Ibrahima Wane

Translated by David Leye

When it was published by Présence Africaine in 1954, Cheikh Anta Diop’s Nations nègres et culture acted as a trigger for many black intellectuals, particularly young African students in France. Recognizing their own significance, leaders of the Federation of Black African Students in France (FEANF) distributed Diop’s research on African languages in order to incite emulation. The Grenoble FEANF chapter was extremely keen on cultural issues, and thus made its contribution. United around a core group made up of Cheik Aliou Ndao, Assane Sylla and Abdoulaye Wade, its Senegalese members worked on a pamphlet that eventually became famous: Ijjib volof (Wolof Syllabary).

Ousmane Sembène led the artistic front, striving to produce films that come “as close as possible to reality and to the people”. The titles of his films are revealing: Borom sarret, Taaw, Niaye, Xala. Soon, the movement to reclaim African languages spread to Senegal where, during the 1968 strike, students and teachers demanded a reform of the educational system (which thus far still bore its French footprint) and the Africanisation of school and university syllabuses. On 24 July 1968, the government took a first step, passing a decree pertaining to the transcription of national languages. The next step saw the establishment of the Alphabetisation Directorate in 1970. But scientific research does not wait for the administrative machinery to catch up. Pathé Diagne eloquently demonstrated this with back-to-back publication of Anthologie wolof de littérature (Dakar, IFAN, 1971) and Grammaire de wolof moderne (Paris, Présence Africaine, 1971).

In order to provide the missing link, Diagne and Sembène, along with a few other activist intellectuals, decided to launch Kàddu (“Speech” in Wolof), the first Senegalese newspaper printed entirely in an African language, in order to provide information to peoples marginalised by French print media. For its promoters, Wolof, being the most widely used language in Senegal, was an ideal channel through which to put the richest information and knowledge within the reach of an entire nation, thus giving people the power make up their own minds on any topic. The first issue was published in December 1971 as a mimeographed newsletter. Reference to this monthly publication appears in Ousmane Sembène’s novel, Xala, as well as in the eponymous film adaptation. A revealing dialogue occurs between the businessman, El Hadji Abdou Kader Beye, and his daughter, Rama, a student:

El Hadji stepped behind his daughter and looked over her shoulder.

– What is this?

– It’s Wolof.

– You write in Wolof?

– Yes, we published a newspaper: Kàddu, and we teach it to whomever is interested.

– Do you think that this language will be used by our country?

– 85% of people use it. They just need to learn to write it.

– What about French?

– A historical blip. Wolof is our national language.

El Hadji smiled and turned away towards his wife.

Kàddu sought to provide a space for awareness and sharing. All sorts of issues were raised through the opinions presented, as well as information on the country and the rest of the world. Kàddu also tackled politics, religion, history, art, sports, and health. Further sections dealt with poetry, cartoons, games, and readers’ letters. The first issue had articles about the Nobel Literature Prize winner Pablo Neruda and Pablo Picasso’s 90th birthday. Issue 3 had in-depth reports about contemporary struggles in Southern Africa (Rhodesia, Namibia, Mozambique, Angola, South Africa). Then followed a special issue (March-April 1972) presenting an assessment of the situation in Senegal after over a decade of official sovereignty. In Issue 6 (September 1972), six pages were dedicated to Kwame Nkrumah’s struggle. The newspaper added three other languages as it matured: Pulaar, Sereer and Mandinka. Regularly devoting several pages to writing and comprehension, it became a vehicle for African language literacy for many urban youth.

More than a mere editorial committee, Kàddu was a research, study and experimentation group reflecting on a broad spectrum of profiles and backgrounds: Pathe Diagne (linguist), Ousmane Sembene (novelist and filmmaker), Amadou Top (IT expert), Wagane Faye (lawyer), Maguette Thiam (mathematician), Samba Dione (linguist), Ben Diogoye Bèye (journalist and poet), and Alpha Walid Diallo (visual artist). They were Marxists, Maoists, Cheikh Anta Diop disciples, and even Leopold Sedar Senghor disciples, who shared a common belief that development was impossible to achieve in a foreign language. The newspaper thus provided a federating framework; in other words it showcased a patriotic and progressive front in a single-party context. Indeed, when it merged with PRA-Senegal (African Gathering Party), the Senegalese Progressive Union (UPS), then in power, proclaimed itself the “unified party of the masses”. Opposition movements and parties were all operating underground. Tolerated by the state, Kàddu was one of the few legal platforms of resistance at the time.

