“…The struggle of black people inevitably appear in an intensely cultural form because the social formation in which their distinct political traditions are now manifest has constructed the arena of politics on ground overshadowed by centuries of metropolitan capitalist development, thereby denying them recognition as legitimate politics. Blacks conduct a class struggle in and through race. The BC of race and class cannot be empirically separated, the class character of black struggles is not a result of the fact that blacks are predominantly proletarian, thought this is true…”- (Frank Talk Staff Writers in ‘Azania Salutes Tosh’ – circa 1981)

front cover:

Tosh by Steve Gordon

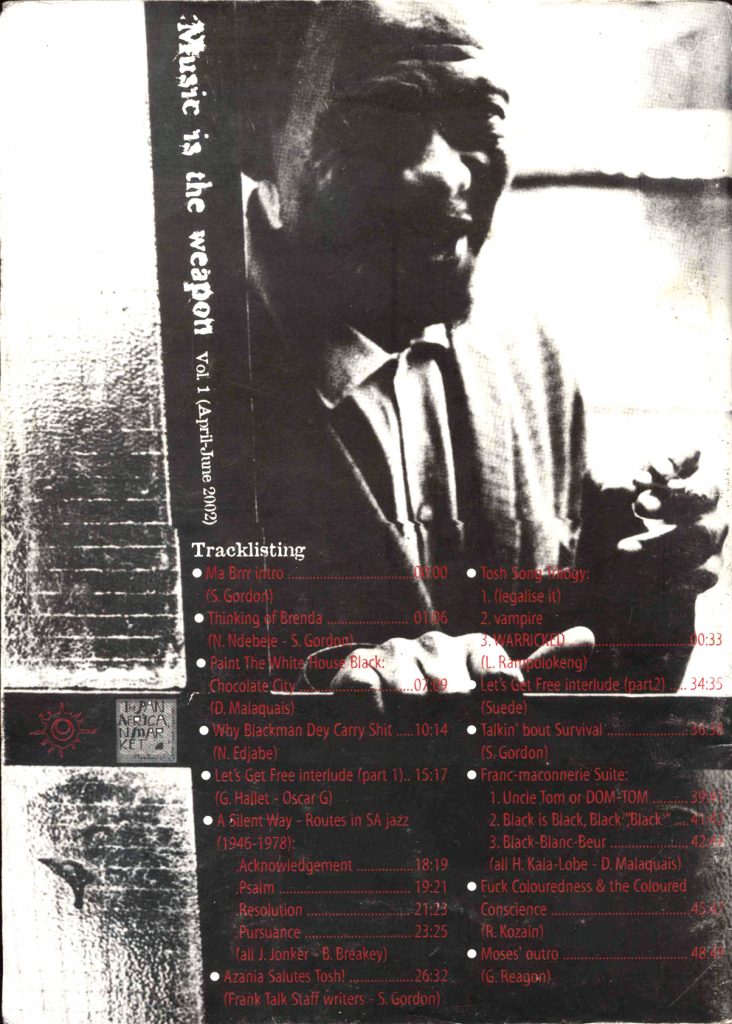

back cover:

