Zimbabwe’s economic crises have played out in the press, in political and parliamentary exchanges, and on the streets, among the people most immediately affected. At a glance, it appears like a no-win situation. But, foreign companies, especially South African retailers, are making a handsome profit from Zimbabwe’s demise. Simbarashe Mumera boards the night vendor bus from Harare to Musina and gets an introduction to who owns whom in the dollarised economy.

It starts before the journey starts, with a simple ritual performed weekly before the cross-border bus commences its 1, 200 km round trip to or from the border town of Musina, South Africa. A man dressed in formal attire enters the bus and delivers a prayer for the journey before he invites the travellers to sample his wares: Bibles and other Christian reading materials.

As he performs, the passengers, most of whom are traders, slowly trickle in, lugging folded saga bags and luggage carriers. Outside, more travellers are scattered around the Road Port Bus Terminus in Harare, awaiting departure. Near the entry gates and along the adjacent road, are the money changers, trading various currencies, but mostly South African Rands and US Dollars for Zimbabwean bond notes. It’s an ordinary day in the capital.

Over the past few days, I have immersed myself directly in this narrative through the business of night vending. Fascinated by the spirit of the open evening market, I have decided to join the traders on a trip to the border. I am seated next to Amai Mona, a night vendor who sources goods from Musina for resale in Harare. She has agreed to allow me to travel with her so I can gain first-hand experience into the intricacies of the trade. We sit in an awkward silence. She is a Christian, eager to share religious teachings. I am not. I have indicated this to her, hence the silence. She has already briefed me on what to expect on our journey. We’ve engaged in the usual chit-chat about the situation in the country, the new president and so forth. Only a few hours into the journey, we have run out of things to say.

Malaichas and night vendors

Late in 2016, the Zimbabwean government introduced Statutory Instrument (SI) 64, a protectionist legislative tool that prohibits imports of certain goods that are being produced locally. This measure was meant to revive a struggling local industry which, after decades of economic turmoil had almost collapsed. The Government hoped that foreign producers who shipped goods to Zimbabwe would be encouraged to open shop locally or, at least, finance local production through loans and other forms of support, as had happened in the tobacco farming uptake. Should the need to import restricted products arise, a permit could be obtained from the Ministry of Industry and Commerce.

What government did not anticipate was Zimbabwe’s appetite for foreign goods, especially from South Africa. The expected boost in local production didn’t happen. Locally produced goods turned out to be slightly more expensive than their imported counterparts and, in some cases, their quality was inferior. In addition, most Zimbabwean families living in South Africa continued to bring goods back on their journeys home, making the legislation difficult to implement. Larger, more established stores had restricted access to imported products, birthing the early morning and night vendor trade that I was now a witness to. Malaichas – individuals or networks that provide unregistered courier services transporting goods from South Africa to Zimbabwe – have flourished and illegal cross-border traders are numerous.

The night vendors trade mostly in household products, blankets, and phone accessories. According to Amai Mona, it is as simple as sourcing products for resale from Musina. Prior to our trip, we contacted a malaicha by the name of Mthunzi. “You always have to talk and make prearrangements with a malaicha before you leave. He is the one that will help you out,” cautioned Amai Mona, “Do not ever try to organise a malaicha after you have reached Musina or Beitbridge. There are a lot of thieves in that trade that will rob you of money or stock.”

Much of our journey is uneventful. The bus costs a meagre US$10. When we get to the Beitbridge bus terminus, the malaicha, Mthunzi, comes to fetch us and a few others. He drives us into South Africa and on to Musina. For the rest of the morning, he assists us and a few other traders as we buy our stock, regularly advising which items will be expensive to get across the Zimbabwe side of the border. Mthunzi loads up his truck, charges us for the crossover and leaves. On average, he charges 10 per cent of the total cost of a trader’s products for his services. Duty on grocery items and clothing is usually 40 per cent of their value, but you pay the malaicha a fraction of that.

