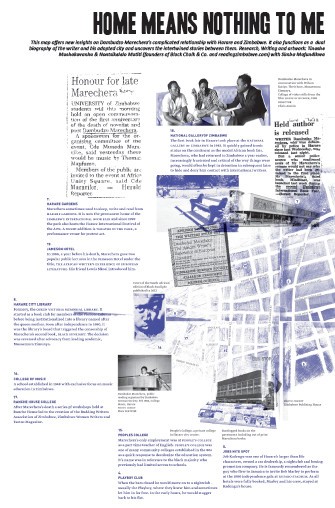

Tinashe Mushakavanhu talks about his mapping project, “Home Means Nothing to Me,” which documents the life and movements of author Dambudzo Marechera in the the city of Harare between 1982 and 1987 upon his return to Zimbabwe after forced exile in the United Kingdom. Created in collaboration with Nontsikelelo Mutiti, with whom his runs Black Chalk & Co. and readingzimbabwe.com, and Simba Mafundikwa, the map appears in full in The Invention of Zimbabwe, the new edition of Chimurenga’s Chronic.

This piece was shortlisted for the 2018 Brittle Paper Awards which seek to recognise the finest original pieces of writing by Africans published online. Read more on the awards and see the other 31 nominated pieces.

There was a lot of dislocation, people have come back into the country, a lot of trauma, war trauma, so everyone has a story and they just didn’t know how to share the stories. And Marechera decided to be the story doctor.

Home & Away

The title of the map comes from the film, House of Hunger (see below). There is a scene where Marechera is going back to Zimbabwe and he is talking about his relationship with home, and his ideas of home. The title makes sense because Marechera didn’t have a strong relationship with Harare during exile. It wasn’t home. He was a small town boy, lived in Harare for two months for university, got expelled. And so his relationship with Harare actually only starts when he comes back. It’s an exiled relationship. Coming back home to a home that was never a home.

I think the bulk of major scholarship misreads Marechera. Everyone assumes his book House of Hunger to be set in Harare. House of Hunger is actually set in a small town in the east of Zimbabwe. And so primarily the idea of this project was to challenge that sort of popular misreading of Marechera. We wanted to look at him in this place and trace him or follow in his footsteps. It is both faithful and fiction, necessarily because it also plays around with the mythology of Marechera. So we are following Marechera to the places that we know we can encounter him, through his own writing and on readings of the others talking about Marechera.

Man & Mythology

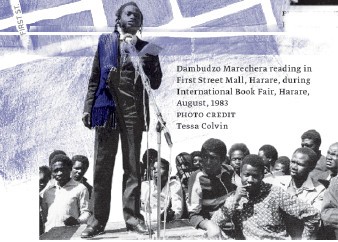

I’m curious about Marechera’s influence. In 1982 he is still a new writer. His books haven’t really been widely read, almost no one has actually read him. So what people know about him are from the stories, the rumours, in newspapers and through word of mouth. They know that he is the writer who went to Berlin without a passport. He is the writer who tried to burn down Oxford. So people are reading the mythology around him, not the actual books. Even within his lifetime. And that is the frustration he expresses in Mindblast because he is confused with his mythology. He’s got this popularity, he comes back, people are terrified of him, people don’t understand what he does. And so in a way, he starts interrogating that. I think he adopts this idea, the idea of the writer he ends up as. He performs it. And I think in a lot of ways he over-performs the mythology. I’ve interviewed his contemporaries like Stanley Nyamfukudza – they were together at Oxford – he said to me, “I’m surprised with how people pursued Marechera back then. For us he was just like a teenager, very shy, you really had to coax him. If you wanted him to speak, you really had to force it out of him.”

His books haven’t really been widely read, almost no one has actually read him. So what people know about him are from the stories, the rumours, in newspapers and through word of mouth. They know that he is the writer who went to Berlin without a passport. He is the writer who tried to burn down Oxford. So people are reading the mythology around him, not the actual books. Even within his lifetime. And that is the frustration he expresses in Mindblast because he is confused with his mythology. He’s got this popularity, he comes back, people are terrified of him, people don’t understand what he does. And so in a way, he starts interrogating that. I think he adopts this idea, the idea of the writer he ends up as. He performs it. And I think in a lot of ways he over-performs the mythology. I’ve interviewed his contemporaries like Stanley Nyamfukudza – they were together at Oxford – he said to me, “I’m surprised with how people pursued Marechera back then. For us he was just like a teenager, very shy, you really had to coax him. If you wanted him to speak, you really had to force it out of him.”

