by Moses Marz

Elected four times as mayor of Palermo over a period spanning more than 30 years, and holding various posts as public servant and European statesman in between, Leoluca Orlando’s first political opponent was the mafia and its affiliates in the Italian political establishment. When his former friends and fellow anti-mafiosi Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino were assassinated in 1992, everyone thought Orlando would be next in line. He was affectionately called il morituro, the walking corpse, by the people of Palermo. With their support, particularly support from women and the youth, he managed to first rid the city of the taboo of speaking about the mafia, and slowly regained control over the city, house by house and street by street.

Mayor Orlando’s reputation as a fearless anti-mafia fighter was rarely questioned until, in the late 1980s, the Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia, in a Corriere della Sera newspaper article, dismissively referred to Orlando and Borsellino as “anti-Mafia professionals” shortly before his own death. Sciascia claimed that the mafia was content to play along with what they perceived to be show court trials organised by Orlando, serving as effective cover for their general change in strategy. In fact, in the 21st century the Sicilian mafia, Cosa Nostra, was still alive and well, even after Orlando had announced his victory in 1999. By then the mafia no longer claimed as many lives as it had in the previous two decades, where the body count reached levels comparable to the conflicts raging in Belfast and Beirut at the time. The mafia had effectively been driven out of local government structures—leaving Palermo open for business with the globalised economy, and for hundreds of thousands of tourists arriving on cruise ships every year—but it still thrived in the world of business. Going with the times, Cosa Nostra teamed up with the Nigerian mafia on the trafficking of heroin and sex, while they themselves specialised in dealing in weapons and human trafficking.

Throughout these internal transformations, immigration never featured as a prominent issue in the mayor’s political life. Palermo, at the centre of the Mediterranean, had for centuries been a crossroads for cultures from across the world, who lived side by side without attracting much attention. This was to change when the so-called “European migration crisis” reached Sicily in the aftermath of the assassination of Libya’s president, Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. As Gaddafi had prophesised, his removal effectively opened the Libyan ports for travel across the Mediterranean. In the following years, half a million migrants passed through Palermo, a city with barely more than half a million inhabitants. In the summer of 2018, the crisis hit fever pitch and the mayor’s reputation and power was put to test. The Aquarius, a ship carrying 629 migrants who had taken the route through Libya, was approaching the harbour of Palermo requesting permission to dock. Matteo Salvini, Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister from the right wing party Lega Nord, who had been voted into power the same year as junior partner in the Five Star Movement’s three-party-coalition, announced that the Aquarius should be sent back to Libya if none of the other EU countries was willing to take in the migrants. Following Salvini’s announcement, the conflict among European heads of state reached levels not witnessed since three years prior, when Germany eventually granted millions of Syrian refugees asylum in violation of the already-defunct Dublin Convention.

In defiance of Salvini’s order, Mayor Orlando went on national television and declared that, “Palermo in ancient Greek meant ‘complete port’. We have always welcomed rescue boats and vessels who saved lives at sea. We will not stop now.” Along with Domenico Lucano, the mayor of the small town of Riace in the neighbouring region of Calabria, Orlando had earned a reputation as among the most outspoken opponents of the xenophobic discourse upheld by European states. In the Charter of Palermo in 2015 he called for the abolishment of the residence permit and for the recognition of mobility as a human right. His practice of personally welcoming new arrivals whose boats were rescued or intercepted by the Italian coast guard, and symbolically bestowing on them the civic status of Palermitans, was viewed as heroic by a section of the European left, but could be dismissed by a larger audience as eccentric and utopian. The brief showdown between Salvini and Orlando underlined the fact that the mayor’s actual realm of political influence did not even include the harbour of his city. The Aquarius was denied entry and had to travel another 1,296km to the coast of Spain before its passengers were sent to France following an offer by President Emmanuel Macron.

