Ranga Mberi travels back in musical time to the 1980s and 1990s, the era of sungura music. Dubbed the “authentic sound of Zimbabwe”, sungura weaved together Congolese rumba with Zimbabwean jiti and Tanzanian kanindo. Rooted deeply in the struggles, heartbreak and suffering of the times, but also in joy and celebration of common people – those who danced to it “for no reason” at growth points, rural shopping centres and township parties – the music captured the essence of life and the national mood in Zimbabwe during the best and worst times in its history.

As always, there is the question of beginnings. Do I begin with the stone-washed jeans and bright viscose shirts? Or reel back to an earlier time, of bell-bottoms and afros? Or should I begin where sungura music began? But there isn’t a single story about how this sound, borrowed from far off countries, came to be regarded as the authentic sound of Zimbabwe.

Let’s start with the story of Mura Nyakura.

It is the 1940s and 1950s, and Nyakura is working for a trader, a job that allows him to travel between what is still Rhodesia, and Central and East Africa. He falls in love with Congolese rumba music, and he brings home many records. Not just records, but sound. He brings home a sound.

At the time, the locals back home are obsessed with hair-gelled black American jazz. The hot acts are performing in groups, mostly quartets. They burn stages in their dark suits, shiny hair and Stetson shoes. They have exotic names like De Black Evening Follies, The City Quads, the Epworth Theatrical Strutters and Capital City Dixies. They all worship Nat King Cole.

So, rumba is merely a niche fascination. But years later, a few daring bands emerge, with the influence of exiled Congolese bands such as the Great Sounds and OK Success, and they start experimenting with this new African sound, hoping to break away from Western influences. They weave together rumba and traditional jit sounds, laying the foundation of what in future will be sungura music.

Another story.

It is the 1960s, and fighters from across Southern Africa are stationed in camps across the Tanzanian countryside, training to liberate their people. They pass the empty hours listening to kanindo music, a close cousin of the rumba. The music is named after Phares Oluoch Kanindo, a politician and music producer, whose studio is churning out hits from his POK Music Stores. The refugees discover and fall in love with East African benga music, led by doyens such as John Ogara and David Owino.

It is the 1960s, and fighters from across Southern Africa are stationed in camps across the Tanzanian countryside, training to liberate their people. They pass the empty hours listening to kanindo music, a close cousin of the rumba. The music is named after Phares Oluoch Kanindo, a politician and music producer, whose studio is churning out hits from his POK Music Stores. The refugees discover and fall in love with East African benga music, led by doyens such as John Ogara and David Owino.

Among those young fighters in the camps are the likes of Ketai Muchawaya, and other comrades who are still known by their war names – Dhembo Kenyatta, Rex Moto Moto, Stalin Organ. They immerse themselves in the music, and form a makeshift band to entertain fighters and refugees in the vast camps. As the war draws to an end, they return home and, together with Marko Sibanda and Knowledge Kunenyati, form Kasongo Band, named after the popular Orchestra Super Mazembe song ‘Kasongo’.

Their first hit is ‘Asante Sana’, a Swahili song to thank the Nyereres and Machels for providing refuge and support to Zimbabwean fighters. Their sound is still kanindo, but their new fans have come to know it as sungura. This is because the records many had brought home from East Africa were released by AIT Records, which had one label named Sungura – rabbit or hare in Swahili.

These are some of the stories of how sungura was made. But as stories are wont to do, like tributaries, they flow into each other. Now that we had sungura music, we naturally had to have a band called Sungura Boys. More than forerunners Kasongo Band, Sungura Boys were to have the strongest influence on the genre. Not only did they adapt the sound, but would give us many of the genre’s superstars.

The comrades had brought home the sound from East Africa. Someone had to make it local, and this happened in Dzivarasekwa, a large township in the west of Harare.

To tell this story, I have to press fast forward to a Friday night in 2016, at a beer-soaked joint called Queen Elizabeth Hotel in a seedy corner of downtown Harare. Sungura music is dead, and we are on rickety bar stools, asking a middle-aged man why. His name is Shepherd Chinyani. He should be a legend, with a statue in his honour somewhere in Zimbabwe, his name in all the books on Zimbabwean music history that we have never written. He is a bitter man with a sharp tongue, with very little good to say about any of the young sungura artists scheduled to perform later that night. I can understand this anger.

