by Thabo Jijana

On December 13, 2016, in Salem Party Club v Salem Community, the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled in favour of 152 land claimants representing a community of amaXhosa who’d been dispossessed over a century ago by the 1820 British settlers and their descendants. While the court victory has been rightfully celebrated as a tentative triumph of South Africa’s processes of restorative justice, Thabo Jijana suggests that Salem Community v Government of the Republic of South Africa and others is also a seminal event in how it asserts the legal validity of oral history (as largely provided by the community’s witnesses) vs. documented proof (by the landowners).

To talk about death, Black rural grief … TO DEATH, putting into question colonial constructions of space, so metadiscursive whenever old memories resurface, ever drenched in exhaustion re: foiling the artifices of whiteness, the hail of not once yielding to the Lethe ruptured afresh, reflective nostalgia at high octane, the seeing of place a fundamental disruption of our ways of seeing, to expose that ideology to which much fart-puffing has been tithed, a furious binge ensuing for the untidy, esoteric spark of the anecdotal

, and that’s when I thought, in that anew-coiled moment of ah-hem, perhaps

perhaps

FORGETTING IS NOT THE PROBLEM but that where white is the colour

BLACK IS THE NUMBER

In recognizing the maneuvers by which Black rural bantu have found fugitive means to refute the immanence of forgetting, this must be said

: we are all forced to resituate Black death within a retropresent though still largely spontaneous sphere of memoir-realizing, by which we mean what defines our kin (to each her own, idiosyncratic as to the relational dot) decides how we greet their deaths … to treat dying as not only representational of the life histories we corroborate with our body language but as archival material resistant to the forces shoving their imperialist erasure down our throats, discrediting the settler value system inherent in historicizing rural people’s borderless movements … self-dossier-ing one’s life bedevils us to hang onto the explosive psalms of our everyday, tracking the hems of our being one remembered detail at a time, a lifetime of identity-making cut down to its minutiae …

What I am attempting to convey is the simple but heavy truth

that

BLACK PEOPLE ARE ALWAYS KEEPING SCORE

, especially in those moments when even statistics usher us, needle and thread, towards a necessary return to riddling narratives, those vain appeals that come again within your hearing and that we send away without having responded to them in their space, our space, the space that their passage describes, as if an imperious force dictated that the same figure be taken up again and again, that an endlessly new version of it be created, thus making sure, through the repetition of a model, a structure, a gesture, of the incessant reiteration of signs that trace faces and stories, A REFUGE AGAINST THE IRREVERSIBLE, better verbalized in the context of the unmitigated presence of death in rural communities such that recalling faces, names, quotables, locations, genealogies takes on a running commentary bar sustained depth

1. Rarely, as they did in my childhood, are heads of families buried in the familial yard, by the kraal these day

2. I hail from a Ciskei village of erstwhile farmworkers violently relocated from their original farmlands

3. In the fifteen years since my father died, I have visited his grave (by myself or otherwise) four times

4. 30 out of the 45 people who met their deaths in Marikana came from rural Transkei

5. Bestowed on my village recently was its right to ownership of stolen land

As in Salem Party Club and Others v Salem Community and Others (2017), in which Salem’s Black community, Tyelera, had the Constitutional Court uphold its right to ownership of land they were dispossessed of, Justice Edwin Cameron was quick to remind the 17 applicants opposed to the Tyelera community’s claim to the Salem Commonage

: Oral history is not only concerned with historical facts, but also the values and convictions of the community it recollects

7. Grace Nichols, probing

: How can I eulogize their names

What dance of mourning can I make?

8. A tangent on the grammar of this data, stretching my limits of coherence to say

: the informatics of Black death become the chains whose links often tie us into straightjacketed readings of this historiography of rural bereavement, predetermining the tone of our solidarity with unfamilial sorrow

9. In voicing the past, we look to rural rituals (and dying, as a critical life stage, comes with a plethora) as the most visible confirmation of the replicability of rural memory, if only to critique our strong tendency to rationalize dying as primarily existing beyond the phenomenal world

1o. 2:40-47 of Nomvula, the Freshlyground album where Zolani Mahola sings Yhini na bethuna usishiyil’ uSis’ Nono! Usishiyil’ uSis’ Nono!

