by Marissa Moorman.

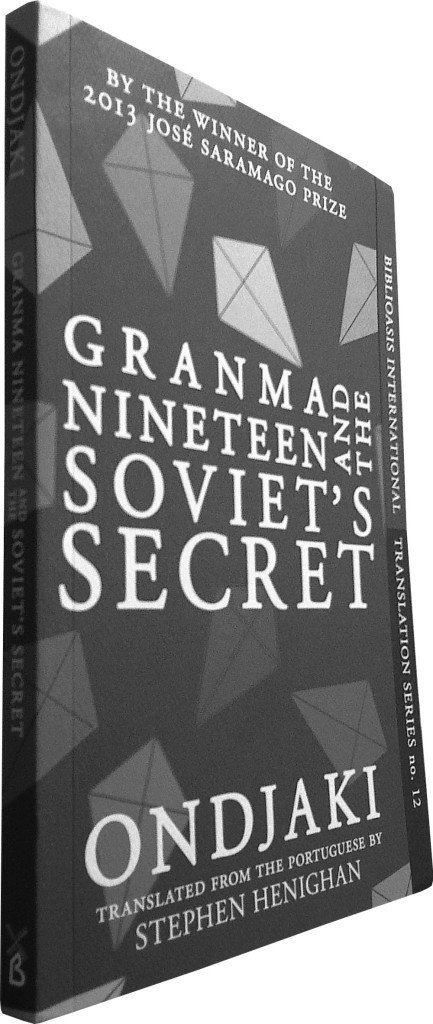

Ondjaki (transl. Stephen Henighan)

Biblioasis, 2014

An Angolan friend of mine refuses to read Ondjaki. He says the writer’s work is nostalgic for the socialist period – times he’d rather forget. I disagree.

Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret is the third book (and the second translated into English, following Good Morning Comrades) that uses a child narrator to reveal daily life in 1980s Luanda. It tells the story of a group of children and their plot to “dexplode” the mausoleum the Soviets are building to hold the embalmed body of Angola’s first president, Agostinho Neto, in the ocean-side neighbourhood of Bishop’s Beach.

No treacle here. Rather, it is a world remembered and re-imagined to different ends: a land of counter-factuals. The epigraph from Clarice Lispector is apposite: “[…]blue because the dusk may later turn blue, pretending to suspend feelings from golden threads, pretending that today childhood is gilded with toy shops[…]”. Invoking the intimacy of colour and sentiment, memory the launching pad for make-believe.

The book opens (and closes) with an explosion. In the “yellow mixed with red pretending to be orange in a bluish green” of “that explosion in Angolan colours at the Soviet construction site” we are far from the red, yellow, and black of the Angolan flag and the ubiquitous grey that those of us who grew up in the West during the Cold War imagined prevailed behind the Iron Curtain, if not in all socialist states. The children’s palette is not polemical.

The militarisation of society under civil war, socialist etiquettes, and geopolitics echo and trill in snatches of conversation, linguistic play and parrot echolalia: “The parrot His Name shouted out to expose us: ‘Down with American imperialism.’ We made an effort not to laugh: the words came from a television commercial that hadn’t run in a long time. Just Parrot finished off: ‘Hey, Reagan, hands off Angola.’” Or from the neighbour, Sr Tuarles, when he demands: “Hand me the comrade paint thinner. And not a peep, or I’ll go get my AK-47.”

The shape of life at Bishop’s Beach ripples under this pressure as the narrator, his sisters, cousins and friends (Pi – aka 3.14 – and Charlita) fear losing the neighbourhood to the plan to demolish local houses for the Soviet-built mausoleum. Deeper than the socialist solidarity threatening the neighbourhood, the narrator’s, Pi’s, and Charlita’s plot to “dexplode” the unfinished mausoleum resounds with a long history of cinematic exchange: Westerns (what the Angolans called “cowboiadas”) and the Spaghetti Western They call me Trinity, or Trinitá, locally. Dynamite, they know from Westerns, is used for blowing up trains. Why not a monument shaped like a rocket?

If you know anything about Luanda these days, probably it’s that the price of anything is astronomical. From housing to a melon, cars to footwear, Luanda challenges the budget of the humblest and the least so. Socialist monikers are quaint and jocular linguistic relics in an urbe obsessed with hierarchy, thick with construction dust, and vertically ascendant in glass and steel. Since 2002, the demolition of homes for new urbanisation projects and the “requalification” of large parts of the city have been remaking urban space in the political and economic interest of the ruling oligarchy. Excellent scholarly work has been done on these questions by Chloé Buire, Sylvia Croese, Claudia Gastrow and António Tomas.