Chinyani was one of the pioneering members of the Sungura Boys, a nursery for at least a dozen of some of sungura’s leading lights. In the early 1980s, Chinyani’s small home in Dzivarasekwa was a mecca for wannabe guitarists coming from all over the country. Not only did they come to learn how to play, many of them stayed rent-free in his home and ate his food. They went on to find fame. He did not, and struggles to pay rent.

Sungura’s sound as we know it now, is descended from Chinyani and Ephraim Joe, the two patriarchs of the Sungura Boys. They took the kanindo sound and gave it an extra edge; the lead guitar remained the key instrument, but pitched just a bit higher, Chinyani explained. The pace got faster, capturing the buoyant mood of the time. Often, chimurenga music is seen as the “authentic Zimbabwean sound”, because its guitar sound was plucked from that most Zimbabwean of instruments, the mbira. On the other hand, sungura was more an adaption of foreign sounds, from Congolese rhumba to East African guitar sounds. But while Thomas ‘Mukanya’ Mapfumo’s chimurenga focused on political struggle, sungura was more diverse. While they were political, sungura artists shunned Mukanya’s direct style, instead opting to deploy idioms and subtlety as ways to speak to power. Yet sungura rooted itself among the masses, from the rural ‘growth points’ to urban townships, because many could identify with its messages – the daily social struggles of the people and the many complexities of human relationships.

One of the Sungura Boys’ earliest hits, ‘Kutsvaga Basa’, is the lament of a young rural boy struggling to find work in the big city, staying at the home of a no-nonsense uncle. Many could relate. The song introduced the vocal abilities of the Chimbetu brothers, Simon and Naison, whose harmonies later were to set them apart when they went off to find their own success as the Marxist Brothers.

It was not just the Chimbetu boys who launched themselves from this band. Chinyani reeled off the names, a roll call of legends: Ephraim Joe, John Chibadura, Alick Macheso, Nicholas Zakaria, System Tazvida, Mitchell Jambo, Solo Makore, Tineyi Chikupo, and, the best of them all, Leonard Dembo.

There are stories about each of these men, and how they made their break. John Chibadura was fresh off the farm when he arrived in Dzivarasekwa, “He knew nobody, knew nothing about the city.” Alick Macheso, the genre’s most commercially successful artist, was discovered by chance while playing a box guitar under an avocado tree at a house on Chinyani’s street. He was recruited as a stand-in rhythm guitarist, until one day the bass man didn’t show up. He took the gap and, years later, totally redefined the bass guitar’s role in the genre.

“All these were rural boys,” Chinyani told me that night. It was meant as an insult, but isn’t that the charm of it all? Sungura in the early 1980s was a reflection of the time – young rural boys flooding into the cities to get a slice of this “new dawn” thing. They often lived in squalor, just as they did at Chinyani’s. You can tell in their music how much the simpler rural life they had left behind was missed. There are songs in which parents write long letters to their sons in the city, begging them to come home. They sing about parents advising their children not to lose themselves in the city’s bright lights. There are songs in which singers long for the rural women they left behind, not the fast city women.

John Chibadura, for instance, has a string of songs with women’s names as titles: ‘Onai’, a song about a woman who broke up with him even after he bought her a nice dress. There’s the song about ‘Everjoy’, who found a richer guy. There’s ‘Jude’ and ‘Jenny’, and others.

It’s hard to find a 1980s sungura music song that isn’t about some trouble or suffering of some sort. There were songs about poverty, heartbreak, witchcraft, drought and tragedy. The irony is how all these grim songs shook parties in townships in the towns, and were all the rage at growth points, and dusty rural shopping centres where it was not uncommon to find dozens of people dancing away for no reason.

It was only in the 2000s that we saw the end of “tear washed Sungura”, as Charles Tembo, of the Midlands State University’s Department of African Languages and Culture, called it in a paper on Tongai Moyo, one of the genre’s modern proponents. Tongai Moyo “breaks the tradition of tear-washed music… contrastingly, while the music of Sungura musicians such as John Chibadura is largely marked by pessimistic existentialism, the music of Tongai Moyo demonstrates transcendental attitudes towards life,” writes Tembo in An Embodied Culture of Optimism and Struggle: The Sungura Music of Tongai Moyo.