Nomvula is not without tender moments describing the mourners’ behaviour; Zolani’s father did not weep at the burial, maybe incl. Zolani

: Zandl’ ezincinci zalahl’ uthuth’ eluthuthwini singasazi nesizathu

More a young girl’s unbelief at her loss than a rejection of the routine of mourning she is undergoing

In the way Mahola mouths her mother’s moniker, she near-plumps herself onto the words until they tumefy at the waist and an oval shape begins to form and just at the point of yielding to Ohhh finally the sentiment catches up with the curve of her lips and Nono deconstructs into No-noooo, No ohhhh

11. It is this manipulation of datum qua defying the threat of not remembering, memories piled upon memories, flashes of happiness upon blind spots and the promise sadly left unsaid, lamentations thrusting at me with their belligerent arrowheads still dripping with warm blood, which interests me

: Ukufa kudibanisa abantu

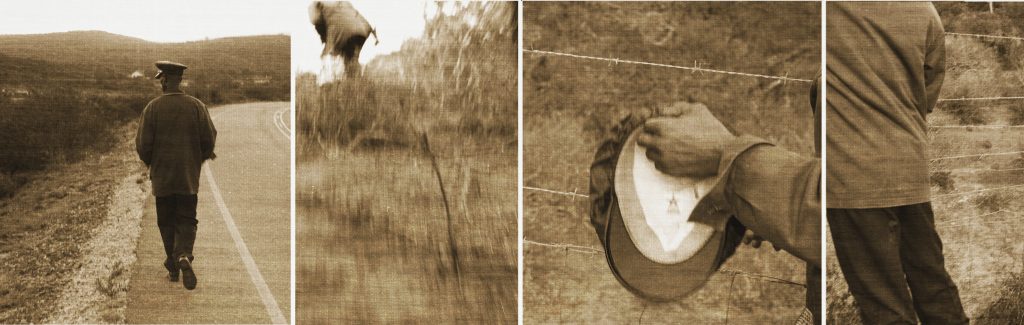

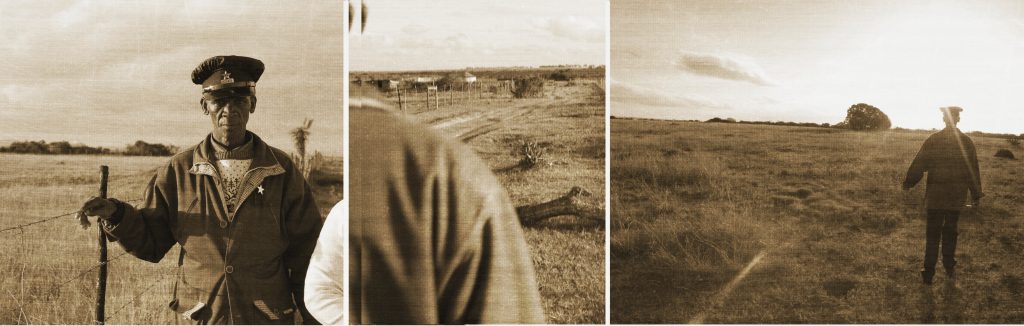

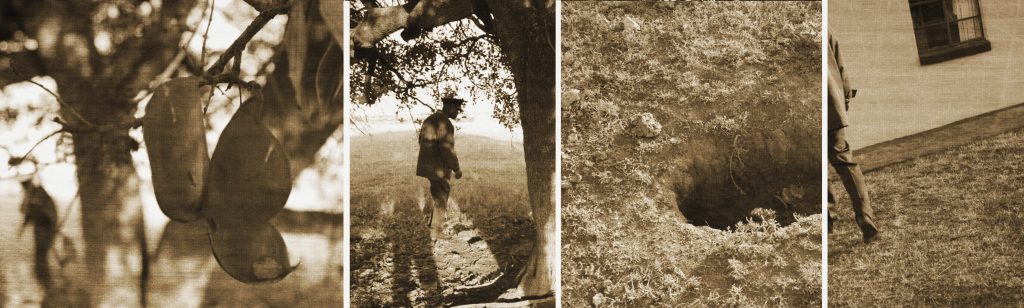

In Tyelera they took me to the old graves, some behind colonial-era buildings, others next to the R343 heading towards Kenton-on-Sea viz fleeing Makhanda, some so concealed within unpeopled forest and at such a commanding distance from where Tyelera’s present Black population resides only the lone daring hunter and village historian would remember the coordinates, wading for long stretches at a time through stubborn foliage and the tricky sideways gravel footing, my ZCC cap-wearing guide keeping his inferential talk going as he hand/foot-flicked one isiphingo branch after another ‘ntsinde shrub aside until we started running out of saliva and had to make do with our own private thoughts – Funisile Khathu took me to eMqwashini, on the Rippley Farm, belonging to a settler-descendant farmer who, Khathu knew in no uncertain terms, would grant us access on any day and so we stole through the unflinching fence as the sun on our right segued into a vadoek mud-toned … Yet again, to plus another opportunity inviting a flare up of colonial scars, Khathu pointed at gaping holes where the only explanation was that the graves were derelict, the ground long overdue in starting to cave in, and, he would add, for my benefit, even though the farmer tilled the land when he chose to uwuhloniphile lo umqwashu and the gathering of stones around it and so it was clear the farmer never went near the milkweed tree with his tractors … In another vivid moment as Khathu and I rifled through a roadside edge of the forest, small, unassuming stones suddenly appeared at our feet and my guide was quick to halt his walk and declaim

: Here, here are some of the other graves I told you about. You see

[pointing over the fence]

[me looking his way, standing to attention two footsteps away]

now this farmer won’t allow us to go through the fence but look closely, there they are

[Khathu pointing before him]

[me same posture]

you can see the arrangement of stones, of course the people who died here weren’t buried with fancy headstones so we’re not going to see that, but look