In an atmosphere of defeat and renewed urgency, the mayor was invited to deliver a speech at the Teatro Massimo as part of the official opening of an art biennale hosted by the city. Orlando was not the only one to speak that evening. The organisers had invited an academic and an artist from New York and Paris respectively to speak to the biennale’s theme of “Planetary Garden—Cultivating Coexistence”. An admirer and supporter of the arts, one of Orlando’s favourite analogies of the importance of synchronicity between citizens and society in the fight against organised crime, was the two-wheeled Sicilian chariot—with one wheel representing the law and the other culture. Given his stance on what he called “cultural contamination” the mayor’s endorsement of the biennale, and vice versa, worked on several levels. The Teatro Massimo provided a fitting stage for the event. Considered as one of Europe’s finest opera stages at the end of the 19th century, the theatre had fallen into disrepair in the decades in which the mafia gained total control of the regional government of Sicily. In 1974 it had to close for reparations that ended up taking 23 years, with most of the money re-directed to corrupt politicians. It was only in 1996, in Orlando’s second term as mayor, that the theatre was reopened with the gilded frieze over its main entrance declaring: “Art Renews the People and Reveals their Life”.

Its five stories of opera galleries, decorated in gold and with a round glass ceiling depicting a biblical scene, looked imposing as the hall filled with international visitors of the biennale and Palermitan activists who had staged a demonstration in the city centre the night before against the fate of the Aquarius. The atmosphere in the hall was sombre, yet expectant of how the mayor would respond to the defeat at the hand of the government in Rome. The international guests were asked to address the theme of the biennale. They spoke about the inherent human desire to move and offered several personal anecdotes about their own migration experiences, which led to a call for solidarity and openness towards strangers. Apparently upset with the superficiality of their remarks, the audience grew increasingly impatient during their conversation. From the back rows a voice shouted, “Enough! We want to hear the mayor!”—a demand that was supported by clapping hands among others in the audience.

When the mayor finally took to the stage he was visibly exhausted from the recent events. But when he started speaking, none of the tiredness could be seen. Once again, he proved his ability to win over his audience with his sense of purpose and immunity to admit defeat which had over time turned him from il morituro into il presidente for the people of Palermo. “Migration can no longer be considered as a problem of borders, be they cultural, religious or identitarian, problems of social policy or access to the labour market”, he began. “The logic of emergency and the policies that have lasted for decades must be left behind! Human mobility should be appreciated as a value in and of itself, a resource, and not a burden for any country.” There was loud applause. He attacked what he called Italy’s “creeping economic racism” that cynically denied migrants entry, while at the same time maintaining a system of neo-slavery on the plantations of southern Italy, before turning to the bickering among European politicians about accepting a few hundred migrants.

“Do you think that among 600 million Europeans there is not enough space to accommodate 500,000, one million, two million, 50 million immigrants?” He laughed and shouted, “Of course there is!” After a brief pause to allow for the noise in the audience to taper off he continued: “They speak of economic migrants as if they do not have the right to asylum. What does that mean? Are they saying that it is not okay to die when there is a war in your country? But if you are dying of hunger that is okay? That does not make any sense! Abolishing the residence permit is our only possibility of building a new citizenship, one that is based on sharing, reciprocity and mutual respect, on implementing policies of empowerment and autonomy!”

After an even louder applause he ended his speech saying, “I have survived the war against the mafia and I have won. I will also win this war even if it shall not be in my lifetime. I have seen what the future looks like. It looks like Palermo—like a mosaic, not a painting. And as the mayor of Palermo it is my privilege and honour to welcome you all to this beautiful city. You and I, we are all Palermitans!” There was a standing ovation when the mayor came down the few steps from the podium. A small crowd of visitors and journalists had gathered to speak to him, and he obliged them smilingly. That is when shots were fired from one of the opera lodges. The two body guards standing behind the mayor were caught off-guard. The mayor was hit and died almost instantly. The assassin was never found.

The news of how the mayor paid the ultimate price for his ideals soon spread across the world and brought his project the attention it had never before received. Among the rumours on who was behind the murder, the most obvious candidates were right-wing extremists, potentially operating with the blessing of Rome and the Catholic church, as well as his old enemies from the mafia. Some analysts even went as far as speculating that the mayor had orchestrated his own assassination, considering how perfectly his death had been set in scene. They asked why the mayor survived all those years fighting against the mafia, while those closest to him had been eliminated. Was not the very fact of his survival making him suspicious? Have not all those who advocated real change been killed before they could reach their visionary goals? Was killing himself not his only way out before he would, sooner or later, betray the struggle for radical change?