More than a mere editorial committee, Kàddu was a research, study and experimentation group reflecting on a broad spectrum of profiles and backgrounds: Pathe Diagne (linguist), Ousmane Sembene (novelist and filmmaker), Amadou Top (IT expert), Wagane Faye (lawyer), Maguette Thiam (mathematician), Samba Dione (linguist), Ben Diogoye Bèye (journalist and poet), and Alpha Walid Diallo (visual artist). They were Marxists, Maoists, Cheikh Anta Diop disciples, and even Leopold Sedar Senghor disciples, who shared a common belief that development was impossible to achieve in a foreign language. The newspaper thus provided a federating framework; in other words it showcased a patriotic and progressive front in a single-party context. Indeed, when it merged with PRA-Senegal (African Gathering Party), the Senegalese Progressive Union (UPS), then in power, proclaimed itself the “unified party of the masses”. Opposition movements and parties were all operating underground. Tolerated by the state, Kàddu was one of the few legal platforms of resistance at the time.

Following growing public interest, it was not long before a clash occurred. The initial warning came in 1972 when President Senghor wrote to his prime minister on the subject of national languages. He insisted on establishing an advisory committee that would be tasked with tabling a segmentation method for Wolof sentences. As a pretext for this measure, the president referred to alleged errors he identified in Kàddu, which, in his view, required urgent action from the government to put order in the sector: “As local media and literature in national languages are developing in our country for the first time in any significant way, authorities cannot tolerate that anarchy and confusion prevail in an area as sensitive as language or that an illegal national language transcription system is created and developed at the whim of the authors’ personal choices and improvisation.” Thus, a decree was passed in 1975 on spelling and segmentation rules in Wolof and Sereer. This provision clashed with transcription rules defined by linguists and was met with indifference. To enforce it, the government passed a law in 1977 requiring any publication in a national language to submit to control by a committee and imposing severe sanctions – ranging from fines to jail sentences – on “those who, through public broadcasting, intentionally violate the rules governing the transcription of national languages, as defined by legislative and regulatory provisions”.

This unprecedented move had major consequences. Ousmane Sembène’s just-completed film, Ceddo, could not be screened in Senegal’s cinemas because of the title spelling, which did not comply with the presidential decree’s guidelines. In outrage, the film maker wrote a “Letter to all Senegalese men and women and to the President of the Republic of Senegal”, in which he decried the inconsistencies of the official text and the inequity of the decision to ban his film. Editors of And Soppi, a monthly publication founded by Mamadou Dia, Senegal’s first prime minister, and his friends from PAI-Senegal (Senegalese Independence Party, an underground organisation), felt compelled to comply with the new standards in order to safeguard their “Magazine of political views and information”. The spelling Andë Sopi was used for the magazine’s title.

Cheikh Anta Diop, the political director at Siggi, the central organ of the Democratic National Gathering (RND), refused to make this concession. Rather than twisting the spelling, he preferred to change the magazine’s name: “The law… by the national parliament upon request by the President of the Republic puts an end to any possibility for national languages to develop under Senghor’s mandate: this decision will leave its mark in the legal annals. It is the first time that a man, haunted by the ghost of his own national culture, goes to such lengths to asphyxiate that culture… Neither the Government, nor SENGHOR has the authority to impose on us an obviously wrong structure for our mother tongues. Therefore, we would rather change the name than back down on such a crucial issue of principle. SIGGI (raising the head, getting up) becomes TAXAW (standing), which is even more radical. We can thus sidestep the legal trap that they wanted to spring on us.”