Together with Amai Mona, I get on a taxi back to the border where I disembark. Amai Mona proceeds to the Beitbridge bus terminus where she will wait for the malaicha to come through and drop the stock. They will then load the stuff on a bus destined for Harare, pay US$10 for the luggage and soon be on their way. It’s a pretty smooth process.

Like many other traders, back in Harare, Amai Mona will, over the course of the week, sell her purchases at pop-up markets. Their preferred spots include taxi ranks, pavements and, in some cases, closed road lanes, all space where they catch their customers as they return home in the evening. Depending on sales, she will soon schedule another trip back to the border. She is one of many. Sales are good. Vendors are cheaper than retailers, by as much as 50 per cent. Indeed, even conventional retailers have also become customers to some traders, and South African manufacturers have unwittingly found eager distributors.

As in much of Africa, Zimbabwe’s markets and informal vendors are not part of a marginal sub-economy. They are the means through which much of the population sustain their livelihoods. Not only do they provide a vital source of income, they also create a distribution channel that gives people access to some of their most basic supplies.

The real beneficiaries

In a recent twitter diss, Fadzayi Mahere, a prominent Harare lawyer and politician, took a swipe at the new administration’s handling of the cash crisis. She compared it to that of the main opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) back in 2009, when they were in charge of the Ministry of Finance in the Government of National Unity. When you go the distance on that twitter thread – ignoring the arguments about who dollarised the economy – you pick up a sense of despair about Zimbabwe, again finding its economy gripped by a critical lack of liquidity and badly depleted foreign currency reserves. This only a hundred days after the swearing-in of a new Zimbabwean president, who has promised quick fixes to the problems crippling the economy.

It is almost a decade since Zimbabwe officially abandoned its own currency and adopted a multi-currency basket under the Short-Term Economic Recovery Program (STERP) – slightly longer than with the informal market and most of the general public who started using foreign currency to conduct their transactions in the early 2000s.

For a country long shunned by the international community, the widespread availability of the US dollar generated renewed global interest in Zimbabwe’s economic affairs. Those in the Zimbabwean diaspora, who had left the country in biblical numbers in the 2000s, became a source for foreign currency for most families in the country. This trend created a chain of foreign currency “reserves” in the hands of the general public, even though the government and formal financial institutions did not manage to bank these funds. The hyperinflation of the 2000s also encouraged locals to keep their savings in US dollars. If anyone received payment in the local currency, the first thing to do was to change it into the more secure dollar.

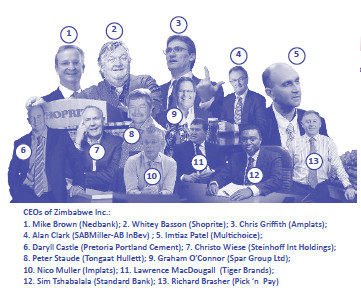

At the turn of the decade, when the country officially adopted a multi-currency regime, it took off largely on the back of the foreign currency stocks already circulating and the savings (virtual reserves) held by the general public in hard cash. Zimbabwe suddenly had an influx of foreign companies, almost all from South Africa, that quickly opened up shop and began a process of mopping up the US dollar, a currency performing better, at the time, than the South African Rand. They quickly grabbed the low hanging fruit and were rewarded handsomely, when most local players were still scrambling around trying to find their knickers and recover from a decade of devastating economic downturn. Many South African entries established operations in cities close to the Zimbabwe border and others created synergies with local companies in pursuit of the US dollar. They did so without ever inducing any form of industrial recapitalisation or long-term investment.

Certainly, South African companies were not the only ones that benefitted, but because of their proximity and association to and with Zimbabwe, they benefitted most. You cannot miss the irony, given the slights that Zimbabwe and its government endured the last two decades, which these same companies drove and animated through negative press, as well as by their flagrant lack of long-term commitments to Zimbabwe’s economic growth. During that period, Zimbabwean products were overvalued by an estimated 15 per cent compared to similar US Dollar-priced products using the purchasing price parity (PPP) model. A product that would cost the equivalent of one dollar in an economy such as South Africa on a PPP model, was trading at approximately US$1.15 in Zimbabwe, presenting the perfect arbitrage opportunity on the part of South African players.