[still pointing while his face is turned to me]

[same posture me]

people are buried here

[face now turned towards the graves]

[walking ever so slowly towards where Khathu is pointing]

these stones mark their burial sites

12. I am assailed by voices ceding to informatics the task of quantifying the unquantifiable, fervid notations of all sorts of facts that torment me with their unstated realisation that the death register is already full of strangers’ names and not enough rigour will do justice to one’s grieving – to get into that subconscious region, as Marechera says, a region where a ghost has rights

13. What Lesego Rampolokeng calls graveyard upheavals of self-revelations do not come easily, what with processing death in an age of digital infinitude, our lives ever whirling in constant flux

: given our terms of reading the everyday, when we react to the moment in a clickety-clack of views, condemning the whole to a jumble sale, the Limbo of the Fathers narrowed down to one canonical gospel … Sihlala kwabafileyo only to help contextualize our foraging, writing reconstituted as a court appeal, a rural writer pleading on behalf of his own worldview

14. Syl Cheney-Coker’s impression that the graveyard also has teeth rests on an appreciation of the grave as the penultimate terrain on which Black rural lives are irrefutably manifest as dis/continuous in their fabrication, the cemetery as cardinal seat of amaXhosa cultural heritage – lineage, in this case, can be interpreted as drawing its power and validity from death, one’s clan praises as evidentiary of the villager’s embeddedness and oneness with place, neither placing on death a severe if fragile finality, thereby rendering the dead completely quiet in influencing events in the living world nor exerting undue reliance on the masquerades of memory

15. It is true that my epitaph in lieu of visits to my father’s grave owes its germination to the very thesis underpinning death in the rural imaginary: not only do we believe living continues even after death but it is in the dead that resistance to our subalternity is best crystallized

16. What Mqhayi waseNtabozuko means when he reminds us that We amaXhosa never die, for death to us is profit and gain,/ for there we get our strength,/ for there we gain our speed

17. To argue that graves, as emblematic of rural in/visibility in both Tyelera and elsewhere, authenticate the dead as crucial participants in the behavioral economies of the living is to repudiate that perception of the Mandelafrican village as nugatory, silent in matters of nation-building, counteracting the primacy of the settler’s framework of worthiness, that prevailing fantasy of an unpeopled countryside available for capture and definition, accentuating those human figures who appear to blend into the natural environment so that even when we see these villagers afforded some visibility, we don’t really see them as they are invisibilized by their surroundings, their dispossession justified by the very location that defines their being