Granma Nineteen is not about this. But it captures a moment in the 1980s that foresees some of today’s urban thunder. And in a way, it marks a turn in Ondjaki’s writing. Os Transparentes (published in 2012, and the winner of the 2013 José Saramago Prize) is a bigger, rangier novel. Ondjaki takes on Luanda’s current state frontally; his capacity to imagine characters, stories, sounds, and the use of the magic of Angolan language is in full effect. If you read Portuguese, read it.

Today, Ondjaki lives in Rio de Janeiro but visits Luanda regularly. In this Luanda, Bishop’s Beach is not only the site of the mausoleum, now completed, but also home to the new National Assembly, a mash-up of the US Senate building and the Blue Mosque, constructed by the Portuguese company Teixeira Duarte. Indeed, the little neighbourhood is nearly no more.

“I am a person who is increasingly attached to the past,” says Ondjaki in response to my questions on these changes. “I call this place ‘before’. I don’t think of this as a measure of time; I believe that it is a place. Sometimes, writing, especially as I write, I travel there. It is in the past that I feel best. My Praia do Bispo (Bishop’s Beach) is, therefore, one that no longer exists. I think that time passes and it’s natural that the present interferes in the architectural past of the city of Luanda. I think that there are modes of intervening that are more balanced than others. As a citizen, I would like it if the planning of our present and our future (I refer to Luanda) were more carefully and thoughtfully done.”

Since the civil war ended in 2002, several unfinished buildings and works have been completed, the mausoleum to Agostinho Neto among them. The Ministry of Justice is another. I first lived in Luanda in 1997, in Bairro Azul, the neighbourhood nestled up to Bishop’s Beach south, and I passed the mausoleum, its abandoned heights quiet in the morning’s red dust, as I tromped to the archives and interviews. At that time, rumour had it, that shifting local sand, which subtended shallow soil, was too unstable to anchor weighty Russian marble and finishing the mausoleum was physically impossible. It marked the failures of socialist solidarity, poor engineering and ongoing civil war that rent the nation. Seeing it completed might set something right.

“Maybe this work is part of a given historical moment and, sincerely, I think they did well in concluding it,” Ondjaki comments. “Since it was there for such a long time waiting to be finished. Since it was part of our imaginary as children. I think that with time it could become a ‘place of cultural practices’. This would make the most sense. We’ll have to wait and see what the future of the place holds for us. I hope to one day take my children or my grandchildren to the mausoleum to see theatre, opera, poetry, etc.”

And then, since I had asked so many questions about the city, space, people, but not the writing, I asked if he had anything to add about the history of Angolans with the Soviets (either as people or as states), about writing, or the city. He responded with this:

“I can say that this book, although it has features that are historical, or even anthropological (because it deals superficially with the Russian and Cuban presence in the city), was overall a stroll through the sentiments of my childhood. I have with this ‘Avó Agnette’ (better known as Avó Nineteen) a deep emotional and educational relationship. I typically say that I learned much about literature with her, even though she’s not a writer. Because the notions of time and space, the silences and rhythms of a narrative, the contours that hide and the curves that one chooses to say, all that came from many hours of conversing with her. I learned to read some of life’s maps also with her. This grandmother, with a generous openness, gave me a geography of times and affects that came from her tales and that were shown to me, late at night, like giant holograms where it was necessary to learn to read. And slowly, she gave me the codes, some of the secrets of the unfolding of time; the delicacy of imagining a past more robust for those who had only shown isolated pieces of their lives; she showed me her circular mode of reading characters, the neighbourhood, the facts and loves that hadn’t happened. I felt, at a certain point, that my imagination was being used as a laboratory by her, but at the end of the night, at the end of each conversation, in the reinvention of ‘a life story’, the result of those experiences was offered to me as an open and unfinished product. Little by little I understood what she said to me, slowly, that I should write in the way that made the most sense for my imagination and my sentiments. That is, she was teaching me the simultaneous task of looking at the world but writing with what was collected from inside me. These are lessons I cannot forget, nor refuse, because they are written on my skin.”

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop. Copies coming to your nearest dealer now-now. Access to the whole issue and Chronic online archives is available for $28 for one year or $7 for a month.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurenga-shop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button] [button link=”https://chimurengachronic.co.za/online-subscription” color=”black”]Subscribe to the Chronic[/button]