Kippie by Basil Breakey

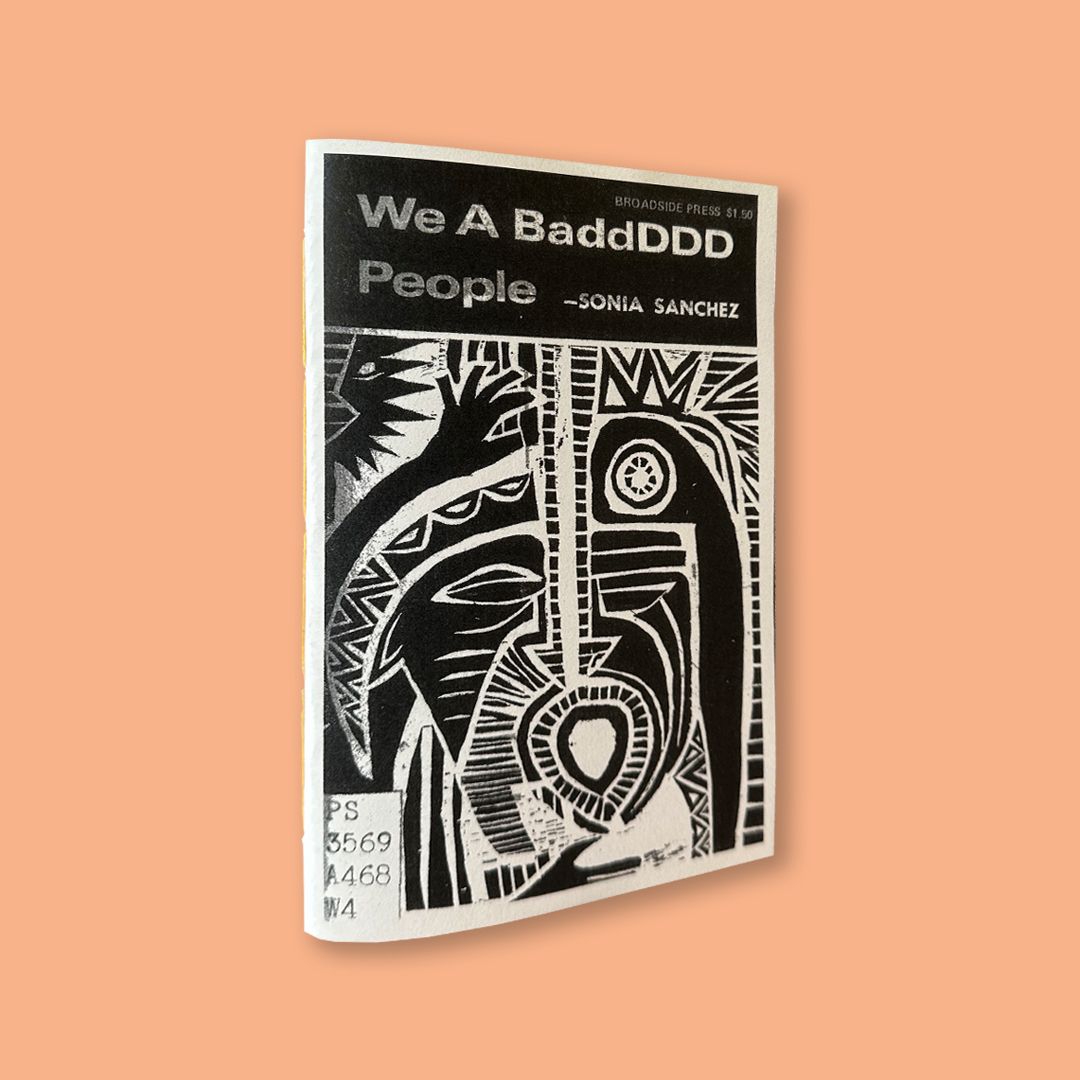

We A BaddDDD People by Sonia Sanchez (Broadside Press, 1970)

We A BaddDDD People by Sonia Sanchez (Broadside Press, 1970)

Sonia Sanchez's second book of poems (Broadside Press, 1970), similar to Homecoming (1969) in experimental form and revolutionary spirit, is dedicated to “blk/wooomen: the only queens of this universe” and exemplifies the poetics of the Black Arts movement and the principles of the black aesthetic. It depicts the experiences of common black folk in courtrooms, slum bars, and on the streets, with pimps and jivers, boogalooing and loving Malcolm X. It celebrates the majestic beauty of blackness and speaks of revolution in the language of the urban black vernacular. Rhythms deriving from the jazz and blues of John Coltrane and Billie Holiday create a poetry of performance in which the audience participates vigorously in meaning-making. Experimental in style, it is antilyrical free verse, using spacing, slash marks, and typography as guides to performance.

Characterizing Sanchez as a genuine revolutionary whose “blackness” is not for sale, Dudley Randall's introduction leads into the first of three sections, “Survival Poems,” which approach survival from political and personal perspectives. Some show how “wite” practices imperil black people's survival, seducing by heroin, marijuana, and wine or by exploding dreams. Others show how blacks undermine their own survival: the “makeshift manhood” underlying sexual neediness in “for/my/father,” the willful blindness of black “puritans,” and the hypocrisy of pseudorevolutionaries whose rhetoric masks self-indulgence. Personal poems recording moments of near-hysteria, depression, and longing lead to the revolutionary vision of “indianapolis/summer,” proposing communal love as a necessary prelude to real change.