Sometimes you take off because you don’t want to still be around when people come back to their senses.

Knock-kneed, I was never built for running, but I knew that you run faster when racing other people than when running on your own. With a little imagination and no small amount of effort, I straight away pitted myself against an imaginary Usain Bolt right in the middle of the squatter camp. The camp, an extension of the township, had twice been bulldozed by local authorities in the past, but always returned bigger, energised with a great desperation amongst its dwellers, who were angrier and more disqualified from regular society than before.

Instead of streets and avenues in the rectangular form that is favoured by town planners, the camp was only one dusty nameless road that meandered and criss-crossed itself many times over. Sometimes the road took a sharp bend when it was blocked by a cluster of tin-roof houses, but even on such bends, I was flying at full pelt, and with a little more effort my heels would have been touching the back of my head. I was breathing down Bolt’s neck.

I could only maintain my pace for so long against a super athlete. When my legs could not cope, I lost the strength to restrain myself and started laughing my head off. I did not know why I was laughing. It just felt right. I could not say why the situation that I had fled was funny but I knew it was. Like reading a poem: the good ones speak to you before you have even understood what they are all about.

I had to run. I started again, at speed but laughter was getting in the way. My vision was distorted with tears and the camp appeared to be getting bigger, sprawling downhill so that the township that I was trying to get to appeared to float further into the distance. I knew the township well, since it was where I had grown up. But I knew little about the squatter camp. I had never been here before.

Every time I turned around I saw in the distance behind me the plume of smoke coming from the address I had just fled. An US$85,000 car was ablaze and the boys were being forced to watch the spectacle from the comfort of a shack whose value could not be more than the Justin Timberlake leftover French toast that was snapped up on eBay.

I was back in my home country – taking a break from Bay Ridge, New York City, where I was a cab driver – and coming to the realisation that my circumstances were impossible to shift, or that I was human and therefore too weak to overcome them. After holding out for years to the very limit of my strength, I had fallen into a place where a downbeat outlook was my perennial baseline. I had lost my shadow and longed for the kind of cathartic moment that is unavailable to people like myself. I also loathed my home country now, maybe because its own failures and unrealised potential resonated uncomfortably.

Exhausted with laughter, I stopped running. I shuffled through the squatter camp, my jacket soaked in the armpit and the skin on the insides of my thighs raw from rubbing against each other. I started to think about a fare that I picked up one afternoon: from the backseat, he said that if you took a 50-year-long aerial footage of NYC and played it speeded up to reverse play completely in an hour, then you would learn that money is a relationship, the thing by which you daily exchange things, not the thing for which you exchange things. Money had been a big problem for me, ever since I started living in New York.

By the time I was heading towards the marshy gumtree plantation separating the camp from the township, this episode was already assuming the nature of an antidote against all the pent-up frustration that I had carried from New York. I had lost Sharai two hours back at the funeral, when she abandoned me with the boys.

This trip back home was the first time I had seen her in years. A couple of days before the funeral, the three Moyo brothers asked her to come to their step-sister’s funeral. “As if it was an invitation to a tea party,” is how she related it to me. She laughed. We had a soaring catch-up conversation about school days and how back then the Moyo brothers and their lot would never waste a glance on any of us. Now one of the twin brothers had been trying to get into Sharai’s knickers for over a year and would not take “no” for an answer.

Because normal rules did not apply when it came to the Moyo boys, Sharai thought it a good idea to ask me to accompany her. The Moyo brothers, spendthrift, could always be relied on to provide spectacle. Styling it up.

Initially, I was not keen on the idea. I did not wish to come into contact with the Moyo boys again. I had refused their repeated Facebook requests to be friends. I still had not forgotten about the twins making fun of the fact that the only reason we were at the same school was that my uncle was a janitor there, which meant my fees were waived on charitable grounds.

After their very public excesses and with the enemies circling their VIP mother, the Moyo boys were only one public scandal away from disaster, Sharai thought. War vets, perennial supporters of the government since the farm invasions, were already calling for the boys’ mother to resign from the cabinet and her children’s public displays were giving her enemies one more stick with which to strike her. If she can’t even control her own children, how can she lead one of the most important ministries in government?

The boys’ relationship with their mother had just taken a major knock over their insistence on attending their step-sister’s funeral, to which they’d invited Sharai. Any PR disaster had the potential to bring down the already wobbly government, which could not survive if the boys’ mother was pushed out, Sharai thought. The boys’ father had died in a car crash last year and their mother did not want them to go rushing to honour a woman who was likely a gold digger posing as their step-sister, a step-sister who had only surfaced after the death of the boys’ father.