: a world of bizarre customs as ogling prospects, beholden to NHC protectionism if not exotification

: of Contralesa paternalism dressed as indispensable benevolence

: of broken English, a world that has to apologize for its poverty, a world that gets by thanks to the outsider’s affirmation and rescue, appealing on its knees in Sassa offices

: of long queues outside the clinic, of bad roads, of overcrowded classrooms, of skinny goats, of barren farming fields, of absent fathers, of grandmothers left to raise their daughters’ children alone

: a world that has accepted its place in the isolation cell, ever folding its hands on laps outside the helper’s office, eagerly anticipating a bank notification

: a world that has learnt the meaning of silence, embracing its muteness with the bum jiggle and spit on its calloused palms come the MEC’s visit

: a world no one wants to belong to

: a world of shame

: a deadened world

: a world, ultimately, that is absent

18. To pay a visit to one’s family graves, then, is to summon into presence the physically absent in a way that reasserts the validity of one’s ways of knowing – what T. Spreelin Macdonald, in considering Vonani Bila’s Jeanette, My Sister (about the death of Bila’s youngest sibling, who is buried between two houses at Bila’s Shirley Village of Limpopo, her grave marked with two flat stones), calls A LABOR TO RESURRECT AND INTERACT WITH THE DEAD, thereby seeking to affirm a persisting bond between [Bila and his sister] that resists [Jeanette’s] sinking into absence

19. I quote from the City Press series Faces of Marikana, about a miner born in the village of Paballong, near Matatiele

: Thabiso may have known that he was going to die …

In his modest shack in Nkaneng a few months before he was killed

, he told his wife

, Mma Kopano

, the mother of his only child

, whom he lovingly always called Dear

: Respect me when I’m dead

: Respect my grave

A pre-ending and an alternative lie, who is Joy and who is Joyce?

: The dead won’t sink

They keep returning to the surface of the dam, some as skeletons, some bodies half-decomposed, floating aimlessly or otherwise circling the dam in search of familiar faces, still in their tattered burial blankets of ox-hide; whole families dead during a famine or the last tribal war in memory – after the year’s harvest, the villagers in the dam come alive and talk with the living, asking them for updates of the year they missed out on, parents admonishing children for missing the last festival a year ago, patriarchs leaving orders for what is to be done with their livestock and land in their absence, miner-husbands conferring with housewives, great uncles answering to suitors who had come, in their absence, to ask after the hand of an orphaned granddaughter in marriage, fathers laying charges with the chief’s emissary for wives they suspect to have committed adultery without their expressed consent, fathers discussing the next suitor for their wives, matriarchs informing their sons of women they wish to be their next wives (friends’ daughters, women from other villages … domestic worker-women they consider to be lifelong younger sisters), young boys forlornly watching their former love interests carrying babies they did not father, men who died as boys waking up to confront younger brothers who now have as much hair on the sides of their faces as … fathers who “left” under mysterious circumstances and might still be suspicious of their wives’ skills in the cooking compound and finally the chief, when he elects to speak, rising from his throne to lament that the affairs of the land are going in the direction of the unknowable … a dot of wet mud is made by dipping a finger in the shallow waters and pressing it on the centre of your forehead, as sacrifice withal

In this dream, I am the only one tasked with going around the dam and striking up random conversations with those who have no relatives around or beef with anyone present

20. A version of the present free of the anxiety to belong to any absolutist trope, given an incongruous understanding of time and space as they operate within a rural setting in discoursing around the settler notion of African hegemony, as defined by not just a recreation of past models by way of manufacturing somewhat idealistic future modes of being, this onrush of tired whimsicality still caught up with the need for Western science to correspond to our rationality-defying present

, hence we look back there

really look

to finally see how, in navigating the forest of stereotypes that weigh down the rural, the absenting of our ancient ways in reading the world

