Jeremy Weate explores the cultural politics of the petro-based economy in Nigeria, where crude as commodity has perpetuated ethnic divides and the illusion of development and modernity through a national pastime of forgetting. He asks: what culture and what memory will be left of oil, after it has gone?

The culture of oil that has shaped the production of images in and of Nigeria since the late 1950s is now drawing to a close. The world is turning to energy independence, to gas and to renewables. No one has any essential need for the “sweet” (easy to refine) crude of the Niger Delta any more. The political class, drunk on its proceeds, has yet to notice. We’re in that cartoon moment when Bullwinkle stands frozen beyond the cliff top and is yet to plummet. Government (no matter the replaceable names) keeps signifying according to a grand sense of self: in the size of overseas delegations, in decadent plans for shining Lagos enclaves, in dreams of Dubai planted on a Sahelian soil. No one has a strategy for a future beyond oil, or for a climate baked too hot because of it.

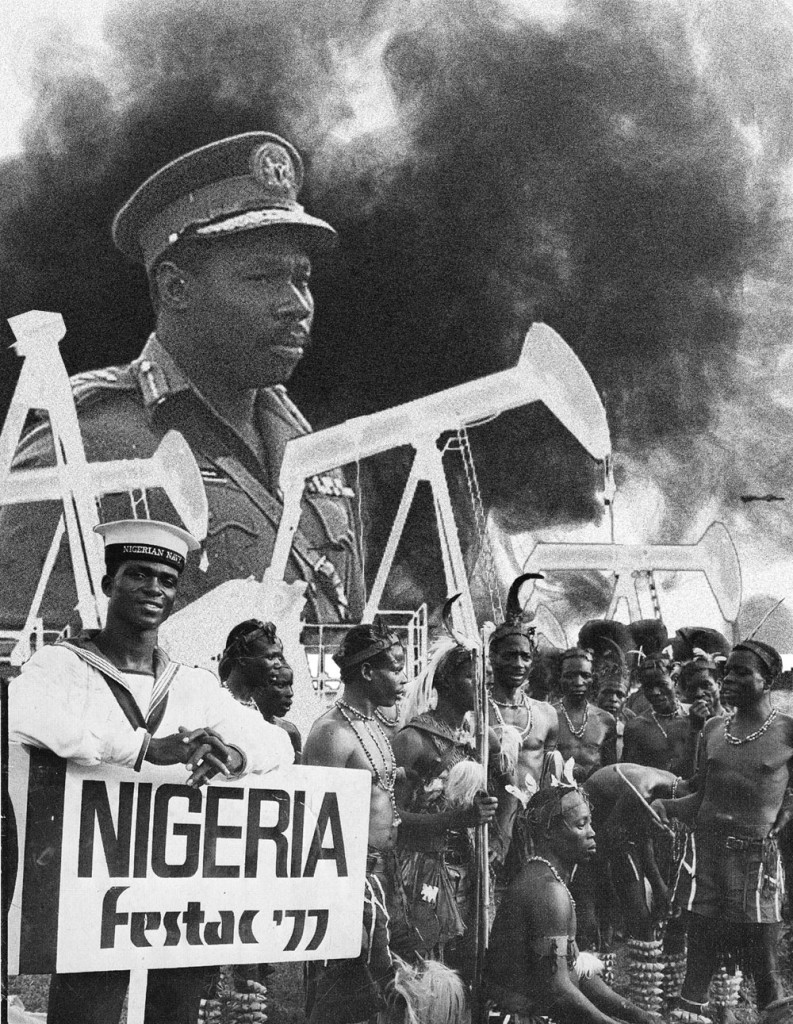

We are witnessing a decades-long dilution of the moment of intensity that was the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, popularly known as FESTAC, in 1977 (the first took place in Dakar in 1966). In Andrew Apter’s magisterial analysis, The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria, the festival was both an allegory of the oil boom and a chimera. Underneath its homecoming celebration of African culture, through his analysis, FESTAC reveals itself to have been an illusion of development and modernity. Anchored by an emerging concrete infrastructure amid an excess of signs, FESTAC showed Lagos to be in a state of hydrocarbon-induced semiosis. Images were produced which had no substance behind them; in a reversal of Marx, the fetish was commodified. It was an era when Nigeria’s problem was not money but “how to spend it” (in General Gowon’s famous formulation from a few years previously), of owanbes without why and of limitless lace.

We are witnessing a decades-long dilution of the moment of intensity that was the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, popularly known as FESTAC, in 1977 (the first took place in Dakar in 1966). In Andrew Apter’s magisterial analysis, The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria, the festival was both an allegory of the oil boom and a chimera. Underneath its homecoming celebration of African culture, through his analysis, FESTAC reveals itself to have been an illusion of development and modernity. Anchored by an emerging concrete infrastructure amid an excess of signs, FESTAC showed Lagos to be in a state of hydrocarbon-induced semiosis. Images were produced which had no substance behind them; in a reversal of Marx, the fetish was commodified. It was an era when Nigeria’s problem was not money but “how to spend it” (in General Gowon’s famous formulation from a few years previously), of owanbes without why and of limitless lace.