Emerging from the gumtrees, I was home and dry. I took a potholed street in the direction of my aunt and uncle’s house. I was possessed with a vast spirit of play and in order to expunge residual trapped energy, nearly talked myself into a stupid stunt on the edge of the dilapidated road: a couple of cartwheels ending with a tidy backflip of the sort footballers execute after a stunning goal.

When i lift my head to look around one more time, the funeral has descended into disarray. There are all kinds of mourners, from the sincere, god-fearing folk and the sort that are drawn by a morbid curiosity, to the pragmatists with good antennae for a free lunch.

A WhatsApp message from a number I do not recognise lands on my phone the moment I switch it on. For a moment I feel ashamed to be looking at this unedifying photo while standing next to Sharai. She still has the capacity to be enthralled by the unremarkable, it seems. Mentally, I checked out of here ages ago. Even this moment, it’s hardly an interesting sort of disorder now that the Moyo brothers have been cast into a state of confused, inarticulate contrition, which is not their style.

You could have been forgiven earlier for thinking that the Moyo boys and their entourage came to the funeral just to stream it live on Facebook or something. They and their groupies are a restless, noisy lot and arrived with that sort of enthusiasm. For a funeral.

To see them roll in was to witness a flock of birds land on a tree just before sunset: mock disputes, genuine squabbles, and plain mindless chatter of boys in baseball caps and barely clothed girls. Now some of these hangers are slinking away to wait at the car park; they are ashamed for the Moyo boys. A humble man in a bin man’s attire has turned the whole funeral upside down and disappeared.

I missed a lot of the beginning because I was not paying attention. Sharai brings me up to speed: the coffin was about to be lowered into the grave when the man, holding the hand of a six year old girl, pushed his way from the back of the crowd of mourners. He looked just like any of the neighbours and community leaders who had come forward to say their words on the edge of the grave. Even his opening line was correct until you noticed the sharpness with which his finger pointed down at the coffin: “I know this woman and I’m going to tell you the truth.” This, I did not miss.

All three Moyo brothers were still pointing their phones at the man before it sank in that his impromptu, passionate speech was not a Pentecostal-type effusion of sorrow over their dead half-sister. Finishing his ultimatum with a despotic hand gesture, the man turned around, whisked the little girl off the ground and threw her onto his back. Then he stepped off. He was out of the cemetery before anyone had broken the spell.

Finding him in the sprawling squatter camp where he is supposed to live is going to be fun.

The Moyo brothers have never had to handle ultimatums before, certainly not one from someone in a pair of overalls with reflective straps around legs and arms. It’s the bin men’s attire.

The funny thing is that I should receive the WhatsApp message at this moment, when the Moyo brothers are at sea.

Since returning home I have seen plenty of images like this one. Images that speak to grinding poverty in Africa south of the Sahara. But this one is in a category of its own: the camera person zoomed in on an unsuspecting young woman’s posterior as she bent down to drink water from a standpipe. She could easily be one of our township girls. A good chunk of her dress is missing, as if it was rescued from a termite nest; half her bum and knickers are exposed and the caption above the image reads “Keep voting ZANU–PF if you want to show us everything in the end.”

It’s the fifth time I’m receiving the same image today. Earlier in the morning, the Moyo brothers, after learning from Sharai that I was around, added me to their WhatsApp group, “The Boys.” It was an odd gesture. They had also shared the image shortly after adding my number to their group and that all but confirmed everything I suspected about them.

“Put that thing away please,” Sharai says, and I slip the phone into my breast pocket and fold my arms. I can’t stop thinking about the image and the boys.

The boys, they are rudderless. A single glance at them and I find myself unable to stop thinking that this must be what the terror-struck villagers of Gwata looked like when they became the objects of a prank by a squad of bored soldiers. They used the butts of their rifles to frogmarch the unsuspecting peasants to what looked like a convincing site of slaughter and informed the villagers that anyone who could put on a convincing dancing display would be freed.

Turns out it’s impossible to dance when you’re terrified. The higher functions of the brain shut down, leaving only the banal human animal thrashing about, stripped of all psychological complexity.

The boys have slipped into this state in the absence of a gun. The twins, Tanaka and Tawanda, bear faces struck blank with terror. They came wearing what is now their signature sartorial style since they launched as a rap duo: identical watermelon-pink suits and designer smoking pipes. They look like consummate Congolese sapeurs. Thankfully, given the context, no fan is trying to take a selfie with them.

