Published by Chimurenga, the Chronic is quarterly pan African newspaper that gives voice to all aspects of life on the continent and celebrates our capacity to continually produce something bold, beautiful and full of humour.

Produced in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Nairobi, Paris, Lagos, Yaoundé, Accra, Kinshasa, Dakar, Kampala and Delhi, and distributed globally, it seeks to write Africa in the present and into the world at large, as the place in which we live, love and work.

The new issue, available now, features reportage, creative non-fiction, autobiography, satire, analysis, photography and illustration to offer a richly textured engagement with everyday life.

In its pages artists and writers from around the world take on the philanthropic complex to unravel the philosophies of dependency and power at play in the civil society of African states. Paula Akugizibwe assumes observer status at the African Union to uncover the charm offensive that keeps the West in control, while Parselelo Kantai exposes the manufacture of post-election peace in Kenya. Also, we journey into the AU headquarters in the heat of the political crisis in Mali and speak with Raila Odinga about the arithmetic skills of Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission.

Elsewhere Yves Mintoogue and Adewale Maja-Pearce diagnose the First Lady Syndrome in the political patronage of Chantou Biya and Dame Jonathan; Agri Ismaïl eavesdrops in on Islamic finance after the market crash; Deji Toye looks at the Nigerian art of patronage; and Cédric Vincent exposes the political rhetoric that caused all the chaos at both Benin biennales of 2012.

As an alternative, three pan-African art projects overcome maps and institutional bureaucracy through networks and synergies; Ghana’s controversial duo FOKN Bois fuck with the puritanical mores in the world’s most religious country; and we listen in on the rebirth of the new thing in Cape Town’s jazz scene.

The Chronic also goes back to university to recount seventeen stories of love and learning under the World Bank and interviews Fred Moten and Stefano Harney on the possibility of staging a revolution “with and for” the university.

The wide-ranging sports coverage kicks off with Bongani Kona’s reflection on Zimbabwean players in South African rugby. In addition, Simon Kuper points out Africa’s best footballers aren’t African and Akin Adesokan learns 24 tricks of the forehand from Roger Federer.

The stand-alone Chronic Books magazine is a self help guide on reading and writing. Learn how to be a Nigerian from Peter Enahoro, Nigeria’s ‘woman of letters’ and the masters of Onitsha Market Literature. Get advice on how to live and how to write from Mohsin Hamid and Werewere Liking; meet the next generation of playwrights; and find out why you should be reading Ken Saro-Wiwa, Jose Saramago, Eric Miyeni, Andile Mngxitama, Gonçalo Tavares, Vivek Narayanan, Nthikeng Mohele, A. Igoni Barrett, Abdellatif Laâbi, Gabriela Jauregui and many more.

Get the print addition of the Chronic from select retailers throughout South Africa (including Exclusive Books, selected Spaza, independent bookstops and on the street in the first week of release), as well as in select shops in Abuja, Lagos, Nairobi, New York, London, Berlin and The Netherlands (get a for a full list of stockists worldwide here).

The Chronic is also available as both a print and digital edition in the online shop.

The Chimurenga Chronic is funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation and the Goethe-Intitut.