I now remember thinking, as he spewed vitriol at modern sungura and glorified its old icons, just how closely Chinyani’s fate reflected the state of the music that he helped create. The genre’s best years are behind it; only nostalgia remains.

This was the music that once best captured the national mood at key turns in Zimbabwe’s history, from the euphoric early years to the economic and political struggles of latter years.

In newly independent Zimbabwe, it was the sungura rhythms that captured the joy and euphoria of the time. There is “Makorokoto” (“congratulations”), a fast-paced celebratory tune by the Four Brothers, which celebrates the end of years of suffering, and the onset of peace. From Alex Chipaika’s opening rhythm guitar riffs, the pace is relentless, even rising mid-track. Eddie Zulu on lead guitar and Never Mutare on bass form a lethal combo that brings out the celebratory mood of the track.

Sungura is predominantly sung in Shona, but it is also hugely popular among the Kalanga people of south-western Zimbabwe. The two fathers of Kalanga sungura were Nduna Malaba, known as “Ndux Malax”, and Solomon Skuza, whose 1980s song, “Banolila”, remains an anthem. Like Kasongo Band’s Ketayi Muchawaywa, Skuza developed his music while in a guerrilla training camp during the 1970s. His band was called Fallen Heroes, in honour of liberation war fighters.

Musically, the Kalanga brand of sungura has a faster pace to it than other sungura, and is often laced with humourous skits and chants mid-song. Even amid the humour, weighty issues were subtly tackled. Khumbulani Moyo and his Tukuye Super Sounds mock one Chakanetsa, a notorious Shona cop operating in the predominantly Ndebele area of Tsholotsho. The success of these acts showed an ethnic diversity in sungura that other Zimbabwean genres, such as Chimurenga, lack.

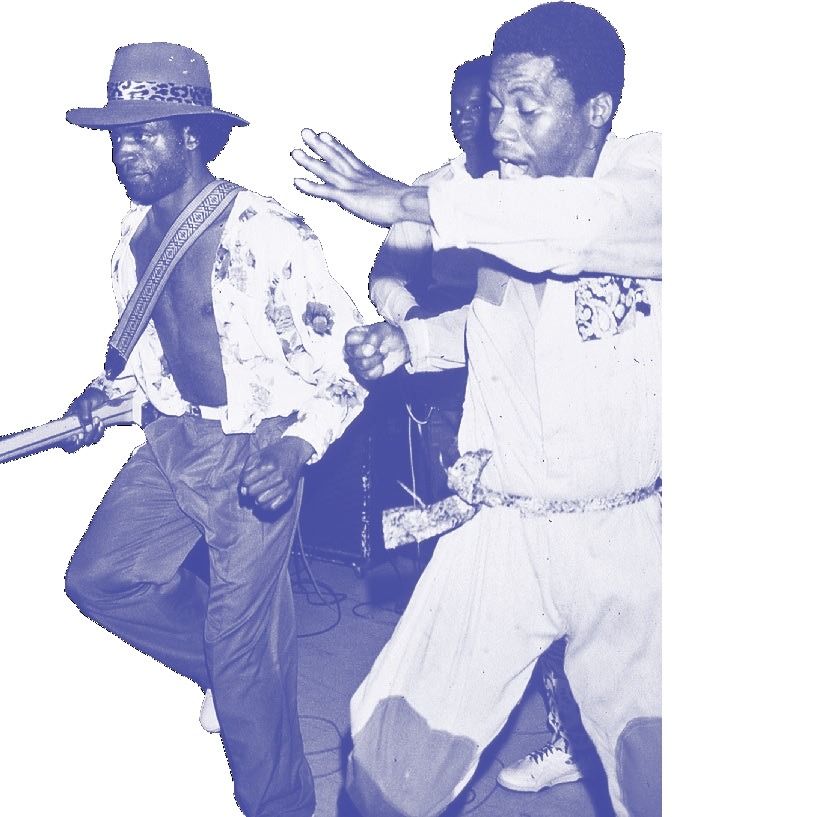

The stories of sungura’s golden years are also told in the romantic album covers. The covers portray young men who, much like their nation, were full of confidence that they were on the way up. Devera Ngwena Jazz Band had the best ones. The liberal outfits – bell-bottom trousers, large shades, floral shirts and afros – struck a chord in this new, young nation that was only beginning to explore its freedom.