, IT IS THE DEAD WHO BEAR WITNESS TO OUR LIVING

, less the living eyewitness thereof

: as if the names, the gestures, the places, and the time, having bloomed separately in simple maxims, were for an instant to accept being united under a common law so that one would know finally, as in the hard light of a blunt interrogation, who made what, where, and when (Jean Frémon)

When I was finally taken by Khathu, late in that June 14, 2017 afternoon, to the home of Ntayise Dyakala, a member of the Salem Community Property Association, the body that had been fighting to reclaim 66 square kilometers of land on behalf of the Black residents of Tyelera since 1998, early supper was served with a spoonful of sepia memories of those who’d experienced firsthand the Fourth Frontier War that robbed Tyelera’s Black community of a portion of Tyelera they had occupied pre-1812 and which now belonged exclusively to settler descendants, among them the white owners of Kikuyu Lodge and the commercial farms tracing their title deeds after the wars of dispossession, those owning the forests and roadsides where much of Khathu and my decolonial flesh fictions on rural persecution occurred … the next morning, as Ntayise Dyakala and I entered his ancestral graves at the Bradfields Farm, besieged by a selfish need to construct a more concrete and less ah ngimnandi testimony verifying MY EXPERIENCES of death within a rural space, Ntayise Dyakala furnishing me with one explanation after another about these or those family graves, a gospel of plangent cracks, to witness Black anger materialize at the crunch of a footstep on gravel, polluted as we are with grief (Wopko Jensma), forever feuding against the rural’s marginalization

; to palliate the spirits of our upbringing, percolating with vehement repudiation at conventional ways of mourning, of remembering, of seeing, to have the revelation penetrate your bones, milking the marrow

: WHEN IT COMES TO RURAL LAND REFORM THE REAL MEAT IS OVERWHELMED BY TOO MANY FLAVOURS

I remember telling myself with a clarity borne of having seen too many burial sites and heard enough oral testimony the previous day

: Kakade there was a community of Black people living on the Salem Commonage phambi kokuba iTyalera became Salem

20. Song, here in the form of a prayer, says Marian De Saxe, of Vuyisile Mini et al approaching death as if enthusiastically, is transformed into A SHOW OF STRENGTH AND PROTEST AND HOPE, in much the same way that Nkosi Sikelel‘ iAfrika evolved from a prayer to a liberation song to an anthem … SINGING ONE‘S WAY TO THE GRAVE is also A DEFIANT ACT of altruism WAITING FOR AN AUDIENCE TO ACT, as ASSERTION OF EXISTENCE AND BEING

Among his old family graves, Ntayise Dyakala says to me

: They were all buried here before we were forced away. You see

[pointing over to the most recent grave]

[me looking his way, listening]

you can tell from that name we’re not the only ones

[the Dyakalas]

who have family buried here

I wanted to understand what this assertion of the unbreakable connection of identities between the dead and the living … not LEAVING … meant regarding how the villager processes death so far as it concerns the ways in which we collectively shape current rural identity, memory included … to commune, so to speak, with the graveyard of relationships that inform my philosophies … I have been considering the place a grave occupies in the rural worldview long enough to know that the grave has, overtime, shifted its position from the venerated to the diversionary, from when one feared pointing at the graveyard (or did so with a crooked index finger so as not to “provoke” the wrath of those “asleep” in the cemetery) to a familiarity such that communal grave-digging sessions back in my village can turn rowdy without fear of ancestral retribution ever figuring into the transgression … It is never clear, in weighing the cost of my silence on how dying remains a unifying force in rural communities, if presiding over Grave Crimes Against [my] Struggle is to set myself up on the dock, giving evidence against my other selves on the witness stand, prosecuting on behalf of my ideals: disputatious thinking, sure, offensive to the senses, but nonetheless a grave narrative of mis/counting the funerals I’ve been to and those I’ve missed and those I don’t remember attending; to get close enough to the edge of the abyss and consent to what memories, quotes, scents I carry to suggest a redefinition of the borderscape

Caught in the maze of unbearable absence (Joseph Guglielmi), in remembering those I love and am linked to by blood, talking Black rural death is a means of expression at grief’s disposal, what Maurice Blanchot would call the gentle madness of remembering forgetfully … rural death in this case cannot be measured as pure and simple loss … it has to mean more

: Where is the least power? In speech, or in writing? When I live, or when I die? Or again, when dying doesn’t let me die?