Two men have already started shovelling earth into the grave. Mourners are dispersing. All three Moyo boys are still rooted to the spot now that even the simple task of putting one foot in front of another has suddenly become too complicated.

“At last the boys are beginning to understand,” Sharai says, digging into my ribs with her elbow. Her gesture does not go unnoticed: Melusi, the eldest of the boys, is looking at us.

You would think that the boy’s dead sister’s only child, a boy who is barely 17, would come forward to support his uncles since he is the root of all this. But no, he is nowhere to be seen.

“I know this woman and I’m going to tell you the truth,” the man said of the boy’s mother. His delivery was striking. “I know her well because I have seen what she was capable of. This woman carried the darkest and most gnarled of hearts.”

Last year, the man’s daughter fell pregnant by the dead sister’s son. As per custom, the girl’s family ordered the girl to pack her bags and go to the boy’s family, expecting that the boy’s family would formally return with the girl and boy in order to start righting wrongs. But the boy’s mother would not even allow the girl into the house, left her to spend the night on the doorstep and in the morning opened the door and emptied a jug of urine on the girl’s head.

To have your daughter spend the night on the doorstep, while a grown-up woman in the house is busy pissing into a jug all night for the purposes of humiliating and scaring her away.

It was obvious that after God had finished making all the beautiful plants and creatures on earth, he was left with an evil lump of clay which he threw into a pit, only for Satan to find it, make the black mamba, the toad, other evil creatures. “…and this woman!”

Worse still, the deceased woman had contributed nothing towards the care of this child. “Not even one red cent.”

This was the point when the man, grim and looking for terrible words, appeared to break the fourth wall in order to address the Moyo lineage: he was giving them until sunset to find him, or else all of them, one by one, were going to start falling like flies. In fact, he was disappointed their step-sister had died before he was satisfied with his revenge; if it was possible, he’d pursue her into the spirit world to finish her off there.

Mourners shall not eat, he declared, until the matter was resolved.

They believe in science, the boys, and not the black magic with which their new enemy is threatening their entire family. But it’s obvious they also know that black magic works even if you don’t believe in it. They don’t want to die and have long put away their smart phones. Or maybe they’re just trying to contain this problem and stop it becoming a problem for their mother.

We are about to slip away when one of the twins, Tawanda, casts his gaze in our direction and makes eye contact. His face is already lit up and I cannot just turn away and bolt.

“Should we go and hold their hands as per custom,” I ask Sharai. Her eyeballs bulge out of their sockets. Before I can think, she has turned on her heel and started walking away. I don’t know what it would say about me if I followed her. After floundering in awkwardness on my own, I step towards the boys.

Tawanda throws himself around my neck. His twin brother joins in the hug fest, which seems rather too enthusiastic to be credible. We have not seen each other in years. I am surprised there seems to be genuine affection in their hugs. The three brothers accept my condolences and sympathies and even Melusi seems more positively disposed towards me. One thing leads to another and before I have thought of an exit strategy, I find myself, unintentionally, inside their car.

Melusi is driving, Takura in the passenger seat and Tawanda and I in the back seat. Part of the brothers’ entourage is in a seven-seater van, whose driver still hangs his head out of the window while talking to Melusi about leading the way. With the lot in the van is a god-fearing church lady who knows where the boys’ adversary lives. She initially gave copious directions that none of us could quite follow. The boys begged her to come with us.

But before going to the aggrieved man, we must first go fetch another man, who is elderly enough to come with us and take the role of go-between. The man is not related to the boys; it’s an unheard of way of doing things, but the boys never do things the normal way.

As soon as we start rolling, the boys and I start reminiscing about the good old school days. The fact of me having spent all these years not in some fancy New York job, but driving a cab kind of falls out of me. At this revelation, the boys fall silent and exchange looks. Then they burst out laughing. It’s a moment of release, coming after the funeral experience, and a breakthrough into honesty between us.

“Now you have to drive us, man!” Tawanda cries. “Melusi let him drive! We must be driven by a New York taxi driver! We have to!”

We all laugh. I’m hoping Melusi will disregard his brothers, but he reluctantly brings the vehicle to a halt on the side of an open drain.

I have not even put on the seat belt and Takura has slapped a wad of notes on my thigh.

“There, chibhanzi for you!” he says triumphantly. Like big time bank robbers, they may no longer be capable of demonstrating affection in any other way but with money, it dawns on me. Sometimes I hate disappointing people. You could say I’m a coward, but I am not a bad coward.

