandoned lands, would eventually acquire the nickname Mudhara Bhirijhoni (Old Man Viljoen).

The emergence of self-provisioning villagers such as Mudhara Bhirijhoni coincided with the post-independence government’s early redistribution programme, which operated within the Lancaster House agreement’s willing-buyer willing-seller framework. In the early land reform programme, planning usually preceded settlement, but in Gandiya village’s case, government rationalised their self-initiated land reform after occupation. Unsurprisingly, about 81 per cent of land redistributed during the 1980s was acquired during the three years following independence. The large tracts of land abandoned during the liberation war constituted the bulk of resettlement land. Where some previous owners, who had long abandoned their farms, later returned to lay compensation claims, this was done without delaying the redistribution programme’s planning and placement.

The early land reform programme initially aimed to resettle 18, 000 families on 1.1 million hectares over three years. In 1982, this was revised to 162,000 families on 10.5 million hectares in 12 years. By 1989, 52,000 families, representing a total of 420,000 beneficiaries, had been resettled on 2.8 million hectares on a voluntary basis. With 68 per cent of families yet to be resettled, the pressure for land remained.

Throughout the 1990s, pressure on the post-independence government mounted as it implemented the World Bank-driven Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP), which saw unemployment and inflation rise as per capita income decreased from US$645 in 1995 to US$437 in 1999. National and rural income inequalities deepened, as the rural economy suffered de-industrialisation. An increasingly agitated constituency of war veterans, restive rural communities, local politicians and black businesspeople continued to pressure government to use its two-thirds majority to radically transform the agricultural sector. During this period, government frequently clashed with communities that “self-provisioned” and occupied land.

The year 1997 was a defining year. As government attempted to speed up redistribution through the expropriation of 1,471 farms, Britain’s new Labour government announced that the former imperial power had no historical obligation to support Zimbabwe’s land redistribution. In response, Robert Mugabe warned at a land donors’ conference: “If we delay in resolving the land needs of our people, they will resettle themselves. It has happened before and it may happen again.”

By the 2000s, the war veterans were fed up with the ZANU–PF’s refusal to take over land. As a protest against their landlessness, the war veterans orchestrated a campaign over one Easter weekend, at which time 170,000 Zimbabwean families occupied 3,000 large white-owned farms. Initially opposing the move, the increasingly unpopular government backed the war veterans, sanctioning what Zimbabweans refer to as jambanja (chaos), that would characterize the fast track programme’s initial stages. In Gandiya village, the only beneficiaries of the fast-track program were three former freedom fighters who do not live in the village permanently anymore. Nonetheless, the new programme’s renewed focus on small-holder farms and the push toward forex-earning cash crops like tobacco would have important consequences for agricultural production in the area.

It’s almost dark when we stop at Mudhara Bhirijhoni’s homestead. The power is out, so he and his wife are already sleeping. But hearing that his late brother’s daughter and her family have arrived, he doesn’t mind the disturbance and receives us in their main dhanduru. In conversation, he is sure to remind us of his award as the best farmer for the 2015-2016 agricultural season in the annual five-ward field day organised by the Kumboyedza group, a local farmer’s cooperative initiated by my uncle, Sekuru Ben Chiganze. Bhirijhoni has won in this and many other agricultural field days over the years, the most recent one at the age of 90. He is remarkably sharp and fit.

A few weeks later, my aunt Mainini Foro Chiganze and I return to visit. Earlier in the morning we had called him to say that we would stop by, but when we arrive after mid-morning, he is not there. His wife, Mbuya Miriam, informs us that he has long gone to his fields. When we find him, he is weeding his fields with his hoe. Despite the late coming rains, his green maize stalks tower over his figure. We climb over his neat counter ridges; he shows us where wild pigs are starting to dig into his ripening fields.

