The Chronic is a one-time only edition of Chimurenga which takes the form of a speculative newspaper. Back-dated to the 18-24 May 2008 – the first week of the xenophobic violence across South Africa three years ago, the Chimurenga Chronicle is an opportunity to provide the depth of reporting and analysis that should have appeared during this period. The newspaper also looks outward – covering events, scenes and situations from around the world during this period. And it launched today!

It was Sun Ra who said it a long time ago: “Equation wise, the first thing to do is consider internal linktime as officially ended… we’ll work on the other side of time… we’ll bring them here through either isotope, internal linkteleportation, transmolecularzation… ” . The time was 1974 and Space was The Place. A prolific jazz composer, bandleader, philosopher, afronaut and historian, Ra was ahead of his time.

Almost four decades later, it is increasing clear that time, once thought continuous, is actually marked by radical disjunctions and overlapping time-spaces. What’s more, the tools we have at our disposal, particularly in the area of knowledge production, do not help us much to grasp that which is emerging.

What we need now is a Time Machine! A device that will allow us to work “on the other side of time”, to discover possibilities for new ways thinking through the “having been and yet to come.”

The Chimurenga Chronicle such a machine, a once-off edition of a speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present. Both a bold art project and a hugely ambitious publishing venture, the Chimurenga Chronicle comprises of a 96-page multi-section broadsheet, the stand-alone 56 page Chronic Life Magazine and a self-contained 96 page Chronic Book Review Magazine.

By imagining the newspaper as a low-tech time travel machine, our aim is not only to reanimate history, to ask what could have been done – but also to provide a space from which to re-engage the present and re-dream the future.

The print edition includes a 128-page multi-section broadsheet, packaged with 40 page Chronic Life Magazine and the 96 page Chronic Book Review Magazine.

An intervention into the newspaper as a vehicle of knowledge production and dissemination, it seeks to provide an alternative to mainstream representations of history, on the one hand filling the gap in the historical coverage of this event, whilst at the same time reopening it. The objective is not to revisit the past to bring about closure, but rather to provoke and challenge our perception

Featuring contributions from Mike Abrahams, Olumide Abimbola, Toyin Akinosho, Paula Akugizibwe, Sello Alcock, Max Annas, Gabriela Carrilho Aragao, Ayi Kwei Armah, Sophia Azeb, Robert Berold, Marlon Bishop, Louis Chude-Sokei, Jean Comaroff, John L. Comaroff, Imraan Coovadia, Goran Dahlberg, Kwame Dawes, Jacob Dlamini, Manu Herbstein, Sean Jacobs, Neelika Jayawardene, Billy Kahora, Parsalelo Kantai, Bill Kouèlany, Jackie Lebo, Miles Marshall Lewis, Percy Mabandu, Munyaradzi Makoni, Dominique Malaquais, Lionel Manga and many more