Harare & Zimbabwe

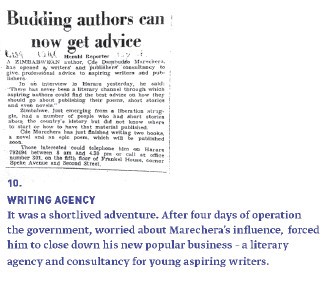

In the map, we tried to let the person lead us to the mythology. That’s how we worked on the project. So the idea was to locate Marechera in actual places. And obviously within that the mythology. For me, the person was in front of the mythology in this particular project. I think there is also something that has happened with Marechera where he has been stripped of his identity as a Zimbabwean, as an African. So the scholarship around him now describes him as a universal writer, as an international writer. So he’s no longer rooted in a place. And the idea was to try and locate him in a place and see what narrative emerges.

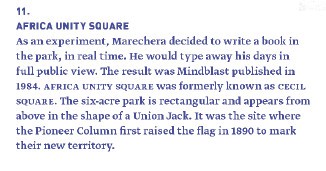

In the map, we tried to let the person lead us to the mythology. That’s how we worked on the project. So the idea was to locate Marechera in actual places. And obviously within that the mythology. For me, the person was in front of the mythology in this particular project. I think there is also something that has happened with Marechera where he has been stripped of his identity as a Zimbabwean, as an African. So the scholarship around him now describes him as a universal writer, as an international writer. So he’s no longer rooted in a place. And the idea was to try and locate him in a place and see what narrative emerges.

Harare and Zimbabwe merge in Marechera because of his own experience. Before exile, Marechera’s experience is in a small town, in Rusape at St. Augustine’s, Penhalonga, where he went to school, so in the east of Zimbabwe. He leaves Zimbabwe, comes back and his experience of Zimbabwe is just Harare. So he interacts with Zimbabwe from Harare. And in a lot of ways nothing has changed in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe has always been Harare-centric. So the Zimbabwean experience has always been centred around Harare. So, you know, Bulawayo has its own fascinating history but in the big scheme of things it’s a peripheral, footnote to the history of Zimbabwe. So locating Marechera in Harare was also trying to complicate that because in a way, yes he has become an everyday man, or an every man, but then we are also forcing him into a space that is repulsive to him. So we’re trying to play around with his identity as a writer. Is he a writer from Harare or is he a writer from Zimbabwe? So while it was locating him in a space it was also poking fun at that idea of labeling a writer or locating a writer in a specific place.

Community of Writers

Marechera himself says, “If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you.” He refused nationality and national identity in and insisted he belonged to a community of writers. And I think partially his alienation with Harare comes in him not finding a community of thinkers, an intellectual community that understands what he is trying to. And so at the end of the day he ends up identifying with the Beat Generation. The journal section in Mindblast echoes so many of the statements from the Beat Generation – Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac. I think he was lonely. And I think Mindblast was a cry of loneliness. So he is back in this community, he wants to identify with the community but the community shuts him out. But at the same time all his work – House of Hunger is about a community, in as much as there’s alienation, there’s loneliness, but the story is around community. It’s about what happens to a community when it’s under siege from a powerful force that is colonialism. I think loneliness is a real thing that afflicts the man that is Marechera. I think that contradiction, that tension that exists between his loneliness and the communal aspects of his work assumes a personality of its own.

Marechera himself says, “If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you.” He refused nationality and national identity in and insisted he belonged to a community of writers. And I think partially his alienation with Harare comes in him not finding a community of thinkers, an intellectual community that understands what he is trying to. And so at the end of the day he ends up identifying with the Beat Generation. The journal section in Mindblast echoes so many of the statements from the Beat Generation – Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac. I think he was lonely. And I think Mindblast was a cry of loneliness. So he is back in this community, he wants to identify with the community but the community shuts him out. But at the same time all his work – House of Hunger is about a community, in as much as there’s alienation, there’s loneliness, but the story is around community. It’s about what happens to a community when it’s under siege from a powerful force that is colonialism. I think loneliness is a real thing that afflicts the man that is Marechera. I think that contradiction, that tension that exists between his loneliness and the communal aspects of his work assumes a personality of its own.