22. The accused is not my father (Ah Chul’unyathela, Malamb’edlile!), retired as he is to his absenteeism … but a son who has seen with the eternal corner of the eye too many things I instantaneously consigned to the back of my mind, still working the treadmill towards the finitude of my understanding, taking that short walk to the grave, only a rational thought away … Only a strong feeling away … Meeting all the versions of yourself which did not come out of the womb with you … Those who wear their skeletons on the outside

23. Sithetha nge mvuma ‘kufa, nge insurrectional avowals, nge tjotjo estrongo for only uVerwoed

: Love is found even where the dead lie

24. Using death in the service of a search for empowering beliefs about the rural, rejecting the imprisoning notion of the villager as meek effigy, excavating scraps of Black rural voices babbling polyglot-al to polemical effect, taking up the associative inquiry of our grazing living

, not those voices who confront without necessarily dislodging even in praise of the threat of forgetting, aware that the infiniteness of the threat has in some way broken every limit

: The fly that has no one to advise it follows the corpse into the grave

The Tyelera moment teaches me to neither fear the final day nor wish for it – death is the temporal villager in the city, wandering in a warren of exile-forced solidarity with the world and the multitudes of identities that intersect at his heart, a raucous, if consistently improvisational, montage of maestro boasts regardless of the limits of his migrant-mobility, using an assertive language to solidify fragile networks of thought-currency, twisting lines of not forgetting into twines of punishment and that awareness

: IT IS NOT POSSIBLE TO QUIT THE ANCIENT IDENTITIES

Question me on how we read the present

, suggest to me the need for a rural-bound and unabashedly intrusive manipulation of memory

, to clean up the canon of limited and limiting beliefs about the rural

, to entice redemptive reports around village living

and not this perceived neutrality that comes with merely curating the act of rural typecasting at the expense of pushing against our consignment to the bottom of the page/afterthought paragraph/back of the museum

: There can be this point, at least, to writing

, says Blanchot

: TO WEAR OUT ERRORS

Ever the trier of the Quenellian fact of constraint, the second day, leaving by way of Makhanda, on the road, early noon, Ntayise Dyakala with his son, I REMEMBER: abantu abadala bagqiba = sivile = siyavuma = UMNTWANA UDE WABA NGCONO … a raindrop of a motive sneaks up on me with the politeness of an anus pump, to retrain the bowels as I am third-worlding on the R343

: History, the stockpiling of daily events, works in the moment and the moment belongs to the present; those who mourn must learn to appreciate the dead before they can appreciate the living … we’re not made to talk or write for eternity, but for the moment, and it’s the accumulation of moments that makes continuity: Edmond Jabès

– everything has changed except the graves: Mzi Mahola

– not dead but sleeping: Anna Della Subin

– the dead ones who are not dead, the sleeping ones who are not sleeping: Nichols

– endlessly signifying what is absent: Frémon

– the point of this discussion is that she did not die: Georgia Anne Muldrow

– you’re dead, Kintu rebuked … what have you come back for: Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

25. The past to which we were subjected, which has not yet emerged as history for us, is, however, obsessively present (Edouard Glissant)

26. Says Mzwandile Matiwane, in To My Sisters? Once I am dead/ urinate on your hands/ and wash your faces/ and cleanse off the curse/ that has befallen the AmaNqarhwane clan

Says Mandla Ndlezi, in When It Comes? O, dig it/ like a cave/ and let me squat/ inside and wait. // Snugged in/ animal skin/ ready to/ get up and go!