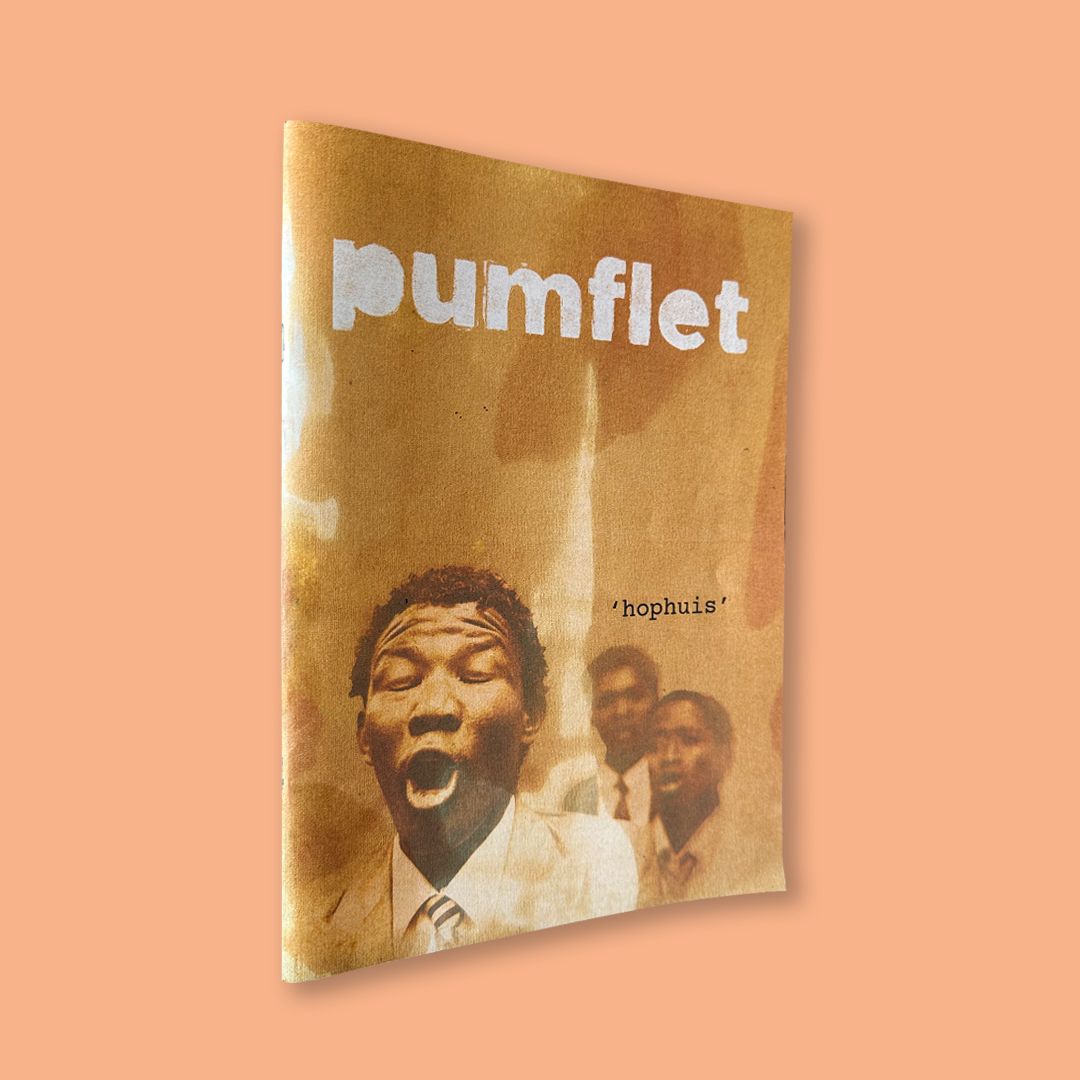

Pumflet 'Hophuis' (Wolff Architects, 2023)

Pumflet 'Hophuis' (Wolff Architects, 2023)

'hophuis' documents a series of journeys to and activations made at the Steinkopf Community Centre in Namaqualand in South Africa's Northern Cape. The building was at once a lively centre for communal and political gathering, (albeit controlled by the church) but stands today as an open, civic-scaled volume of broken walls, a concrete floor, and with its electrical and water services completely removed .

The town of Steinkopf itself is situated in what was declared a 'coloured reserve' by the apartheid government in 1948, and the place is significant for a number of reasons. Its original name 'Kookfontein' (which referred to an ancient water well) was lost when it was renamed by German missionaries who settled there in the 18th century.

Along with a new name, the missionaries bought with them what James Baldwin has referred to as 'theological terror': warnings of eternal damnation for all who followed the local Nama, Khoi and other indigenous spiritual practices. Dance and song, a core part of the spiritual practices of the Nama in particular, were prohibited. Thus, many of these cultural practices, along with the Nama language, remain treasured by a few cultural custodians but are otherwise mostly forgotten.