by Stacy Hardy

Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire and George Pompidou were friends at École Nationale de la France d’Outre-Mer in Paris. They were in love with liberty. They met in the library to read African-American poets of the Harlem Renaissance and French Symbolist poets.

Once president, Senghor began to build his own library – a giant structure containing all the knowledge of the black world: Maurice Barres, whose novel, Les deracines, about children defying their ‘civilising’ education first inspired him to write poetry; Baudelaire, whose mixed-blood West Indian mistress provoked him to write about contrasting cultures; volumes by Rimbaud; WEB Du Bois’s writings; Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau who he debated so furiously with Césaire; a signed edition of Jean Paul Sartre’s Black Orpheus; works by Césaire’s student, Frantz Fanon; novels by Mongo Béti, Cheikh Hamadou Kane and Ousmane Sembène; Wole Soyinka plays; communist pamphlets bearing the monogram, Bureau d’Éditions; editions of Recite du Monde noir and Revue du Monde noir.

It was the era of the great poet-presidents. Mao Zedong in China, Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam; Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, António Agostinho Neto in Angola and Rómulo Gallegos in Venezuela. Do poets make better presidents, asked Pablo Neruda. Or is it that presidents make better poets?

Neruda was never president. He stood down as a candidate in the 1970 Chilean elections to support Salvador Allende. Allende’s cabinet became his library – Neruda, Fernando Alegría, Eduardo Galeano, Eugenio González Rojas, Víctor Jara and Cecilia Vicuña being among his friends, advisors and ministers. His library was burned to the ground in the coup that put Augusto Pinochet in power.

During the hunt for ‘subversive elements’ under the military regimes in Argentina, Uruguay and Chile in the 1970s, hundreds of libraries burned. Three decades later, after American legions invaded Iraq, thousands upon thousands of books in the Library of Baghdad were reduced to ashes.

Throughout the history of humanity, only one refuge kept books safe from conflict: the walking library, an idea that occurred to the grand vizier of Persia, Abdul Kassem Ismael, at the end of the 10th century. He kept his library with him – 117,000 books aboard 400 camels, arranged alphabetically by the books they carried.

South African President Johannes Vorster had Steve Biko murdered for declaring black is beautiful. He then banned the children’s book, Black Beauty, for joining the same words.

President Daniel arap Moi of Kenya once banned a family planning book by the Girl Guides Association of America, calling it immoral. He also banned Marx and Lenin, and anything by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. But Moi could not imprison thought. The books invaded his brain. In 1986 he dispatched agents across the countryside to arrest the eponymous fictional hero of Ngugi’s novel, Matigari. When they found that Matigari was only a character, Moi ordered the book be arrested instead. Matigari was now only available in English and even then only outside Kenya. The book and the character had joined their author in exile.

Robert Mugabe spent his school days in the library. Books were his only friend, recalled a classmate. Years later, as neo-liberal reforms swept Africa, Mugabe again found himself alone in his library, books as companions: the complete works of Marx nestled up against Christian theology; a set of books by Gandhi, a gift from Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda. A special shelf was reserved for his one indulgence, Graham Greene novels.

Ho Chi Minh was thrown out of home by his father, a farmer who did not approve of his son spending his days in the library following intellectual pursuits. Later, Ho Chi Minh would be known to carry his books in his head, a library as reliable as the great archives of France, Germany and Russia, where he studied.

Thabo Mbeki built a library so large and complex only he could navigate it.

I am an African, declared Mbeki in 1996. My mind and my knowledge of myself is formed by the victories that are the jewels in our African crown, the victories we earned from Isandhlwana to Khartoum, as Ethiopians and as the Ashanti of Ghana, as the Berbers of the desert. Six years later, he travelled to Timbuktu to restore manuscripts and build modern libraries to house them.

The shelves in Fidel Castro’s library make no distinction between fact and fiction; various books on politics and philosophy, alongside novels by 19th-century Argentine writers and Italian science fiction. When the Batista coup took place in 1952 and many sat down to read Lenin’s What is to Be Done?, Castro dug out Curzio Malaparte’s Coup D’Etat: The Technique of Revolution, a novel that shows how a coup d’état might be a simple question of technique.

During the 2002 Venezuelan coup d’état attempt, Castro lent Hugo Chavez Malaparte’s book, so he could understand the situation and act quickly. Another book that found its way from Castro to Chavez was Don Quixote. Chávez so identified with the eccentric knight-errant fighting injustice that he had one million copies of Don Quixote distributed to Venezuela’s poor.

Chavez’s library lacked the grandeur of Castro’s, but not the content: The Turning Point by physicist Fritjof Capra, dropped at page 112, to be used in a speech to oppose a new US free- trade zone across the Americas; The Green Book by Muammar Qaddafi; The Hydrogen Economy by Jeremy Rifkin; a whole shelf for books by Simón Bolívar; another for anything on George Bush – Michael Moore’s Dude, Where’s My Country? being a favourite.

Bush was reading The Pet Goat to schoolchildren on 11 September 2001 when the second airplane hit the World Trade Centre. The Pet Goat entered the American curriculum after Bush mandated only scientifically based educational programs be eligible for funding. Its publisher, McGraw-Hill, subsequently made a fortune. McGraw-Hill CEO, Harold McGraw III, served as one of Bush’s advisors and its executive vice-president, John Negroponte, was ambassador to Iraq during Bush’s second term.

After Chief of Staff Andrew Card gave Bush the news, the President remained seated for several minutes listening: A girl got a pet goat. His face was blank, indifferent to everything that was happening. Bush’s personality lay unfolded: it contained nothing.

You are a donkey, Mr. Bush, said Hugo Chavez.

Angolan writer Jose Eduardo Agualusa once wrote a novel about a genealogist who sold the country’s nouveau riche new identities to hide their shady pasts and profit from the future.

Soon, Agualusa was contacted by a high-ranking official in the government of President José Eduardo dos Santos. Would he, the official asked, be interested in ghost writing biographies for the state?

President Goodluck Jonathan’s library is empty, complained the Nigerian people. The press regularly pointed out that an earlier generation of Nigerian politicians read and wrote avidly. Obafemi Awolowo, it was said, read and wrote more books on Nigerian politics than most professors of political science. In 2012, Jonathan, tired of his literary habits being a point of derision, roped in Wole Soyinka and launched a nationwide Bring Back the Book Campaign.

But, asked poet Niyi Osundare, where did the book go in the first place? Was it sacked? Excommunicated? Set ablaze? Or did it just walk away on its own having found the Nigerian environment hostile and life threatening, especially in those dark and dreary days of military dictatorship?

A year later, the book is still not back and the shelves in Jonathan’s great library stand empty.

Stacy Hardy‘s story was originally published in the August 2013 edition of the Chronic.

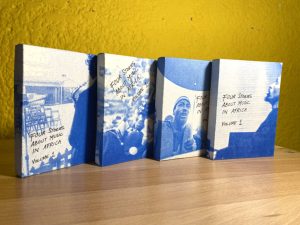

The issue also features reportage, creative non-fiction, autobiography, satire, analysis, photography and illustration to offer a richly textured engagement with everyday life. In its pages artists and writers from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states. Available in print or as a PDF.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/product/the-chronic-august-2013-2″ color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button]