Mudhara Bhirijhoni is part of the older generation of Gandiya villagers who have kept or are resigned to growing maize for their own consumption, either because the labour for crops such as tobacco is too onerous or because the GMB has become an unreliable buyer since the dollarisation of the economy. In the past, the GMB, which was opened up to black farmers at independence, provided a guaranteed market for farmers, but was not transformed to accommodate small grains and continued to use the Rhodesian institutional framework skewed in favour of cash crops, such as tobacco, cotton, maize, wheat and soya beans, all of which are more susceptible to droughts and can only be stored for a limited number of years. With the exception of sorghum, the GMB rarely buys the small grains that yield better harvests in drought-prone areas such as Gandiya. The large white-owned seed companies were also reluctant to invest in research and development of small grains. As a result, the first 10 years of independence saw the steady decline of small grains, such as finger millet, which are more drought resistant and can be stored for up to 25 years.

Nonetheless, Mudhara Bhirijhoni remains a successful farmer, true to his surname, Chiganze, which is a relatively recent adoption. It was the nickname given Sekuru Killion Chiganze, Mudhara Bhirijhoni’s father and my great-grandfather. It comes from the word kuganza (to show off). My great-grandfather loved to boast about his unprecedented success in farming. It made him wealthy enough to support three wives and many children, several of whom went to mission schools. When his sons were away working in towns and missions, he would supervise his daughters-in-law on the land. He was tough and known to have a temper, easily set off by perceived mediocrity from his immediate and extended family. So hard was he, that my uncle recalls a deep boyhood hatred-turned–admiration, because of his grandfather’s inclination to throw hardened soil crumbs at him for failing to lead the cattle properly during ploughing time. As people from the community and surrounding villages came to him for grain during difficult seasons, it was common to hear people say havaganzi mahara (they don’t boast for nothing).

We soon set off for my grandmother’s house. The familiar sign ndapota vharai ghedi! (I am pleading with you, close the gate!)appears. The tall matriarch, Mbuya Beneta Chiganze, stands waiting to welcome us with my mother’s only sister, Mainini Foro. We have an early supper, of meat, vegetables and sadza rezviyo (stiff porridge made from finger millet which Mbuya grows and grinds herself). I sleep with Mbuya and Mainini Foro. On Christmas morning, I am surprised – and quite relieved – that we only wake after 5 am. My 80-something grandmother is notorious for waking up at 4 am with the first cock crow. You will be woken up to the sound of her loud talk with Mainini and her beginning to go about her business, getting ready to go into her field by the time the sun rises. Sure enough, we are soon outside sweeping Mbuya’s yard.

My grandmother has been a winner in the annual five-ward field day’s category for widows several times. It is a category that she and some other widows campaigned for, complaining that their efforts cannot be compared to those of younger married couples. For help, she sometimes hosts a nhimbe (a work party) where food and, in the past, beer is served to the community invited to help with weeding, harvesting, and sometimes pounding, in return for goods such as soap, oil and other staple groceries.

After breakfast, we spend the morning visiting relatives in the village. It is Christmas day, but a few farmers, like Sekuru Aaron Chiganze, Mudhara Bhirijhoni’s son, are in their fields. He is part of the generation of young adults in Gandiya village who from 2000 onwards switched from maize to tobacco farming, as tobacco became an increasingly fashionable crop. Given that it is highly labour–intensive, tobacco appeals more to young adults. As a result, many young people, often jobless in urban areas, have returned to the rural areas to try their luck with tobacco. Many of the new tobacco farmers often boast that fodya igoridhe (tobacco is gold). Tobacco is an aspirational crop. Many of the Gandiya farmers have memories of the commercial success enjoyed by tobacco farmers Jan, Josias, Bhirijhoni, and Dekoko. Some now declare that they too have “arrived” as tobacco farmers, “tisu tave mabhunu acho” (We are now the new boers).