Today the Gulf States, from Dubai to Abu Dhabi, are using oil wealth to position themselves as cultural hubs via biennales, festivals, art fairs and new international galleries. To begin to unpack this apparent link between oil and cultural florescence, we need to understand in more detail what is so special about oil. The black gold is incredibly profitable compared to, say, most mining products – apart from precious stones. The profits from oil are so large they are called “rents” by economists. Oil is so profitable mainly because it has a very high energy-returned-on-energy-invested (EROEI) ratio. The energy used to pump oil out of the ground (and refine it/transport it to the consumer) is far less than the energy that the finished product (gas/petrol) provides. This EROEI ratio is much higher for oil than, say, for solar panels or nuclear energy. There’s a plausible argument that suggests that the planet’s burst in population growth in the past 50 years or so has been driven by the economic growth delivered by the energy efficiency and profitability of oil (and all the downstream products made available by oil). This also implies that towards the end of oil (beginning from the time when oil gets more expensive to take out of the ground) we will see a steady slump in global population and economic growth.

This means that from a cultural perspective, oil takes the form of a general surplus which has an amplifier effect on the host culture. Distortion is commonly associated with amplification, and this is no different in the case of FESTAC, where the signal of various Nigerian/African cultures was amplified to create at least an element of noise. This surplus/amplifier/distortion nexus goes a long way to account for the strange relationship between oil and culture we see not only in Nigeria but also in the Gulf states. The difference with the Gulf is that there is very little obvious diversity in the host cultures – in comparison to Nigeria – and therefore the cultural events there often rely on cultural imports. In both cases, it’s almost as if, alongside economic rents, oil creates “cultural rents”, which take the form of grandiose events that lack any substance or ground. Oil creates cultural simulacra, in short. We should nonetheless remember FESTAC as a historical event in the cultural history of oil, worth recalling because it is a lesson in taking culture seriously.

It will take some time for the braggadocio signifiers of petrofest Nigeria to fade from expectation, at home or abroad. Cloth is key to maintaining prestige. Taken just a few months after FESTAC 77, that image of then-president Obasanjo in his finest, most starched agbada, standing proud next to Jimmy Carter, is the sartorial norm that President Goodluck Jonathan – with his Niger Delta brass-buttoned etibo – attempts to replicate.

In Jonathan’s case, the image is entirely empty of content. There is no observable Nigerian foreign policy in the active sense – of Nigerian diplomats in Washington, London or Paris lobbying for a position on particular issues agreed in advance in Abuja (or via the AU in Addis). Foreign policy relations – at least with the West – exist in the passive mode of attending meetings when called to do so, meeting-the-headmaster style. This reflects the fact that Nigeria is almost completely dependent on crude oil sales for its foreign exchange earnings and government revenue. There is no leverage to drive a robust forward-thinking foreign policy stance. Things are slightly different at the regional level, with Nigeria’s heavyweight status ensuring that the country dominates discussions in ECOWAS, and plays a strong historical role in security/military issues in West Africa. Interestingly, regional concerns relating to Boko Haram seem to be centred on Chad rather than Abuja, although no one seems to have asked why.

The most significant story to tell about global politics and Nigerian oil currently is that, as of July 2014, Nigerian crude exports to the US had stopped completely. This has yet to be fully appreciated and analysed. In the context of an already lukewarm approach to US-Nigeria relations, the US no longer buying any Nigerian oil means the latter is even less geopolitically significant than previously. The US gave up on Nigeria being the base for its African military command centre years ago, and conveniently views Boko Haram as a local issue which offers no threat to US interests either on- or offshore, so no need to sell weapons either. Combined with the general slump in global demand for oil, Nigeria faces a mounting economic crisis. The need to diversify government revenues away from oil has never been stronger. Whoever wins the February 2015 election has to do things differently and challenge the non-innovative mafia style of politics in Nigeria. This involves not only looking forward but also backward.

Unless there is a change in direction, little will remain for future Nigerians to remember of the FESTAC period, apart from fading cloth and the images and sounds stored digitally in archives elsewhere. True, FESTAC lives on as the name for a run-down suburb on the western edge of the city and in the grandchildren of FESTAC – the annual Lagos Black Heritage Festival and Abuja Carnival. But how many today associate Festac town with FESTAC 77? Nigeria can no longer aspire to be a centre for black diasporic pride – the end of the journey for intimately held dreams of return. In the absence of monuments, monumentality takes the form of a forgetting, or an erasure. It is as it ever was.

Earlier periods in Nigerian history are not stored in space either. By an accident of geography (coastal marshes), there is no slave castle as a lodestone for traumatic memory, and yet millions of Africans in the New World came from Nigeria, traded in Lagos or the creeks of the east. What commemoration does exist is pathetic; one might visit the museum in Badagry and hold up a rusting chain (Marlon Jackson’s £2.4 billion resort with its shops, a slave ship replica, condos and Jackson Five memorabilia did not come to pass). As for the longer-lasting Trans-Saharan trade, its memory is no more architectural than shifting sand in the desert, far north of Kano.

