By Roberto Alajmo

Background:

The ship Mendelsshon—referring to an NGO, and having on board 20 crew and 155 migrants rescued offshore Malta—has been drifting in the Straits of Sicily and the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas for 12 days in its quest for a landing place; an odyssey caused by prohibitions and proclamations of the Italian government that came to a conclusion in Palermo’s port, where landing and disembarking were at last authorised.

Situation:

On the dock, everything is ready to welcome the shipwrecked people. Twelve ambulances, throngs of healthcare professionals, cultural mediators, police officers, journalists, photographers, cameramen, and about ten additional characters who are difficult to label. As well as the authorized personnel, there is a small crowd of curious onlookers and/or layabouts, kept at a distance by a set of barriers and by the watchful eye police. Many hold their mobile phones and want to make sure they work properly, in order to take some pictures or shoot a video.

In a preeminent position, surrounded by a ring of collaborators first, and then another ring of journalists and photographers, stands the mayor Leoluca Orlando wearing a mayoral sash displaying the Italian flag, a detail that emphasises the official character of his presence. It is not the first time Orlando stands on the dock to highlight his personal commitment and the whole City of Palermo’s efforts in welcoming migrants.

Some minutes prior, some operators wearing white overalls and gauze masks boarded the ship Mendelsshon. Now, the first of them is back on the steps of the ladder, and is immediately followed by a second one. Each one of them accompanies a black person wrapped in a golden thermal blanket. They begin descending.

The attack:

Orlando take two steps forward, preparing to welcome the migrants. In such circumstances he usually does not deliver a public speech, but shakes the hands of each new-comer, one by one. He is about to do that, and everybody is expecting that: a simple gesture conveying a strong meaning.

But this time, things are different.

First, a buzz is heard. Then, a woman screams.

Everyone turns around in an attempt to understand what is happening.

It happens: a guy, an ordinary guy, of average age, average build and average crazed expression has avoided police detection and climbed over the barriers.

Now he is face to face with the mayor. A hostile face-to-face confrontation, but not too hostile if we consider only the looks they give each other. However, the guy is holding a big gun in his hand. That gun changes everything.

Two shots are fired in rapid succession. Orlando’s Twitter consultant is the first to realise what is going on. His response is straight out of an action movie, he uses his body to shield his Chief. But he’s too quick off the mark, before the gun actually fires. As a result, he is on the ground the very moment the bullets plunge into the mayor’s chest. The mayor stumbles, his collaborators try to support him but they are only able to accompany his body falling to the ground.

One hour later:

News about the murder of Mayor Orlando spreads around the city, the country and the world.

The New York Times online edition, just thirty minutes later, declares: “

PRO-IMMMIGRANT MAYOR KILLED IN PALERMO”.

The people of Palermo are dismayed, touched, they cannot believe it. Everyone looks for news on the web, but the reporting is always the same. The killer, who was immediately arrested, is found to be a degenerate, a former militant of a xenophobic, extreme-right movement, from which he was expelled some months earlier due to repeated and disorderly intoxication.

Within a few hours, two rallies are organised: one at the port and another in front of the Town Hall. The respective organisers represent two incompatible factions within public opinion, both attributable to the left wing. The rally at the port is dispersed by police, who are also leading the investigation and have restricted access to the crime scene. So, the port demonstrators have decided to join the other rally (initially criticised as reformist), and the crowds are massive. When the gathering is at its peak, a huge picture of smiling Orlando is displayed from the central balcony of Palazzo delle Aquile, the Town Hall. Many people cannot hold their tears.

Two days later:

The funeral draws thousands, starting from Orlando’s home and passing through the whole city up to reach San Domenico square. It is an extraordinarily long procession, held by will of his family to allow the entire city to say goodbye to the mayor who left his personal mark on Palermo more than any other, by making it the most welcoming capital in the Mediterranean area. The body is buried in the church of San Domenico, the city’s pantheon where, for years, someone would leave a small bunch of field flowers at least once a week.

The same day, during an expressly called meeting of the Council of Ministers, the Italian government denies its inflexible course of action in the matter of immigration and allocates €20 million to support reception and promote the integration of refugees. This set of norms is named after the late mayor.

Two months later:

In the light of some recent limitations allegedly imposed by the European Union, a new Council of Ministers reviews the so-called “Orlando Package”, reneging on €19.5 of the €20 million; but it drafts, in exchange, a programme of lectures and meetings in schools at all levels. Goal: to spread the culture of true tolerance among the younger generations. On this occasion, the government spokesperson invents a slogan that is reported by every newspaper: “Tolerable Tolerance”, meaning Italy must aspire to a tolerable level of tolerance.