27. Satisfied, I came among my guests like a man who has returned from the grave to complain about the death certificate … In Black Sunlight, Marechera

28. It is in Alfred Qabula, being of Flagstaff, rural Transkei, that we see someone wholly underplay the factsheet of his grieving, making it clear that to count the bodies of the dead has already exhausted its effectiveness, that addressing the elusive monster, mano a Cde, can be another approach in foregrounding the heart’s clangs of pain

: Death

enemy of man

Woe unto you …

then

29. There is no use arguing the case of our social death if to be alive means even our births are already suspect

30. On the threshold of a rejected birth

, says Jabès,

we write in the shadow of what has been written, but never read

In his dissenting judgement when the Tyelera land claim came to the Supreme Court of Appeals in Bloemfontein in February 2016 (the commercial farmers and lodge owners of Salem appealing the Land Claims Commission’s original ruling in favour of the Tyelera claim; majority judges in the SCA assenting to Tyelera’s claim), Azhar Cachalia, Judge of Appeal, weighs the evidence of two witnesses for the Tyelera community in the following manner

: In response to a further question as to how Salem got its name, he answered almost as a child telling a story would … His evidence was difficult to follow, perhaps due to his lack of education and literacy … the sequence of events itself is bizzare … Nondzube’s hearsay evidence was relied upon to … He is uneducated and his evidence was not easy to follow …

I quote Cachalia in one lump of mangled quotations especially to show how the infantilizing of Msele Nondzube and Cachalia’s insistent valuing of formal education in discrediting Ndoyityile Ngqiyaza’s testimony points to a larger problem in how Mandelafrican rural people suffer most rampantly under essentialised notions of identity, even to highlight the parts that verify how the methods of rural memorizing can never be authenticated in Romanesque scrolls but that which is lent and borrowed through story, gesture, personal moment, dream, ritual and myth, the past kept contemporaneous one generation after another even as memories fray

31. Says Motlalepula of Boroeng village and brother to Khanare Monesa, slain during the Marikana Massacre, Khanare’s wife already with child at the time of Khanare’s passing

: My only hope is that when his child is born, he’ll look exactly like him

: The child will be a reminder to all of us that we once had a beautiful brother who was killed

Research for this essay was supported by a grant from the Taco Kuiper Investigative Journalism Fund, run by Wits Journalism (Wits University).

All pictures feature Funisile Khathu and were taken by the writer while visiting some of the graves belonging to Tyelera’s African population.

Reading List

Where White is the colour/Where Black is the number, Wopko Jensma, The faces of Marikana, City Press, Born in Africa but..: Women’s poetry of post-Apartheid South Africa in English, Isabelle Vogt, Nomvula, Freshlyground, Black Insider, Dambudzo Marechera, My Spirit Is Not Banned, Frances Baard as told to Barbie Schreiner, No mining in Xolobeni, demand activists, GroundUp, Collected Poems, Alfred Temba Qabula, South African History Online, These Hands, Makhosazana Xaba, Eulogy, Grace Nichols, Salem Party Club and Others v Salem Community and Others (2017, January), Salem Party Club and Others v Salem Community and Others (2017, December), Not dead but sleeping, Anna Della Subin, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays, Edouard Glissant, Johann Louw paints as counter-feminist and settler fantasist of sorts, Percy Mabandu, Ah, but your land is beautiful, Zamansele Nsele, Habari Gani Africa Ranting, Lesego Rampolokeng, Steve Biko and Black Consciousness in Post-Apartheid South African Poetry, T. Spreelin Macdonald, The Graveyard Also Has Teeth: With Concerto for an Exile: Poems, Syl Cheney-Coker, Umfi uMfundisi Isaac William Wauchope, SEK Mqhayi, Sing Me a Song of History: South African Poets and Singers in Exile, Marian De Saxe, When It Comes, Mandla Ndlezi, Kintu, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, To My Sisters, Mzwandile Matiwane, Writing At Risk: Interviews Uncommon Writers, Carlos Fuentes, The Dead Protect Us!, Daily Sun, Endlessly signifying what is absent, Jean Frémon, The writing of the disaster, Maurice Blanchot, An Uneducated Discourse, Xola Stemele, The book of remembrances remains to be written, Joseph Guglielmi, Arrow of God, Chinua Achebe, Itineraries of a Hummingbird: an interview, Edmond Jabès, Everything has changed (except the graves), Mzi Mahola, A Thoughtiverse Unmarred: Prologue, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Memory of a dead memory, Edmond Jabès, Hybridity and Transformation: The Art of Lin Onus, Bill Ashcroft