On the night of the murder, the streets of Palermo swelled with people, in honour of the mayor’s life. Via Maqueda, the street leading to Teatro Massimo, was filled with mourners dressed in black, whose assembly drew lines from the theatre to the town hall behind Piazza Pretoria, and all the way down Via Vittorio Emanuele to the sea promenade, Foro Italico. In scenes reminiscent of the Egyptian Tahrir square demonstrations in 2011, the people did not leave the streets in the days and nights to come. What began as a mourning procession spontaneously transformed into a fully-fledged demonstration. The banners held up by protesters read “Global Apartheid Must Fall”, “Residence Permit = New Slavery”, “We Are All Palermitans” and “Let Mayors Rule the World”.

A few weeks into the protests, a camp at the sea promenade was set up and called Resurrection City in homage to the Poor People’s Campaign created in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jnr. What at first looked like a refugee camp, quickly turned into a breeding ground for a political movement that took up the mayor’s struggle for the abolishment of the residence permit. But judging it too moderate, they articulated their claims in more radical terms. The inhabitants of Resurrection City elaborated new concepts of belonging and being together that were informed by the experiences of migrants and social organisations developed in refugee camps across the world. Their calls for a “right to opacity”, “the abolishment of the integration paradigm” and “relational freedom” not only shifted the content of the debate around migration, but the very terms used in that conversation. Fearing that the mayor’s understanding of human rights would do little more than ensure a steady influx of cheap labour catering to the needs of an ageing European population, they advocated a different sense of justice, one based on the dictum “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am”. The sense of freedom growing out of this perception would be different from the personal liberty to do whatever one pleases; a relational kind that urges individuals to act responsibly in relation to their community and with an awareness of the interdependence of all beings.

At first the mainstream media tried its best to channel the movement in ways that would portray Orlando in a similar light to Angela Merkel, after her severe loss in the German elections in 2015. But once the protest in Palermo spread to other European cities, with the initial support of the mayors of Barcelona and Rotterdam with whom mayor Orlando had developed close ties during their meetings at the Global Parliament of Mayors, the movement developed a dynamic of its own. After initial resistance to what they dismissed as an impractical proposition, leftist parties and NGOs across Europe realised that this was their only chance of regaining a degree of relevance. During decades in which they appeased voters by pledging to fight for increasing levels of social justice that led them to endorse a nationalist agenda equal to that of their opponents, they were completely marginalised in the course of several elections.

Orlando offered a new vocabulary, a new historical framework against which it was possible to formulate claims for a different politics. It became increasingly clear that the city, not the nation state, would be the framework in which such a politics could be articulated. The nation state had worked well for promoting the independence of autonomous nations and individual freedoms. Its disposition towards the pursuit of selfish interests made it, however, unsuited to survive the age of interdependence. The city, as the place where pragmatism and creativity overruled ideologies of sovereignty and nationality, appeared to be the way out of the cul-de-sac in which the minority-majority dialectic of national democracy had led. What was called for was a return to the beginning of human civilisation, only this time not to Greece and its polis, but to the African villages from which the storytellers were never banished and palavers ended in consensus, or with the decision to dislocate and create new communities elsewhere.

The winds of change had already taken on the force of a tornado in the imagination of the people when several European nation states, following the lead of Portugal, eventually openly invited migrants to settle. The EU parliament passed a Structural Adjustment Program for itself—one that would provide migrants with the necessary infrastructure required to settle in Europe, further their education or continue the profession they had learned at home, and build communities that were in line with their ways of life. This, it hoped, would grant the international community a new lifeline. Too late. The nation state, once dismissed by a famous Nigerian writer as the greatest crime against humanity, should be no more. With the assassination of the mayor, its death-sentence had been pronounced.

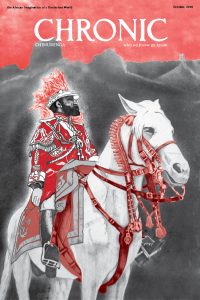

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[hr]