In his homestead, Sekuru Aaron has a scaled-down version of the large dhirihori (drying halls)that towered in Jhani, Josiasi, Bhirijhoni, and Dekoko’s fields. Sekuru Aaron shows us his structure as he explains the intensive curing process, which requires a continuous inferno for long periods of time. He explains how he must wake up every three hours to keep his fire going or risk compromising nine months of hard labour. Feeding the fires of these dhirihori has seen the deforestation of the surrounding woodlands, despite the eucalyptus seeds offered to small farmers by merchants and the Zimbabwe Tobacco Association (ZTA).

Over the years, several Gandiya farmers have complained about being ripped off at the auction floors. According to my uncle, at least three Gandiya tobacco farmers literary collapsed after their crop was auctioned for a song. Nationally, this experience was not uncommon at the beginning of FTLRP. The industry saw an influx of new, inexperienced farmers who suffered low quality and low yields. In 2008, the annual crop reached a record low of 48 million kg. Over the years, yields have since increased steadily as the ZTA and the Tobacco Research Board (TRB) channelled money into education and provided seed and equipment packages to small farmers.

By 2013, the industry had turned a corner. Zimbabwe is now producing 200 million kg per year, a level matching the pre-fast-track days. In 2016, Zimbabwe’s tobacco brought in US$887 million. At 31 per cent of Zimbabwe’s total foreign revenue, it is the country’s single most valuable export. This wealth is no longer the preserve of 1,500 mostly white large-scale tobacco growers. It is now generated by 100,000 growers, of which 70,000 are small farmers. For the average small farmer in Gandiya village, the auction floor income can range between US$2,000 and US$5,000. This is in a country where most people do not make more than US$100 per month, and in a village where few people have more than US$2 a day to their name. In good years, the most successful farmers are able to buy cars, new farming implements, and send their children to school.

While visiting my grandmother’s zviyo (finger millet) fields a few weeks later, I meet Olivia Muza, the local mudhumheni. Literally translating as “door man”, a dhumheni is an Agriculture Technical and Extension Services officer who goes from door to door, demonstrating best agricultural practice on individual farms. Mudhumenhi Muza is one of two Agritex officers in the area. With the responsibility of supervising over 771 families, more than the 400 families recommended by the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural organisation (FAO), her efforts are spread thin. The dhumheni who supervise nearby resettlement schemes supervise about 500 families, because they have bigger plots of land.

Mudhumheni Muza is not a big fan of tobacco: “When the farmers tell me they want a field day for their tobacco, I tell them that if they want it, they are free to speak to the other dhumheni.” As we give her a lift back to her home in nearby Rukweza village, Mhudhumeni Muza laughs, shaking her head as she talks of the “miracles” seen at places like Boka Tobacco Auction Floors, one of Harare’s three main auction sites. “Ha, you’ve never seen anything like it. Ladies of the night. Fake car dealers. Hoarders of trinkets which have absolutely no use. Everyone is lined up to make money off of these farmers who have never seen so much money before. Ha, especially in those first years, all of their money was finished at the auction floors.”

As she further explains, it’s not so much this that concerns her, because many farmers have learnt their lesson. It’s more that, between planting and auction-floor sale, many farmers go hungry as they haven’t planted any food crop and the previous year’s tobacco income is often inadequate to cover their food needs for the whole year. The situation is exasperated as the income from the leaf can vary greatly depending on supply of the crop at the auction floor and the quality of the farmer’s leaf. In the case of the latter, the quality is often affected by rainfall, the farmer’s inputs, and their curing and handling techniques. Mudhumheni Muza complains that their dhirihori are too small and that they squash their tobacco in rooms that are also too small. Compounding this, without the storage capacity to withhold their crop when auction floors offer unfavourable prices, farmers are often forced to be price takers. To assist farmers, the ZTA, along with merchants, are trying to get rocket barns on to all farms. These require less firewood and produce better quality crop. To help improve yields, they’re also rolling out a “pay as you plough” tractor hire scheme.