Investigations on the murder continue, focusing on the killer. There seem to be no instigators: the guy was drunk and out of control from a psychological point of view; he was in legal possession of the gun. Besides the official investigation, there are uncontrolled rumors that the assassination was motivated by personal hatred not politics—despite what appears to be overwhelming public opinion on the motive. At the beginning, this theory seems some harmless bullshit. But, in the weeks following two radically opposing positions arise: those who believe it is no bullshit and those who think it is not harmless.

One year later:

On the anniversary of the Good Mayor’s (nowadays Orlando’s nickname) assassination, during a simple ceremony at the crime scene, the new mayor, who belongs to the political party La Lega (The League) and was elected only about four months earlier, chooses some touching words to commemorate the martyrdom of his predecessor, talking about him with great respect, despite their differing political views, and condemning violence of all kind. He makes only a brief mention about the circumstances and motives behind the murder, still considered confidential information held by the Judiciary that has taken charge of the investigation.

Despite the anesthetising effect of public ceremonies, generally speaking, the memory of that assassination stays alive. During his life Orlando provoked strong and opposing opinions, but the passing of time has laid a veil of almost unanimous respect, affection in some cases. Even his boldest opponents in politics recognise his role in changing Palermo, and the way Palermo is perceived in the world.

His political legacy is a whole different story. The center-left wing, despite being more or less united, is not able to find an appropriate candidate to replace his predecessor, and during the following municipal elections was easily defeated by the solid front grouping the xenophobic right-wing movements and their conniving mates. The actual weakness of the city’s progressive groups is made worse by the spirit of current times, influenced by simplifications spread by populists.

Ten years later:

The spirit of times remains the same. People still talk about the many positive things that the Good Mayor did, but in the meantime, people keep electing Awful Mayors.

However, it would be unfair to say that there is no news.

For reasons that are difficult to explain, in this 10-year glaciation, many associations, movements and clubs are still active in Palermo, and have preserved the seeds of welcoming.

Also ideally speaking, each of these associations put these seeds aside, wrapped them in a cloth and put them away for safekeeping at the bottom of a drawer. History spins around in a bizarre way, it seems, and suddenly all these associations, movements, clubs, and single individuals too, open that drawer at (almost) the same time, take the cloth holding the seeds and metaphorically plant them. They plant them metaphorically, and they metaphorically wait.

Fifteen years later:

Just at a time when all hope seems long lost, something begins to happen in Palermo. It looks like that the soil was still fertile and the seeds have germinated. After being on the verge of extinction, a great number of small associations have finally started to streamline their efforts, dismissing divisions and marching steadily in one common direction. Things begin happening in town—rallies, concerts, performances, seminars—all produced with little or no money. But the best among Palermo’s citizens are like cactuses, they don’t need to be watered.

Palermo’s associations present their own candidate at municipal elections. His name is Orlando Lucchese, a 30-year old whose mother is from Senegal and whose father is a street-food seller in the working-class district of Albergheria. Through enormous sacrifices, his parents send him to study in Paris. He comes back to Palermo expressly to run as the mayor. According to initial predictions, he does not have a chance. He knows just a few people, he owes no favours to anyone, he answers to no one, but making these his strong points, he surprisingly wins, and defeats his opponent, a lawyer nominated by the right-wing under the predictable slogan: “Italians first”.

An interview with the new mayor appears in the main local newspaper, titled “History does not stop”, in which Lucchese, among other things, recalls an incident that occurred when he was a teenager. He was at the port on the same day the Mayor Orlando was murdered. He had gone to hang around there with some friends, had seen the crowd of people and got near the barriers to take a closer look. The newly-elected mayor affirms that only seconds before the shots that killed Orlando were fired, he had exchanged glances with the mayor, and with that glance Orlando had sort of said hello to him.

He calls it that: “Sort of said hello”.

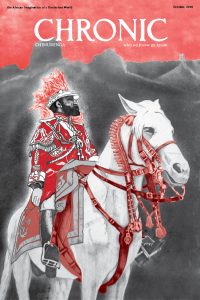

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

This and other stories and maps are available in the new issue of the Chronic, On Circulations And The African Imagination Of A Borderless World, which maps the African imagination of a borderless world: non-universal universalisms, the right to opacity, refusing that which has been refused to you, and “keeping it moving”.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurengashop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button][button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/subscribe” color=”red”]Subscribe[/button]