“Don’t just stare at me like that! Take it!” Takura says, “One thousand US dollars. That’s fair for a drive by a New York taxi driver, no? Or are you now one of those people who are embarrassed by money?”

I can’t change what’s happening around me and therefore must change how I regard it. One thousand US dollars – it’s nearly the price of my budget air ticket. I’ve lucked out.

“Maybe you guys should write a new rap number, “Bankrupt Yourself or Die Trying!” – it looks like that’s what you’re angling for,” I say.

“That will break the internet!” cries Tawanda. He thinks it’s a great idea and is already tapping it into his phone to make a note.

Their car is the most retro thing I’ve ever been inside, let alone driven. “A taxi driver from Trumpland driving me in a Cadillac! That’s a lyric,” Tawanda laughs. Their music career and celebrity status are things they bought for themselves from the money that their father made from the Marange diamond rush before he perished in a car crash. He missed out on the US$15 billion diamond money that mysteriously went missing from government coffers last year.

Soon enough “taxi driver from Trumpland” has evolved into “Mr Trump”. It feels churlish not to play along. I must put in some emotional labour in order to be convincing.

“You’re going to wipe the floor with that man who ruined your sister’s funeral,” I joke. We laugh over the possibility of me stepping in if they can’t persuade the elderly man who is earmarked for the role of go-between. After all, the aggrieved man is only a bin man. A mabhini.

“I’ve got the best words ever!” I exclaim. “Nobody knows a mabhini better than I do!” The twins slump sideways with laughter. They dig this Trump style of addressing issues, not in the narrative but the declarative. I never made any effort to memorise these lines; it therefore comes as a surprise to realise that a whole repertoire has been sloshing around at the back of my head.

The supposed go-between man is also supposed to be a traditional healer. By the time we get to his address, I’ve heard enough about him to know that he is only a healer in the same way Idi Amin was “Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular”. He’s sporting a Red Sox cap, beat-up Converse All Star trainers on his feet and has clocked quite some mileage on planet earth. He needs a walking stick to help him along.

You’d think that this fraud of a man and the money-flashing boys are perfectly matched, but it does not take long for the man to take offence at the notion that the boys can come here and take him to wherever they please for a few pieces of silver. They must think him a lightweight, he says indignantly, waving a hand to signal the meeting is over.

For the next ten minutes or so, the boys bid against themselves, progressively raising the money offer from US$200 to US$3,000, on condition that he dresses up respectably if he is interested in the money. Soon it is obvious that it’s not the money that the old man finds unattractive, but the circumstances of the task: they are ripe for someone to be hacked to pieces in a dusty yard in broad daylight.

In the car, the boys are speechless. The lady who was in the van has left, after hearing the old man corroborating her fears. At least she scribbled a rudimentary map with directions to mabhini’s home before walking away. I wait for the boys to gather themselves before I start the engine and screech away. The driver of the van also takes off and follows us.

“Listen, I can do this if you want me to.”

“Do what?” Melusi’s tone is hostile.

“I’m only trying to help.”

The boys’ tempers are fraying. It does not help that none of them is even bothered with the task of navigation; I’m having to do both as we enter the squatter camp. They’re shouting at me every time I take the wrong turn. It is here that you think, fuck a duck, what am I even doing here? I’ve been taken so far out of myself, I no longer know if I am John or Jabulani. Yet, I do not recoil. It’s inexplicable. I’ve never bought into all that spiel about the heart having its reasons of which reason does not know. Nonsense.

“Listen, I can do this if you want me to,” I say again. “I can talk to the man for you guys if you want.”

For about a minute, no one says a thing about my offer.

“Sorry, that’s a stupid thing to say. I take that back.”

“No, no. It could work!” Takura brightens up.

“No, I don’t think it will work. Think of it. You need someone who can earn respect before even uttering a word. Mabhini is unlikely to take anyone of my age seriously and may even take it as an insult.”

“Think outside the box man! Think like a music promoter. You’re our promoter!” Tawanda too has pivoted from bad temper to tremendous enthusiasm.

“You mean like I’m unscrupulously negotiating a gig for you?”

Takura giggles.

Melusi, who has been silent until now says: “I think it’s a stupid idea.”

“Why is it stupid?” Takura is almost hurt.

“Are you mad?”

“Ok, give us your better idea then, Melusi!”

A better idea from Melusi, there comes none, but silence.

“I’ll talk to the man myself then,” Melusi says.