This controversy ended only when Léopold Sédar Senghor stepped down from office in 1980 and when more consensual transcription decrees were adopted. Kàddu was at the forefront of the fight against a form of censorship that almost annihilated the protracted efforts of experts who were drafting rich pedagogical materials at the Fundamental Institute for Black Africa (IFAN) to support the use of national languages in schools and promote the spread of bilingualism (mother tongue or regional vernacular and European language).

For seven years, Kàddu was a vehicle that was at once political, scientific and artistic. It enlightened the minds and fuelled the aspirations of journalists and poets. Its experience inspired many other initiatives. One of the best known is Lasli-Njëlbéen, a bilingual Pulaar/Wolof newspaper founded by Seydou Nourou Ndiaye, who had written for Kàddu as a young journalist and was a regular client of the Sankore bookstore opened by Pathé Diagne at the end of the 1970s. A disciple of Cheikh Anta Diop, Ndiaye was committed to the fight for African languages. Launched in 1998, Lasli-Njëlbéen became a publication of reference thanks to the quality of the writing and production.

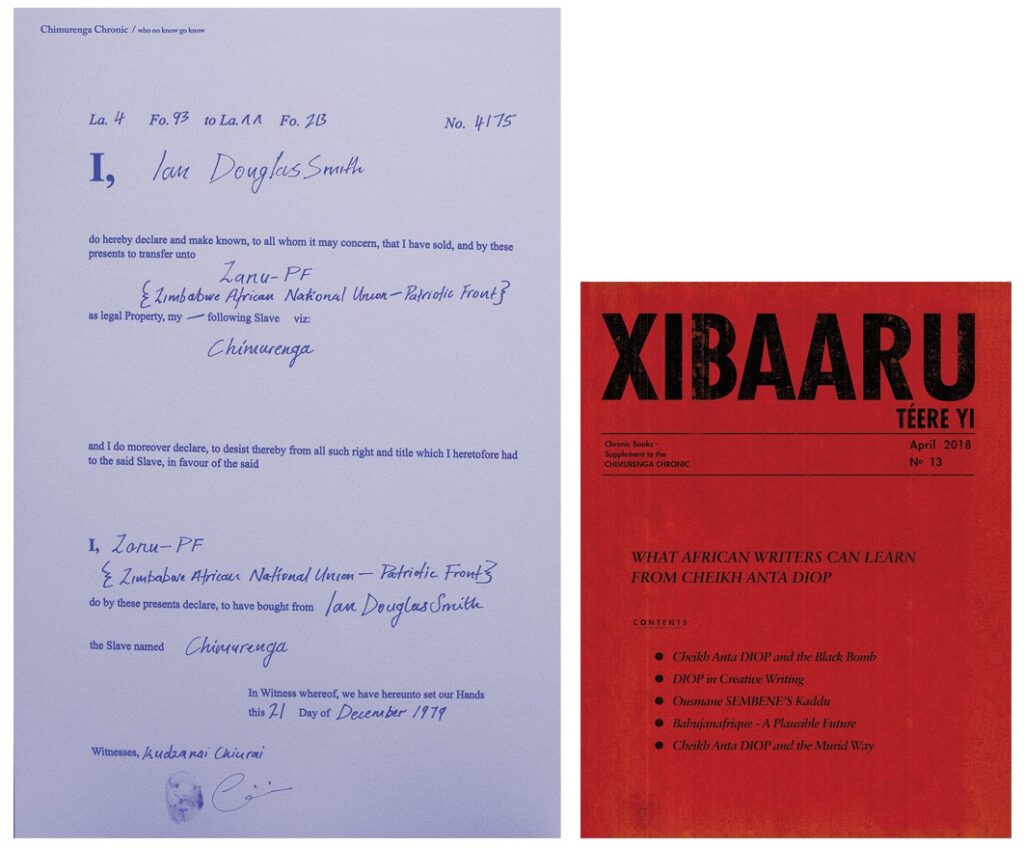

This and other stories are available in the issue of the Chronic – The Invention of Zimbabwe which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop or visit Chimurenga Factory at 157 Victoria Road, Woodstock.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.