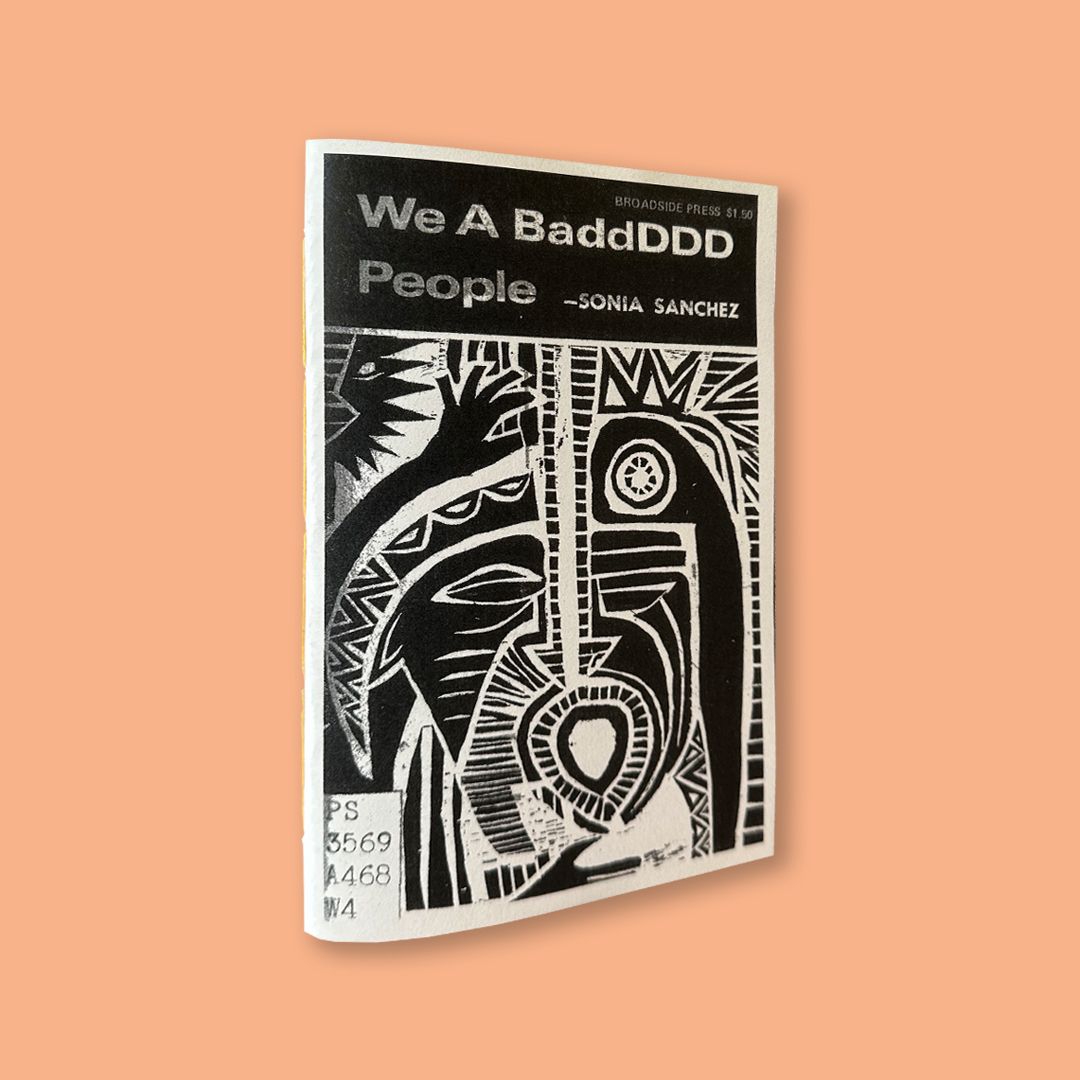

We A BaddDDD People by Sonia Sanchez (Broadside Press, 1970)

We A BaddDDD People by Sonia Sanchez (Broadside Press, 1970)

Sonia Sanchez's second book of poems (Broadside Press, 1970), similar to Homecoming (1969) in experimental form and revolutionary spirit, is dedicated to “blk/wooomen: the only queens of this universe” and exemplifies the poetics of the Black Arts movement and the principles of the black aesthetic. It depicts the experiences of common black folk in courtrooms, slum bars, and on the streets, with pimps and jivers, boogalooing and loving Malcolm X. It celebrates the majestic beauty of blackness and speaks of revolution in the language of the urban black vernacular. Rhythms deriving from the jazz and blues of John Coltrane and Billie Holiday create a poetry of performance in which the audience participates vigorously in meaning-making. Experimental in style, it is antilyrical free verse, using spacing, slash marks, and typography as guides to performance.

Characterizing Sanchez as a genuine revolutionary whose “blackness” is not for sale, Dudley Randall's introduction leads into the first of three sections, “Survival Poems,” which approach survival from political and personal perspectives. Some show how “wite” practices imperil black people's survival, seducing by heroin, marijuana, and wine or by exploding dreams. Others show how blacks undermine their own survival: the “makeshift manhood” underlying sexual neediness in “for/my/father,” the willful blindness of black “puritans,” and the hypocrisy of pseudorevolutionaries whose rhetoric masks self-indulgence. Personal poems recording moments of near-hysteria, depression, and longing lead to the revolutionary vision of “indianapolis/summer,” proposing communal love as a necessary prelude to real change.