The relief provided by the multi-currency system was fleeting, but it raised vital dividends for South African companies. Zimbabwe’s economic and financial struggles were ameliorated by dollarisation, which in turn accrued largely to foreign companies. Dollarisation, due to the performance of the currency at the time, meant reduced competitiveness for local products internationally and most importantly, locally. While exports became more expensive, imports were cheaper for Zimbabweans. Products coming from South Africa found a bigger market in Zimbabwe. Moreover, the higher prices charged in Zimbabwe on the back of the strong dollar and overvalued products profited companies importing goods from South Africa. The economy did not favour local companies, given a lack of lines of credit at the time. In addition, reduced interest rates meant reduced incentives from local financial institutions to loan out money. At the same time, the higher than average regional lending rates meant financing for local companies from foreign sources was more expensive. They therefore struggled to obtain new equipment or service the old, which increased the cost of their products.

Dollarisation, interestingly, also eliminated exchange rate risk and/or losses to the benefit of foreign South African economic players who were using a weaker rand but were earning in the reserve currency just across the border. Price stability increased economic predictability and hence investor confidence but, again, this worked in favour of foreign companies that had the ability to move swiftly to fill the gap left by non-productive companies. These profits were of course not retained to increase deposits for generating loans, nor were they reinvested to improve products or to grow the economy. Profits were repatriated almost immediately to South Africa.

The new savings, accumulated by the public, reinforced a culture of spending in an economy dominated by South African corporations. The general public still lacked confidence in the financial system and kept most of their foreign currency transactions circulating outside the formal financial sector.

The government’s decision to issue 99-year leases of land and to reserve the right to cancel leases on non-performing farms, led to a reluctance, on the part of financial institutions, to accept the new leases as collateral. Large tracts of farmland remain unfarmed as a result of inefficiencies and a dearth of credit for new farmers, which created food shortages, stimulated demand for foreign food products, and caused speculation in prices. This has largely worked to the benefit of South African financial institutions that, through the network of previously dispossessed farmers and their local banking units, found neat and crafty ways to provide credit an d support to local tobacco farmers through a process of contract farming.

Financial assistance to tobacco farmers through contract farming from Nedbank, a South African bank, in the form of secured loans via its local subsidiary, MBCA Bank, boosted tobacco production in Zimbabwe to the pre-2000 levels. On the surface, Zimbabwe owes its salvation to South Africa, but an understanding of the contract farming model suggests significant benefit to the funder. The contractor provides not only the funding for farmers, but also the general tobacco market. They are the primary buyer of the tobacco at their set prices. The contractor, after purchasing the product from the farmer, goes on to sell the product on the world markets which perform much better than a local market could in Zimbabwe. To add insult to injury, South African services such as broadcast channel DStv have grown to become the biggest earners of the foreign currency in Zimbabwe. In his monetary policy statement in 2017, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe noted with concern that DStv subscriptions, which amounted to US$206.66 million between July and December 2016, were second only to fuel procurement with regards to the foreign currency spent. This was more than the country spent on the procurement of vital raw materials, machinery for the manufacturing industry, and telecoms equipment.

It doesn’t stop there. People have grown accustomed to exchanging their dollars and crossing over to South Africa for shopping. Thus, in late 2016, when the government instituted Statutory Instrument 64 to limit imports that were entering Zimbabwe, cross-border travellers retaliated by torching the customs and revenue services warehouse at the Beitbridge border post.

Zimbabwean consumers might benefit through the unsolicited distribution, but the South African producers have most to gain from the invention and agency of the traders. These small-scale night vendors are merely the atomised expressions of a larger set of economic, political and social circumstances that work together to foster a boom in South African commercial expansion into Zimbabwe, usually to the detriment of local trade and industry.

[hr]

This and other stories available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurengashop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button][button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/subscribe” color=”red”]Subscribe[/button]