On the same day that I meet Mudhumheni Muza, I find Sekuru Aaron in his tobacco fields. I’m taking pictures of his fields, beautiful as they are, nestled in the Nyahwa and Nyakuni mountain ranges. I’m focusing my camera on the brilliant green of a particular leaf, when I hear Sekuru Aaron’s voice chastising me for taking pictures without letting him know. With his lean frame dressed in a green soccer supporter’s shirt, I had missed him as he bent over to inspect his leaf. He makes his way from the field to the dust road where I stand in the unrepentant heat with Mbuya, Mainini, and Mudhumeni Muza. Even with a hat, I don’t know if I can stand it for any longer. A sweat breaks over Sekuru Aaron’s brow. It’s hard work, and he is clearly tired as he greets us. He nonetheless manages a smile, clearly proud of his work. It doesn’t seem that he’ll stop growing tobacco in the foreseeable future. Putting aside her disdain for tobacco, Mudhumheni Muza offers him some advice on how best to cure what looks like a good crop.

In mid-February, 2018, my uncle, aunt and I drive around 180 km north-west of Harare, to visit a relative who has taken on a resettled farm about 20 km outside the farming town of Karoi. When we stop for refreshments at the OK supermarket in the farming town of Chinhoyi, my uncle meets an old acquaintance. He has moved permanently to a nearby A2 farm and, judging by the enthusiasm with which he discusses his farming, appears to be doing well.

The Sekuru we are visiting in Karoi is a former war veteran who settled full time on his medium-sized farm in the 1990s. He is even more enthusiastic about his new life as a commercial farmer. I have lost count of the number of times I have been told, both by Sekuru himself and other relatives, that it’s really worth paying his farm a visit. And with good reason. As you near his farm, a full-to-capacity dam appears in the distance. It services his and several other resettlement farms in the area. The farm has tall green maize fields. There are too many other crops to count. The compound he has built, following the neo-traditional style, is stunning. The several dhandhuru are tiled, the master bedroom with a built-in bed. There are two large, round kitchens, one for cooking, and one for dining. As we sit in their well-appointed dining kitchen, we are almost embarrassed as his wife presents us the elaborate meal she has prepared – sadza rezviyo, chicken stew, sugar beans, rape, okra – all from their land. When we leave, their family struggles to carry and load the double cab with the produce they have brought for us to take home.

As we return to Harare, I try to press my uncle, a retired businessman and A2 farmer, on his view of land reform success. Eventually he offers: “It really is a mixed bag. It depends on the area. It depends on the farmer. Some are doing incredibly well. Some are doing badly. The yields are not as great as in the past. But overall productivity is improving.”

I bring up Mudhumheni Muza’s view on the social cost of tobacco farming. My uncle is not too interested: “Look, Muza is now doing more than agricultural work and extending herself as a social worker. Here, I am only concerned with the economic aspect of things.”

In many ways, I believe, the very failure to think more holistically about land reform and what it means for social relations has created a situation where many women have been left behind. In 2000, at the commencement of the fast track program, 81 per cent of women and 58 per cent of men were engaged in Zimbabwe’s agricultural economy. And yet, while national figures are inconclusive, it would appear that the vast majority of resettled farmers are men. The few women who have benefitted in their own right are largely ex-combatants turned civil servants who were able to use their relative privilege to access land. Government later tried to address some of the issues facing women’s access to land with the introduction of joint naming of spouses in offer letters for A2 farms. This still did not address the problem, particularly in communal areas where women are subject to the old colonial and patriarchal customary law.