“Really? Just like that? You, Melusi, walking up to the man’s front door and saying ‘let’s talk’?” Tawanda claps his hands satirically.

“You can’t do that, Melusi. That’s disrespecting the man. You will stagger out of his door with an axe sticking out of your head,” I say.

Now the boys start cracking jokes about the whole thing. As if it’s an abstract problem of which they are mere observers.

“Why are we terrified by this man?” asks Melusi. “It’s not our problem that the man did not get on with our dead half-sister. Why are we troubling ourselves over this?” He is starting to talk like someone with a gun in his pocket.

“What about your mother?” I remind him. “Are you sure this will not turn into a problem for her if you guys don’t kill it off right now?”

None of them answers.

By the time we locate the bin man’s street, a plan is already taking shape. Just in case the feared man takes offence to us parking right outside his gate, we park a little further down the road and plot.

I will go out alone first to introduce myself to the big man. I am going to be an African-American; if our adversary can be forced to speak English instead of Shona, we’ve won the first round. This is my idea and not the boys’, but they’ve bought into it with no small amount of trepidation. The risks are great, but the rewards are greater if all works out, I say.

They get it that my task is to manoeuvre the big man onto territory that he’s not too confident operating on. The same Zimbabwean who speaks Shona becomes an entirely different person when he speaks English – he will even walk differently when speaking English, we all agree.

I will keep the big man captive in unfamiliar orbit, close all escape routes for the duration of the negotiations. If he escapes to his regular orbit, someone’s trousers are going to rip as abrupt flight starts.

“We Zimbabweans are the original cultural relativists. We are terminally inclined to be more forgiving towards a foreigner than one of our own,” I reason out aloud. “That is why our history is marked with incidents of us being cleaned up by foreigners who come here and are allowed to operate outside our cultural regimes, which impose all manner of obligations on everyone else. Next thing we know, the foreign dude has helped himself to the land and gold deposits and no one can figure out how it happened.”

I feel good and the boys are wracked with nerves. They’ve already pulled out of somewhere a bottle of Armand de Brignac “Ace of Spades” champagne. Apparently, it’s Jay Z’s favourite. It’s supposed to steady their nerves. In spite of, or maybe because of, this opulent display, the boys look adorably vulnerable. I have never held their future and their mother’s in my hands.

“You,” I say to Tawanda.

“I’ve got a name!” he explodes. “Why you suddenly started calling us you this, you that? What’s that all about?”

It happens sometimes: you neither notice nor know why you suddenly stop calling someone by their name. This is when you just feel you’ve got fish blood flowing in your veins. Your energies are tied up in making sure that no matter how much things tilt around you, they do not touch the thorn that sticks out of you: a vast, quivering inner insecurity that must be squashed, pushed way down deep in order for you to be able to present as extraordinarily free of humanly vulnerabilities.

“Let’s go through the plan one more time,” Takura says. Inside, he must be piano-wire tense. “So what are you going to do?”

“You talking to me?”

“Who else?”

“Well, I’m gonna go in there, keep mabhini captive in the English-speaking domain. And then, when I get bored, just let him escape into his Shonahood and then he will be free to come after your reprobate asses!”

A beat or two pass before you all burst out laughing.

“Ok. The nuclear option is to offer the man one ballpark figure to take care of everything. More money than his ass has ever seen in his lifetime. I don’t expect him to immediately understand that offer. He’ll probably be like those Sioux Indians, to whom the notion that European settlers wanted to buy the Sioux’s land seemed so ludicrous they had to ask the prospective buyers if they wanted to buy the sky as well. But once mabhini and I are on the same wavelength, I expect a quick attitude adjustment. The rest should be easy and you guys will soon be on your way to your sister’s house to start partying with the mourners.”

Now they start to talk about food. Huge quantities of food have apparently been prepared. The boys are suddenly conscious of their hunger. It’s the cue you need to step out of the car.

You slam the door, determined not to overthink. You’re determined to immerse yourself in the primal rush of blind impulse and are already beginning to feel, inside you, the coming to life of a spring from which extraordinary things flow.

At the gate, you’re met by a young woman who must be the daughter who had pee poured on her head by the boys’ sister. She’s accompanied by the toddler that the man brought to the funeral, and asks if she can help. You’re discovering the surprising experience of committing oneself: when you’ve wholly committed yourself, you enter a new zone and, with each breath, are super aware of every bodily sensation. You are alive and present to every moment – it’s as if parts of your brain that you have never used before have suddenly sprung to life. The young woman’s father, sitting on a bench chatting to two other men, gets up and disappears into the house before his daughter has even turned around to inform him you’re here. The father’s two friends follow him shortly after, as does the daughter, and you’re left standing in the yard with just the toddler who continues to look up at you with bright eyed curiosity.