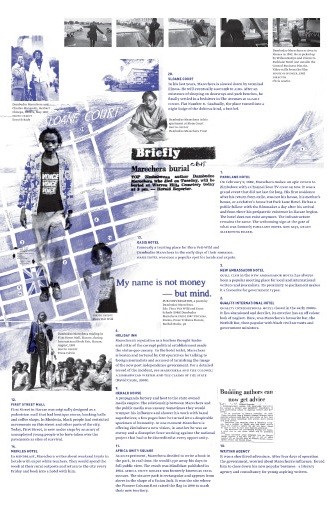

Initially, he was part of the community. Most of the writers in the early 80s were all in exile. These were all writers who had come back to Zimbabwe. He would fraternise with them. He actually ran for the Secretary General of the Zimbabwe Writers’ Union and lost by four votes. The only reason he lost was because people were afraid of his independence and they just didn’t want to antagonise the political system. Once he lost that position, once people decided to remove themselves from his ideas, I think that is where the rift with the community happens. That’s where he decides to start a writing agency – which is actually very popular. It gets fabulous press in all the newspapers in Zimbabwe for the four days that he runs it. For those four days there were long queues of young writers, of curious young people… you have to remember t his is four years after independence so there are all these people with questions, there are all these stories. There was a lot of dislocation, people have come back into the country, a lot of trauma, war trauma, so everyone has a story and they just didn’t know how to share the stories. And Marechera decided to be the story doctor. Apparently his office – which also has kind of a mythical quality to it – had no furniture; it was just carpeted with a phone in the corner. Everyone would come in and sit, so he was almost like a monk, like a spiritual master. He decide to build it outside the official institutions. And I think he understood the hunger, he understood… that’s why his legacy endures.

his is four years after independence so there are all these people with questions, there are all these stories. There was a lot of dislocation, people have come back into the country, a lot of trauma, war trauma, so everyone has a story and they just didn’t know how to share the stories. And Marechera decided to be the story doctor. Apparently his office – which also has kind of a mythical quality to it – had no furniture; it was just carpeted with a phone in the corner. Everyone would come in and sit, so he was almost like a monk, like a spiritual master. He decide to build it outside the official institutions. And I think he understood the hunger, he understood… that’s why his legacy endures.

His ghost still exists largely because of House of Hunger. It has assumed this prophetic power in the imagination of young people. It’s as if it he’d already foretold all the things that have happened and are happening in and to Zimbabwe. So, as a result, in 2005 the House of Hunger Poetry Slam was established. This became a platform for young, radical poets to come together. It happened at the Book Cafe but in this space you could say anything. It became a space of freedom that evaded censorship. Yes, there were rumours that state security were in the audience. But nothing ever got stopped. No one was arrested. And in a way a lot of this writing was almost addressed to Marechera because a lot of these young poets were borrowing from Marechera, were referencing specific things to

Marechera. Comrade Fatso did his album, House of Hunger. So a lot of work has been derived from Marechera.

[bandcamp width=100% height=42 album=2813839540 size=small bgcol=333333 linkcol=0f91ff]

I think in a lot of ways if Marechera had not existed we would have invented him. Our generation needed Marechera, needed something, someone who would help us shatter the monolithic way of looking at ourselves that Zanu PF has enforced.

Then & Now

It’s also a map of Harare both then and now. So the way in which Harare changes and the way in which Harare doesn’t change. I don’t think Matrechera would recognise Harare today and I don’t think there would be space for him. I think this new city has so many competing voices, so many things that are happening that Marechera would just become another marginal figure. So unless you were interested in him as a person and in his writings you wouldn’t seek him. But I don’t think he’d occupy the position that he had in the 80s. I was born in Harare and I left when I was 16 and ever since my relationship with Harare has been on and off. I feel that every time I leave and I come back. I can notice the changes but I can also see the sameness. The streets are the same but maybe the vendors have moved. The city is under siege from a generation that has no jobs, so they kind of decided to take over the city. So in this city, what would Marechera place be?

It’s also a map of Harare both then and now. So the way in which Harare changes and the way in which Harare doesn’t change. I don’t think Matrechera would recognise Harare today and I don’t think there would be space for him. I think this new city has so many competing voices, so many things that are happening that Marechera would just become another marginal figure. So unless you were interested in him as a person and in his writings you wouldn’t seek him. But I don’t think he’d occupy the position that he had in the 80s. I was born in Harare and I left when I was 16 and ever since my relationship with Harare has been on and off. I feel that every time I leave and I come back. I can notice the changes but I can also see the sameness. The streets are the same but maybe the vendors have moved. The city is under siege from a generation that has no jobs, so they kind of decided to take over the city. So in this city, what would Marechera place be?

The Basement

You would probably still find him in a bar. I think the bar is pretty much where things will be happening. African Unity Square has just lost its character. I think the riot police were always there. But there was a bar where I used to work which was a basement. The basement was like a city under the city, an underground, but also a city in a city. It was actually called The Basement. And then under the basement you’d find this club, there was an eatery, there was a studio… so it was like this artistic community. It was popular with rastas and all these kind of marginal, radical characters in the city. I’d probably point you to The Basement and say you’d find Marechera sitting next to the guys playing pool!

The full map of “Home Means Nothing to Me,” is available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.