Devera Ngwena had come out of the booming mines of Zimbabwe’s heartland, but their fortunes fell with the collapse of the asbestos industry that had funded them. The mine tied them down for years to a slave contract. The mine would fund the band, as long as the men surrendered the bulk of their earnings. When the band became popular, the mine raked in the money at their expense.

In the 1990s, Zimbabwe began to go through great changes, and so did sungura. A government that had flirted with socialist pretences swung right, and adopted the neo-liberal Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) of the International Monetary Fund. The policies threw thousands of people out of work, and prices rose. Into all this entered Leonard Zhakata, with his colourful viscose and silk shirts, and baggy trousers often accessorised with more than one belt. His sungura borrowed heavily from soukouss, a fast-paced brand of rumba, popularised by the likes of Kanda Bongo Man, a nod perhaps to old shared roots.

But beneath all that glitter was a genius, whose lyrics in his 1994 hit, ‘Mugove’, captured the abuse of power by those in authority, and the growing divide between the haves and the have-nots. Over the next decade, his socially conscious music would be banned from national radio.

The tough ESAP years gave us some of the best sungura, a testament to the genre’s role at the time as an outlet for the poor, from the countryside to the urban townships. In 1991, Leonard Dembo was recording his seventh album when the government started slashing subsidies and raising taxes. Suddenly, he discovered that not only had the takings from his last album been eroded by the record company taking more than its share, he also now had to pay more taxes. So he wrote ‘Chinyemu’, a song about how the poor worker always toils the most, but always takes home the least.

Having been too young to have seen the 1990s sungura singers play, I have always believed that the closest I could ever get was to visit the places where they used to play. Much like the decline of the music itself, each old venue I have found is more depressing than the last. Leonard Dembo had hundreds of hits and over a dozen albums, but he only ever shot two music videos. There is only one known video of him performing live. It was shot sometime in the early 1990s, at a township beer garden called Rusununguko, in Chitungwiza near Harare. Back in 2008, while covering elections for a newspaper, I found myself at Rusununguko. The name means “freedom” in Shona, but I discovered that it was being used as a base for a local ZANU–PF youth militia. No music was played there anymore.

I once also walked into the Rose & Crown, a run-down roadside motel in the middle-income suburb of Hatfield, Harare. I had been told that this was the joint where Dembo and his band, the Barura Express, used to rehearse for hours into the night, sometimes well into the early hours of the next day. The paint had peeled off the walls, the stage was broken and the rusty sound system was coughing up some new age sungura that I couldn’t recognise.

Despite what has become of the music, sungura had a good run. It had its three golden ages: the era of Kasongo Band and Sungura Boys, the era of Zhakata, Khiama Boys and Leonard Dembo, and the last phase of Alick Macheso and Tongai Moyo. There are no new Chinyanis or Ephraim Joes to nurture a fresh new cadre of sungura artists. Nobody has the patience for all that anymore. The live acts struggle to fill small, dingy venues. Nobody cares what album covers look like anymore. Big sungura bands, with their three guitarists, bass men and drummers, are deemed unviable, a waste of money in an age in which radio-quality music can be made by a single teen in a bedroom studio. Most crucially, just as sungura once spoke for the masses, today’s young have found their own outlets in new genres, such as Zimdancehall music. The country has changed, moved on. End of story.

Tileni Mongudhi, writing early in 2018 in the Southern Times newspaper of Namibia, describes how Zimbabwe’s sungura remains hugely popular among some communities in his country: “It has become folklore that among the Aambadja people who live in northern Namibia and southern Angola, when a man is courting a Mbadja girl, she will ask him three questions to determine whether the man is worthy of her time. The first question is whether he owns a bicycle, the second question is whether he owns an Omega cassette player, and the third is whether he owns a John Chibadura album.”

I like to think that, just as Central Africa gave its rumba to East Africa to forge its benga and its kanindo, and just as East Africa gave us its benga and kanindo for us to make our sungura, maybe we too have passed the torch, and given our sungura to others. So, perhaps, this is where some will begin their own story.

This and other stories available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.