Another woman, who must be the daughter’s mother, emerges. She asks me to take a seat on the bench and wait. She drags the little girl into the house and you’re left alone but not for long: there out of the corner of the house, a small face, peeking. Teeth are missing from her mouth, which makes for a winning smile.

“I can see you” you say.

“No you can’t!”

“Yes I can!”

She comes out into the open now, the hem of her dress lifted up over her head.

“I still can see you!”

“I’m a bat now!”

“But I can still see you!”

“But it’s nighttime. You can’t see at night!”

“I can still see a bat at night.”

“Do you know many things that move at night?”

“Yes.”

“Name three.”

“A car, a bicycle and a train.”

“No! No! No!”

“Well, then why don’t you name them?”

“Bats! Rats! And… sekuru!”

“What does your sekuru do when he’s moving at night?”

“I don’t know! Ask him!”

The boys come to mind and, briefly, you’re scared by whatever it is, the nameless thing that your heart craves. Yet you’re sensing this rare sort of uncertainty that only ever appears when everything is possible. You have not felt like this in a long time.

“Look, this is Mary!” the little girl says, pointing to one of the hens inside a coop. And you know at once she’ll never be able to eat Mary. Not easy eating an animal when you’ve given it a name.

This and other stories available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

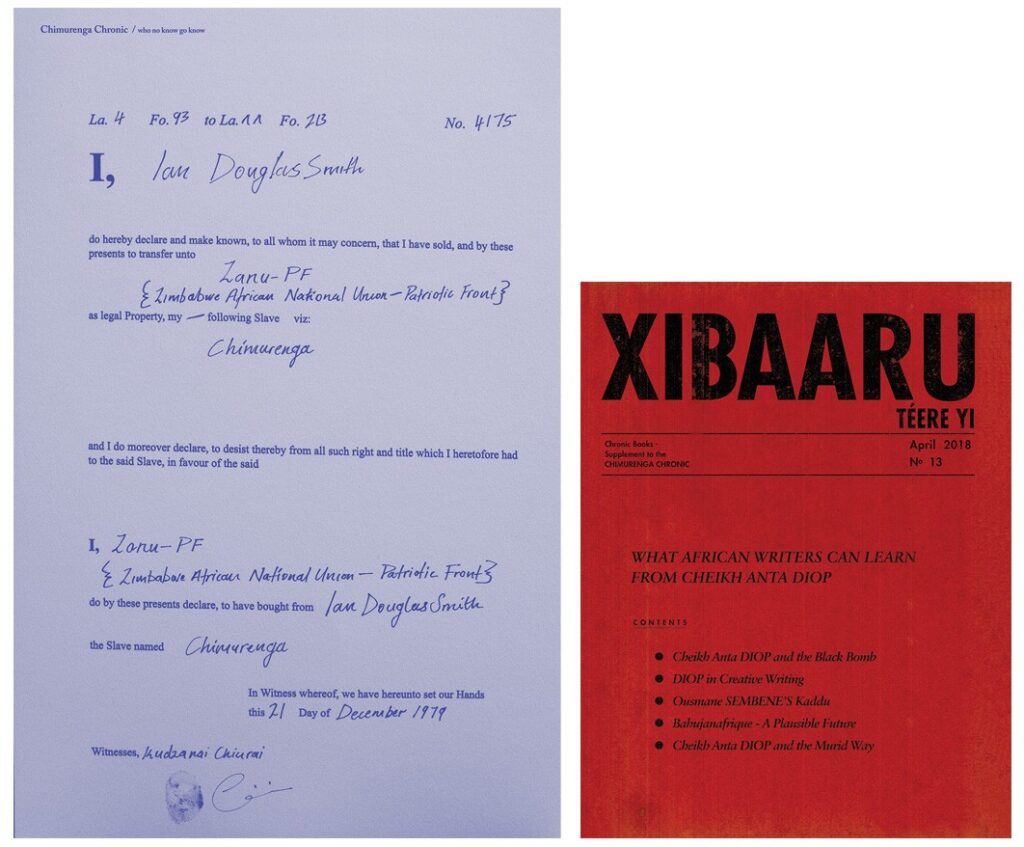

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop or visit Chimurenga Factory at 157 Victoria Road, Woodstock.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work