What has not taken place, either through FESTAC or through its diluted replications in our time, is a thoroughgoing reworking or recalibration of the role of historical/pre-colonial cultures in the present, or as a programme or manifesto for the future. The 2014 Lagos Black Heritage Festival took place at Freedom Park on Lagos Island and focused on retrieving cultural traditions of music. There is an understanding of the need to support the retrieval of almost-forgotten cultural traces for contemporary reworking, but the drive to create a stronger influence of the past on the present and the future is quite weak. Good intentions are blown away by the wind. Much has been made of Africa rising and Nigerians returning from the US. The early wave of returnees actually came during the telecoms boom (which started with MTN setting up in Nigeria) in the early 2000s. They were economic migrants, mostly with little interest in Nigerian culture and largely philistine in outlook. Some came from the US, some from the UK. My personal experience has been mostly negative – embellished CVs and little appetite for engaging empirically with local markets to understand consumer/customer behaviour, thanks to a holier-than-thou outlook. Things, however, are changing. There is another wave of cultural returnees. This has made Lagos a much more interesting place, with venues such as Freedom Park hosting the monthly Afropolitan event, events at the Life House and the Centre for Contemporary Art. The eastern part of Lagos Island, Onikan, is likely to develop as a cultural quarter with projects such as the conversion of the old print works into an art/event space. Look at the fact that Frank Agrario (of The Bank) moved from San Francisco to Lagos, or check the work of Lagos sound artist Emeka Ogboh. And experientially, I always love going to the Shrine. The vibe is exciting and the Area Boys become an aestheticised form of menace. Neither Femi nor Seun’s star burns nearly as brightly as their father’s, but it would be extraordinary if they did, wouldn’t it? There is a lot more going on in terms of contemporary culture in Lagos than perhaps ever before, but what’s missing from this is a real sense of history, a serious rememoration and reworking to ensure that Lagos doesn’t become just another hub in an increasingly uniform global cultural market.

The autochthonous and collective urge for a nation to remember is generated in part by a unifying narrative – shaped by shared victories, or through shared suffering. In Nigeria there is little of that, not even in its regions. National culture, which could play a vital unifying role by supporting a sense of shared histories and cultures, often simply defaults to the bare form of supporting the national football team during the Africa Cup of Nations or the World Cup. The question of a national culture is especially important in Nigeria, where the petro-based economy has helped to fragment any sense of national identity by sedimenting ethnic/regional divides (via competing claims for oil rents). We urgently need to transform the focus from the ethnic/regional to the national. This has to go beyond annual events. There needs to be academic research into various Nigerian cultures to unearth their complexity (and not reduce them to caricature), and these need to be studied by school children and be part of the curriculum. The research needs to be centred in Nigeria, not in far-off universities. The work of a Nigerian cultural modernity lies ahead and cannot be achieved by festivals alone.

FESTAC was funded by revenue windfalls from oil, just as the current ethnic and religious tensions in Nigeria are effectively financed by oil. In both cases (then and now), the cultural/identity distortion is driven by oil rents. The popularity of Boko Haram in the North East, for instance, comes from the fact that many of those living there feel abandoned by “Abuja”, and also feel that the wealth of Nigeria is never distributed to the north-eastern regions of the country. Boko Haram is first and foremost about extreme poverty in the midst of plenty, rather than a religious issue all the way down.

It’s interesting to note that Kalakuta Republic was sacked shortly after FESTAC (leading eventually to the death of Fela’s mother). At the very time FESTAC was happening, there were concerted attempts to kill Fela. It’s as if the attempt to create the effect of an official national culture also required killing off the unofficial national culture. Herein was its greatest failure. Even today Nigeria’s most famous 20th-century son still has no public memorial in his home city. There were just too many women, too much herb, too much pidgin, too many Macaulayist bowties maintaining the rejection.

In Nigeria, historical opinions are set apart from each other like tectonic plates. Every now and again there is an earthquake that exposes fissures over roles in the civil war or corruption in the post-independence years, or provokes harangues over who was the worst dictator. There is nothing to be built in commemoration on land that is constantly shifting.

The oil that remains is quietly shipped away, or is stolen, or leaks deep into the already blackened soil. Yet still government lives beyond its means, and produces nothing. What culture and what memory will be left of oil, after it has gone? Will there (at last) be new ruins, half in the sea, beyond Bar Beach? What will the beautiful Nigerians not yet born make of this time that is passing and of this substance that confused everyone?

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

This story features in the new edition of Chronic Books, the supplement to the Chronic. Through dispatches, features, interviews and reviews, we explore the reach of public relations and petrodollars.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop. Copies coming to your nearest dealer now-now. Access to the whole issue and Chronic online archives is available for $28 for one year or $7 for a month.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurenga-shop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button] [button link=”https://chimurengachronic.co.za/online-subscription” color=”black”]Subscribe to the Chronic[/button]