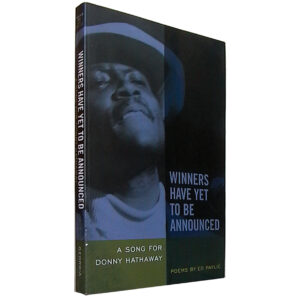

by Ed Pavlić.

Harmony Holiday

Ricochet Editions, 2014

“Where material is absent, dialectics is groundless.” – James Snead, “On Repetition in Black Culture”

“For me to go find my father,” writes Harmony Holiday, “has meant to fall in love or infatuation with black artists who are a lot like him. This search morphs from being about one man, to being about at least three, from being about my vigilance to being about where it meets with blindness, from being about Saturn to being about Venus, from being about love to being about where love equals desire: a rare alcove of beauty, truth, and the riveting unknown.”

The result is a portrait of the artist’s daughter, as artist, of course, in scripts of a mind that feels it can’t live without knowing and fears that it won’t be able to survive what it finds out. Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues is a double album. Both discs are meditations on, solicitations, and, I think, by turns evasions of, the myth of the masculine, the colour of the sun on the dark side of the moon. There’s a voice here, irrepressible. There’s a fearlessness, too, singing the borderline between bravery and fatality. Talent in buckets left out under the eaves during spring in Monsoon, Mississippi. Myth, Marx, Freud, Joseph Campbell, Robert Graves and a ceaseless roll call of black voices. Galaxy upon galaxy of black sounds swallowing each other, colliding, then getting up and tip-toeing out before the others wake up. Light in this double-sided collection appears in flashes, a blade of sun slipping through the crack in the blinds on the morning before the night after which it was too late not to care in the first place. Sight caught second hand, so that the present is already a day late, a dollar short, and even reading the lips of the person after next – the one that got off the train in front of ours at our stop, which we missed – is hindsight.

On the ground somewhere, or at least in Los Angeles, are Harmony Holiday and her mother and her sister Sara. Up ahead, in hindsight, is Jimmy Holiday, the poet’s father, a real life soul singer, writer, legend, cliché, lover, father, abuser. Jimmy Holiday was born in Sallis, Mississippi in 1934 and died in Iowa in 1987. Harmony Holiday writes: “A yellow girl enters the red wheelbarrow and the chickens gotta go.” Jimmy’s daughter’s double book doesn’t give the details so much as it re-mythologises “particulars” stolen from William Carlos Williams’s upturned wheelbarrow (someone had to kick those damned chickens out of the yard, after all – give her that) of modern poetry. “Say it, no ideas but in things,” wrote the good doctor in Paterson. Yeah, I know. Fuck that. Harmony Holiday writes: “The feminine side of the black myth is a lot like me, fatherless, full of the father”. The voice in the double book morphs into an Orpheus in “the transcendent festival that is Black life in America”.

Mr Holiday was a real talent. He wrote songs for himself, soul/rhythm and blues from the American South. He recorded his first song, “How Can I Forget”, in 1963, with Everest Records. It’s the kind of soul music that, for some reason, heard in 20-20 retrospect from the 21st century sounds like somehow one imagines it sounded, first, as heard by an 18-year-old Bob Marley, then just beginning to record as well. Judge Not. As Ms Holiday reminds – or forewarns – us throughout, “imagining is remembering”. To wit: danger, danger, “–ring the alarm”, something may still depend upon – well, maybe the Fu-Schnickens, “wo-o, hey, hey”.

Jimmy Holiday also wrote songs for very very famous and rich people, such as Ray Charles, “Hey Mister”. He wrote “All I Ever Need is You” which Ray also sang, as did Sonny and Cher and Kenny Rogers and Dottie West. Possibly most famously, Holiday wrote “Put A Little Love in Your Heart”, which Jackie DeShannon recorded. If you’re old enough to remember the late 1960s and early 1970s in the US, the latter performance is about as good a place as exists to go for a “message” song that claims a slogan (“Put a little love in your heart, and the world will be a better place”) that the performance can’t possibly vouch for. Cue strings and trombones. It’s no use, it still sounds like “I’d like to buy the world a Coke… ”

This isn’t Jimmy Holiday’s fault. It’s a good song, the kind of song with a genealogy that knows way more than the song admits. It’s interesting that the song hovered in the top five on the US pop charts and topped the South African Hit Parade in the summer of 1969.

In The Fire Next Time, which topped bestsellers lists in the year that Jimmy Holiday made his first record, James Baldwin argued that, in black music, so much depends upon “something tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged”. This is absolutely undeniable in “How Can I Forget”. There’s a deep historical echo beneath the song of forgetting failed or refused. The voice plays it cool in the verses over xylophone, strings and tympani. Narrative. But, a raw scream breaks into the chorus, the authority of the key question. How, indeed – “How?! How, how?” Maybe remembering is forgetting failed? Or refused. Of course, the pop charts in the 1960s and 1970s rather preferred sweet to tart, and single- if not simple-minded to double-edged, if you please, “a red wheel” keep on turning.

Meanwhile, on the world ground, scorched beneath the cloudless Los Angeles sky of the pop charts, apartheid reigned, a thing the Vietnamese called The American War raged on, expanding, and US cities smouldered following another season of unrest and assassinations. Ideologues such as Mulana Karenga proclaimed the obsolescence of the blues, poets such as Amiri Baraka (possibly the brightest star in Ms Holiday’s pantheon) publicly derided writers such as James Baldwin (another touchstone for Ms Holiday) while privately soliciting favours from him, at the same time proclaiming, in pieces such as “The Revolutionary Theatre”, that “these will be new men, new heroes, and their enemies most of you who are reading this”, and, in poems such as “Black Art”, the need for “poems that shoot guns” and “wrestle cops into alleys”. Say it, no ideas but in revolutions.

Meanwhile, on the life ground, Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues paints in thrashes a story of double deals in business and raw deals in the emotional pantheon of life that left Jimmy Holiday a broken man and a violent husband and father. A story – absent the wheelbarrow, chickens driven out of the temple – the poetry re-frames in a split cosmos of New Age religion and world mythology: Saturn, Venus, I Ching, Tao, Atum-Ra, and “the Porgy archetype”. And, I take it then, a whole lot depends upon the “transcendent festival” in black art (if not life) that will provide Jimmy Holiday’s questing daughter with ingredients for a “mythorealism of [her] experience”, as she wonders whether or not “violence is mandatory on the continuum of expressivity”. This isn’t easy money in a world marked by “the interchangeability of tenderness and terror, exhilaration and dread, black and white”, in the life (even if it is mythoreal) of a character who, at times, “can’t remember the hidden edge of her own skin” and who suspects that “sometimes understanding is fatal”.

So there it is, playing chicken with going chicken-less but, I think, still “glazed with rain/water”. Say it, no ideas but in things. Richard Pryor made fun of black men “Always holding on to your dicks.” He followed with: “White guys always ask, ‘Why do you guys hold on to your things?’… You done took everything else, motherfucker.” And Jimmy Holiday’s question, double-edged and authoritative, asks “How Can I Forget?”

In Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues, Harmony Holiday’s rain-glazed voice shuffles a deck in which all the face cards are fathers, a genealogical quest in the Nietzschean sense of a search for the origins of value, if not values, in a world where some facts are fatal, and where smiling faces tell lies, and she’s got proof… Amen.

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop. Copies coming to your nearest dealer now-now. Access to the whole issue and Chronic online archives is available for $28 for one year or $7 for a month.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurenga-shop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button] [button link=”https://chimurengachronic.co.za/online-subscription” color=”black”]Subscribe to the Chronic[/button]