In thinking about my grandmother Chiganze, I am inclined to think that there are parallels between her decision not to claim new lands, even after her brother-in-law had called on her and the fact that her situation as a widowed woman had not been considered in the field days assessments. Both of these I believe, are reflective of the broader ways in which African women are often erased in our imagining of land and liberation. The patriarchal politics of land is consistent with what Horace Campbell calls the “patriarchal model of liberation”. The stunted vision of land is not limited to political leaders. It is after all the small farmers of Gandiya village who boast “tisu tave mabhunhu acho” (We are now the new boers). For all our aspirations towards African liberation, our imaginations often remain beholden to symbols of colonial patriarchal success. In many ways, the soil’s return has been a painful experience. In just as many ways, it has been a heartening one. Without a doubt, land reform has driven an unprecedented transformation of an agricultural system built on the unjust conquest of Zimbabwe’s land and people. It has radically changed who can be a farmer and how farming can be practised. As an African woman, who stubbornly holds on to her birthright to the soil, I can only hope that time can help us rise above those limitations in our visions of humanity and liberation.

In commemoration of our 20th year, we will be digging through our extensive archive.

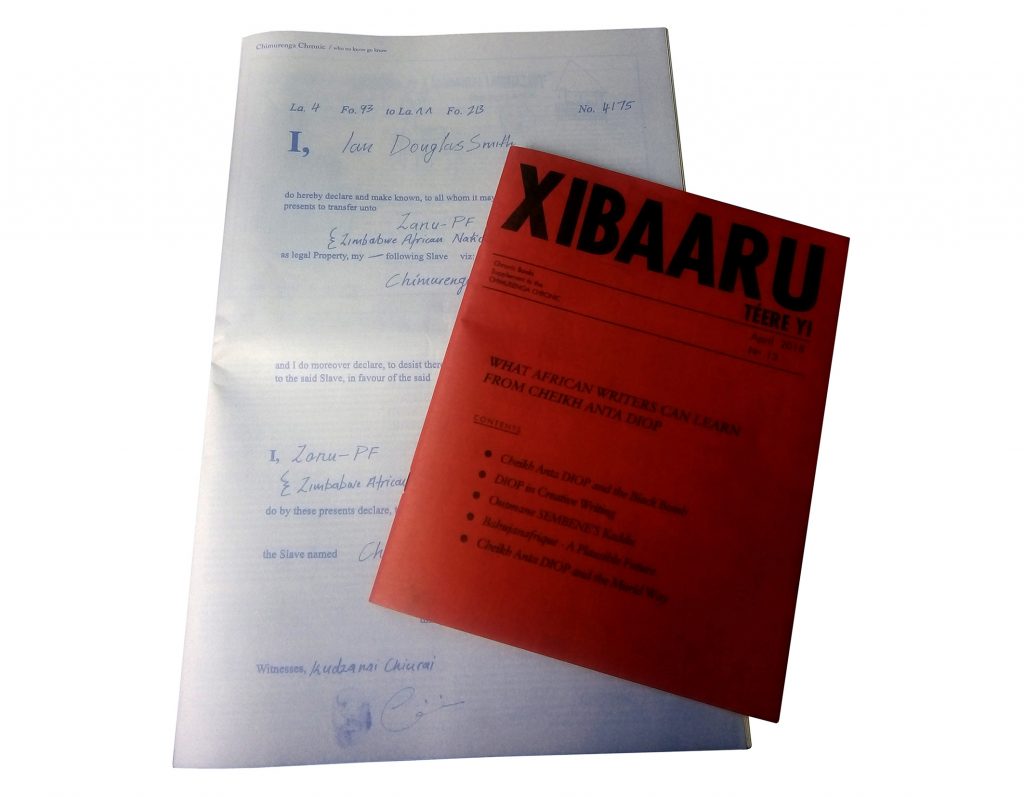

This story, and others, features in the Chronic: The Invention of Zimbabwe (April 2018). The events of 14 November 2017 in Harare, Zimbabwe form the backdrop of this issue, bringing together voices of journalists and editors, writers, theorists, photographers, illustrators and artists from the country to tell a different story of Zimbabwe, now and in history, and to dream new futures. The accompanying books magazine, XiBARUU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work